- Home

- An Analysis Of Using "Progressive Price ...

An Analysis of Using "Progressive Price Indexing" To Set Social Security Benefits

In his news conference on April 28, President Bush embraced a Social Security benefit reduction plan that is consistent with a proposal advanced by Robert Pozen, a former vice chairman of Fidelity Investments and a member of President Bush’s Social Security Commission. Pozenhas developed a change in the Social Security benefit structure that he refers to as “progressive price indexing.”[1] Senators Lindsey Graham and Robert Bennett, among others, have indicated they are considering including this proposal in Social Security plans they are developing.

Under the proposal, low-earners would continue to receive the Social Security benefits promised under current law, which are based on a formula that uses “wage indexing,” while high-earners would have their benefits calculated under a formula that uses “price indexing” instead, with the result that their benefits would be reduced. (The benefit reductions would be phased in and would grow over time.) For average workers, benefits would be calculated by using a mix of wage indexing and price indexing; their benefits would be reduced but by a smaller percentage than benefits for higher earners.

This paper analyzes “progressive price indexing.” It contains five significant findings:

- Progressive price indexing would impose substantial benefit reductions on average workers. Progressive price indexing would reduce annual benefits for an average wage-earner who is 25 today and retires in 2045 by 16 percent or $3,523 (in inflation-adjusted 2005 dollars), relative to the benefits that the worker would receive under the current benefit structure. For an average-earner who retires in 2075, the benefit reduction would be 28 percent or $7,629 in today’s dollars. These are much larger benefit reductions than those included in alternative plans that achieve sustainable Social Security solvency through a mix of revenue increases and benefit reductions (as the 1983 Social Security legislation did).

- Progressive price indexing would use benefit reductions to close about 70 percent of the 75-year shortfall. The Social Security Trustees projected in March 2004 that the Social Security system has a deficit of 1.89 percent of taxable payroll over the next 75 years.[2] According to an analysis of the Pozen proposal recently conducted by the Social Security actuaries, progressive price indexing would reduce the deficit by 1.36 percent of taxable payroll and thus close 72 percent of the shortfall. (The remaining deficit would have to be closed by additional benefit reductions, tax increases or general revenue transfers.)

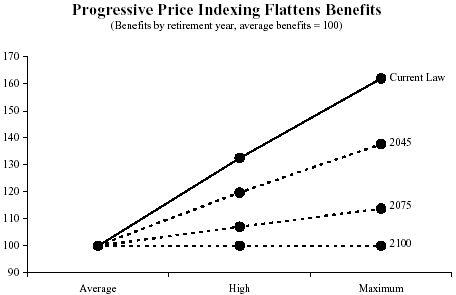

- Progressive price indexing would transform Social Security over time to a program that provides a modest retirement benefit largely unrelated to income. Because progressive price indexing produces very large reductions in benefits over time for high earners, substantial benefit reductions for average earners, and no reductions for low earners, it eventually eliminates most differences in benefit levels. Ultimately, most beneficiaries would get the same monthly benefit, despite having paid in very different amounts in payroll taxes.

Under current law, “high earners” (those whose earnings are 60 percent above the earnings of the average earner) receive Social Security benefits that are 33 percent higher than the benefits that average earners get. Under progressive price indexing, this difference would shrink to only 7 percent for workers retiring in 2075, and the difference would be eliminated entirely by 2100. This raises the question of whether broad political support for Social Security can be sustained if workers pay very different amounts of payroll taxes but most workers receive the same level of benefits. - Combining progressive price indexing with private accounts carved out of Social Security would make the system unattractive to high-earners. Making Social Security’s benefit formula this progressive could risk undermining some of the broad-based political support that Social Security enjoys. If progressive price indexing is combined with “carve-out” private accounts, and Social Security benefits are reduced further for those who elect the accounts, the problem could become severe. Low earners would rely primarily on traditional Social Security benefits, while higher earners would receive only a tiny Social Security benefit or no Social Security benefit at all and would rely mainly on their private accounts.

- Progressive price indexing is poorly designed to respond to contingencies; the benefit reductions it engenders would grow deeper if the economy performed well, even though the Social Security shortfall would have narrowed on its own, and would grow smaller if the economy performed poorly and the Social Security deficit widened. The stronger that economic growth and real wage growth were, the bigger the benefit reductions would become under progressive price indexing. This would be a perverse effect; stronger growth would lessen Social Security’s financing problems and lower the amount of benefit cuts needed. Conversely, if economic growth slowed, the benefit reductions that progressive price indexing delivered would decrease in size even as the Social Security shortfall widened.

How Progressive Price Indexing Would Work

Under current law, initial Social Security benefits for each generation of retirees grow in tandem with average wages in the economy. This ensures that each generation receives Social Security benefits that reflect the living standards of its times. Full “price indexing” would make a change in the Social Security benefit formula so that initial Social Security benefits would keep pace only with prices, rather than wages, from one generation to the next. Because prices increase more slowly than wages, this would result in progressively larger benefit reductions over time.[3] The latest estimates by the Social Security actuaries show that full price indexing would cut benefits by 29 percent for people retiring in 2045, growing to a 49 percent cut for people retiring in 2075, relative to the benefits scheduled under the current Social Security system.

The Pozen proposal would use price indexing to determine the benefits for “maximum earners,” people who currently make $90,000 or more annually. Lower-earners — specifically the bottom 30 percent of earners, or those who make less than about $20,000 currently — would continue to have their benefits calculated under the current formula. (Pozen describes the cutoffs as $25,000 but that is because he is using the expected threshold level in 2012 and expressing it in 2012 dollars.) Anyone whose annual earnings over his or her career averaged between $20,000 and $90,000 would get a benefit somewhere between the currently promised benefit and the benefit that would be provided under price indexing. For example, a worker making about $35,000 annually would be subject to about half of the price-indexing benefit reduction, while a worker making about $55,000 annually would be subject to more than 80 percent of the price-indexing benefit reduction.

Benefit Reductions for Average Workers

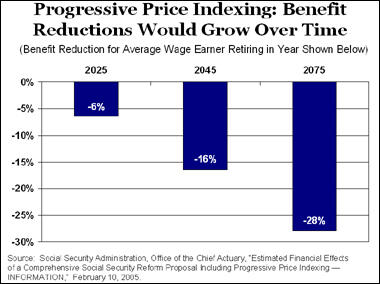

Estimates of Mr. Pozen’s plan made by the Social Security actuaries show that the plan’s benefit reductions (relative to the benefits scheduled under current law) would grow sharply over time.[4] These benefit cuts would grow from six percent for an average wage worker born in 1960 who retires in 2025, to 28 percent for an average-wage earner born in 2010 who retires in 2075. (See Figure.)

An average worker aged 25 today who retires in 2045 would receive a reduction in Social Security benefits of $3,253 per year (in inflation-adjusted 2005 dollars). For an average worker retiring in 2075, the benefit reduction would be $7,629 per year. (See Table 1.) The Social Security benefit would replace 26 percent of pre-retirement income for the average wage-earner retiring in 2075, down from 36 percent under the current-law formula. These benefit reductions are nearly twice the size of the benefit reductions proposed in more balanced plans to achieve sustainable solvency, such as a plan proposed by MIT economist Peter Diamond and Brookings economist Peter Orszag.[5]

For a high-wage worker (someone making about $58,600 in 2005, or about 60 percent more than the average wage of $36,600 this year), the benefit reductions would grow from $6,444 for someone retiring in 2045 to $15,154 for someone retiring in 2075. For a maximum earner (someone who makes $90,000 or more in 2005), the benefit reductions would grow from $9,324 for an individual retiring in 2045 to $21,808 for someone retiring in 2075. The benefit reductions would be the same for workers whose annual earnings average $90,000 as for individuals who make many times that.

Progressive Price Indexing Would Close About 70 Percent of the 75-year Shortfall through Benefit Reductions

The Social Security Trustees project that the Social Security system has a deficit of 1.89 percent of taxable payroll over the next 75 years.[6] According to the Social Security actuaries, progressive price indexing would reduce the actuarial deficit by 1.36 percent of taxable payroll. This equals 72 percent of the shortfall. The remaining shortfall would have to be closed through additional benefit cuts, revenue increases, or borrowing.

Robert Pozen’s progressive price indexing proposal is part of an overall Social Security plan that Pozen has developed. In addition to including progressive price indexing, the Pozen plan specifies that the general fund of the U.S. Treasury shall automatically transfer money to Social Security in any year when the trust fund had a shortfall. (This provision, by itself, would guarantee sustainable solvency without any benefit cuts, tax increases, or private accounts.) The Social Security actuaries have estimated that this component of the Pozen plan would result in $1.9 trillion in general revenue transfers to Social Security over the next 75 years.[7] For his part, Senator Lindsey Graham is reportedly considering a plan that combines progressive price indexing with some form of increase in the payroll tax cap and possibly some borrowing as well.

| Table 1: | ||||||

| Current-law Formula | Proposal | Change | ||||

| Benefit | Replacement Rate | Benefit | Replacement Rate | Reduction | %Age Reduction | |

| Scaled Low Earner (45 percent of the average wage, or $16,470 in 2005) | ||||||

| 2025 | $9,718 | 49% | $9,718 | 49% | $0 | 0% |

| 2045 | 12,041 | 49% | 12,041 | 49% | 0 | 0% |

| 2075 | 16,599 | 49% | 16,599 | 49% | 0 | 0% |

| 2100 | 21,820 | 49% | 21,820 | 49% | 0 | 0% |

| Scaled Medium Earner (average wage, or $36,600 in 2005) | ||||||

| 2025 | 16,009 | 36% | 14,984 | 34% | -1,025 | -6% |

| 2045 | 19,837 | 36% | 16,584 | 30% | -3,253 | -16% |

| 2075 | 27,344 | 36% | 19,715 | 26% | -7,629 | -28% |

| 2100 | 35,945 | 36% | 22,428 | 23% | -13,518 | -38% |

| Scaled High Earner (160 percent of the average wage, or $58,560 in 2005) | ||||||

| 2025 | 21,228 | 30% | 19,190 | 27% | -2,038 | -10% |

| 2045 | 26,302 | 30% | 19,858 | 23% | -6,444 | -25% |

| 2075 | 36,254 | 30% | 21,100 | 18% | -15,154 | -42% |

| 2100 | 47,658 | 30% | 22,428 | 14% | -25,230 | -53% |

| Steady Maximum Earner (taxable maximum, or $90,000 in 2005) | ||||||

| 2025 | 25,929 | 24% | 22,999 | 21% | -2,930 | -11% |

| 2045 | 32,153 | 24% | 22,829 | 17% | -9,324 | -29% |

| 2075 | 44,236 | 24% | 22,428 | 12% | -21,808 | -49% |

| 2100 | 58,150 | 24% | 22,428 | 9% | -35,723 | -61% |

| Source: Authors calculations based on Social Security Administration, Office of the Chief Actuary, “Estimated Financial Effects of a Comprehensive Social Security Reform Proposal Including Progressive Price Indexing -- INFORMATION,” February 10, 2005 and Social Security Trustees, 2004 Annual Report. Note that all percentage reductions in benefits for 2025-2075 are taken directly from the actuaries’ memo. | ||||||

Under both such approaches, progressive price indexing would result in the bulk of the adjustments made to restore solvency coming through benefit reductions, rather than through a balanced mix of benefit reductions and revenue increases. A more balanced approach would not require benefit reductions of these magnitudes.

For example, the Diamond-Orszag plan would gradually raise the payroll tax cap from $90,000 to $105,000, impose a 3 percent “legacy charge” on income above the payroll tax cap, and modestly raise the payroll tax rate. It also includes several significant benefit reduction measures. A plan proposed by former Social Security Commissioner Robert Ball and introduced last fall by Rep. David Obey would raise the payroll tax cap gradually from $90,000 to $150,000 and preserve a scaled-back version of the estate tax, with the revenues from the estate tax dedicated to Social Security. The Ball plan includes benefit trims, as well. Such approaches would result in considerably smaller benefit reductions for average workers than the benefit cuts such workers would face under progressive price indexing. These approaches ask for somewhat larger sacrifices from higher-income households that have benefited handsomely from the generous tax cuts of recent years.

Progressive Price Indexing Would Transform Social Security to a Modest Retirement Benefit Largely Unrelated to Income

Progressive price indexing would result, over time, in a profound transformation of the Social Security system. By 2100, most Social Security beneficiaries would get exactly the same Social Security benefit, regardless of how much they earned or contributed to Social Security. (The top 70 percent of workers — those making about $20,000 in 2005 — all would receive an identical benefit; workers making less than about $20,000 would receive somewhat smaller benefits.) Progressive price indexing would lead to this result because it would reduce benefits the most for the top earners, reduce benefits less (but still substantially) for average earners, and maintain benefits for low earners.

The current Social Security benefit structure uses a complex formula to translate a worker’s earnings into the worker’s Social Security benefit. The more that a worker earns (up to the payroll tax cap) the higher the worker’s benefit is. The fact that there is a link between what a worker contributes in payroll taxes and the level of the benefit the worker ultimately receives has contributed to the widespread public support that Social Security enjoys.

The current-law benefit formula also is progressive. A high-wage worker makes 60 percent more than the average worker but receives a benefit 33 percent higher than what the average worker gets.

Under progressive price indexing, benefits for low-wage workers would continue to grow (in relation to inflation), while benefits for the top wage workers would be frozen in inflation-adjusted terms. The result would be a large compression in benefits.

- In 2045, a high-wage worker (a worker with earnings 60 percent above the earnings of average workers) would receive a benefit that was only 20 percent higher than the benefit the average worker received.

- In 2075, the high earner’s benefit would be just 7 percent higher.

- By 2100, if progressive price indexing continued, the majority of workers would get an identical Social Security benefit, $22,500 per year, regardless of the level of their earnings and payroll tax contributions.[8]

The graph below illustrates this trend. It shows the relative levels of Social Security benefits for average, high, and maximum earners under current law and compares them to the levels of Social Security benefits for these three types of earners in 2045, 2075, and 2100 under progressive price indexing.

Under the current benefit formula, Social Security benefits replace a sizeable fraction of pre-retirement income that ranges from 49 percent of pre-retirement income for low-wage workers to 24 percent for maximum earners. Under progressive price indexing, by 2100, the majority of workers would get $22,500 per year — replacing only 9 percent of pre-retirement income for a maximum earner.

Combining Progressive Price Indexing with Private Accounts Carved out of Social Security Would Make Social Security Less Attractive To High Earners

Any reform that makes Social Security more progressive must balance the benefits of a more progressive system against the risk of undermining the broad-based political support that helps sustain the nation’s most effective anti-poverty program. This tension would be exacerbated if progressive benefit reductions were combined with “carve-out” private accounts.

Private accounts carved out of Social Security would be financed by additional benefit reductions in Social Security for those electing the private accounts. These additional Social Security benefit reductions would make Social Security appear much less attractive than the private accounts. If progressive price indexing were included in a Social Security plan alongside carve-out private accounts, Social Security would become distinctly unattractive to higher-income families.

Table 2 shows the level of Social Security benefits under the current benefit structure, under progressive price indexing, and under progressive price indexing combined with carve-out private accounts. (The private accounts are assumed to include the Social Security benefit offset that President Bush and Robert Pozen have both proposed — namely, for each $1,000 in payroll tax contributions that a worker shifted from Social Security to a private account, the worker’s Social Security benefits would be reduced by $1,000, plus an interest rate equal to 3 percent above inflation.)

The table shows that with progressive price indexing and carve-out accounts, traditional Social Security benefits would decrease with income. Lower-income workers would be heavily reliant upon their Social Security benefits, while higher-income workers would get most or all of their retirement benefits from their private accounts.

With 4 percent accounts, as proposed by the President, the problem would become extreme. Maximum earners would not get any Social Security benefits by 2075. Moreover, with the private accounts being financed through offsetting reductions in Social Security benefits, this approach would make it appear as through maximum earners were contributing 8.4 percent of their wages to Social Security without getting any Social Security benefits.

Similarly, high earners would appear to be contributing 8.4 percent of their wages to Social Security and getting only a miniscule benefit in return. It is unlikely that such a system would be politically sustainable. (Paying for the private accounts through a “clawback” that came directly out of the private accounts rather than out of Social Security benefits could alleviate some of these concerns, but that is not how the President’s plan would operate.)

Progressive Price Indexing Is Not Well Designed; Benefit Reductions Would Become Larger If Social Security’s Finances Improved and Smaller If Social Security’s Finances Deteriorated

The magnitude of the benefit cuts that progressive price indexing would generate would depend on the rate of real wage growth. The faster that real wage growth was, the larger the benefit reductions would be.

For example, the Social Security actuaries project that real wage growth will average 1.1 percent annually. If real wage growth turns out to average 1.6 percent annually, the benefit cuts under progressive price indexing would be considerably larger than the benefit reductions described above. For example, under the Trustees’ assumptions of 1.1 percent real wage growth, an average-wage earner retiring in 2075 would get a 28 percent benefit reduction under progressive price indexing (relative to the benefits that would be provided under the current benefit structure). If real wage growth were 1.6 percent, this worker would be subject to a 35 percent benefit reduction.

Yet stronger real wage growth would reduceSocial Security’s imbalance (by increasing payroll tax revenues upfront and increasing benefit payments only with a considerable lag in time). The Social Security Trustees estimate that increasing real wage growth to 1.6 percent annually would eliminate nearly one-third of the 75-year shortfall. This means that if real wage growth were stronger in future decades than the Trustees currently project, progressive price indexing would result in deeper benefit cuts, even as the Social Security shortfall was getting smaller on its own.

Similarly, if real wage growth fell short of the 1.1 percent annual rate projected by the Trustees, the benefit reductions that progressive price indexing would generate would be smaller. But if real wage growth is lower, the Social Security shortfall will have increased in size.

As a result, even if one favors closing the Social Security shortfall primarily or entirely through benefit reductions, progressive price indexing would be a poor way to achieve robust, sustainable long-term balance. Changes in the benefit or tax structure under which benefits, payroll taxes or the normal retirement age are indexed to longevity would be much better at directly tying the size of the benefit or tax changes to the program’s solvency needs. Under such proposals, if average life expectancy proved to be longer than currently predicted (which would worsen solvency), benefit reductions or tax increases would kick automatically in to help alleviate the worsening of Social Security’s financial condition.

Conclusion

Progressive price indexing would represent a profound shift in Social Security. Ultimately, it would lead to most workers receiving the same Social Security benefit level, regardless of how much they had paid in payroll taxes.

If private accounts are added to the equation and are paid for by additional benefit reductions, the results become even more extreme. If progressive price indexing were combined with the President’s private accounts proposal, workers with average incomes of $90,000 or more would eventually receive no Social Security benefits at all. It is unlikely that a Social Security system structured in this manner would remain politically sustainable over time.

Progressive price indexing also would require substantially larger benefit reductions for middle-class workers than several alternative approaches to restoring solvency. This would be the case because with progressive price indexing, the onus of restoring sustainable solvency is placed primarily on benefit cuts, rather than on a more balanced mix of benefit reductions and progressive revenue-raising measures.

Even if one supports making benefit cuts the primary means of restoring solvency, progressive price indexing is not well designed to achieve that goal, since it would produce excessively large benefit reductions if the economy and real wage growth perform better than expected and insufficient savings if the economy performs more poorly than expected.

End Notes

[1] The White House fact sheet issued on April 28 (“Fact Sheet: Strengthening Social Security for Those in Need”) does not provide specific parameters but states that the President’s plan would adopt “a sliding-scale benefit formula, similar to the Pozen approach.” The fact sheet also states that the plan would close 70 percent of Social Security’s funding gap while protecting people with disabilities and introducing a new minimum benefit. These statements imply that the President’s plan solves only 57 percent of the 75-year solvency gap or else contains deeper reductions in Social Security retirement benefits than the Pozen plan. For more details, see Jason Furman, “How Would the President’s New Social Security Proposals Affect Middle-Class Workers and Social Security’s Solvency.”

[2] This is the standard measure of the Social Security shortfall. It implies that an immediate 1.89 percentage point increase in the payroll tax rate would close the 75-year Social Security shortfall.

[3] See Robert Greenstein, “So-called “Price Indexing” Proposal Would Result in Deep Reductions Over Time In Social Security Benefits,” January 28, 2005.

[4] Social Security Administration, Office of the Chief Actuary, “Estimated Financial Effects of a Comprehensive Social Security Reform Proposal Including Progressive Price Indexing -- INFORMATION,” February 10, 2005.

[5] Peter Diamond and Peter Orszag, Saving Social Security, Brookings Institution Press, 2003.

[6] Social Security Trustees, 2004 Annual Report.

[7] This figure is expressed in net present value, the equivalent the amount today that, with interest, would exactly cover these future costs.

[8] The Pozen plan is not clear about whether progressive indexing would continue after 2078. According to the description of the proposal by the Social Security actuaries, “The reductions under this provision [i.e., progressive price indexing] would continue through at least 2078 (the end of the current 75-year valuation period.) Reductions would be less in size thereafter if program financing is sufficient to fully pay scheduled benefits without further transfers of General Fund Revenue.”

More from the Authors