- Home

- States Likely Could Not Control Constitu...

States Likely Could Not Control Constitutional Convention on Balanced Budget Amendment or Other Issues

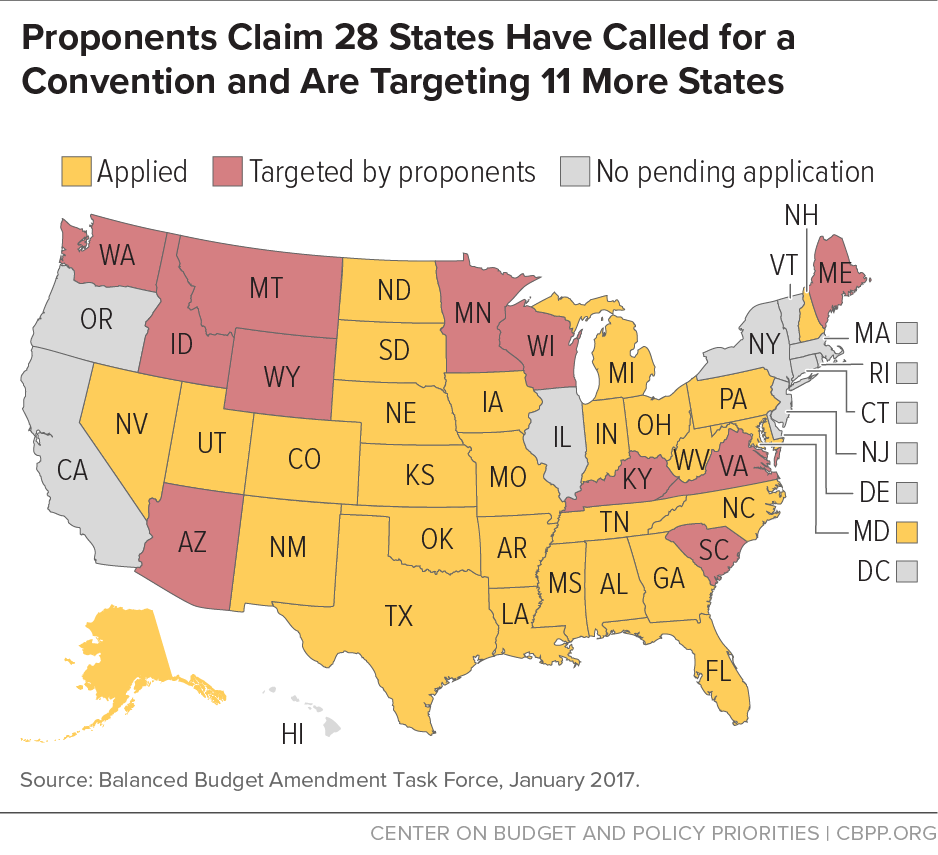

In the coming months, a number of states are likely to consider resolutions that call for a convention to propose amendments to the U.S. Constitution to require a balanced federal budget, and possibly to shrink federal authority in other, often unspecified, ways. Proponents of these resolutions claim that 28 of the 34 states required to call a constitutional convention already have passed such resolutions.

State lawmakers considering such resolutions should be skeptical of claims being made by groups promoting the resolutions (such as the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC) that states could control the actions or outcomes of a constitutional convention. A convention likely would be extremely contentious and highly politicized, and its results impossible to predict.

A number of prominent jurists and legal scholars have warned that a constitutional convention could open up the Constitution to radical and harmful changes. For instance, the late Justice Antonin Scalia said in 2014, “I certainly would not want a constitutional convention. Whoa! Who knows what would come out of it?”[2] Similarly, former Chief Justice of the United States Warren Burger wrote in 1988:

[T]here is no way to effectively limit or muzzle the actions of a Constitutional Convention. The Convention could make its own rules and set its own agenda. Congress might try to limit the Convention to one amendment or one issue, but there is no way to assure that the Convention would obey. After a Convention is convened, it will be too late to stop the Convention if we don’t like its agenda.[3]

Such serious concerns are justified, for several reasons:

- A convention could write its own rules. The Constitution provides no guidance whatsoever on the ground rules for a convention. This leaves wide open to political considerations and pressures such fundamental questions as how the delegates would be chosen, how many delegates each state would have, and whether a supermajority vote would be required to approve amendments. To illustrate the importance of these issues, consider that if every state had one vote in the convention and the convention could approve amendments with a simple majority vote, the 26 least populous states — which contain less than 18 percent of the nation’s people — could approve an amendment for ratification.

-

A convention could set its own agenda, possibly influenced by powerful interest groups. The only constitutional convention in U.S. history, in 1787, went far beyond its mandate. Charged with amending the Articles of Confederation to promote trade among the states, the convention instead wrote an entirely new governing document. A convention held today could set its own agenda, too. There is no guarantee that a convention could be limited to a particular set of issues, such as those related to balancing the federal budget.

As a result, powerful, well-funded interest groups would surely seek to influence the process and press for changes to the agenda, seeing a constitutional convention as an opportunity to enact major policy changes. As former Chief Justice Burger wrote, a “Constitutional Convention today would be a free-for-all for special interest groups.” Further, the broad language contained in many of the resolutions that states have passed recently might increase the likelihood of a convention enacting changes that are far more sweeping than many legislators supporting these resolutions envision.

- A convention could choose a new ratification process. The 1787 convention ignored the ratification process under which it was established and created a new process, lowering the number of states needed to approve the new Constitution and removing Congress from the approval process. The states then ignored the pre-existing ratification procedures and adopted the Constitution under the new ratification procedures that the convention proposed. Given these facts, it would be unwise to assume that ratification of the convention’s proposals would necessarily require the approval of 38 states, as the Constitution currently specifies. For example, a convention might remove the states from the approval process entirely and propose a national referendum instead. Or it could follow the example of the 1787 convention and lower the required fraction of the states needed to approve its proposals from three-quarters to two-thirds.

-

No other body, including the courts, has clear authority over a convention. The Constitution provides for no authority above that of a constitutional convention, so it is not clear that the courts — or any other institution — could intervene if a convention did not limit itself to the language of the state resolutions calling for a convention.

Article V contains no restrictions on the scope of constitutional amendments (other than those denying states equal representation in the Senate), and the courts generally leave such “political questions” to the elected branches. Moreover, delegates to the 1787 convention ignored their state legislatures’ instructions. Thus, the courts likely would not intervene in a dispute between a state and a delegate and, if they did, they likely would not back state efforts to constrain delegates given that delegates to the 1787 convention ignored their state legislatures’ instructions.

The following sections of this report provide background on the current campaign to call a constitutional convention and examine in more detail the reasons why policymakers should be skeptical of any claims that the states could control a constitutional convention. In addition, Box 1 below examines the substantial economic risks that a constitutional balanced budget amendment would pose.

Background: Campaigns for a Constitutional Convention

Article V of the Constitution provides for two methods of enacting constitutional amendments. Congress may, by a two-thirds vote in each chamber, propose a specific amendment; if at least three-fourths of the states (38 states) ratify it, the Constitution is amended. Alternatively, the states may call on Congress to form a constitutional convention to propose amendments. Congress must act on this call if at least two-thirds of the states (34 states) make the request. The convention would then propose constitutional amendments. Under the Constitution, such amendments would take effect if ratified by at least 38 states.

In part because the only constitutional convention in U.S. history — the one in 1787 that produced the current Constitution — went far beyond its mandate, Congress and the states have never called another one. Every amendment to the Constitution since 1787 has resulted from the first process: Congress has proposed specific amendments to the states, which have ratified them by the necessary three-quarters majority (or turned them down).

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, many states adopted resolutions calling for a constitutional convention to require the federal government to balance its budget every year. From the mid-1980s through 2010, no such new resolutions passed, and about half of the states that had adopted these resolutions rescinded them (in part due to fears that a convention, once called, could propose altering the Constitution in ways that the state resolutions did not envision).

Recently, though, additional states have called for such a convention, reflecting the efforts of a number of conservative advocacy organizations such as ALEC, which in 2011 released a handbook for state legislators that includes model state legislation calling for a constitutional convention.[4] Since 2010, 12 states have adopted such resolutions. According to some proponents of such a convention, a total of 28 states have now adopted resolutions (and not rescinded them). Proponents have targeted another 11 states for action this year and next.[5] (See Figure 1.)

Box 1: Balanced Budget Amendment Likely to Harm the Economy

Even if a constitutional convention could be limited to proposing a single amendment requiring the federal government to spend no more than it receives in a given year, such an amendment alone would likely do substantial damage.a It would threaten significant economic harm. It also would raise significant problems for the operation of Social Security and certain other key federal functions.

By requiring a balanced budget every year, no matter the state of the economy, such an amendment would risk tipping weak economies into recession and making recessions longer and deeper, causing very large job losses. Rather than allowing the “automatic stabilizers” of lower tax collections and higher unemployment and other benefits to cushion a weak economy, as they now do automatically, it would force policymakers to cut spending, raise taxes, or both when the economy turns down — the exact opposite of what sound economic policy would advise. Such actions would launch a vicious spiral: budget cuts or tax increases in a recession would cause the economy to contract further, triggering still higher deficits and thereby forcing policymakers to institute additional austerity measures, which in turn, would cause still greater economic contraction.

The private economic forecasting firm Macroeconomic Advisors (MA) found in 2011 that “recessions would be deeper and longer” under a constitutional balanced budget amendment. If such an amendment had been ratified in 2011 and were being enforced for fiscal year 2012, “the effect on the economy would be catastrophic,” MA concluded, and would double the unemployment rate.

Most recent proposals to write a balanced budget requirement into the U.S. Constitution would allow Congress to waive the balanced budget stricture if a supermajority of both chambers voted to do so. However, data showing that the economy is in recession do not become available until months after the economy has begun to weaken and recession has set in. It could take many months before sufficient data are available to convince a congressional supermajority to waive the balanced-budget requirement, if they ever would. In the meantime, substantial economic damage — and much larger job losses — would have resulted from the fiscal austerity measures the balanced-budget mandate would have forced.

Requiring that federal spending in any year be offset by revenues collected in that same year would also cause other problems. Social Security would effectively be prevented from drawing down its reserves from previous years to pay benefits in a later year and, instead, could be forced to cut benefits even if it had ample balances in its trust funds, as it does today. The same would be true for Medicare Part A and for military retirement and civil service retirement programs. Nor could the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation respond quickly to bank or pension fund failures by using its assets to pay deposit or pension insurance, unless it could do so without causing the budget to slip out of balance.

Proponents of a constitutional balanced budget amendment often argue that states and families must balance their budgets each year and the federal government should do the same. Yet this is a false analogy. While states must balance their operating budgets, they can — and regularly do — borrow for capital projects such as roads, schools, and water treatment plants. And families borrow, as well, such as when they take out mortgages to buy homes or loans to send children to college. In contrast, the proposed constitutional amendment would bar the federal government from borrowing to make worthy investments even if they have substantial future pay-offs. And, as with Social Security, the amendment would prohibit using past savings for current purchases; if a family had to live under its strictures, not only would mortgages be prohibited, but so too would buying a house from years of prior savings.

a For more on the risks of a constitutional balanced budget amendment, see Richard Kogan, “Constitutional Balanced Budget Amendment Poses Serious Risks,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated January 18, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4166.

Most of the recent resolutions closely follow ALEC’s model legislation, the key sentence of which reads:

The legislature of the State of ______ hereby applies to Congress, under the provisions of Article V of the Constitution of the United States, for the calling of a convention of the states limited to proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States requiring that in the absence of a national emergency the total of all Federal outlays for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated Federal revenues for that fiscal year.

Most of the resolutions enacted in the last three years add a final clause: “together with any related and appropriate fiscal constraints.” That language opens the door to any constitutional amendments that a convention might decide fit under this broad rubric, including placing a rigid ceiling on federal spending so that all (or virtually all) deficit reduction has to come from cutting federal programs such as Social Security or Medicare, with little or none coming from revenue-raising measures. Such a ceiling would reduce or eliminate any pressure to produce deficit reduction packages that pair spending reductions with increased revenue from closing unproductive special-interest tax loopholes or from combatting tax avoidance by powerful corporations. ALEC’s most recent version of the model legislation specifically includes this additional clause.[6]

As ALEC recommends, each recent state-passed resolution also says that it should be aggregated with the balanced budget amendment resolutions that other states have approved (and not subsequently rescinded), even though those other resolutions are not identical and most are over 30 years old. Whether Congress would agree to count all such other state resolutions is unknown. The question is important, because the Constitution grants solely to Congress the power to determine whether the 34-state threshold has been met. The Constitution makes no provision for a presidential veto of a congressional resolution calling a constitutional convention; and such a resolution consequently appears not to require a Presidential signature. In other words, if enough additional states adopt resolutions calling for a constitutional convention and Congress rules that the 34-state threshold has been met, a convention must be held.

Besides the “balanced budget amendment” resolutions, some states have enacted or are considering related resolutions seeking a constitutional convention to impose broader restrictions on federal power. Eight states — Alabama, Alaska, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Tennessee — have all enacted resolutions in recent years that call for a convention to propose amendments to “impose fiscal restraints on the federal government, limit the power and jurisdiction of the federal government, and limit the terms of office for its officials and for members of Congress.”[7]

States’ Ability to Control a Convention Is Highly Questionable

ALEC and its allies assert that states can control the operations and agenda of a convention and sharply limit the actions of their delegates. But there is no consensus on this question among constitutional scholars or others who have studied the question carefully; the selective quotations that convention proponents cite from the 1780s do not reflect a consensus among the Framers of the Constitution and do not have the force of law. Even more importantly, no court or other body exists with the authority to enforce any such rules and to override the decisions of a constitutional convention.

A number of prominent constitutional experts have warned of the dangers of calling a new constitutional convention (see Box 2). These concerns are justified, for several reasons:

Once Called, Convention Could Write Its Own Rules

Because a constitutional convention has not been held since 1787, the nation has established no orderly procedures for the formation and operation of one. While the Congress that calls a constitutional convention in response to states’ petitions likely would propose certain ground rules, debate among constitutional scholars is contentious on what those rules might be. As a result, many fundamental questions remain unanswered.

For example, would votes in the convention be allocated among states according to population or would every state have one vote? The original Continental Congress operated on a one-state, one-vote basis, and every state has equal weight under Article V’s ratification procedures. If every state likewise has one vote in a new convention, small states with a minority of the country’s population could control the amendment-writing process. The 26 least populous states contain less than 18 percent of the nation’s people.

Box 2: Constitutional Experts Warn That States Cannot Control a Convention

A number of prominent legal experts have warned that states cannot control a constitutional convention or that calling one could open up the Constitution to significant and unpredictable changes. For instance:

“I certainly would not want a constitutional convention. Whoa! Who knows what would come out of it?”a

Former Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia

“[T]here is no way to effectively limit or muzzle the actions of a Constitutional Convention. The Convention could make its own rules and set its own agenda. Congress might try to limit the Convention to one amendment or one issue, but there is no way to assure that the Convention would obey. After a Convention is convened, it will be too late to stop the Convention if we don’t like its agenda.”b

Former Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger

“There is no enforceable mechanism to prevent a convention from reporting out wholesale changes to our Constitution and Bill of Rights.”c

Former Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg

“First of all, we have developed orderly procedures over the past couple of centuries for resolving [some of the many] ambiguities [in the Constitution], but no comparable procedures for resolving [questions surrounding a convention]. Second, difficult interpretive questions about the Bill of Rights or the scope of the taxing power or the commerce power tend to arise one at a time, while questions surrounding the convention process would more or less need to be resolved all at once. And third, the stakes in this case in this instance are vastly greater, because what you’re doing is putting the whole Constitution up for grabs.”d

Professor Laurence Tribe, Harvard Law School

“[S]tate legislators do not have the right to dictate the terms of constitutional debate. On the contrary, they may be eliminated entirely if Congress decides that state conventions would be more appropriate vehicles for ratification. The states have the last say on amendments, but the Constitution permits them to consider only those proposals that emerge from a national institution free to consider all possible responses to an alleged constitutional deficiency. . . Nobody thinks we are now in the midst of constitutional crisis. Why, then, should we put the work of the first convention in jeopardy?”e

Professor Bruce Ackerman, Yale Law School

a Marcia Coyle, “Scalia, Ginsberg Offer Amendments to the Constitution,” Legal Times, April 17, 2014, http://www.nationallawjournal.com/legaltimes/id=1202651605161/Scalia,-Ginsburg-Offer-Amendments-to-the-Constitution?slreturn=20140421101513. In the 1970s, as a professor, Scalia argued that a convention was worth the risks he saw at the time. By 2014, as a Justice, Scalia seemed to have grown much more worried about those risks.

b Letter from Chief Justice Warren Burger to Phyllis Schlafly, June 22, 1988, http://constitution.i2i.org/files/2013/11/Burger-letter2.pdf.

c Arthur Goldberg, “Steer clear of constitutional convention,” Miami Herald, September 14, 1986.

d Remarks as part of the Conference on the Constitutional Convention, Harvard Law School, September 24-25, 2011, Legal Panel, recording available at http://www.conconcon.org/archive.php.

e Bruce Ackerman, “Unconstitutional Convention: State legislatures can’t dictate the terms of constitutional amendment,” The New Republic, March 3, 1979.

Also unclear is whether the convention would need a supermajority (of states or delegates) to propose amendments. Congress may only propose constitutional amendments by a two-thirds vote in each chamber, but Article V is silent on whether a simple majority vote in a constitutional convention would suffice. With the country closely divided on many issues, a simple majority requirement could allow amendments to move forward despite opposition from many or even most voters, especially if all states had equal votes in the convention.

Another critical question is how states would choose their delegations. In today’s highly partisan environment, majorities in state legislatures may be tempted to select delegations that reflect only their views rather than a broader spectrum of opinion within the state.

Finally, even assuming Congress sets ground rules for a convention, the convention itself could disregard those instructions once it convened; after all, there is no enforcement mechanism. Even if Congress purported to make its instructions binding, the courts likely would refuse to enforce Congress’s instructions, both because Article V does not clearly grant Congress the power to make binding instructions and because the courts generally regard such matters as “political questions” that the judicial branch does not wade into.

Convention Could Set Its Own Agenda, Possibly Influenced by Powerful Interest Groups

The only national constitutional convention ever held — the 1787 assembly in Philadelphia that produced the current Constitution — disregarded its original charge, which was to amend the Articles of Confederation to promote trade among the states. Instead it wrote an entirely new governing document, effectively abolishing the Articles of Confederation and superseding them with a new design of government. A convention held today could set its own agenda, too.

Further, the opportunity to bypass Congress and write major policy changes into the Constitution — where they would be extremely difficult to remove — would likely tempt powerful, well-funded interest groups to influence the process and press for changes beyond those initially envisioned. After all, there are no federal or state limits on spending to influence delegates to a constitutional convention. No one can predict with confidence what would happen, for example, if Wall Street concerns sought to ban the taxation of capital income or prohibit market regulations designed to prevent another financial crisis, or if energy companies sought to ban a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system.

In such a highly contentious political environment, delegates could cut deals resulting in amendments covering multiple topics. Although most constitutional amendments have addressed only a single issue, nothing in Article V requires this. The Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, and Fourteenth Amendments all combined provisions on several different subjects.[8] Provisions considered radical or damaging, at least in some states, could be attached to highly popular proposals in a single amendment, making their passage more likely.

Further, the broad language of several state resolutions enacted recently may increase the likelihood that a convention would enact sweeping and unforeseen changes. As noted above, most recent resolutions explicitly call for amendments imposing “any related and appropriate fiscal constraints” on the federal government — terms so broad that they could encompass an enormous range of changes in the government’s basic operations.

The resolutions that passed in recent years in Alabama, Alaska, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Tennessee called for amendments to “impose fiscal restraints on the federal government, limit the power and jurisdiction of the federal government, and limit the terms of office for its officials and for members of Congress,” which envisions an even broader range of amendments. Even if Congress called a convention for the purpose of proposing a balanced budget amendment only, the convention once called could use the passage of these broader resolutions as justification to pursue a broader agenda, especially if more states have passed the more expansive resolution by the time a convention is called.

In sum, there is no way to predict what constitutional amendments the delegates to a convention might adopt.

Convention Could Change Ratification Process

The 1787 convention also completely rewrote the Articles of Confederation’s amendment procedures in a way that made it much easier to secure adoption of the convention’s changes. Under the Articles of Confederation, proposed amendments had to be approved by Congress and then ratified by all 13 states to take effect. Rhode Island, which opposed the kinds of changes that the 1787 convention was called to propose, declined to send delegates to the convention, apparently confident that the requirement for unanimous state approval meant it could block any resulting proposals that harmed its interests.

Instead, the other states’ delegates bypassed Rhode Island and created a new ratification process that made the new Constitution effective with the consent of only nine states and cut Congress out of the amendment process entirely. Rhode Island opposed the new Constitution and resisted ratifying for several years. Eventually, however, left only with the choice of seceding or going along, it was forced to succumb. The current three-quarters requirement was imposed only for later constitutional amendments.

This suggests that a new convention could propose to alter Article V of the Constitution, which requires three-quarters of the states to ratify proposed constitutional amendments emerging from a convention. A new convention could, for example, provide that its amendments be considered ratified if approved by two-thirds of the states, or even by a national referendum, citing the precedent of the 1787 convention. If the ratifying states went along, dissenters would have no recourse to enforce Article V’s three-quarters requirement and ultimately would face the same type of choice that Rhode Island did.

No Other Body — Including the Courts — Has Clear Authority Over a Convention

The Constitution provides for no authority above that of a constitutional convention. This makes it unlikely that the courts or any other institution could intervene if a convention failed to limit itself to the language of state resolutions calling for a convention or to the congressional resolution establishing the convention.

Moreover, even if the courts determined that they had the authority to rule, they would be unlikely to intervene if a convention veered away from its original charge. Article V contains only two limited restrictions on the scope of constitutional amendments (one of which expired two centuries ago). Absent guidance from the Constitution’s text, the Supreme Court likely would regard this as a “political question” inappropriate for judicial resolution (consistent with how the Court has treated other highly charged matters on which the Constitution provides no judicially enforceable standard). A court would have great difficulty explaining why a convention should be bound by state resolutions, given that the 1787 convention disregarded both its own stated purpose and the Articles of Confederation’s amendment procedures.

In addition, although some states’ resolutions seek to bar their convention delegates from voting for amendments outside the subject matter of the resolution the state has adopted, the courts likely would not intervene in a dispute between a state and a delegate, viewing it, too, as a “political question.” And if the courts did intervene, they likely would be unsympathetic to states’ efforts to constrain delegates, given that delegates to the 1787 convention ignored their state legislatures’ instructions.

Even if states could recall delegates, it likely would have no practical effect. Unlike a state legislature, a constitutional convention is a one-time body; once it has voted to propose a set of amendments to the Constitution, its work is over and it disbands. Recalling delegates at that point would be irrelevant.

Conclusion

States should be deeply skeptical of claims by ALEC and others that states will control the operations and outcome of a convention called under the Constitution’s Article V. Fundamental questions about how a convention would work remain unresolved. A convention likely would be extremely contentious and politicized, with results impossible to predict.

Further, nothing could prevent a convention from emulating the only previous convention — the one in 1787 — by going beyond its original mandate, proposing unforeseen changes to the Constitution, and even altering the ratification rules. Some states might challenge the actions of their delegates, but with the courts unlikely to intervene, these efforts would likely fail.

States would be prudent to avoid these risks and reject resolutions calling for a constitutional convention. States that have already approved such resolutions would be wise to rescind them.

End Notes

[1] Michael Leachman is Director of State Fiscal Research at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. David Super is Professor of Law at Georgetown University Law Center.

[2] Marcia Coyle, “Scalia, Ginsberg Offer Amendments to the Constitution,” Legal Times, April 17, 2014, http://www.nationallawjournal.com/legaltimes/id=1202651605161/Scalia,-Ginsburg-Offer-Amendments-to-the-Constitution?slreturn=20140421101513.

[3] Letter from Chief Justice Warren Burger to Phyllis Schlafly, June 22, 1988, http://constitution.i2i.org/files/2013/11/Burger-letter2.pdf.

[4] ALEC’s latest handbook is available here: https://www.alec.org/app/uploads/2016/06/2016-Article-V_FINAL_WEB.pdf.

[5] For proponents’ latest description of their goals, see http://bba4usa.org/.

[6] See p. 26 of ALEC’s handbook, here: https://www.alec.org/app/uploads/2016/06/2016-Article-V_FINAL_WEB.pdf.

[7] A group called Citizens for Self-Governance is promoting this resolution. See the group’s “Convention of States Project” website at http://conventionofstates.com.

[8] The Fourteenth Amendment gives U.S. citizenship to those born or naturalized in the United States, protects the privileges and immunities of U.S. citizens, requires states to afford people due process of law, and requires equal protection of law — and all of that is only in its first (of five) sections. Its remaining provisions address numerous controversies active in the post-Civil War era when it was proposed, including changes in electoral rules, eligibility of former confederates for federal office, and the treatment of war-related debts. The Fifth Amendment requires indictments prior to most major federal prosecutions, prohibits double jeopardy, establishes the right against self-incrimination, creates a general right to due process, and prohibits uncompensated government seizures of private property. The Sixth Amendment requires speedy and public trials, specifies the location for criminal trials, gives defendants the right to an impartial jury, establishes a right to counsel in criminal cases, provides for cross-examination of prosecution witnesses, allows defendants to subpoena their own witnesses, and mandates a clear statement of the charges. The Eighth Amendment prohibits cruel and unusual punishment, limits the amount of bail accused defendants may be required to post, and bars “excessive” fines. At various times, some of these rights have proven intensely controversial while others in the same amendment were widely accepted.

More from the Authors