The Social Security proposal from the co-chairs of President Obama’s fiscal commission is not a suitable starting point, let alone a reasonable outcome, for Social Security reform because it relies far too much on deep benefit cuts to restore solvency to the program and makes a number of harmful changes.

The Social Security proposal that the co-chairs — former Clinton White House Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles and former Republican Senator Alan Simpson — included in their overall plan[1] to reduce long-term budget deficits would generate nearly two-thirds of its Social Security savings over 75 years — and four-fifths of its savings in the 75 th year — from benefit cuts (as opposed to revenue increases). It would cut benefits for the vast majority of Social Security recipients, weaken the link between a recipient’s benefits and past earnings (which could undermine public support for the program), and, despite the claims of the co-chairs, fail to protect most low-income workers from benefit cuts. Most Social Security recipients would be further squeezed by the higher out-of-pocket costs that Bowles-Simpson proposes for those on Medicare.

The Bowles-Simpson budget plan did not receive support from enough members of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform to be issued as a final report.[2] Nevertheless, the co-chairs and several Senators have suggested that it serve as the “starting point” for a national debate on how to reduce projected deficits. Its recommendations for Social Security, however, are quite problematic.

Social Security is the federal government’s biggest domestic program, paying benefits to about one in six Americans and 90 percent of elderly Americans.[3] The program is in solid financial shape in the near term, able to pay scheduled benefits without difficulty until 2037 and about three-fourths of promised benefits even after that.

But Social Security does face a long-term challenge. [4] Policymakers will have to restore the program’s “solvency,” meaning that its income and expenditures need to be brought into balance over the next 75 years and beyond. In doing so, policymakers should act sooner rather than later so that they can phase in the required benefit and tax changes gradually, giving today’s workers plenty of time to adjust their plans for work, saving, and retirement. The Bowles-Simpson proposal for Social Security, however, is not an appropriate starting point.

Although a plan to restore Social Security solvency will likely require both benefit cuts and tax increases, policymakers have limited room to cut benefits without causing hardship for many seniors and people with disabilities. [5]

- The average Social Security benefit is only about $1,100 a month, or $14,000 a year. That’s less than 30 percent above the poverty line. Some 95 percent of retired workers — and even larger percentages of disabled workers and aged widows — receive monthly benefits of less than $2,000.

- Most beneficiaries have little significant income from other sources . On average, Social Security provides nearly two-thirds of income for beneficiaries age 65 and older. In 2008, the typical (or median) elderly beneficiary had a total household income of only about $20,000 a year, most of it from Social Security.

- Most beneficiaries will lack other pension benefits. Coverage under employer-provided defined-benefit pension plans has fallen precipitously in recent years. As a result, for most seniors Social Security will be the only guaranteed retirement income they have that does not depend on the vagaries of the stock market, and that provides full protection against inflation for the rest of their lives.

- Social Security benefits in the United States are low compared with those in other advanced countries. The average member country of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development has a public pension program whose benefits replace about 61 percent of prior earnings for the median (or typical) worker. The U.S. system is far less generous (as the next bullet indicates), ranking 26 th out of the 30 OECD nations.

- Future retirees already are slated to receive lower benefits, relative to their past earnings, due to increases in the Social Security retirement age and escalating Medicare premiums . For a medium worker (earning about $43,000 in 2010 dollars) who retires at age 65 today, Social Security replaces only about 37 percent of previous earnings, after subtracting Medicare premiums [6]. That figure will fall further as the program’s age for full benefits (often called the “normal” or “full” retirement age), which has climbed from 65 to 66 over the past decade, rises gradually to 67, due to a benefit reduction that Congress enacted in 1983, and as Medicare premiums take a bigger bite. By 2030, that retiree’s check will replace just 32 percent of past earnings, after subtracting Medicare premiums.

These facts argue for limiting any cuts in future Social Security benefits.

Bowles-Simpson includes a variety of Social Security benefit cuts but only one measure to raise Social Security taxes, illustrating its lack of balance. It would cut Social Security benefits in three ways:

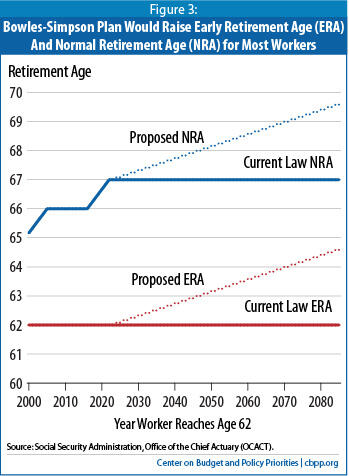

- Increasing the Retirement Age . The full retirement age, which used to be 65, is now 66 and will gradually rise to 67 by 2022 for people born in 1960 and later. Retirees may claim reduced Social Security benefits starting at age 62 (the “early eligibility age”). Under the co-chairs’ plan, the full retirement age would continue rising after 2022 (in accordance with changes in average life expectancy) and the “early-retirement age” would rise by the same amount, with certain “hardship” exemptions as described below. Sometime before 2050, the early eligibility age would reach 63 for most workers and the full retirement age would reach 68. By about 2070, the early eligibility age would reach 64 and the full retirement age would reach 69. Contrary to a widespread misimpression, any increase in the full retirement age amounts to an across-the-board cut in benefits for all retirees regardless of the age at which they file — including people who do not retire until 67 or even 70 — as explained in Box 1.[7]

- Changing the Benefit Formula . Changes in the basic benefit formula would further reduce benefits. While these benefit cuts would be largest for workers with above-average earnings, they would affect the vast majority of retired and disabled workers. The co-chairs would soften the impact on some low earners by adding a new, enhanced minimum benefit equal to 125 percent of the federal poverty level. But the proposed minimum benefit is clumsily designed — few low-paid workers actually would qualify for it, as explained below. As a result, even many very low-income workers would face benefit cuts.

The full retirement age is 66 and will rise to 67 for people born in 1960 and later. Raising the retirement age amounts to an across-the-board cut in benefits, regardless of whether a worker files for Social Security before, upon, or after reaching the full retirement age. A one-year increase in the full retirement age is equivalent to a roughly 7 percent cut in monthly benefits for all retirees who are affected.

The full retirement age really just means the age at which full benefits are paid.a Workers can file sooner and collect permanently-reduced monthly benefits, or they can file later and get larger monthly benefits. Shifting the retirement age means the early retiree gets a deeper reduction and the delayed retiree gets a smaller bonus.

When the full retirement age was 65, a worker who filed at 62 — as about half of claimants do — could get 80 percent of a full benefit (or $800, if his or her full monthly benefit were $1,000). Now that the full retirement age is 66, a worker who files at 62 gets 75 percent of a full benefit ($750, in this example); when the full retirement age rises to 67, a worker who files at 62 will get just 70 percent of a full benefit (or $700). That reduction in monthly benefits lasts for the rest of his or her life.

At the other extreme, someone who waits until 70 to file now gets nearly a one-third bonus — or $1,320, assuming that his or her full benefit is $1,000. When the full retirement age rises to 67, the bonus will shrink to about one-quarter — the worker in our example will receive $1,240. In short, an increase in the retirement age reduces benefits across the board.

The Bowles-Simpson proposal would deepen these reductions. By around 2070, the full retirement age would be 69 and the earliest age of eligibility (except for the minority who qualify for a “hardship exemption”) would be 64. For someone reaching 62 in that year whose full retirement age would otherwise be 67 under current law, that translates into a benefit reduction of about 14 percent.

| Raising the Full Retirement Age Reduces Benefits for Everyone |

| Illustrative monthly benefit, if claimed at age: | Under Current Law, when full retirement age is: | Under Bowles-Simpson, when full retirement age is: |

| 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 |

| 62 | $800 | $750 | $700 | * | * | * |

| 63 | 867 | 800 | 750 | 700 | * | * |

| 64 | 933 | 867 | 800 | 750 | 700 | * |

| 65 | 1,000 | 933 | 867 | 800 | 750 | 700 |

| 66 | 1,080 | 1,000 | 933 | 867 | 800 | 750 |

| 67 | 1,160 | 1,080 | 1,000 | 933 | 867 | 800 |

| 68 | 1,240 | 1,160 | 1,080 | 1,000 | 933 | 867 |

| 69 | 1,320 | 1,240 | 1,160 | 1,080 | 1,000 | 933 |

| 70 | 1,400 | 1,320 | 1,240 | 1,160 | 1,080 | 1,000 |

| Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Estimates assume a Primary Insurance Amount, or full benefit, of $1,000 a month and an increase in the monthly benefit of 8 percent for each year that an individual delays drawing benefits beyond the full retirement age. The full retirement age has risen from 65 to 66 — and will gradually climb further, from 66 to 67, for people who turn 62 in 2017 through 2022. The Bowles-Simpson proposal would continue to raise the full retirement age, after 2022, in step with life expectancy — by about one month every two years — and would set the early eligibility age (currently 62) at the full retirement age minus five years. |

a. The only other major significance of the full retirement age is that the Social Security earnings test no longer applies. Early retirees now generally give up $1 of benefits for each $2 by which their annual earnings exceed $14,160. After age 66, this offset ceases to apply. - Reducing Cost-of-Living Adjustments . Cost-of-living adjustments would fall by about 0.3 percentage points a year under the proposal to adopt a different measure of inflation — the chained Consumer Price Index (CPI) — which analysts generally regard as a more accurate measure of inflation for the economy as a whole. This change would start in December 2011 and would affect everyone on the benefit rolls at that time. Softening the impact of this COLA change would be a benefit increase for people who have been eligible for Social Security benefits for 20 years or more, culminating in an average 5-percent benefit bonus after 24 years of eligibility.[8]

The co-chairs’ proposal contains only one provision that would directly raise revenues. It would gradually increase the maximum amount of a worker’s earnings that are subject to the Social Security payroll tax (an amount that now stands at $106,800) so that 90 percent of all earnings would be taxable, as Congress intended in the 1977 Amendments. (Currently, about 85 percent of earnings in covered employment are taxable, a figure that is expected to slip to 83 percent in coming years.) This provision would be phased in extremely slowly; the Social Security actuaries estimate that the 90-percent target would not be reached until around 2050.

Finally, Bowles-Simpson would cover all newly-hired state and local workers under Social Security. About 30 percent of state and local government workers are now outside the Social Security system, although many of them eventually qualify for Social Security based on other employment. This proposal is sound and meritorious but has fairly small effects on the program’s solvency; it would generate more tax revenue in the years after it was implemented, but would eventually boost Social Security benefit payments by about the same amount.

The Social Security actuaries judge that Bowles-Simpson would make the combined Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance trust funds (i.e., the Social Security trust funds) solvent.[9] It would trim the program’s deficit by 2.15 percent of taxable payroll over the next 75 years, and by 4.2 percent of taxable payroll in the 75th year, excluding the effects on the funds’ interest income. (See Table 1.)

Table 1:

Social Security Provisions of the Bowles-Simpson Plan

(Effect on Actuarial Balance, as a Percent of Taxable Payroll) |

| Provision | Effect over 75 years | Effect in 75th year |

| Raise retirement age | 0.34% | 1.22% |

| Reduce PIA formula | 0.86 | 2.12 |

| Enhance minimum benefit | -0.15 | -0.26 |

| Use chained CPI for COLAs | 0.50 | 0.70 |

| Boost benefits after 20-24 years of eligibility | -0.15 | -0.23 |

| Increase taxable maximum | 0.67 | 0.90 |

| Cover new state and local employees | 0.16 | -0.12 |

| Interactions | -0.08 | -0.13 |

| Total | 2.15% | 4.20% |

| Source: Social Security Administration, Office of the Chief Actuary (OCACT). A positive sign indicates that the provision improves the program’s actuarial balance; a negative sign indicates that it increases the program’s deficit. |

The lion’s share of those savings comes from benefit cuts. The benefit provisions account for nearly two-thirds of the savings over the 75-year period and four-fifths of the savings in the 75th year. [10]

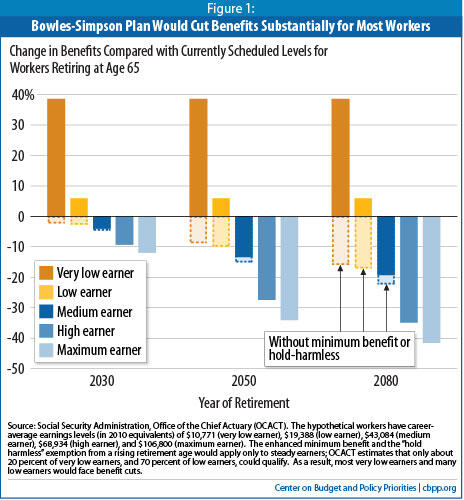

Due to these changes, all beneficiaries — except a very few with low earnings throughout a long career — would face losses in benefits (see Figure 1). The benefit of a medium earner (earning about $43,000 in today’s terms) would fall by 13 percent below the currently scheduled amount in 2050 and by 19 percent in 2080.

The typical beneficiary could not easily absorb such reductions. As noted earlier, Social Security benefits are modest. That lifelong medium earner retiring at 65 in 2010 receives a benefit of just $1,397 a month ($16,764 a year) — which is only about 55 percent above the poverty line and little more than what researchers view as a “no-frills, bare-bones” budget for retirees. [11] The typical retiree does not have significant income from other sources.

The actuaries estimate that, despite the rapid aging of the population, Bowles-Simpson would hold Social Security outlays to just 5.1 percent of GDP in 2084. That’s barely above today’s level (4.8 percent of GDP), even though the age composition of the population will change drastically over that period. People 65 and older are expected to make up over 22 percent of the U.S. population by 2084, up from 13 percent today. Bowles’ and Simpson’s answer to an aging population is to hit benefits hard rather than pursue a balanced mix of policies.

Bowles-Simpson’s cuts in Medicaid and Medicare would pose further problems for millions of Social Security beneficiaries. They call for increasing the amounts that elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries must pay for health care services (presumably through higher co-payments) under both Medicare and the Medigap policies that supplement Medicare coverage while giving them better protection against catastrophic expenses.

The plan lacks details on how these changes would work, and they might well be reasonable parts of a balanced deficit-reduction plan — if they were not extracted from the same modest-income seniors and people with disabilities whose Social Security benefits were cut at the same time. A typical Medicare enrollee already spends 17 percent of his or her income on out-of-pocket health spending. [12] As Drew Altman, the highly respected president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, recently explained, “It will be difficult if not impossible to ask the majority of beneficiaries to pay more or make do with less… Warren Buffet is not the typical Medicare beneficiary. Instead the prototype is an older woman with multiple chronic illnesses living on an income of less than $25,000 who spends more than 15 percent of her income on health care. It is the people on these programs and the realities of their lives that have been left out of the discussion.” [13]

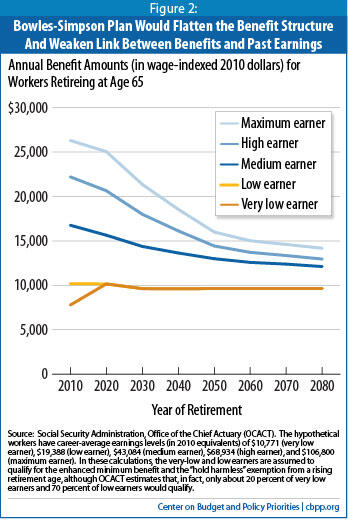

Bowles-Simpson would cut benefits for most workers, but especially those with average and higher earnings. The co-chairs term that a “progressive” feature of their plan. Yet one key consequence has received little attention:

the proposal would greatly weaken the link between benefits and past earnings.

All Social Security benefits are based on a worker’s lifetime earnings — technically, on his or her Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME). The program is progressive in that, while benefits are larger in dollar terms for higher earners, they represent a larger percentage of previous earnings for lower earners on the logic that lower earners will be less likely to have other pension coverage and less able to save. For example, under Social Security as it now stands:

- A low-paid worker who earned an average of about $19,000 a year (in 2010 terms) over his or her career and retires at age 65 in 2010 receives an initial retirement benefit of $10,200 a year, enough to replace 55 percent of his or her prior earnings. (That ratio is often dubbed the “replacement rate.”)

- A medium earner who had earnings averaging about $43,000 a year gets an annual benefit of about $16,800. While the benefit is higher than for the low-paid worker, the replacement rate is lower — only 41 percent of prior earnings. His or her earnings were about 2.2 times as high as those of a low-paid worker, but his or her benefits are 1.6 times as high.

- A very high earner — a worker who spent his or her entire career earning the maximum amount on which payroll taxes are levied, now $106,800 a year — gets a benefit of $26,300 a year. This individual had earnings subject to the payroll tax that were about 5.5 times as much as the low-paid worker’s earnings — and paid 5.5 times as much in taxes — but gets a benefit that is just 2.6 times as high.

Bowles-Simpson would weaken the link between earnings and benefits by targeting much sharper cuts at workers with above-average earnings than workers with low earnings. In the long run,

most workers would end up getting very similar benefits, despite having paid very different amounts in payroll taxes. (See Figure 2.)

By 2080, the counterpart of today’s very high earner — one who earns the equivalent of $106,800 (in 2010 terms) — would get a benefit only 1.5 times as big as the low earner, despite having paid about 5.5 times as much in taxes. That could undermine the program’s broad public support over time, and as a result, would risk jeopardizing Social Security’s most significant achievements, which include its universal coverage, its protection against death and disability, and its lack of means-testing.[14]

Bowles-Simpson would raise both the early and full (or “normal”) retirement age for most workers. Once the full retirement age reaches 67 under current law (for workers who reach age 62 in 2022), the co-chairs would keep raising it in step with increases in average life expectancy; consequently, the full retirement age would rise by about one month every two years. The early eligibility age, now 62, would rise in lockstep, always remaining five years below the full retirement age. (See Figure 3.) [15]

Each one-year increase in the full retirement age acts as roughly a 7-percent cut in benefits, regardless of the age at which the worker actually files. That’s true whether the worker files at earliest eligibility (when he or she can first collect a reduced benefit), at the full retirement age (when he or she can collect an unreduced, or regular benefit), or at age 70 (when his or her benefit, boosted by a credit that raises benefits for individuals who do not begin drawing them until after the normal retirement age, reaches its maximum amount).[16] (See Box 1.)

Early retirement is an important safety valve for many people who have a hard time continuing to work. Researchers tell us that a significant minority of people who file promptly for Social Security benefits at age 62 have serious health problems but do not qualify for disability insurance. [17] Even those in better health can face obstacles; older workers are less likely than younger workers to lose their jobs but, when they do, they have more difficulty finding a new one. [18] Social Security experts have wrestled with the issue of how to protect people who cannot keep working if policymakers raise the program’s full (or “normal”) retirement age, its early retirement age, or both. Unfortunately no one has yet devised a good answer. (See Box 2.)

Bowles-Simpson purports to address these concerns by including a “hardship exemption” for certain retirees. It would allow qualified workers to continue to claim benefits at age 62 as the early- and full-retirement ages increase, and exempt them from the larger monthly benefit reduction resulting from a higher retirement age. Yet the co-chairs failed to include any details on how such a “hardship exemption” would work. They proposed simply to direct the Social Security Administration (SSA) to “[design] a policy over the next ten years that best targets the population for whom an increased [early retirement age] poses a real hardship, [while] considering relevant factors such as the physical demands of labor and lifetime earnings in developing eligibility criteria.”[19] In short, they glossed over the difficulty of devising an equitable option that would be practical to administer — a task that has eluded experts for years.

Because they needed a basis to estimate the financial effects of this provision, SSA’s actuaries worked with the fiscal commission’s staff to hammer out illustrative details. Specifically, they assumed that people who had worked at least 25 years and had lifetime average earnings less than 250 percent of the poverty level would be exempt from the retirement-age increase. In 2010 terms, these would be people who earned at least $4,480 each year (the amount required for an individual to be credited with four “quarters of coverage” under Social Security) for 25 years, but whose earnings over their career averaged less than $25,700 a year. The exemption would be phased out for people with average earnings above this level and would disappear completely at earnings of 400 percent of the poverty level (average earnings of about $41,000). Everyone with less than 25 years of work, and everyone with average earnings over $41,000, would not qualify for the hardship exemption and, hence, would bear the full brunt of the retirement-age increase.

Americans are living longer, and advocates of raising the retirement age think they should also work longer. Even proponents acknowledge, however, that that isn’t always possible or compassionate. How could we carve out exceptions?

One approach would be to tie retirement benefit eligibility to years of work. In theory, that would protect lower-paid workers if they tend to start their careers relatively early and work more years before retiring than better-educated, higher-paid workers. But researchers have found that higher disability rates and greater employment volatility tend to offset lower-wage workers’ early labor force starts and lead to fewer total years of work. Overall, men and women with the least education have the fewest years of work. Meanwhile, although better-educated and higher-paid workers start their careers later, they tend to work more steadily.a

Another general approach is to tie retirement benefit eligibility to lifetime earnings. Critics of proposals to raise the retirement age agree that life expectancies are rising but note that the gains are not equally shared. People with greater education and higher income have enjoyed the largest gains in life expectancy.b That suggests tying Social Security’s retirement age to some measure of lifetime earnings — such as what is known as the Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME). But the link between life expectancy and AIME seems stronger for men than women. For married couples, using the higher AIME (typically the husband’s) would seem to work better, but such an approach would be hard to administer.c In any event, a rule based on statistical correlations is bound to be inequitable in a substantial number of cases.

Some people suggest tying the retirement age to occupation (for example, manual versus “desk” work). Even assuming that policymakers could devise fair rules to do so, they would face the stumbling block that the government does not collect occupational histories, except in a single self-reported line on taxpayers’ annual tax returns.

Some others advocate liberalizing Social Security disability benefits for older workers. That could take the form of easing the requirement that applicants must have worked in five of the last ten years, the disability criteria themselves, or both. The Social Security Disability Insurance program, however, already considers applicants’ age, education, and occupation — in addition to their medical condition — when considering their ability to perform other work (assuming that they can no longer do their previous jobs). In addition, liberalizing the disability criteria would further overload a system that the federal government runs jointly with the states and that already is staggering under a very large volume of applications.

In short, although advocates of raising the retirement age often express concern about such a policy’s effect on vulnerable older workers, they haven’t yet found an equitable and administratively practical way to carve out exemptions.

a. Melissa M. Favreault and C. Eugene Steuerle, “The Implications of Career Lengths for Social Security,” Urban Institute Retirement Policy Program Discussion Paper 08?03, April 2008.

b. Joyce Manchester and Julie Topoleski, “Growing Disparities in Life Expectancy,” Congressional Budget Office Issue Brief, April 2008.

c. Courtney Monk, John A. Turner, and Natalia A. Zhivan, “Adjusting Social Security for Increasing Life Expectancy: Effects on Progressivity,” Boston College Center for Retirement Research Working Paper 2010-9, August 2010.

If there were no exemptions, the higher retirement age would cut benefits for an age-65 retiree by about 8 percent in 2050 and 15 percent in 2080. The actuaries often depict the effect of Social Security proposals by using hypothetical examples of workers at various earnings levels. Under this depiction, the benefit reduction from Bowles-Simpson’s rise in the retirement age is quite visible for higher-paid workers but appears to be zero for lower earners. This appearance, however, is misleading. The earners in the actuaries’ hypothetical examples all have extremely steady work histories, with earnings in every single year from their early 20s through age 64. In real life, that’s unusual, especially for lower-paid workers. Indeed, the actuaries themselves estimate that under these criteria, only about 20 percent of workers with very low lifetime earnings (averaging about $10,771) would qualify for the hardship exemption from the higher retirement age. [20]

Workers with very low lifetime earnings tend to have irregular earnings histories in part because they have less education and skills, are often the first fired when the economy weakens and the last hired back when it strengthens, and include many low-wage female workers who spent years out of the workforce raising children. Similarly, the actuaries estimate that about 70 percent of those with low (as distinguished from very low) lifetime earnings (averaging about $19,388) would qualify for the hardship exemption. As a result, millions of the nation’s lowest-income workers would not be protected and would face benefit cuts, even though their Social Security benefits already are quite low.

In short, the rhetoric surrounding Bowles-Simpson’s retirement-age proposal and Social Security proposals in general — that they shield low-income workers from benefit cuts — does not match reality. Despite the co-chairs’ claim, the policy that the actuaries analyzed does not “best target the population for whom an increased [early eligibility age] poses a real hardship.” Criteria based solely on years of work and on earnings cannot accomplish that.

On a related note, raising Social Security’s early-eligibility age for most workers would likely spur more applications for disability benefits, adding to an overburdened Social Security disability benefits processing system. In addition, many of those affected would not qualify for disability, either because their impairment is not yet severe enough or because they have not worked in at least five of the last ten years (a requirement for those benefits).

Bowles-Simpson also would give all workers — including those who don’t qualify for the “hardship” exemption,” however implemented — an option to collect half of a Social Security benefit at age 62, while deferring the rest. The reduction in monthly benefits for early retirement would still apply. The co-chairs describe this as a flexible provision that would allow people to enter phased retirement. In fact, this is a hollow assurance. Social Security benefits are already low and would be cut under other provisions of Bowles-Simpson. Few workers with low or modest earnings could afford to retire on half of the remainder. And supplementing this meager half-benefit with earnings would subject the worker to the Social Security earnings test and result in a further reduction in the benefit amount.

Bowles-Simpson would provide an enhanced minimum benefit to certain long-term, low-paid workers. The benefit (before any reduction for early retirement) would equal 125 percent of the poverty line, or about $13,500 a year in 2010 dollars, for anyone with 30 “coverage years.” [21] The minimum benefit would be pro-rated for people with between 10 and 30 years of work. The required years of work would be reduced for disabled workers, depending on how old they were at the onset of their disability.

Bowles-Simpson’s minimum-benefit proposal suffers from several defects:

- It wouldn’t help — or wouldn’t help much — most people with low benefits , because they wouldn’t have enough “coverage years.” In general, people with very low Social Security benefits have an irregular earnings history, with significant periods out of the labor force. The reasons may include unemployment, family responsibilities, poor health, and many others. The likelihood of earning a Social Security retirement benefit that was below the poverty line was 42 percent among workers who had 10 to 19 years of coverage, but just 10 percent among those with 30 or more years of coverage, according to one study. (Among the subset of long-term workers with a below-poverty benefit, certain groups were over-represented: high-school dropouts, non-Hispanic African-Americans, people without a marriage lasting more than 10 years, and people who had worked in farming, forestry, and fishing, in services, or as operators. [22])

- It is poorly targeted . It’s possible to earn a year of coverage — which requires $4,480 in earnings, in 2010 dollars — with part-time or part-year work. As a result, some of the additional benefits that the minimum benefit would provide would go to relatively affluent individuals, such as people who worked part time and are married to a high-earning spouse and people who spent much of their careers in noncovered employment, such as work for state or local governments, and had some part-time or part-year work (such as work during the summer) on the side. [23]

- It contributes to a flatter benefit structure and may reduce incentives to work and to pay taxes . As noted earlier, Bowles-Simpson cuts benefits sharply for people with average and above-average earnings. Meanwhile, the minimum-benefit proposal would raise benefits for some people with low earnings. The overall effect is to compress the benefit structure. Once people worked long enough to qualify for the minimum benefit, they often would get little or no additional return for their extra work and higher payroll taxes. In fact, for the self-employed, the minimum-benefit proposal included in Bowles-Simpson would create an incentive for underreporting earnings and underpaying taxes.

- It could actually harm some beneficiaries . Some people who qualify for the minimum benefit would otherwise have collected Supplemental Security Income (SSI), a means-tested benefit that aids elderly or disabled people with little income and few assets. SSI benefits equal about three-fourths of the poverty line. Crucially, SSI eligibility also confers Medicaid coverage. Boosting these beneficiaries’ Social Security income may disqualify them from SSI — and hence from Medicaid, which can have a calamitous effect if they have high health-care expenses that are not covered by Medicare. Any proposal to establish a minimum benefit must be accompanied by an adjustment in SSI and Medicaid eligibility rules to avoid making many poor beneficiaries worse off. Bowles-Simpson, however, includes no such an adjustment.

- Its implementation timetable is inequitable . The minimum benefit would help people who first become eligible for Social Security in 2017 or later, but offer nothing to people becoming eligible before then. That would create huge inequities — for example, between two long-term, low-paid workers who reach age 62 in 2016 and 2017, respectively. Social Security reforms should strive hard to avoid such disparities. (In the past, benefit reductions have generally been phased in gradually while benefit liberalizations have taken effect across-the-board. Implementing the minimum-benefit provision all at once also would substantially increase its cost.)

Social Security solvency proposals often include minimum-benefit provisions to make them look more progressive and to try to cushion the basic benefit cuts they include. Unfortunately, it is hard to design a well-targeted minimum benefit at reasonable cost. Rather than enact a poorly designed minimum-benefit provision as part of Social Security reform, policymakers should seriously consider alternatives, such as strengthening SSI.

Some provisions of Bowles-Simpson’s Social Security proposal have merit. But the package as a whole is not well-designed, cuts benefits excessively, harms many low- and moderate-income workers, and radically alters the program’s earnings-replacement philosophy.

Social Security reform deserves a debate on its own merits, with policymakers paying careful attention to its impacts on beneficiaries, taxpayers, and other programs such as SSI. Bowles-Simpson shows the pitfalls of drafting a reform package hurriedly as part of an overall deficit-reduction effort. It does not represent a sound “starting point” for Social Security reform.