The tax proposals in the budget that the House approved on April 15 place a top priority on cutting taxes for high-income people, while doing nothing to reduce budget deficits, themselves. [1] In addition to making the Bush tax cuts permanent and continuing to provide relief from the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) at a cost of nearly $4 trillion over ten years, the House budget advances a series of additional tax cuts that would primarily benefit high-income households at a cost of nearly $3 trillion over that period, most of which is assumed to be offset by reductions in tax expenditures that are left unspecified. [2]

The House budget would permanently lock in all of the Bush tax cuts, which flow disproportionately to high-income people. It also would make permanent the relief from the AMT that now is regularly extended every year or two. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that extending these tax cuts would cost $3.8 trillion over the coming decade, the vast majority of which would be attributable to the Bush tax cuts. [3] The House budget essentially would finance these tax cuts with extremely large budget cuts, including cuts in a number of key programs for people with low or moderate incomes. [4]

The House budget also calls for tax reform. But its few specific proposals in this area — reducing the top individual and corporate rates to 25 percent and eliminating the AMT altogether [5] — along with its proposal to rescind the health reform law’s Medicare payroll tax increase on high-income people — follow a familiar pattern and have two common characteristics: they are very costly and would disproportionately or exclusively benefit people with high incomes.

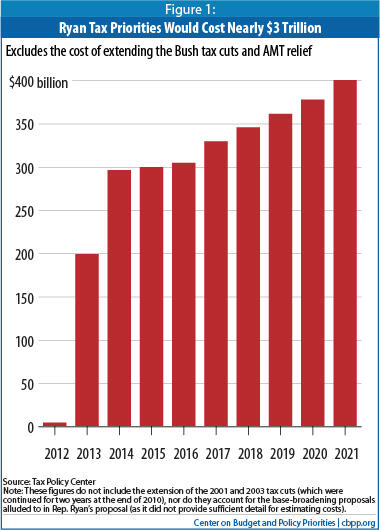

The Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center (TPC) estimates that the Ryan budget’s specific tax proposals (other than the proposal to make the Bush-era tax cuts and AMT relief permanent) would cost $2.9 trillion over the next ten years (see Table 1). This cost would be on top of the $3.8 trillion cost of making the Bush tax cuts permanent. Roberton Williams of TPC has noted that, “[v]irtually all of the tax savings from [these additional proposals] would go to households making upwards of $200,000 — the 5 percent of tax units who currently face marginal rates over 25 percent.”[6]

The House budget plan assumes that $2.5 trillion of this $2.9 trillion in additional tax cuts (presumably the tax cuts other than the measure to repeal the increases in the Medicare payroll tax for high-income households) would be paid for by broadening the tax base through changes in tax expenditures. But the base-broadening measures are left entirely unspecified.

In addition, as TPC’s Williams has explained, even if the House were to follow through on the commitment to offset $2.5

trillion of these costs, the net result would be “very likely to make the tax code much more regressive than it is today.”

[7] Measures to lower the top rates to 25 percent, abolish the AMT, and repeal the health reform law’s payroll tax increase on people with incomes over $250,000 are tilted heavily toward the most affluent households. It is difficult to imagine a politically plausible series of tax expenditure reforms that would not only raise enough money to offset most of these new costs but also would raise so much of that money from high-income households that the overall result wouldn’t be regressive.

[8] For example, eliminating one of the largest tax expenditures, the exclusion of employer-provided health care from taxable income, would reduce after-tax incomes by about 2 percent, on average, for households in the middle fifth of the income distribution but by one-quarter of 1 percent for households in the top 1 percent of the income distribution. The combination of reducing the top rate to 25 percent and shrinking tax expenditures would likely benefit people at the top of the income scale at other Americans’ expense.

Moreover, from a fiscal policy standpoint, using the savings from curbing inefficient tax subsidies to finance even bigger upper-income tax cuts, rather than to do more to address the nation’s fiscal problems, would represent misguided priorities.

Table 1:

Tax-Cut Priorities in House Budget Would Cost Nearly $3 Trillion Over Next Ten Years — Not Including Cost of Extending Current Tax Cuts |

| Provision | Cost Over 2012-2021 |

| Reduce top corporate tax rate to 25 percent | $900 billion |

| Repeal individual AMT* | $500 billion |

| Reduce top income tax rate to 25 percent** | $1,100 billion |

Repeal Hospital Insurance (Medicare) surtaxes on income over $250,000

($200,000 for single filers)*** | $400 billion |

| Total | $2.9 trillion |

* This is the cost of repealing the AMT, over and above the cost of making current AMT relief permanent.

** For its estimate, TPC assumes that the current 25 percent bracket is combined with all of the brackets above it, creating one much larger 25 percent bracket.

*** This includes a 3.8 percent surtax on investment income, and a 0.9 percent tax on wages, that exceed $250,000 ($200,000 for single filers). Both provisions were enacted as part of health reform.

Note: The House budget proposes to offset approximately $2.5 trillion of these tax cuts with unspecified reductions in tax expenditures, bringing the net cost of all of its tax proposals (including the extension of the Bush tax cuts and AMT patch) to about $4.2 trillion. |

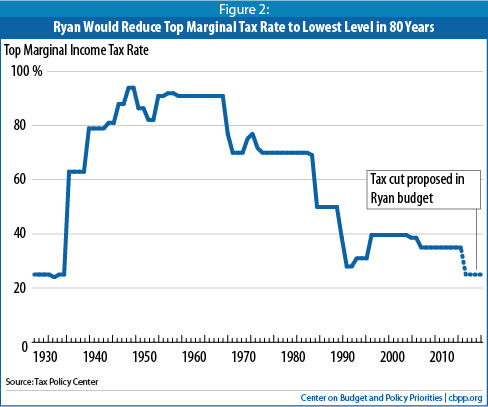

The costliest of the new tax cuts in the House budget would shrink the top individual tax rate to 25 percent, its lowest level since before the New Deal (see Figure 2). TPC estimates that eliminating the tax brackets above 25 percent would cost $1.1 trillion over ten years. (This would be in addition to the $700 billion cost of extending the Bush tax cuts for those in the top brackets.)

Reducing the top income tax rate to 25 percent would primarily benefit households with the highest incomes. For example, a family with two children and an income of $1 million (of which we assumed $850,000 comes from earnings) would receive an annual tax cut of $51,000 from lowering the top rate to 25 percent, which would be in addition to the $64,000 the family would get from extending all of the Bush tax cuts. And family with an income of $10 million (and $8.5 million in earnings) would receive a tax cut of $730,000 a year from the reduction in the top rate.

In contrast, 95 percent of Americans would receive no benefit at all from lowering the top rate to 25 percent, because they would already be in the 25 percent tax bracket or a lower bracket (assuming that the Bush tax cuts were extended, as the House budget envisions). [9]

The House budget also would cut the corporate tax rate to 25 percent at a cost of more than $900 billion over the next decade. The budget does not indicate what corporate or other tax expenditures might be narrowed or eliminated to offset this cost. Corporate tax revenues have already declined markedly in recent decades as a share of the economy. [10]

Finally, TPC has estimated that repealing the Medicare payroll tax changes in the health reform law would cost nearly $400 billion over ten years. All of the benefit from repealing these measures would flow to high-income people. People who make over $1 million a year would receive an average annual tax reduction of $46,000 just from this repeal provision.

The proposal in the House budget plan to devote every dollar of revenue raised by curbing tax expenditures to finance other tax cuts — principally the lowering of the top rate to 25 percent — suggests that the plan’s framers regard additional tax cuts for high-income individuals as a higher national priority than stronger deficit reduction. Their proposal also ignores the fact that incomes have skyrocketed at the top of the income scale even as the real income of the typical American household has fallen over the last decade.

In the face of both the nation’s serious long-term fiscal problems and the trend toward greater income inequality, these proposals would be highly regressive and raise substantially less revenue. That is hardly the direction in which national policy ought to move.