- Home

- Federal Fiscal Relief Is Working As Inte...

Federal Fiscal Relief Is Working As Intended

As dire as the states’ fiscal condition is — with dramatic revenue downturns leading in some cases to unprecedented service cuts — evidence shows this bad situation would be substantially worse if not for federal recovery assistance.

The $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act package enacted in February included about $140 billion for states to use in various ways to help lessen the need for spending cuts, service reductions, and such other budget-balancing actions as tax increases. These funds were expected to provide states on average with about 40 percent of what they need to keep budgets in balance in the 2009, 2010, and 2011 fiscal years.

To date it appears that the funds are working as intended. They are enabling states to balance their budgets with fewer cuts in public services that would harm residents and further slow the economy.

Although the evidence is far from complete, the available information so far suggests that:

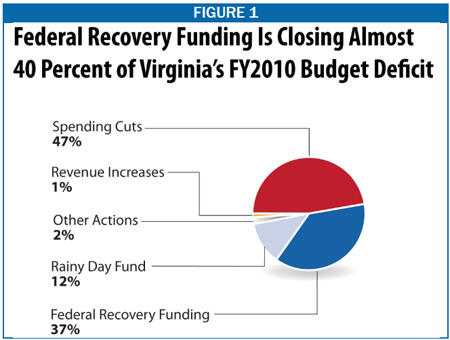

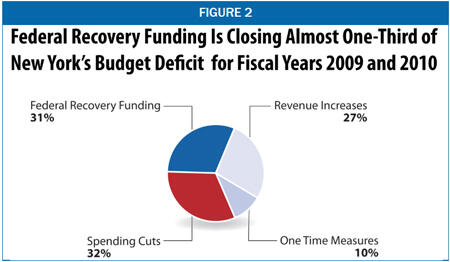

- The federal aid is enough to close, on average, roughly 30-40 percent of state budget shortfalls. The $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) included approximately $135 billion to $140 billion for states to maintain current programs, which are being squeezed between rising demand for services and sharply declining tax revenues. These ARRA dollars closed 31 percent of New York’s budget gap and 37 percent of Virginia’s. Other states, such as Georgia, Maryland, Utah, Washington, and West Virginia report similar outcomes. States are closing the remaining gaps with a mix of spending cuts, revenue increases, withdrawals from reserve funds, and other measures.

- The federal aid is arriving at a crucial time. States were seriously considering even more severe cuts than were enacted in such services as health care, education, and public safety prior to passage of federal stimulus legislation. Those cuts very likely would have taken place in the absence of the federal aid.

The examples of two states in particular are instructive. In both New York and Virginia, major cuts that had been proposed before the federal assistance was made available were never enacted. Virginia is using the fiscal assistance to keep open three facilities serving persons with mental health needs, reverse a planned cut in Medicaid payments to hospitals, lessen a reduction in aid to universities that almost certainly would have led to large tuition increases, avoid a major education budget cut, and avoid a funding cut that would have resulted in the loss of an estimated 310 deputy sheriffs’ positions. The governor had proposed these cuts before the federal funds became available.

New York is using recovery-act assistance to sustain state-funded pharmaceutical coverage for seniors on fixed incomes; maintain aid to hospitals and nursing homes; avert a proposed reduction in payments to low-income residents who are elderly, blind, or have disabilities; undo a proposed $1.1 billion cut in K-12 funding; reduce a proposed funding cut for community colleges; maintain programs that provide professional development for teachers; and avoid cuts in college tuition assistance for low- and moderate-income students. The aid also allowed New York to avoid shifting special education costs to local school districts, which would have had to cut services or raise property taxes more than they already are. As in Virginia, all of these cuts had been proposed by the governor prior to ARRA.

In addition, the federal aid undoubtedly is averting other, unspecified cuts in Virginia and New York. In both states, the governor’s proposed spending reductions prior to ARRA would have been insufficient to balance the budget as the revenue situation worsened. - The flexibility afforded by ARRA dollars is important. ARRA’s state fiscal assistance consisted primarily of $87 billion in increased Medicaid funding and a creation of the $50 billion State Fiscal Stabilization Fund administered by the federal Department of Education. (See the text box on page 3.) As ARRA requires, states are using most of these dollars for health care and education. However, the availability of the federal funds also allows states to use available state money to protect other important programs not specifically supported through ARRA.

Again, New York and Virginia are instructive. New York used some of its savings resulting from the additional federal Medicaid funding to restore aid for New York City, while Virginia used ARRA Medicaid savings to help address an $820 million revenue shortfall that otherwise would have resulted in deeper cuts in a range of areas. States also are receiving money for criminal justice, human services, family assistance, child care, and other areas that they can, under some circumstances, use to pay for programs that otherwise would have been cut. - Federal aid will continue to play an important role as states — and the national economy — recover. Most expect budget problems to continue at least through 2011, and many states are planning to time the use of federal dollars so that some of the funds will be available for that year (which the federal law allows). This gradual expenditure also will allow the states to adapt to unforeseen circumstances over the next year.

State Fiscal Assistance Intended to Support Public Services and State Economies

Congress included state fiscal assistance in ARRA for two reasons. One was that extensive evidence provided by economists and others made the case that helping states close their budget shortfalls was one of the best ways the federal government could strengthen the national economy. Each dollar of federal aid to states, according to Moody’s Economy.com, produces $1.36 in increased economic output — a far bigger “bang-for-the-buck” than most other forms of economic stimulus under consideration, including tax cuts.

The reasoning is straightforward. When states reduce spending, they lay off employees, cancel contracts with vendors, lower payments to businesses and nonprofits that provide services, and cut benefit payments to individuals. All of these steps lower aggregate demand in the economy, which worsens a downturn.

The second reason for state fiscal assistance in ARRA was the extent to which cuts in important services would harm residents and communities. Massive state budget shortfalls — almost certainly the largest since the Great Depression — already have led roughly three-fourths of the states to cut back on health care, assistance for seniors and people with disabilities, K-12 and higher education, and other services. With the economy worsening, revenues continuing to fall, and more Americans turning to local and state agencies for help, these shortfalls clearly were having dramatic human impacts.

ARRA’s two main streams of operating funds to states are:

- An estimated $87 billion in federal Medicaid funding. Under the recovery act, the federal government is paying a larger-than-normal share of the Medicaid expenses that states incur from the fourth quarter of 2008 through the end of 2010. The primary purpose of these funds is to address the rising Medicaid costs that come as more people lose employer-provided coverage and qualify for Medicaid.

- A new $48 billion State Fiscal Stabilization Fund administered by the federal Department of Education. Of this amount, $39.5 billion is to be used for ongoing operating support to public schools, colleges, and universities, mostly replacing state aid that otherwise would likely be cut due to insufficient revenues. The remaining $8.8 billion is in a flexible block grant that states can use to support general government services.

The recovery act also contains smaller funding sources for states — some of which can help solve their budget problems. Examples include Byrne Grant law enforcement block grants, child care block grants, and grants through the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program. Under some circumstances, states may use these funds to pay for services they otherwise would have cut, helping addressing their budget shortfalls.

Other major streams of funding in the recovery act that flow through state governments cannot be used to address state operating budget shortfalls. Some are specifically targeted for programs that generally lie outside of the operating budget, such as transportation and unemployment insurance. Others are designed to be passed on to local governments.

States’ Use of ARRA Funds to Balance Their Budgets

As states resolve lingering budget problems from the current fiscal year (2009) and enact new budgets for fiscal year 2010 — which in most states begins July 1 — most are using a combination of federal relief, cuts in spending, revenue increases, and such other measures as drawing down reserve funds to balance their budgets.

Although it is still too early to have a complete picture of how the funds are affecting every state’s budget, all evidence to date suggests that the money is making a substantial difference. Without the funds, the extent of budget cuts undoubtedly would be greater. A handful of concrete examples:

- The Alabama Department of Human Resources avoided cutting 3,000 subsidized child care slots; the state also saved an estimated 3,800 education jobs and kept most agencies at or near level funding in Fiscal Year 2010 instead of facing cuts.

- Arizona used $20 million to reverse cuts to child care subsidies for low-income families. The cuts were scheduled to take effect this spring and ultimately would have affected 20,000 children.

- California reversed a requirement that Medi-Cal (Medicaid) beneficiaries renew their eligibility more frequently, which was expected to cause large numbers of children to lose coverage.

- Georgia amended its budget for Fiscal Year 2009 to use $145 million in federal funds to replace funding that school districts were scheduled to lose. Overall, in its 2009 and 2010 budgets, Georgia is using federal funds to close 36 percent [1] of its projected budget gap; the rest is being closed with spending cuts, a cigarette tax increase and other budget measures.

- Maryland used $2.5 billion to help balance the state’s budget in fiscal years 2009 and 2010. The money helped reverse a number of cuts the governor had proposed to K-12 public schools and community colleges, avoid 700 proposed layoffs, and fund anticipated cost growth in the state’s Medicaid and energy assistance programs, among other measures. Overall, the federal funds are offsetting 38 percent of the state’s projected 2009 and 2010 budget gaps.[2]

- New York passed a fiscal year 2010 budget that uses $4.9 billion to help close the state’s budget shortfall and mitigate Governor Paterson’s proposed cuts to K-12 and higher education, health and human services funding, and state municipal aid; the impact in New York is described further below.

- In Oklahoma federal aid filled in for an unexpected decline in revenues. Among other impacts, the aid allowed universities to avoid raising tuition for next year.

- In order to qualify for the enhanced level of federal Medicaid assistance under the new federal law, South Carolina reversed previously made cuts that had restricted eligibility and access to Medicaid services. Most notably, the state will not impose tighter income requirements that would have resulted in loss of coverage for an estimated 3,700 elderly and disabled persons.

- Utah used federal assistance to mitigate cuts to K-12 and higher education, among other areas.

- Virginia enacted a revised two-year (2009 and 2010) budget that uses federal stimulus aid to mitigate previously proposed cuts to health care, K-12 and higher education, and the state government workforce. Virginia impacts are described further below.

- In Washington, federal aid is being used to avert or mitigate cuts to funding for property-poor school districts, cuts to funding for educational quality improvements such as class size reduction, early learning and professional development, and cuts to higher education funding. It is also being used to lessen cuts to public safety and rehabilitation programs. The Senate Ways and Means Committee reports that federal funds reduced the size of the state’s budget gap by one-third.

A Closer Look at New York and Virginia

New York and Virginia provide useful case studies of the recovery act’s impact on state budgets, for several reasons. Their projected budget shortfalls in the latter part of 2008 and early 2009 were very large relative to the size of their budgets. (New York’s was one of the nation’s largest.) Their governors’ proposed budgets, issued before Congress enacted ARRA, provide a useful snapshot of what the states might have done in the absence of the recovery act dollars. And, because they were among the first states to enact new budgets in the spring of 2009, detailed information is available showing how ARRA funds affected the budget process. In both Virginia and New York, recovery act funding is important to closing budget gaps, but it is only part of the solution.

Virginia: Recovery Funds Closing 37 Percent of Budget Shortfall

The recession opened a wide hole in Virginia’s budget by shrinking state revenues. When enacted in June 2008, the budget for the 2009-10 biennium (i.e., the two-year period ending June 30, 2010) was in balance. But subsequent estimates showed that the state was unlikely to collect enough revenue to cover budgeted spending. By February 2009, the gap between projected revenues and expenditures had risen to $4 billion. At roughly 13 percent of the budget, the shortfall was somewhat below the national average but still sizable and difficult to close.

Virginia enacted a revised budget for 2009-10 just a few weeks after passage of the federal recovery act. The updated plan reflects the state’s decision to use $962 million in new federal Medicaid funding, $491 million from the education portion of the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund, and $24 million in Byrne Grant funds for law enforcement.

Virginia is closing the remainder of its budget gap with a combination of spending reductions, small revenue increases, and drawing down the state’s reserve fund (see Figure 1). Even with the recovery act funding, the state has cut spending substantially: the revised budget is 8 percent below the original budget for 2009-2010 and approximately 7.6 percent below the budget for 2007-2008, despite rising costs and caseloads.

Virginia plans to use approximately 71 percent of the federal Medicaid funding it expects to receive over the lifetime of the recovery act, as well as 50 percent of the education stabilization funding and about 60 percent of its Byrne Grant funding, during the 2009-2010 biennium. Most likely it will use the remainder of the recovery act funds in the next budget period (which begins July 1, 2010), although the state could use some of these funds sooner if budget conditions deteriorate further.

New York: Recovery Funds Closing 31 Percent of Budget Shortfall

Prior to ARRA’s enactment, New York faced an even more precarious fiscal situation than Virginia. The crisis in the nation’s financial services industry — highly important to the state’s revenue base — and the broader economic downturn led revenues to decline sharply. New York predicted that without changes to its revenue structure or spending programs, available funds in fiscal year 2010 (the 12-month period beginning April 1, 2009) would fall about $17.9 billion or 26 percent short of what was needed to balance the budget. In addition, New York’s FY2009 budget was projected to be short $2.2 billion due to declining revenues and rising costs.[3]

The federal recovery law is providing New York $6.2 billion in federal funding that it is using to help close its budget gap. This includes $5 billion in additional federal Medicaid funding, $876 million in education-related State Fiscal Stabilization Fund money, and $274 million from the “government services” component of the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund.

To put these numbers in perspective, across two fiscal years (2009 and 2010) federal recovery assistance is closing roughly 31 percent of New York’s budget hole. A major tax increase will cover about 27 percent of the shortfall, spending reductions another 32 percent, and such one-time budget maneuvers as fund transfers the remaining 10 percent (see Figure 2).[4]

As in Virginia, New York is not planning to use all of its available recovery act funding by the end of fiscal year 2010, instead reserving some for 2011 as the law allows. The state plans to use approximately 60 percent of its increased Medicaid funding, 36 percent of education stabilization funding, and 50 percent of government services stabilization funding in fiscal years 2009 and 2010.

Recovery Act Averting Cuts in Important Services

Virginia: Reversing Proposed Cuts in Health, Education and Public Safety

When Governor Kaine proposed a revised budget for 2009 and 2010, he did not take federal recovery act funding into account because the legislation was far from certain. Instead, he proposed deep spending cuts. A comparison of the governor’s proposal with the budget he eventually signed in March 2009 — which did reflect the recovery act — suggests the kinds of cuts the legislation allowed the state to avoid. The federal funds:

- Enabled the state to retain its funding for some 13,000 non-teaching school personnel — such as janitors, psychologists, and administrative assistants — that the governor had proposed eliminating. The proposed $341 million cut for local school districts (relative to previously budgeted levels) would have placed additional stress on already strained school district budgets.[5]

- Allowed the state to reduce its planned cut to state colleges and universities from $296 million to approximately $169 million (not taking into account other smaller changes enacted by the legislature), lessening the need for tuition increases. For example, following release of the governor’s budget proposal, the president of Virginia Tech said the university would need to raise tuition by 9 percent, on top of an 11 percent increase implemented in the fall of 2008.[6] Ultimately, with the help of federal stimulus aid, Virginia Tech held its tuition increase for the coming academic year to 5 percent. [7]

- Prevented closure of three hospitals and treatment centers serving persons with mental health needs. Closing these facilities would have entirely eliminated Virginia’s public inpatient psychiatric services for children. This raised concerns that the 844 children and adolescents served there might have trouble finding alternative sources of treatment. Opponents of the closures feared that private hospitals might be unable or unwilling to care for the patients with the most severe disabilities. They also raised concerns that some of these patients might end up in juvenile detention facilities for lack of available alternatives.

- Enabled the state to provide 200 mentally disabled individuals with care outside of an institutional setting. This funding, which was eliminated in the governor’s proposed budget revisions, means that recipients can reside outside of a mental health institution while receiving intensive treatment (such as skilled nursing services) that they would not otherwise be able to afford. More than 4,200 people are on a waiting list for this funding, according to the Department of Mental Health.

- Prevented a 3 percent cut in inpatient hospital reimbursement rates relative to previously budgeted levels. The proposed cut would have reduced revenue to the state’s nonprofit hospitals at a time when many are likely to face budget problems of their own — potentially leading to staff layoffs or cutbacks in patient care.

- Averted a proposed cut in aid to local sheriffs’ departments. The Virginia Sheriffs’ Association had warned that the cut would have forced the elimination of 310 deputy sheriffs’ positions.

The legislature likely would have approved the governor’s proposed cuts had recovery act funding not been available. In fact, there is good reason to think it would have gone even further. Between December 2008 (when the governor outlined his proposals) and March 2009, the Virginia revenue forecast was revised downward even further by over $800 million. The legislature also rejected the governor’s proposal to raise the cigarette tax. Thus, the federal recovery funding helped to avert not only the governor’s proposed cuts, but also the additional cuts that would have resulted from the further decline in the revenue forecast and the legislature’s decision not to raise the cigarette tax.

New York: Reversing Proposed Cuts to Education, Other Core Services

Governor Paterson, like his counterpart in Virginia, issued his budget proposal in December 2008, before the recovery act was enacted, so it did not reflect the additional federal dollars. As in Virginia, a comparison of the proposed December budget with the final budget signed in March suggests the impact of the recovery act funds. The funds:

- Contributed $750 million to pay for anticipated increases in Medicaid costs in fiscal years 2009 and 2010. The state’s Medicaid enrollment is projected to grow by 3.7 percent between fiscal years 2008 and 2009 and 7.9 percent between 2009 and 2010. (Medicaid is a countercyclical program, designed so rolls can increase during economic downturns when people lose jobs, health insurance, and income.) The state had not anticipated such levels of increase at the time the governor submitted his original budget.

- Averted $1 billion in planned health care cuts. The governor had proposed deep cuts to state reimbursements for hospitals and nursing homes that serve Medicaid patients. He also had proposed eliminating state funding to help seniors with limited incomes to purchase drugs that Medicare Part D does not cover.

- Allowed the state to reduce its share of spending on health care relative to the federal share and use the resulting savings to fill holes in other areas of the budget. By this means, New York reduced by $1.3 billion the revenue increases the governor had advocated for fiscal year 2010. These included proposed taxes on non-diet soft drinks and digital downloads, as well as the imposition of sales taxes on an array of items.

- Prevented several proposed cuts to human services, mental health, and other programs. Using $164 million of the added federal Medicaid funds, New York is cancelling several proposed reductions in human services and related areas. These included planned cuts of between $16 and $28 in monthly Supplementary Security Income (SSI) payments to low-income residents who are elderly, blind, or have disabilities.

- Averted the proposed elimination of $328 million in aid for New York City. New York City is facing its own considerable fiscal challenges, and Mayor Bloomberg recently released an austere budget proposal that includes more than 3,700 layoffs. [8] The elimination of state municipal aid would likely have resulted in further layoffs and program cuts.

- Reversed a sweeping cut to K-12 education aid for the 2009-2010 school year. Governor Paterson had called for a $1.1 billion reduction in state K-12 education aid. Faced with declining state revenues and growing expenses, school districts would have had little choice but to cut positions, salaries, and programs or raise property taxes more than they already are. The federal recovery funds allowed New York to undo the proposed cut.[9]

- Averted proposed cuts to community college funding. New York used $39 million in education stabilization aid to avoid the cuts, reducing the need for tuition increases and program and staff cuts.

- Helped the state avoid a number of the governor’s other proposed cuts, primarily in K-12 and higher education. The “government services” stabilization funding in the recovery act enabled the state to avoid proposals to shift some pre-school special education costs to local school districts and to cut professional development resources for teachers.

- Averted proposed eligibility restrictions for a college tuition assistance program for low- and moderate-income New York residents. The program helps these students afford in-state colleges or universities.

As in Virginia, most or all of the governor’s proposed cuts would likely have become law had it not been for the federal funding. Like Virginia, New York received new revenue estimates in early 2009 indicating the 2009 and 2010 budget gaps were even worse than the governor’s budget had assumed, meaning that his proposals — severe as they were — would have been insufficient to balance the budget. As it happened, the federal recovery funds helped to avert not only many of the governor’s proposed cuts, but also likely additional cuts.

Conclusion

As the first state fiscal year to be seriously affected by the current devastating national recession ends and a new one — with even greater challenges anticipated — begins, federal fiscal assistance for state governments clearly is having the intended impact. Though deep cuts in vital services and programs cannot be avoided entirely, ARRA assistance has enabled states to close their large budget shortfalls with smaller cuts in education, health care, and other important services than would have occurred otherwise. This has lessened both the hardship faced by the most vulnerable residents and the damage to state economies that comes when states sharply reduce spending in a recession. Federal assistance has helped change the state budget equation for the better.

End Notes

[1] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities calculation using Georgia Budget and Policy Institute data.

[2] Maryland Budget and Tax Policy Institute.

[3] The state budget is defined here as the state’s general fund plus funding for the health care reform act, which is a separate component of the state’s budget. These figures exclude federal aid.

[4] CBPP analysis of New York State Division of Budget data. The budget gap that existed prior to the federal recovery legislation and prior to enactment of the budget bill reflects the gap between projected revenues and the cost of providing current-law services. The cost of services thus reflects such items as rising need for state-financed health care programs and other rising cost factors.

[5] Specifically, the governor proposed cutting a state program that reimburses school districts for a substantial share of the cost of employing key non-teaching personnel. Given Virginia school districts’ own budget problems, it is likely that all or most of those positions would be eliminated without the state funds.

[6] Warren Fiske, “College Presidents: Tuition Will Increase With State Cuts,” The Virginian-Pilot, January 22, 2009.

[7] Larry Hincker, “Board of Visitors Sets Tuition and Fees for 2009-10,” Virginia Tech News, April 23, 2009.

[8] New York City Office of Management and Budget.

[9] The federal aid was insufficient, however, for the state to fully fund its foundation education formula, which had been enacted in 2007 to address a court decision that the state had failed to meet its legal obligation to ensure adequate education funding for all children.

More from the Authors