In anticipation of Congressional reauthorization of the federal child nutrition programs, some have called for increased federal reimbursement rates for school meals to improve their nutritional quality. [2] Under current rules, however, federal payments for free and reduced price meals are not used solely to underwrite the cost of producing those meals.

Research conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has consistently shown that in some school food programs, the federal reimbursements for free and reduced price meals appear to subsidize meals provided to higher income children and foods that are offered outside the federal school meal programs, such as less nutritious snack foods and individual items in vending machines.[3]

As a result, higher reimbursement rates would not necessarily result in school meal programs purchasing healthier foods. Instead, increased reimbursements could be used for any number of purposes, including keeping down the price of meals for better-off students or subsidizing less nutritious foods.

Whether or not Congress chooses to increase reimbursements, the first step to providing resources for higher quality school meals is to ensure that federal reimbursements for free and reduced price meals are used for their intended purpose — providing nutritious breakfasts and lunches to low-income school children.

School food authorities (SFAs, the entities that operate meal programs for school districts) maintain a single nonprofit, food service account. All revenues associated with food programs are collected in this account, and those funds may be spent on any nonprofit food service operations, including food sold outside of the federal school lunch and breakfast programs.

School food programs have four main sources of revenue:

- Federal school meal reimbursements account for about half of school food service revenues on average, though the percentage varies across districts and schools.[4] SFAs receive a specified federal reimbursement for each meal they serve that meets nutritional requirements. School districts receive the highest per-meal rates for meals served free or at a reduced price to children whose household income is below 185 percent of the poverty line.[5] School districts receive a lower per-meal rate (known as the “paid” rate) for meals served to children with incomes above this level.[6] (See Table 1.) (Each free, reduced price, and paid meal also receives federal support in the form of commodities, but that support is not included in this breakdown of revenues.[7])

- Student payments for federally reimbursable meals account for about one-quarter of school food service revenues, on average. [8] Schools may charge up to 30 cents for a reduced price breakfast and up to 40 cents for a reduced price lunch.[9] School systems set the price of “paid” meals served to children with household income above 185 percent of the poverty line.

- Schools may offer foods sold outside of the federal school meal programs — referred to as “competitive” foods because they are sold in competition with federally reimbursed meals — such as individual items sold in the cafeteria or food and beverages available through vending machines. Payments for competitive foods account for about 16 percent of school food service revenues, on average.[10]

- State and local government contributions account for the remaining 9 percent of school food revenues, on average. [11] States are required to provide a small amount of matching funds to each SFA, and some states provide per-meal reimbursements in addition to the federal reimbursement. On average, local governments and school districts contribute more to school food programs than states. Some school districts also provide in-kind support to school food programs by not charging the food program for overhead costs like janitorial or payroll services.

- Free meals: Meals that meet the nutritional requirements of the National School Lunch or School Breakfast Program and are served at no charge to children with household income at or below 130 percent of the poverty line

- Reduced price meals: Meals that meet the nutritional requirements of the National School Lunch or School Breakfast Program and are served to children with household income above 130 percent of the poverty line and at or below 185 percent of the poverty line for no more than 40 cents for a lunch or 30 cents for a breakfast

- Paid meals: Meals that meet the nutritional requirements of the National School Lunch or School Breakfast Program and are served to children with household income above 185 percent of the poverty line at a price set by the school district or school food program

- Competitive foods: Food sold outside the National School Lunch or School Breakfast Program, such as individual items or less nutritious meals served in the cafeteria or individual items in vending machines

In general, school food programs have three main types of costs:

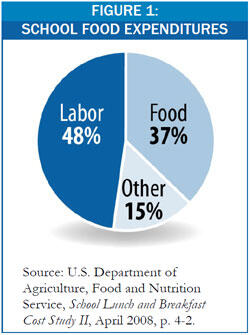

- Labor costs account for nearly half of expenditures, on average (48 percent).[12] They include the cost of the staff who prepare and serve food as well as those who perform the administrative functions associated with operating a meal program.

- Food costs account for more than a third of costs, on average (37 percent).[13]

- All other costs, including supplies, equipment, and indirect charges by the school district, account for about 15 percent of expenditures, on average.[14]

| TABLE 1:

National School Lunch Program 2009-2010 Reimbursement Rates* |

| Meal Category | Rate** |

| Free | $2.68 |

| Reduced Price | $2.28 |

| Paid | $0.25 |

| * These rates apply in the contiguous states. For the higher rates for Alaska and Hawaii, see http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/ Governance/notices/naps/nsl09-10fr.pdf . **SFAs that serve more than 60% of their lunches to children who qualify for free or reduced price meals receive an extra 2 cents per meal for each meal category. Each meal, regardless of category, also receives 19.5 cents worth of commodities from the federal government. |

School districts have broad discretion over the use of the revenues they receive, including federal reimbursements for free and reduced price meals. They may spend them on any nonprofit school food program that the school or district operates. There is no regulatory requirement that federal reimbursements for free and reduced price meals be spent only on those meals or that records differentiate between the costs and revenues of the various aspects of the school food program.

This kind of flexibility helps food service directors manage their programs and direct funds where needed. For example, an SFA might use revenues associated with its lunch program to defray some of the costs of offering a breakfast program. But this degree of flexibility also makes it nearly impossible to direct federal reimbursements to specific purposes or to guarantee that reimbursements for free and reduced price meals are being spent only on those meals.

By placing some parameters on school food budgets as part of reauthorization legislation, Congress could generate funds for the meals programs and ensure that federal funds are spent on the purposes that it intends. As explained below, two possible uses of school food revenue — subsidizing paid meals and providing competitive foods — raise concerns that low-income children may not be getting the full benefit of the federal reimbursements intended for those meals.[15]

Students who do not qualify for free or reduced price meals because their family income exceeds 185 percent of the poverty line may purchase “paid” meals, which receive a modest federal subsidy that supplements the price their parents pay for such meals (see Table 1).

According to a recent USDA study, the price that school districts charged for paid lunches during the 2004-2005 school year varied considerably, ranging from 65 cents to $3.00. The average price was $1.60, with $1.50 the most common price.[16] Typically, school districts or school boards set these prices. When combined with the federal reimbursement for that school year of 21 cents per paid lunch, the average total revenue an SFA collected for a paid lunch was $1.81.[17]

USDA’s school meal cost studies distinguish between “reported” and “full” costs. Reported costs are those costs charged to the school food service account. Food and labor made up 90 percent of reported costs during the 2005-2006 school year, with the remaining 10 percent attributed to contract services, supplies, and indirect charges by school districts.a

Full costs include reported costs as well as costs that could be charged to school food authority budgets but are not. Instead they are incurred by the school district in support of the food service program but not charged to the school food service account. Unreported costs primarily include labor, equipment depreciation, and indirect costs (such as accounting, purchasing, communication services, employee benefits, payroll taxes, and insurance). b

Unless otherwise noted, this paper relies on reported costs when analyzing school food service finances. While unreported costs could legitimately be charged to the school food service account, in practice these costs may not be easily identified and allocated to the school food service program and are not part of the food service budget. By relying on reported costs rather than full costs, this paper likely understates the gap between revenues from paid meals and competitive foods and the costs of providing them.

a See U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, School Lunch and Breakfast Cost Study II, April 2008, p. 3-5.

b See U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, School Lunch and Breakfast Cost Study II, April 2008, p. 4-2.

How much should school districts charge for a paid meal? School districts generally want to set a price that is affordable for the wide range of families with incomes in the paid meal category. Families with incomes just above 185 percent of the poverty line face much tighter household budgets than those with significantly higher incomes. Also, the charge should not be so high as to drive away too many children who otherwise would purchase paid meals; keeping better-off children in the program reduces the potential that children eating free and reduced price meals will be stigmatized. [18] In addition, higher participation among all children allows for economies of scale and may lead to lower costs per meal.[19]

SFAs would be well served by setting paid meal prices at a level that, when combined with the federal meal subsidy, at least covers the cost of producing the meal. A recent USDA study shows, however, that on average, SFAs set prices lower than that level. The average reported cost of providing a reimbursable lunch was $2.28 during school year 2005-2006.[20] As noted above, the average total revenue for a paid meal during 2004-2005 was $1.81. Even assuming an increase in average total revenue for paid meals the following year, it is unlikely that it came close to the average cost per meal.[21]

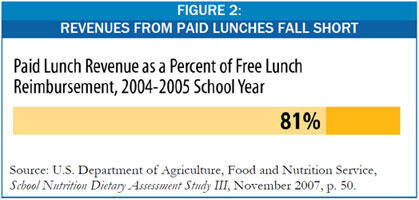

Another way to assess whether the price charged for a paid meal is sufficient is to compare it (after adding the federal meal subsidy) to the federal reimbursement for free meals. The federal reimbursement for free meals is one measure of how much is intended to be spent on producing a reimbursable meal.

For the 2004-2005 school year, in which, as noted above, the average total revenue for a paid lunch was $1.81, the federal reimbursement for a free lunch was $2.24.[22] Thus, the revenue associated with paid meals equaled only about 81 percent of the federal reimbursement provided for free lunches, even though the meals themselves were identical.

An analysis of the lunch prices charged by the 20 largest school districts for the 2009-2010 school year indicates that this practice continues. These school districts, which serve more than 10 percent of the nation’s school children, charge an average of $1.80 for an elementary school meal and $2.14 for a high school meal.[23] When combined with the 27 cent federal reimbursement for most paid lunches, this means these districts are collecting, on average, $2.07 for each paid lunch in elementary schools and $2.41 in high schools. [24] Since the federal reimbursement for a free meal is $2.68 (see Table 1), the revenue generated by each paid meal in these districts falls 61 cents short in elementary schools and 27 cents short in high schools, on average.

Stated another way, the average revenue for a paid lunch in these largest school districts is only about 77 percent of the federal reimbursement provided for free lunches in elementary schools and 90 percent of the federal reimbursement in high schools. There is an obvious disparity between the funds made available by the federal government to support free meals for low-income students and the revenue collected by school districts (from federal “paid” meal reimbursements and student payments) to support the very same meals when served to children at higher income levels. The disparity results in a revenue shortfall that undermines the goal of providing the highest quality meal possible to all students.

If these 20 districts brought paid lunch prices up to $2.43 — which, when combined with the federal reimbursement, would generate as much revenue per meal as the federal reimbursement for a free meal — they would increase their revenues by more than $55 million this year alone. That is as much added revenue as districts would receive if the federal reimbursement rate for all lunches were increased by 11 cents. [25] Setting prices closer to that level in smaller suburban and rural districts where a greater share of students eat paid meals could have even more of an impact on revenues and offer more benefit for low-income students.

When SFAs set paid meal prices at a level that does not allow them to cover the costs of providing the meals, they must make up the gap with another revenue source. Often, they use part of the federal reimbursements for meals served to low-income children. This practice effectively increases the federal subsidy for more affluent children above the level provided by Congress through paid meal subsidies. If the price charged for paid meals, combined with the federal per-meal subsidy, covered the costs of these meals (or equaled the federal per-meal reimbursement for free meals), more funds could be put toward providing more nutritious meals, providing better compensation and professional support to food service staff, or other improvements that would benefit children.

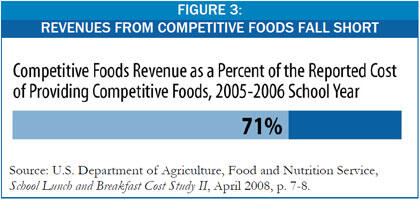

Most schools also fail to generate enough revenue from the sale of competitive foods to cover the cost of purchasing, preparing, and serving them. Competitive foods include items served in the cafeteria that are not part of a reimbursable meal (such as individual food items or meals that do not meet the nutritional requirements for the federal programs), individual food items in vending machines, and meals served to adults. Federal reimbursements are not provided for such foods, but under current USDA policy, the federal reimbursements provided for school meals may be used to subsidize the costs of providing competitive foods.

A 1994 USDA study found that revenue from reimbursable meals exceeded the cost of producing those meals and that school districts used the surplus revenues to subsidize competitive foods.[26] A more recent USDA study found that, on average, revenue from the sale of competitive foods during the 2005-2006 school year covered only 71 percent of the reported cost of providing such food. [27] The study concluded that because most SFAs break even overall, the average SFA used revenues from reimbursable meals to offset losses from competitive foods. The authors observed: “A major finding of [the 1994 study] was that school food authorities … subsidize the cost of nonreimbursable meals with overall excess revenue generated from all reimbursable meals. This was also the case in [the 2008 study].”[28]

Despite these findings, a common misperception lingers that competitive foods are an important source of funds for school food service operations. The discrepancy seems to arise from considering the

revenues associated with competitive foods without considering the

costs associated with providing them. A 2005 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report demonstrates this kind of omission. The report found that, during the 2003-2004 school year, many schools raised a substantial amount of revenue through competitive food sales.

[29] But the report

did not consider the cost of providing competitive foods. Therefore, the report’s authors could not analyze whether the revenues generated by the sale of competitive foods covered the cost of those foods. When this limitation was noted by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service (FNS), the authors responded: “We agree with FNS that our report focused on revenues generated by competitive food sales and that we did not determine if revenues generated by competitive food sales were sufficient to cover the actual cost of the foods sold.”

To be sure, schools incur some overhead costs (such as lighting for the cafeteria) regardless of whether they offer competitive foods. [30] Offering competitive foods does increase other costs, however, such as the cost of the food itself. In addition, if a cafeteria employee prepares competitive foods or serves children who are not taking a full meal, a share of that employee’s time is being devoted to competitive foods. When schools offer both a school meals program and competitive foods, the federal government does not need to underwrite all of the operating costs of the entire program; it is reasonable to expect the revenue generated by competitive foods to cover a share of production, service, and overhead that can reasonably be attributed to providing those foods. But if schools set prices without including a share of such costs, revenues may not be sufficient to cover the total costs of competitive foods, resulting in a funding gap that must be filled from other sources, including federal funds.

Because most school districts do not keep detailed records regarding the cost and revenue associated with various components of the school food program, it is often difficult to gain a clear picture of how they use federal reimbursements (except where USDA has conducted rigorous studies). This comingling of funds perpetuates misperceptions regarding the significance of the contribution of competitive foods to overall program finances.

Schools can fill the funding gap for paid meals and competitive foods in a number of ways. The local school district may appropriate dedicated funding to keep prices low. It may provide in-kind support (which in effect means that funds that could go toward other educational expenses are supporting meals for better-off children or competitive foods). As the studies discussed above suggest, schools also may rely on the federal reimbursements provided for meals served to children who qualify for free or reduced price meals. Or, they may use some combination of these options.

Under USDA’s interpretation of the law, there is nothing illegal about using reimbursements for free and reduced price meals to make up for losses associated with paid meals or competitive foods.[31] Once school districts have earned federal reimbursements through the National School Lunch or School Breakfast Programs by serving reimbursable meals, they may spend the funds on any nonprofit school food program they operate. School districts are permitted to combine revenues from reimbursable and non-reimbursable food sales as long as they maintain a nonprofit school food service.[32]

Because, on average, the prices charged for paid meals and competitive foods do not cover the cost of providing those foods, as explained above, this system facilitates cross-subsidization of paid meals and competitive food with federal reimbursements for free and reduced price meals.

Many agree that additional resources are needed to enable schools to improve the nutritional content of school meals and offer children more fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains. Some have called for raising federal reimbursement rates to provide these resources. Evidence suggests, however, that two key policy changes could enable school districts to achieve this goal by capturing additional revenues from within the program. These changes are necessary to ensure that any increase in reimbursement rates is used to improve meals, not to keep down prices for paid meals or competitive foods.[33] Moreover, these changes would help to ensure that taxpayer dollars provided for low-income children are used to provide nutritious meals for such students.

First, Congress could ensure that federal per-meal reimbursements are not used to cover costs associated with foods offered outside of the federal school meals programs. If schools want to offer competitive foods, the revenue from the sales of such food (and any non-federal revenues that state or local governments or school districts choose to provide) should cover the costs, without federal cross-subsidies.

Second, Congress could put school food programs on a path toward generating revenue for each paid meal that is comparable to that generated by each free or reduced price meal. It could do so by requiring school districts that charge lower prices to increase prices gradually so that, when combined with the federal subsidy provided for such meals, they eventually at least equal the federal reimbursement level for free meals.

Gradually increasing the paid lunch prices to levels that would begin to close the gap between paid meal revenues and free meal revenues would generate an estimated $2.6 billion in additional revenue for schools over ten years.[34] This is comparable to the additional revenue that a 4.5 cent across-the-board increase in the federal reimbursement rate for all school lunches would generate. It is important to keep in mind, however, that revenues would rise only in districts currently charging prices below any newly established minimum level. In addition, some school districts might reduce their level of support for school food programs once revenues increase, which would reduce the net revenue increase to the school food program (though it would free up resources for other educational purposes).

Raising prices for paid meals to more equitable levels may meet with resistance. Of particular concern are those children with family incomes just above 185 percent of the poverty line. Price increases that disproportionately drive these children from the meal programs would not be desirable. Data suggest, however, that children just over the 185 percent limit would not be disproportionately affected. USDA found that with paid meal prices between $1.50 and $2.00 per meal, participation of children just above the 185 percent threshold remains relatively stable. [35]

In addition, school officials may be concerned that increasing paid meal prices will drive better-off students away from the program. Because higher participation rates allow for economies of scale, a decrease in participation could drive up the cost per meal. However, the USDA study noted above found that participation was only about 3 percent lower in districts that charged $2.00 per meal as compared to $1.50 per meal. [36]

School districts also can take steps to shore up participation in the school meals program. Several studies have found that decreased access to competitive foods leads to increased participation in the National School Lunch Program and subsequent increases in federal reimbursements and overall revenue.[37]

In order to make sound decisions about meal pricing, school officials need more information. (They do not have opportunities to raise and lower prices to measure the resulting effects.) To remedy this information gap, USDA could publish and analyze existing meal price data for all districts. Examining what comparable districts are doing would help districts set prices above a federally required minimum while maintaining adequate participation.

The above changes would increase SFA resources without raising federal reimbursement rates (and thus federal costs). They also would help ensure that federal reimbursements for free and reduced price meals benefit low-income children. If increases in reimbursement rates prove desirable, the changes discussed here would help ensure that the added federal funds are actually used to provide more nutritious school meals. Thus, the changes outlined here are necessary preconditions to any reimbursement rate increases.

Under the current structure, a portion of federal meal reimbursements designated for low-income children appears to be subsidizing meals for children whose families are much better off and foods that are offered outside the federal school meal programs and may not meet federal nutrition standards.

Congress is now considering raising reimbursement rates. It is often assumed that such increases would result in healthier meals. But if Congress increases reimbursement rates without reforming the use of federal funds in school food budgets, the end result could be significant costs to taxpayers coupled with little improvement in the quality of meals served. Instead, the additional funds could be used in significant part to cover overhead expenses, keep prices down for better-off students, or subsidize less nutritious competitive foods. Even if reimbursement rate increases were tied to meeting enhanced nutritional requirements, the full benefit of the additional funds would be realized only if reimbursements for free and reduced price meals were not siphoned off to keep prices low for paid meals or competitive foods.

To ensure that federal funds directed towards children at risk for hunger or food insecurity are used to provide meals that meet their nutritional needs, it is important that families who can afford to pay their fair share do so. Prices for paid meals should be brought to levels that, when combined with the federal subsidy, actually cover the cost of providing those meals. Data suggest that, if accomplished gradually, this would not significantly reduce participation. In addition, federal funds should not be used to subsidize competitive foods.

Putting such policies in place would generate revenue that could be devoted to providing healthier meals to all students. Such changes also would help low-income children obtain the full benefit of federal reimbursements for free and reduced price meals. To be sure, there still would be no guarantee that a reimbursement rate increase would be spent on healthier foods rather than other priorities, such as training for food service staff. But without these changes, the odds of that occurring would be significantly lower.