- Home

- House Budget Committee Plan Cuts Pell Gr...

House Budget Committee Plan Cuts Pell Grants Deeply, Reducing Access to Higher Education

The House Budget Committee budget plan calls for large cuts in Pell Grants, which help more than 8 million students from low- and modest-income families afford college. These are among the plan’s $5 trillion in cuts in non-defense programs, 69 percent of which would come from programs that help families with low or modest incomes.[1] The plan’s cuts in Pell Grants and other education programs would make it more difficult for these students to afford college at a time when those costs are rising quickly.

The plan freezes the maximum Pell Grant for ten years, even as tuition and room and board costs will continue to rise. It also eliminates Pell Grant funding on the mandatory side of the budget (Pell Grants receive both mandatory and discretionary funding, as explained below), likely forcing further cuts in eligibility and benefits. In addition, it would make student loans more expensive and cut other education and training programs (see box).

The plan justifies its Pell Grant cuts by raising questions about the program’s finances and impact on the cost of higher education. These claims, however, are without merit.

- Pell Grant costs aren’t rising rapidly. To be sure, Pell Grant costs rose substantially between 2007 and 2010, largely as a result of the recession, which depressed family incomes and led more people to pursue college in order to improve their education and skills. In addition, Congress approved modest expansions of Pell benefits. But total Pell costs fell by roughly one-fifth between 2010 and 2015, adjusted for inflation, as the economy recovered and Congress pared back eligibility and benefits somewhat. Costs are projected to decline by 0.5 percent a year on average over the next decade, adjusted for inflation, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

- The Pell Grant program does not face an imminent or dire funding shortfall. CBO projects that appropriations will be adequate for at least the next two years if they grow no faster than the 2011 Budget Control Act’s (BCA) overall caps. After that, appropriations would need to be above that level by less than $1 billion a year on average. Rather, it is the House budget that would create a major funding shortfall for the Pell Grant program by eliminating all of its mandatory funding.

- Significant research shows that need-based grant aid, such as Pell Grants, enables more low- and moderate-income students to attend and complete college.[2] In contrast, the evidence that Pell Grants drive up college costs is weak.

The House Budget Committee plan’s harsh Pell cuts would add another significant barrier to educational attainment for low-income students — a group with disproportionately low rates of college attendance and graduation. Also, it would likely increase their debt burden. Pell Grant recipients are already more than twice as likely to have loans as other students, and the average debt burden for Pell recipients who graduate from four-year colleges is $4,750 higher than their higher-income peers.[3] In short, the House Budget Committee plan would reduce opportunity for low-income students striving to obtain a college education and a better future. It would also undermine a crucial investment in the nation’s future competitiveness and economic vitality. (The Senate Budget Committee’s plan also contains significant cuts to Pell Grant funding, but the size and nature of those cuts are left entirely unspecified.)

Background

Pell Grants are funded on both the discretionary and mandatory sides of the budget. Under current law, the maximum grant — $5,775 per student per year for the 2015-2016 school year — is scheduled to rise with inflation to roughly $6,000 by 2017 but then remain frozen at that level. Only students from families with low or modest incomes receive Pell Grants. Students who qualify for Pell Grants but have income in the higher part of the Pell income eligibility range, and students attending college part-time or with lower college costs, receive less than the maximum grant.

Discretionary funding, provided through the annual appropriations process, supports the first $4,860 of the maximum Pell Grant; mandatory funding, provided through past authorizing legislation, funds the rest. Policymakers have also provided additional funding (technically classified as mandatory) in recent years to supplement the regular annual Pell Grant appropriation, particularly to help cover costs related to participation increases during the recession and to the benefit expansions. Policymakers have mostly paid for this additional mandatory funding with savings generated by changes to student loan programs and to the Pell Grant program itself.

House Budget Committee Plan Cuts Funding and Limits Eligibility

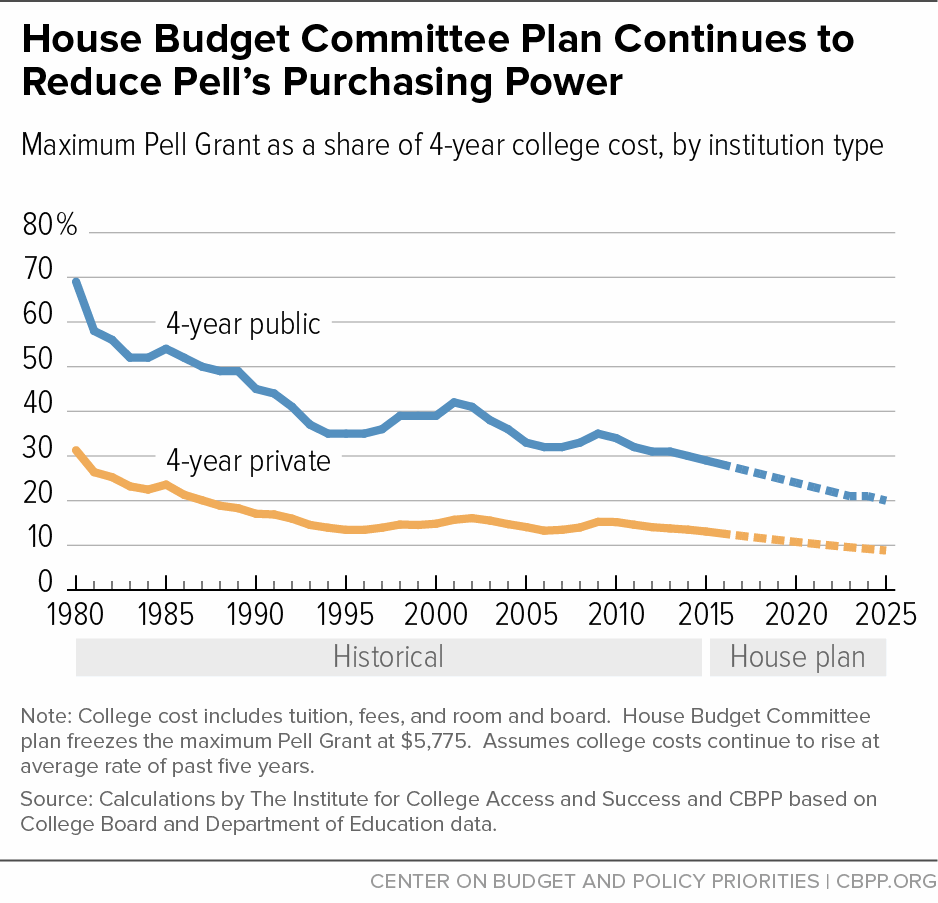

The House Budget Committee plan freezes the maximum Pell Grant at $5,775 for ten years. The purchasing power of Pell Grants has fallen considerably over time — the maximum grant now covers about 30 percent of the average cost of attending a four-year public college, the lowest share in 40 years and less than half what it covered in 1980 — and would continue to fall under the plan (see Figure 1).

The House Budget Committee plan also entirely eliminates mandatory funding for Pell Grants — about $90 billion over 2016-2025 — so all Pell funding would have to come through the annual appropriations process. But the budget provides no additional funding for discretionary programs in 2016 beyond the austere sequestration caps — and, starting in 2017, it sharply cuts funding for the non-defense discretionary (NDD) budget category below the sequestration levels; between 2017 and 2025, it would cut NDD programs by $759 billion below those levels. By 2025, NDD funding would be about one-third below the 2010 level, adjusted for inflation.

Within these severe constraints, it would be virtually impossible for Pell Grants to receive sufficient funding to maintain current eligibility rules, even at the frozen grant levels the budget proposes. NDD programs also include important investments in research, infrastructure, and other education programs, such as Title I, special education, and Impact Aid. They include a range of essential services, as well, from veterans’ medical care to border security to environmental protection. Fully funding Pell Grants would require even steeper cuts in these other programs than they would already face under the House budget. More likely, policymakers — facing competing demands and severely reduced NDD funding — would sharply restrict Pell eligibility or cut benefits even more (or both) to meet the terms of the House Budget Committee plan.

Pell Costs Have Fallen Considerably Since Recession

The House Budget Committee plan argues that the Pell Grant program “is now facing a shortfall” and implies that its finances are unsustainable. But in reality, Pell costs have fallen significantly in the past few years. Total Pell Grant costs fell by about one-fifth from 2010 to 2015 (adjusted for inflation).

During the Great Recession, falling incomes made more families eligible for this means-tested program, while a number of people who lost their jobs went back to school to gain new skills.[4] In addition, Congress approved on a bipartisan basis modest expansions to encourage more low-income students to get a college degree, as well as increases in the maximum Pell Grant award that offset only a small part of the grant’s long-term decline in purchasing power.

With the economy recovering, the number of eligible students has declined. Further, Congress reduced eligibility and benefits in 2011 and 2012, including reversing some of the changes it had recently enacted, reducing Pell costs by more than $50 billion over ten years.[5] Over the past several years, CBO has consistently revised downward its estimates of Pell Grant program costs, and it now projects that total program costs will decline by 0.5 percent a year on average over the next decade, adjusted for inflation. Even if the maximum Pell Grant award were indexed to inflation after 2017, as the President proposes, total program costs would rise only about 1.5 percent faster than inflation each year, on average, over the next decade.[6]

As a result, the program has no immediate shortfall. With funding carried over from prior years, the program is expected to have adequate funding through 2017. The program’s funding gap thereafter totals about $6 billion through 2025, assuming Pell Grant discretionary funding rises with the nominal growth in the BCA caps. This will require supplemental funding in a difficult funding environment, but the program clearly is not in crisis.

Research Shows Pell Grants Improve College Access

Research shows that Pell Grants and other need-based aid help students attend and graduate from college. Students qualifying for Pell Grants are more likely than other students to face significant hurdles to completing college, such as single parenthood and lack of financial support from their own parents. Controlling for these risk factors, a Department of Education study found that Pell Grant recipients who get their degrees do so faster than other students.[7] Further, research on need-based grant aid more generally has shown that such aid increases college enrollment among low- and moderate-income students.[8]

The House budget criticizes federal student aid as a system that “enables skyrocketing tuition,” linking Pell Grants and other student aid to increases in college costs in recent years. House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Paul Ryan made similar claims last year, asserting that Pell Grants actually hurt students from low- and moderate-income families.[9] But the evidence for this hypothesis is extremely shaky. A Congressional Research Service review of the studies on this issue found that “the body of research on the relationship between federal financial aid and college prices does not provide conclusive results in any direction.”[10]

In short, the House Budget Committee’s Pell Grant cuts, as well as its damaging cuts to other education programs, would reduce opportunity for students from modest backgrounds who are striving for a college education and a better future. While the House plan claims to be making Pell Grants “permanently sustainable,” it really means sharp cuts in funding and eligibility, resulting in fewer low-income students able to afford college and, as a result, likely reductions over time in economic opportunity and the readiness of the U.S. workforce.

Budget Plan Contains Other Damaging Cuts to Education Funding

The House Budget Committee budget plan calls for cutting mandatory programs in the budget category that includes higher education funding by $180 billion over ten years. To meet this goal, Congress would likely have to eliminate most or all mandatory funding in this category — which helps low-income students afford college through Pell Grants and provides services for very vulnerable children and families, among other uses — and raise student loan payments significantly.

Specifically, the programs in this budget category include federal student loans, the mandatory portion of Pell Grants, vocational education, the Social Services Block Grant, the refundable part of the American Opportunity Tax Credit (which also helps students cover college costs), and more.

Eliminating mandatory Pell funding would save about $90 billion over ten years, leaving roughly $90 billion of additional savings to be achieved in this part of the budget. The budget documents do not specify where these additional savings would come from. But during the House Budget Committee’s consideration of the plan, committee staff indicated that the plan would eliminate in-school subsidies for undergraduate Stafford student loans (through which the government pays the interest on these loans while the student is in school), the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program (which eliminates any remaining student debt for former students who have ten years of full-time employment in public service and have made 120 qualifying payments on those loans), and a recent expansion of the Income-Based Repayment program (which caps monthly student loan payments as a share of borrowers’ income). According to the staff, the budget would also eliminate the Social Services Block Grant.

In addition, the House Budget Committee plan almost certainly includes cuts to education programs funded by discretionary appropriations. The budget cuts non-defense discretionary (NDD) funding between 2017 and 2015 by $759 billion below the already austere levels required by the Budget Control Act caps, as further reduced by sequestration. By 2025, NDD funding would be about one-third below the 2010 level, adjusted for inflation. With such deep cuts required, reductions would likely be unavoidable in discretionary education programs, which include Title I grants to states, special education grants, and Impact Aid, as well as Head Start and job training programs.

It is worth noting that the proposed House budget cuts to federal education funding would come at the same time that most states have significantly cut their higher education funding, including state grant support, and increased tuition at public colleges and universities.a

a For more on state cuts to higher education funding, see Michael Mitchell, Vincent Palacios, and Michael Leachman, “States Are Still Funding Higher Education Below Pre-Recession Levels,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 1, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4135.

End notes:

[1] Richard Kogan and Isaac Shapiro, “Congressional Budget Plans Get Two-Thirds of Cuts From Programs for People With Low or Moderate Incomes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 23, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=5289.

[2] The Institute for College Access and Success, “Pell Grants Help Keep College Affordable for Millions of Americans,” March 13, 2015, http://www.ticas.org/files/pub/Overall_Pell_one-pager.pdf.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Department of Education, “Student Financial Assistance: Fiscal Year 2012 Budget Request,” February 14, 2011, http://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/budget/budget12/justifications/p-sfa.pdf.

[5] CBPP calculations based on data from CBO, March 2011 baseline and estimates of changes made in 2011. Calculations based on changes in Pell Grant program costs during the period 2012 through 2021.

[6] Office of Management and Budget, “Fiscal Year 2016 Budget of the U.S. Government,” February 2, 2015, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Overview.

[7] Christina Chang Wei, Laura Horn, and Thomas Weko, “A Profile of Successful Pell Grant Recipients: Time to Bachelor’s Degree and Early Graduate School Enrollment,” National Center for Education Statistics, July 2009, http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2009/2009156.pdf.

[8] See Susan Dynarski and Judith Scott-Clayton, “Financial Aid Policy: Lessons from Research,” The Future of Children, Spring 2013, http://futureofchildren.org/futureofchildren/publications/docs/23_01_04.pdf.

[9] House Budget Committee majority staff, “The War on Poverty: 50 Years Later,” March 3, 2014, http://budget.house.gov/uploadedfiles/war_on_poverty.pdf.

[10] Adam Stoll, David H. Bradley, and Shannon M. Mahan, “Overview of the Relationship between Federal Student Aid and Increases in College Prices,” Congressional Research Service, August 22, 2014. While there is some evidence that for-profit institutions raise their prices in response to Pell Grants, there is very little evidence that public colleges and universities do substantially.

More from the Authors