- Home

- Medicaid Block Grant Or Funding Caps Wou...

Medicaid Block Grant or Funding Caps Would Shift Costs to States, Beneficiaries, and Providers

Would Also Unravel Health Reform Law

Proposals to convert Medicaid into a block grant or otherwise cap its funding are receiving renewed attention in the emerging debate over cutting federal spending. For example, Rep. Fred Upton (R-MI), the new chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, reportedly has already discussed block-granting Medicaid with some governors.[1]

Such proposals would have far-reaching adverse effects. In particular, they would shift costs and risks quite significantly to the states, to tens of millions of low-income Medicaid beneficiaries, and to the health care providers that serve those beneficiaries.

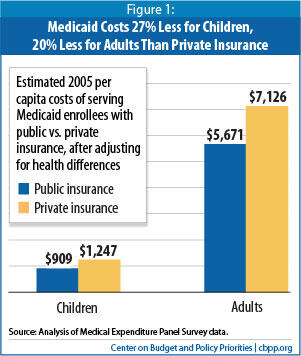

Currently, the federal government pays a fixed share of a state’s Medicaid costs. Under a block grant or funding cap, it would pay only a fixed dollar amount of a state’s costs, with the state responsible for all costs that exceed the cap. Proponents of block grants or funding caps say Medicaid’s costs are growing out of control, both because the federal government covers the same share of a state’s costs no matter how high they go and because states use creative financing mechanisms to maximize federal funding. But average annual Medicaid cost growth per beneficiary over the last 30 years has been no greater than health care cost growth systemwide and, in fact, Medicaid’s costs per beneficiary have been growing less rapidly in recent years than costs in private insurance. In addition, the average cost per beneficiary is significantly lower than under private coverage. Finally, the federal government has taken important steps to curb financial “gaming”; policymakers can take additional steps without entirely restructuring Medicaid’s finances and fundamentally altering the nature of the program.

If federal funding proved inadequate under a block grant or cap — which is likely because policymakers would give states less federal funding than they would receive under the current system in order to produce savings, and because federal funding would no longer rise in response to recessions, epidemics, or medical breakthroughs that improve health or save lives but at increased cost — states would have to contribute more of their own funds or cut back eligibility, benefits, and/or provider payments. Block-grant or cap proposals typically give states much more flexibility over Medicaid, so states would likely be able to cap enrollment, substantially scale back eligibility and coverage, and raise cost-sharing much more than they can today, with serious consequences for beneficiaries.

Converting Medicaid to a block grant would also undermine the health reform law. If federal funding were capped, states would not be able to expand their Medicaid programs in 2014 as the law requires, with the result that up to 16 million fewer of the uninsured would gain coverage. Moreover, a block grant would likely increase the ranks of the uninsured and underinsured over time by leaving states with funding levels that, with each passing year, fall farther and farther short of what states need to sustain their current Medicaid programs.

Because of the substantial risks that block grants or funding caps would generate, governors, state legislators, beneficiary groups that advocate on behalf of children, families, people with disabilities, and seniors, and providers such as hospitals, physicians, nursing homes, pharmacies, and insurers have opposed such steps during past block-grant debates in Congress (in 2003 and 1995).

How Medicaid Works Today

Medicaid provides health coverage to roughly 58 million children, parents, seniors, and people with disabilities and is administered by the states and the federal government. Medicaid also is jointly financed, with the federal government picking up between 50 percent and 75 percent of each state’s Medicaid costs (57 percent, on average) and the state responsible for the remainder. Federal Medicaid financing is open-ended; if state Medicaid spending rises, the federal government shares in the increased costs. If state Medicaid spending declines, the federal government shares in the resulting savings.

As a condition of receiving federal Medicaid funding, states must meet certain requirements in their Medicaid programs. For example, they must cover certain “mandatory” populations like children up to age 6 with incomes up to 133 percent of the poverty line and older children up to 100 percent of the poverty line, low-income seniors and people with disabilities who receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits, and low-income parents with incomes that would have qualified them for AFDC prior to enactment of the 1996 welfare reform law. Under the health reform law, states will have to expand Medicaid to all non-elderly individuals with incomes up to 133 percent of the poverty line, as of January 1, 2014. Unless they have a federal waiver, states cannot cap enrollment and must accept all eligible individuals who apply. States also have to cover certain “mandatory” benefits like hospital, nursing home, and physician care and Early Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) services for children. They generally cannot charge premiums and can require only modest co-payments, since most beneficiaries have very low incomes.

States have the option of covering additional populations, such as children with incomes above the minimum levels, and also can cover optional benefits. (For example, all states opt to provide prescription drug coverage.) States also have flexibility in setting reimbursement rates for health care providers. As a result, there is significant variation across state Medicaid programs in terms of eligibility, benefits, cost-sharing requirements, and provider rates.

How a Medicaid Block Grant Would Work

Under proposals to convert Medicaid to a block grant or otherwise cap federal funding, the federal government would no longer pay a fixed percentage of states’ Medicaid costs. Instead, the federal government would provide each state with a fixed dollar amount, with states responsible for all remaining Medicaid costs.[2]

Block-grant proposals vary on how this fixed amount would be determined, but typically a national Medicaid spending allotment would be set each year, and a formula would be used to determine each state’s share of that allotment. Alternatively, each state’s allotment could be calculated based on a formula, without regard to any national cap. While the amount provided each year could be frozen permanently (as is the case under the TANF block grant), most Medicaid block-grant proposals adjust the national or state allotment each year in order to reflect, to some degree, factors like growth in population, economic growth, or inflation.

Proposals to cap federal Medicaid funding also typically provide greater flexibility to states in designing their Medicaid programs, allowing them to bypass federal requirements related to eligibility and benefits. For example, states could be allowed to cap overall enrollment (or enrollment of certain populations) and institute waiting lists, drop coverage for some or all “mandatory” populations and benefits, and charge higher premiums and cost-sharing than they are permitted to do now. States could also be allowed to offer beneficiaries a voucher to purchase private insurance rather than provide coverage directly. Block-grant proposals typically include some sort of maintenance-of-effort (MOE) requirement that states continue to spend at least what they currently do on Medicaid, with potential annual adjustments to that MOE level.

Assessing Arguments for a Block Grant

Critics of Medicaid argue that program costs are growing out of control and that the current federal financing structure is a prime cause, because the federal government will pick up a percentage of states’ Medicaid costs however high those costs are. They also contend that the financing structure remains highly vulnerable to “gaming,” under which states use creative financing mechanisms to maximize federal funding. They claim that the only way to control federal Medicaid spending growth is to block-grant or cap federal funding.

These claims do not fare well under scrutiny. For example, over the past 30 years, average annual Medicaid cost growth per beneficiary has essentially tracked health-care cost growth systemwide.[3] In fact, in recent years, costs per beneficiary in the Medicaid program have been rising less rapidly than costs in private insurance.[4]

Moreover, while financial gaming by states has been a significant problem historically, the federal government has taken a number of steps over the past two decades to substantially curb such practices. Legislation enacted in 1992, 1997, 2000, and 2006, as well as various federal regulations and guidance, have imposed wide-ranging restrictions on states’ ability to draw down additional federal Medicaid funds through creative accounting. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported last year that, while further steps are needed, “Congress and [the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] have taken important steps to improve Medicaid’s fiscal integrity and financial management.”[6] Congress and the Administration can take additional targeted steps to address these issues (including further improved federal oversight) as GAO has recommended without changing Medicaid’s entire financing structure.

Would a Block Grant Provide Adequate Funding?

If a Medicaid block grant or federal funding cap is intended to produce savings, it must give states less federal funding each year than the current financing system would. Proposals typically accomplish this by increasing annual federal payments by a rate less than the current baseline growth rate, which reflects expected growth in enrollment, the aging of the population, and growth in health care costs. The current baseline growth rate is expected to be a bit more than 7 percent annually, according to CBO.

For example, one recent block-grant proposal[7] could adjust the federal block-grant funding level by up to 1.5 to 2 percentage points less each year than projected cost growth, with the difference compounding over time and growing quickly. [8] This plan would reduce federal Medicaid funding by $180 billion over the next ten years compared to current law, according to CBO.[9] States would not be able to sustain their Medicaid programs without increasing their share of the cost substantially or cutting the program back markedly.

Moreover, the actual funding reductions that a block grant would impose on states could turn out to be considerably larger than CBO’s official cost estimate would project, since federal funding would no longer increase to help cover unanticipated cost increases resulting from increases in enrollment or per-beneficiary health care costs. Consider the following:

- Economic downturns. When people lose their jobs and access to employer-sponsored insurance, many become eligible for and enroll in Medicaid. Enrollment increased by nearly 6 million people between December 2007 and December 2009, for example, according to a survey of states by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured.[10] As a result, annual Medicaid cost growth was 8.8 percent in 2010, the highest in eight years.[11] States also saw large growth in Medicaid enrollment and costs during the 2001 recession.[12] Under most block-grant proposals, federal funding would not respond to changes in the economy and would not rise during recessions.

- Higher health care costs resulting from new medical treatments or new health conditions. State Medicaid programs saw large unanticipated increases in costs when the HIV/AIDS epidemic first struck in the 1980s. Similarly, if a new treatment for AIDS or cancer that is effective but costly becomes available, that could significantly increase Medicaid costs; for example, state Medicaid programs experienced higher prescription drug costs when the HIV drug cocktail first proved to be effective. Such developments save lives and improve health but increase average Medicaid costs per beneficiary. Under a block grant, federal funding would not respond to such developments.

Risks for States

A Medicaid block grant would shift significant costs to states. Over time, as the block grant amount fell further and further behind what states would have received under the current financing system, states would be responsible for making up the difference.

They would also bear the risk of any large, unanticipated costs resulting from a recession or higher-than-expected health care costs, as explained above. Even under the current financing structure, states have had great difficulty absorbing the significantly higher Medicaid enrollment-related costs resulting from the economic downturn because those higher costs have coincided with plummeting state tax revenues and large budget shortfalls. In both the recent and previous downturns, Congress temporarily increased the share of Medicaid costs that the federal government pays in order to shore up state Medicaid programs and allow them to enroll millions more individuals and families as unemployment mounted. Under a block grant with capped federal Medicaid funding, recessions would pose much greater risks to states.

In addition, the cost-shift to states under a block grant would not be evenly distributed. Each state’s capped amount would likely be based largely on its current spending (for example, its current share of total federal Medicaid spending or its spending level in a base year), which would effectively lock in existing variations across state Medicaid programs. States that had relatively narrow Medicaid programs and/or relatively low provider reimbursement rates when the block grant was created would receive substantially fewer funds than other states. Such states would have to finance any subsequent improvements in their programs themselves, since no additional federal funds beyond the block grant amount would be available.

Under a block grant, states would thus have to contribute considerably more in general revenues to the cost of their Medicaid programs, or as is more likely, scale back their Medicaid programs to the detriment of beneficiaries.

Risks for Beneficiaries

As a state’s block-grant amount became increasingly inadequate over time, states would likely make up for the shortfall, at least in part, by exercising the greater flexibility they would be given to restrict enrollment, eligibility, and benefits. These cuts would likely become deepest at times when individuals and families most need Medicaid, such as during a recession.

Such cuts could be devastating for tens of millions of low-income Medicaid beneficiaries. For example, states might be given flexibility to cap Medicaid enrollment, leaving uninsured a substantial number of people whose low incomes would otherwise qualify them for Medicaid. Many current beneficiaries could also be made ineligible and end up uninsured, as states narrow coverage.

In addition, Medicaid provides certain benefits not typically offered by private insurance that are tailored to meet the needs of vulnerable beneficiaries — particularly people with severe disabilities — who have traditionally been excluded from the private insurance market. Such services, such as case management, therapy services, and mental health care, are critical for impoverished people with serious disabilities but are expensive; states faced with funding limits under a block grant might well opt to curtail them.

Similarly, children could lose access to EPSDT (Early Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment), a comprehensive pediatric benefit designed to ensure that low-income children receive preventive medical screening and treatment for health problems they are found to have. Private insurance typically does not provide such comprehensive pediatric coverage. This broader coverage is critical for poor children, particularly those with special health care needs, who often go without preventive care and advanced medical treatments they need if their insurance doesn’t cover those services, because their parents can’t afford to pay for the services.

As noted, Medicaid also ensures that coverage is affordable by generally not charging premiums and requiring only modest co-payments; research has found that premiums and cost-sharing tend to disproportionately lead poor households to forgo needed care or remain uninsured. Under a block grant, states could begin charging premiums that discourage enrollment (and leave people uninsured) and requiring burdensome deductibles and co-payments that reduce access to needed health care.

Under a block grant, states also could be allowed to shift beneficiaries into private insurance, offering them a voucher to purchase coverage on their own. As noted, however, Medicaid costs substantially less per beneficiary than private insurance, on average, largely due to its lower provider reimbursement rates and lower administrative costs. As a result, shifting beneficiaries into private insurance could raise states’ costs — unless states provided vouchers that purchased considerably less coverage than Medicaid provides. Because the block grant would provide less federal funding and private insurance costs more per beneficiary, a voucher system for Medicaid enrollees would be viable only if it covered significantly fewer beneficiaries (leaving more people uninsured) or left many of those who received a voucher underinsured (i.e., without coverage for certain important health care services or facing premiums, deductibles, or co-payments they could have great difficulty affording).

Seniors and people with disabilities would be at particular risk. They constitute just one-quarter of Medicaid beneficiaries but account for two-thirds of all Medicaid spending because of their greater health care needs and because Medicaid is the primary funder of long-term care services, particularly nursing home care. Capping federal Medicaid funding would place significant financial pressure on states to scale back coverage for low-income seniors and people with disabilities in spite of their greater needs.

Risks for Health Care Providers and Managed Care Plans

In some states, low reimbursement rates have impeded Medicaid beneficiaries’ access to physicians, particularly specialists. When addressing state Medicaid budget shortfalls, states have tended to focus first on provider reimbursement rates as a source of savings, including during the current economic downturn.[13]

It is likely that states facing inadequate block grant funding would seek to further scale back provider rates. These rate reductions likely would apply not only to hospitals, nursing homes, physicians, and pharmacies in Medicaid fee-for-service but also to managed care plans that currently serve low-income children and their parents in state Medicaid programs across the nation.

Sharp reductions in provider rates would likely cause more providers and plans to withdraw from Medicaid, which could threaten beneficiary access to needed care, particularly in communities that already are underserved. It also would place greater pressure on providers such as community health care centers and safety-net hospitals, which rely on Medicaid funding but which would — under a block grant — likely face increased patient needs because of increases in the numbers of uninsured individuals if Medicaid enrollment is capped and eligibility is restricted.

How Would a Medicaid Block Grant Affect Health Reform?

As noted, under the health reform law, state Medicaid programs will be required to cover all non-elderly individuals up to 133 percent of the poverty line ($29,400 for a family of four) starting in 2014. The federal government will pick up the vast majority of states’ costs for this coverage expansion — 96 percent of those costs over the next ten years, according to CBO estimates.[14] As a result of this expansion, CBO expects that by 2019, some 16 million more people will be enrolled in Medicaid than would have been the case under prior law but state costs will be only 1.25 percent higher than they would be in the absence of health reform. [15] The Medicaid expansion is one of the main reasons why the health reform law will reduce the number of uninsured people by an estimated 32 million by 2019, according to CBO.

Since federal Medicaid funding would be lower under a block grant than under the current funding structure, the federal government would pay for substantially less of the cost of the health reform law’s Medicaid expansion, making it far less viable. [16] In fact, because block-grant proposals typically give states much greater flexibility regarding Medicaid eligibility, it is difficult to see how states could still be required to institute the Medicaid expansion. Even if they were so required, far fewer newly eligible individuals and families would actually obtain coverage if a block-grant proposal also allowed states to cap Medicaid enrollment.

In addition, facing inadequate federal funding, state Medicaid programs that significantly scaled back their provider reimbursement rates would likely face the withdrawal of more health care providers from the program. Yet greater provider participation, particularly among primary care providers, will be needed to serve the millions of additional beneficiaries who will begin enrolling in 2014.

In short, the Medicaid expansion — one of the central coverage elements of the health reform law — is fundamentally incompatible with a block-grant structure. If Medicaid were converted to a block grant, the coverage expansion would almost certainly have to be scrapped. Millions more uninsured people, particularly those with very low incomes, would remain without coverage. This, in turn, would threaten the health reform law’s ability to improve health care coverage and quality.

Conclusion

Rising health care costs, along with aging of the population, are a primary contributor to our bleak long-term fiscal outlook, and slowing the overall rate of growth in health care costs is essential to reducing federal deficits and debt. However, cutting federal Medicaid spending in isolation, irrespective of the rate of health care cost growth systemwide — as proposals to block grant or cap Medicaid generally would do — represents a deeply flawed approach. It would shift costs and risks to states, low-income beneficiaries, and health care providers and lead to more of a two-tier health system in which poor people receive considerably less adequate care than other Americans. It also would likely unravel the health reform law, driving up the number of people who are uninsured and underinsured, while failing to address the problem of systemwide cost growth that affects private as well as public insurance.

Medicaid Costs Are Growing More Slowly Than Costs for Medicare or Private Insurance

Federal Government Will Pick Up Nearly All Costs of Health Reform’s Medicaid Expansion

End Notes

[2] For background and analysis of the block-grant proposals considered in 2003, see John Holahan and Alan Weil, “Block Grants Are the Wrong Prescription for Medicaid,” Urban Institute, May 27, 2003; Jocelyn Guyer, “Bush Administration Medicaid/SCHIP Proposal,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, May 2003; Cindy Mann, Melanie Nathanson, and Edwin Park, “Administration’s Medicaid Proposal Would Shift Fiscal Risks to States,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised April 22, 2003; and Edwin Park, Cindy Mann, Joan Alker, and Melanie Nathanson, “NGA Medicaid Task Force’s Draft Proposal Shifts Fiscal Risks to States and Jeopardizes Health Coverage for Millions,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 5, 2003.

[3] See, for example, Richard Kogan, Kris Cox, and Jim Horney, “The Long-Term Fiscal Outlook Is Bleak,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 16, 2008.

[4] Leighton Ku, “Medicaid Costs Are Growing More Slowly than Costs for Medicare or Private Insurance,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 13, 2006.

[5] Leighton Ku and Matthew Broaddus, “Public and Private Insurance: Stacking Up the Costs,” Health Affairs (web exclusive), June 24, 2008. See also Jack Hadley and John Holahan, “Is Health Care Spending Higher Under Medicaid or Private Insurance?,” Inquiry 40: 323-342, Winter 2003/2004.

[6] Government Accountability Office, “High-Risk List: An Update,” January 2009.

[7] The plan referred to here is part of a proposal presented to the President’s fiscal commission, chaired by Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson, by Representative Paul Ryan (R-WI) and Alice Rivlin. Bowles and Simpson declined to accept this proposal.

[8] CBPP estimates. Another deficit reduction plan proposed by Alice Rivlin and Pete Domenici, which a commission of the Bipartisan Policy Center unveiled in November, would limit annual growth in federal Medicaid spending by 1 percentage point per year.

[9] Congressional Budget Office, “Letter from Douglas W. Elmendorf to the Honorable Paul D. Ryan,” November 17, 2010.

[10] Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, “Medicaid Enrollment: December 2009 Data Snapshot,” September 2010.

[11] Vernon Smith, Kathleen Gifford, Eileen Ellis, Robin Rudowitz, and Laura Snyder, “Hoping for Economic Recovery, Preparing for Health Reform: A Look at Medicaid Spending, Coverage and Policy Trends,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, September 2010.

[12] Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, op cit.

[13] Smith et al., op cit.

[14] The federal government will pick up 100 percent of the costs of newly eligible individuals for the first three years and no less than 90 percent of those costs in 2020 and thereafter.

[15] January Angeles and Matt Broaddus, “Federal Government Will Pick Up Nearly All Costs of Health Reform’s Medicaid Expansion,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised June 18, 2010.

[16] The Ryan-Rivlin plan would initially exclude funding for the Medicaid expansion from the block grant, but starting in 2021, the expansion would be subject to the overall block grant amount.