- Home

- Medicaid And CHIP Eligibility Is Protect...

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility Is Protected For Jobless Families That Receive Boost in Unemployment Benefits

An estimated 17.9 million jobless workers who become unemployed in 2009 will see their unemployment benefits increase by $25 per week under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA).[1] While unemployment benefits typically are included as income when determining eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP, ARRA excludes this additional $25 per week from the Medicaid and CHIP income eligibility calculations.[2] Congress provided for this income exclusion to ensure that the modest increase in unemployment benefits does not jeopardize a family’s Medicaid or CHIP eligibility.

By contrast, the $25 per week increase is counted in determining eligibility for food stamps (now called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP), as well as in determining the amount of food stamp benefits the family receives. Food stamp benefits phase down slowly with each additional dollar of earnings, so an additional $100 in income (including unemployment benefits) in a month results in a decline in food stamp benefits of roughly $30. In Medicaid and CHIP, however, individuals generally are either eligible for a full benefit package or they are wholly ineligible for coverage — benefits do not phase out as income rises. Thus, excluding $100 of additional income in a month can prevent a family or individual from becoming uninsured.

In other programs where states have broad flexibility to establish income-counting rules, such as TANF or child care, states can decide whether or not to exclude the additional unemployment benefits. In programs such as child care, where families lose significant benefits if their incomes go $1 above the income eligibility threshold, it is particularly important for states to consider excluding the additional $25 in unemployment benefits from the eligibility determination.[3]

States will need to adjust their eligibility determination procedures in Medicaid and CHIP — and in any other program in which they choose to disregard the additional unemployment benefits — to ensure that these additional benefits are excluded properly.

Safeguarding access to Medicaid and CHIP for jobless workers and their children is important. Many low-wage workers who lose their jobs did not have access to employer-sponsored health care coverage when they were working, and therefore do not have access to “COBRA” coverage — named after a law that allows unemployed workers to continue to participate in their former employer’s health plan at the worker’s expense. And, many workers who lose their jobs and also lose employer-sponsored health care coverage will be unable to afford “COBRA” coverage even with the new subsidy provided under ARRA. Public coverage, under Medicaid or CHIP, is often the only option for such families. The $25 per week exclusion will largely affect parents and children because unemployed adults who are not parents or do not have serious disabilities typically are ineligible for Medicaid (and CHIP) coverage, regardless of how poor they are.

States Can Decide How to Distribute the Additional Unemployment Benefits

Technically, ARRA gives states an option to provide the additional $25 per week in unemployment benefits to individuals who otherwise qualify for jobless benefits through the end of calendar year 2009. The additional benefits are financed entirely by the federal government and it appears that all states will provide these additional benefits to jobless workers.

ARRA gives states the flexibility to determine how they distribute the additional benefits. States may simply add the $25 per week to weekly unemployment insurance checks or they may issue a separate check for these additional benefits. Further, the method of payment may differ at the early stages of implementation than in later months. For example, Arizona has elected to provide the additional benefits effective mid-February, but the state must first program its computers to provide the additional benefits. Thus, initially, jobless workers may receive a lump- sum payment representing several weeks of the additional benefits and then begin receiving them on a weekly basis.

It is important for state agencies that determine eligibility for Medicaid, CHIP, and other benefits to contact their state unemployment insurance program, typically operated through a state’s labor department (though those departments have different names in different states), to learn when their state is planning to implement the benefit increase and how it intends to provide the benefits. States will then need to instruct eligibility workers on how to exclude these benefits when determining eligibility.

In a state that chooses to add the additional $25 to the weekly checks received by all unemployed workers receiving jobless benefits, eligibility workers may simply be able to deduct $25 per week from the jobless benefits that a family reports receiving. But, a state that provides the additional unemployment benefits in a separate check may need to instruct eligibility workers to ask families to clarify whether the amount of unemployment benefits they report represents their standard benefit or the sum of their standard benefit and the additional amount. States also will need to instruct eligibility workers on how to handle retroactive lump-sum payments that reflect the additional benefits for several weeks.

Excluding the Boost in Unemployment Benefits Will Help Parents and Children

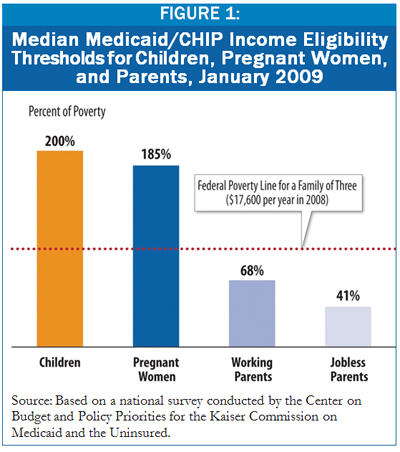

The income eligibility limits for children in state Medicaid and CHIP programs are often significantly higher than the eligibility limits for parents. For children, the median income eligibility level for Medicaid or CHIP is twice the federal poverty line. Many families in which a parent loses a job have incomes below this threshold, but modest increases in unemployment benefits could put them slightly above this threshold and leave their children without coverage.

To qualify for Medicaid coverage, a parent must have income well below the poverty line in most states. For employed parents, the eligibility limit in the median state is 68 percent of the poverty line. But for jobless parents, the Medicaid income limits are even lower; a family’s income must sink well below the federal poverty line — to less than half the poverty line in 29 states — before a parent can qualify.[4] In the median state, a parent must have income below just 41 percent of the federal poverty line — or about $600 per month for a family of three — to qualify for Medicaid. Many unemployed workers who receive unemployment benefits will have incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid in states with very low eligibility limits. But, some low-wage workers qualify for very low unemployment benefits and the exclusion of the $25 per week in additional benefits could make the difference between meeting the tight eligibility limits or exceeding them.

End Notes

[1] “Millions of Jobless Workers to Get Critical Aid in American Recovery and Reinvestment Act,” National Employment Law Project, February 14, 2009.

[2] Section 2002(h) of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

[3] In child care programs, copayment amounts typically rise as income rises, gradually reducing the subsidy the family receives. However, child care programs generally have an income-eligibility limit, as well; families with incomes close to this limit often receive significant child care subsidies despite the higher copayments they must pay as compared to families with lower incomes. Thus, the $25 per week in additional unemployment benefits could put a family over the income-eligibility threshold and result in the family losing eligibility for a significant child care subsidy.

[4] Donna Cohen Ross and Caryn Marks, “Challenges of Providing Health Coverage for Children and Parents in a Recession,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities for the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, January 2009.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work: