Tax Data Show Richest 1 Percent Took a Hit in 2008, But Income Remained Highly Concentrated at the Top

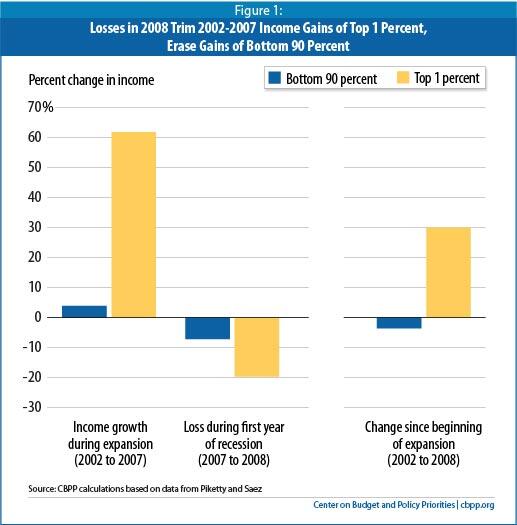

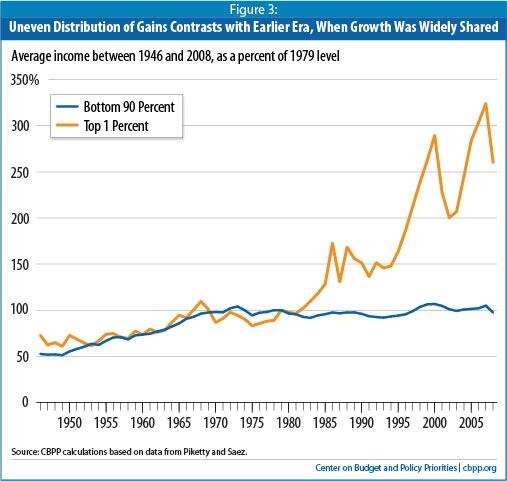

Recent Gains of Bottom 90 Percent Wiped Out

End Notes

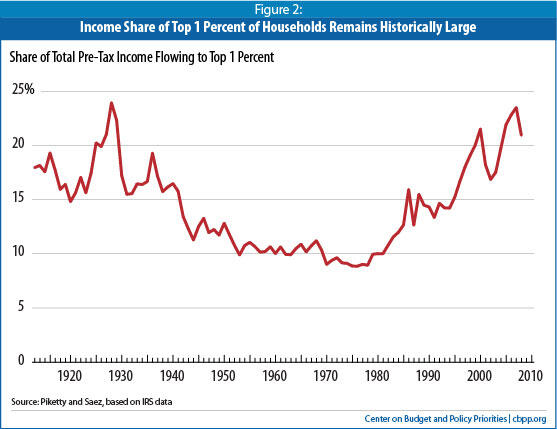

[1] Piketty and Saez rely on detailed Internal Revenue Service micro-files for available years, extending the full series to 1913 using aggregate data and statistical techniques. Their July 2010 revision incorporates the detailed micro-files for 2008 that have recently become available. For details on their methods, see Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, “Income Inequality in the United States: 1913-1998,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, February 2003, or, for a less technical summary, see http://elsa.berkeley.edu/~saez/saez-UStopincomes-2007.pdf. Their most recent estimates are available at http://elsa.berkeley.edu/~saez/TabFig2008.xls.

[2] The IRS data used by Piketty and Saez have some limitations, one of the most important of which is that they do not include people who do not file income tax returns. These people are included in the data used by the Census Bureau in its annual calculation of median household income, but the Census data have incomplete information about income at the very top of the distribution. Also, neither Piketty-Saez nor Census adjusts incomes for family size, which can distort trends when average family size is changing over time. The Congressional Budget Office publishes an analysis combining the data used by Piketty-Saez and Census to estimate average federal tax rates paid by households in various income categories, as well as before- and after-tax household income adjusted for family size. CBO thus provides the most comprehensive analysis of income distribution, but is not as timely as the Piketty-Saez analysis. The most recent CBO report uses 2007 data and provides historical data only back to 1979. (See http://www.cbo.gov/publications/collections/collections.cfm?collect=13.)

[3] The last economic expansion began in November 2001 and ended in December 2007. However, the real income of the top 1 percent of households did not reach a trough until 2002 and that of the bottom 90 percent until 2003. For the purposes of this paper, we measure income growth between 2002 and 2007. If we had chosen 2001 as the base year, the share of income gains accruing to the top 1 percent of households would have been 76 percent and that of the bottom 90 percent of households would have been 2 percent. If we had chosen 2003, those respective shares would have been 59 percent and 20 percent.

[4] As discussed earlier, the Piketty-Saez data are particularly useful for analyzing long-term trends at the very top of the income distribution. They have some limitations for the bottom 90 percent, however, an important one of which is that they do not include households that do not file income tax returns. Other data sources show modestly larger or smaller gains for the bottom 90 percent, but all show a sharp discrepancy in income growth between the top 1 percent of households and everyone else.

[5] Emmanuel Saez, “Striking It Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States,” Pathways Magazine, Stanford Center for the Study of Poverty and Inequality, Winter 2008 (updated July 17, 2010), http://elsa.berkeley.edu/~saez/saez-UStopincomes-2008.pdf.