Some policymakers and analysts have proposed to convert Medicare to a "premium support" system — that is, replace its guarantee of health coverage with a flat payment that beneficiaries could use to help them purchase private insurance or, in some versions, traditional Medicare. But proponents have crafted a widely diverse set of proposals that they call premium support, and some leading proposals of recent years — such as the plan from House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan that the House approved in April — differ greatly, in design and rationale, from the premium support concept that Henry Aaron and Robert Reischauer introduced in 1995.

Aaron and Reischauer, for instance, did not seek to use premium support to achieve big savings in federal health care spending. They were focused, instead, on encouraging people to choose insurance plans that matched their preferences and making people more responsible for the financial consequences of their choices. Chairman Ryan and other leading proponents of premium support, however, clearly view it as a tool to achieve major savings in federal health care spending over time. That's only one of the major differences between the original concept and recent leading proposals. In fact, recent proposals are so different from the original Aaron-Reischauer concept that Aaron no longer supports the very idea. (See box, page 6.)

Premium support — no matter what form it takes — raises several very important and challenging issues that may seem manageable in theory but would be extremely hard to resolve satisfactorily in practice. And failure to resolve these challenges satisfactorily would likely lead to a two-tier health care system: the affluent would receive the most up-to-date medical care (since they could buy comprehensive coverage by supplementing the premium support payment with their own funds), while those of modest means who could only afford the coverage that their premium support payment buys would increasingly find medical advances out of their reach.

The main issues that premiums support raises are:

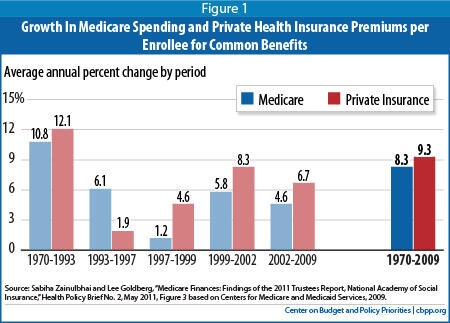

- Maintaining traditional Medicare's ability to contain costs. Traditional fee-for-service Medicare delivers health care services more economically than private insurance because it has low administrative costs and it can use its bargaining power to hold down payment rates to providers. It also has a better record of limiting the growth of costs. From 1970 to 2009, Medicare spending per enrollee grew by an average of 1 percentage point less each year than comparable private health insurance premiums. Medicare has spearheaded several reforms in the health care system to improve efficiency, and the new health reform law builds on that foundation.

Premium support proposals that phase out traditional Medicare, such as Chairman Ryan's plan, would likely increase total health care spending (public and private combined), as the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO's) analysis of the Ryan plan indicates, because they would lose these cost-containing features of Medicare. CBO estimates the House plan would increase total health spending attributable to the average 65-year-old beneficiary by almost 40 percent and increase that beneficiary's out-of-pocket spending by over $6,000 in 2022. Even premium support proposals that retain traditional Medicare as an option for enrollees would risk undercutting Medicare's ability to serve as a leader in controlling costs by depriving it of the considerable market power (in dealing with health care providers) that it derives from its large enrollment. - Providing adequate premium support payments. As Aaron and Reischauer originally conceived it, the premium support payments that beneficiaries would receive to help them buy health coverage would reflect current levels of Medicare expenditures per beneficiary, and would keep pace with the growth in health care costs over time . But, in most recent premium support proposals — including the Ryan plan and a plan from a panel co-chaired by former Clinton budget director Alice Rivlin and former Senate Budget Committee chairman Pete Domenici — the premium support payments would grow each year in accordance with an index unrelated to health care, such as growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita or the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Since GDP per capita and the CPI have consistently grown significantly slower than health costs and are expected to continue doing so, these proposals would shift more and more health care costs to beneficiaries each year through higher premiums and out-of-pocket charges.

- Preventing insurers from focusing on attracting healthier enrollees. Roughly one-quarter of Medicare beneficiaries now receive coverage through private Medicare Advantage plans rather than traditional Medicare. Medicare adjusts its payments to these private plans to reflect their enrollees' health status: plans with relatively healthy enrollees receive lower payments because healthier people cost less to cover. But this process, known as risk adjustment, is imperfect and still leaves insurers with a financial incentive to attract healthier people and discourage sicker ones from signing up; and the resulting overpayments to some plans inflate Medicare's overall costs.

Insufficient risk adjustment could create much greater problems under a premium support system; it could significantly separate healthier and less-healthy enrollees into different health plans, driving up the costs of plans serving the less-healthy group and, in turn, making those plans less financially viable. In particular, under a premium support system that gives beneficiaries an option to select traditional Medicare, traditional Medicare likely would disproportionately attract less-healthy enrollees — and inadequate risk adjustment could drive up its costs and threaten traditional Medicare's long-term viability. - Protecting low-income beneficiaries. Currently, very low-income Medicare beneficiaries are also eligible for Medicaid, while beneficiaries with slightly higher (but still low) incomes receive assistance through Medicaid to help meet Medicare's substantial premiums and cost-sharing charges. Under a Medicare premium support system, low-income beneficiaries would need substantial financial assistance to enable them to afford insurance and have access to care. Some premium support proposals, including the Ryan plan, do not address this matter adequately and would force large numbers of vulnerable low-income Medicare beneficiaries to pay much higher out-of-pocket costs or forgo needed care.

For almost 40 years, Medicare beneficiaries have been able to receive their benefits through private health plans, although the arrangements have evolved significantly over that time. In 2010, some 25 percent of beneficiaries were enrolled in a private health plan through the Medicare Advantage (MA) program.[1] Medicare paid MA plans 9 percent more in 2010 than what it would have cost traditional Medicare to cover comparable enrollees,[2] the result of a large increase in MA payments contained in the 2003 Medicare prescription drug law. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 will gradually reduce MA payment rates to bring them more in line with payments in traditional Medicare, although some overpayments will continue.

The remaining three-quarters of Medicare beneficiaries are in traditional Medicare, which allows them to receive care from virtually any licensed health care provider and to receive any covered service that they and their provider consider appropriate. Most elderly people are covered by the Hospital Insurance portion of Medicare (Part A) because they or their spouse have paid Medicare payroll taxes into the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund for at least ten years. Enrollment in Supplementary Medical Insurance (Part B, which pays for physician and other services) and outpatient prescription drug coverage (Part D) each requires payment of a monthly premium that covers about 25 percent of the cost of the insurance. General revenues cover the other three-quarters of the cost.

The Part B premium is a uniform national amount that does not vary with a beneficiary's age or place of residence. Low-income beneficiaries are eligible for extra assistance to help pay their premiums and cost-sharing, and high-income people pay additional income-tested premiums. Under Part D, Medicare delivers prescription drug coverage exclusively through private insurance plans that contract with the program: either stand-alone drug plans or Medicare Advantage plans that package drug coverage with the rest of Medicare coverage. Almost 90 percent of Medicare beneficiaries also have some type of supplemental insurance that fills in part of Medicare's cost-sharing requirements and protects beneficiaries against catastrophic health care costs, which Medicare (unlike most employer-sponsored health plans) does not fully cover.[3]

The law requires Medicare Advantage plans to offer the same basic benefits as traditional Medicare and to provide overall coverage (including cost sharing charges) that is actuarially equivalent to Medicare.[4] Beneficiaries may enroll in an MA plan when they first become eligible for Medicare or during an annual open enrollment period. Medicare provides beneficiaries with information about the MA plans available in their area, and plans may also market directly to beneficiaries.

Beneficiaries enrolled in an MA plan must pay the Part B premium (less any rebate that the private plan provides), and often pay an additional premium specific to the MA plan for prescription drug coverage and supplemental benefits. Medicare payments to MA plans are tied to local per capita expenditures in traditional fee-for-service Medicare and to the plans' "bids" (their estimated cost of providing Part A and B benefits to an average enrollee). Medicare also adjusts its payments to MA plans to reflect the health status of each plan's enrollees. [5]

Because MA plans have been overpaid, they have been able to offer benefits beyond those that traditional Medicare provides. The most common enhancements are reductions in cost sharing and additional services such as dental and eye care and wellness benefits. [6] Starting in 2011, all MA plans must limit out-of-pocket costs (excluding premiums) to $6,700 (traditional Medicare has no limit on out-of-pocket costs).[7]

Henry Aaron and Robert Reischauer introduced the phrase "premium support" in an article in Health Affairs in 1995. [8] As Aaron explains, "This term has since been applied to several proposals built around the principle that health care services should be financed by the government but managed by private insurance plans competing on premiums and services." [9] The original Aaron-Reischauer proposal for Medicare premium support had the following major elements:

- Medicare would pay health insurance plans a specified amount toward a beneficiary's purchase of a policy that covered a standard set of services, combining current Medicare benefits with protection against catastrophic costs. Medicare would no longer directly reimburse health care providers for the provision of covered services.

- Initially, the federal premium support payment would be based on the average cost of the standard benefit package in each health insurance market area. After a transitional period, the payment would grow at the same rate as per capita spending on health care for the nonelderly.

- The premium support payment in any market area would be the same regardless of which health insurance plan a beneficiary chose. Beneficiaries who chose a plan that cost more than the premium support payment would have to pay the difference.

- Low-income Medicare beneficiaries would receive additional support to replace the premium and cost-sharing assistance that Medicaid now provides.

- To discourage health insurance plans from trying to enroll less costly beneficiaries, Medicare would adjust its payments to plans on behalf of each beneficiary to reflect the beneficiary's health status. (This is termed "risk adjustment.")

Premium support follows in many ways the concept of "managed competition" that Alain Enthoven, a Stanford economist, and others developed in the l970s and 1980s.[10] Managed competition aims to structure the market for health insurance in a way that will encourage insurance plans to compete on the basis of price and health-care quality (or value for money), rather than on the basis of which insurance plans can best attract healthy (and therefore less costly) enrollees and deter sicker ones. In explaining the rationale for premium support, Aaron and Reischauer wrote:

We advocate this approach not because we necessarily believe that managed care and managed competition will produce huge savings. Such savings are highly uncertain and depend on unpredictable developments. Rather, a framework that forces people to face the consequences of their choices in the delivery of medical care should encourage them to choose the plans whose style of care matches their preferences, and we believe that enrollees should bear the financial consequences of their choices.[11]

In subsequent writings, Aaron has emphasized that premium support (as he and Reischauer originally conceived it) would link the annual increases in the amount of the premium support payments that beneficiaries receive "to increases in general health costs, rather than to an index that is independent of health care costs. This last feature distinguishes managed competition from voucher plans, which link the annual increase in the federal contribution toward a beneficiary's costs in purchasing insurance to non-health indicators such as income or economic growth." [12]

Because premium support proposals are likely to shift costs to beneficiaries rather than slow the underlying growth of health care spending, Aaron no longer backs premium support. (See the box on page 6.)

In the years since Aaron and Reischauer sketched out their approach to premium support, others have advanced variants on this idea but with some important differences. This section summarizes some of the premium support plans proposed since 1995.

Premium support gained prominence in early 1999 with a proposal by Sen. John Breaux (D-LA) and Rep. Bill Thomas (R-CA), co-chairs of the National Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare.[13] Although their proposal did not gather the requisite supermajority to receive the commission's endorsement, it has received considerable attention over the years.

Henry Aaron, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, helped developed the concept of premium support. In a recent commentary, he explains why he no longer backs the idea.

Robert Reischauer and I coined the term "premium support" for a plan intended to address at least some of [the] objections [to a voucher system]. Premium support would be tied to average health care costs, not an economic index. The menu of private insurance plans would be limited to facilitate informed choice by enrollees. A nonprofit or government agency would provide explanatory literature and extensive counseling and handle sales to avoid misleading and costly sales methods. Group-based, retrospective risk adjustments — financial transfers among plans based on the risk profiles of actual enrollees — would make competition based on risk selection unprofitable. . . .

Although the Rivlin-Ryan and House Budget Committee plans are called "premium support," they actually jettison all or most of the consumer protections that distinguish premium support from bare vouchers. Both would shift costs to Medicare enrollees. The CBO estimates that by 2030 the House Budget Committee plan would increase the out-of-pocket share of health care spending for a typical Medicare beneficiary from the current 25-to-30% range to 68%. By 2050, the House plan would cut federal health care spending by approximately two thirds. Both plans would place substantial administrative burdens on the most vulnerable and infirm of Medicare's enrollees. And both would surrender the considerable leverage that Medicare can bring to bear on providers to reduce spending and improve quality . . . .

In brief, current proposals are not premium support as Reischauer and I used the term. In addition, I now believe that even with the protections we set forth, vouchers have serious shortcomings. Only systemic health care reform holds out real promise of slowing the growth of Medicare spending. Predicted savings from vouchers or premium support are speculative. Cost shifting to the elderly, disabled, and poor and to states is not. Medicare's size confers power, so far largely untapped, that no private plan can match to promote the systemic change that can improve quality and reduce cost. The advantages of choice in health care relate less to choice of insurance plan than to choice of provider, which traditional Medicare now provides and which many private plans restrict as a management tool. Finally, the success of premium support depends on sustained and rigorous regulation of plan offerings and marketing that the current Congress shows no disposition to establish and maintain.

Source: Henry J. Aaron, "How Not to Reform Medicare," New England Journal of Medicine, 364: 1588-1589 (April 28, 2011), http://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1103764.

A key difference between the Breaux-Thomas proposal and the original Aaron-Reischauer concept is that Breaux-Thomas would have retained traditional fee-for-service Medicare as an option for beneficiaries. Breaux and Thomas also proposed a major change in the governance of Medicare. Under their proposal, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS, then called the Health Care Financing Administration) would continue to administer Medicare's fee-for-service program, but a new, independent "Medicare Board" would set the rules governing the terms of competition between traditional Medicare and the competing private plans. This recommendation apparently stemmed from both a desire to remove Congress from many of the details of administering Medicare and a belief that an inherent conflict exists in having a single agency administer a government-run fee-for-service plan and oversee a system of competing private insurance plans, as CMS currently does with respect to Medicare and Medicare Advantage.

The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 added to Medicare a prescription drug benefit that follows the premium support model. Drug benefits are provided only through private plans; there is no public option for beneficiaries to choose. Both proponents and opponents of premium support use the Medicare drug benefit to buttress their case, although the example is inexact: providing prescription drug coverage is much less expensive and much more standardized than delivering the entire Medicare benefit package.

When Congress was debating the 2003 law, some critics contended that the drug benefit would not work because few insurers would be interested in offering a stand-alone prescription drug plan, which was at the time an untested concept. Others expressed the opposite concern: that beneficiaries would be overwhelmed with choices. As it turned out, the provision of a generous government subsidy to beneficiaries to purchase the drug coverage ensured high participation and attracted a large number of insurers, and — after some initial confusion — beneficiaries and their families have learned to navigate the system. The fact that 35 million of the 49 million Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in Part D demonstrates that the premium support approach is administratively feasible, at least on this scale.[14]

Some advocates of premium support, noting that Part D costs have been lower than the Congressional Budget Office predicted when Congress enacted the drug benefit, incorrectly attribute this lower spending to efficiencies produced by competition among the private insurers that deliver the benefit. In reality, as Medicare's chief actuary, Richard Foster, has confirmed, the two main factors holding down Part D spending have been a sharp slowdown in prescription drug spending throughout the entire U.S. health care system — a development independent of the creation of Part D — and lower-than-expected enrollment in Part D.[15] Moreover, the federal government is incurring considerably higher drug costs for "dual-eligible" beneficiaries (low-income beneficiaries enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid) than it previously paid under Medicaid; this development, which the designers of Part D did not expect, does not support claims that competition among insurers has produced savings that a government-run program cannot achieve.[16]

In November 2010, a commission of the Bipartisan Policy Center co-chaired by former Clinton Office of Management and Budget Director Alice Rivlin and former Republican Senate Budget Committee Chair Pete Domenici released a deficit-reduction plan that would transition Medicare to premium support. [17] Starting in 2018, the Rivlin-Domenici plan would effectively provide a voucher to Medicare beneficiaries, which they would use to help pay the costs of enrolling in either traditional fee-for-service Medicare or a competing private insurance plan. A federal Medicare exchange would manage competition among plans and help beneficiaries choose a plan and enroll.

The voucher amount would be based on the amount of Medicare spending per enrollee in 2017, adjusted each year by the rate of growth of GDP per capita plus 1 percentage point, which is lower than the average rate at which both Medicare and private-sector health care costs per beneficiary have risen. If the voucher did not keep pace with rising costs in Medicare and throughout the U.S. health care system (as would likely be the case), a beneficiary who wished to remain in traditional Medicare would have to pay a steadily higher premium to cover the difference between the cost of that coverage and the voucher amount. Alternatively, a beneficiary could enroll in a competing private health plan that charged a lower premium because it was more efficient, used a more limited network of providers, or for other reasons[18] The Rivlin-Domenici proposal leaves many important details unspecified, including whether the private plans could require higher cost-sharing or offer less comprehensive benefits than others; if so, the private plans could offer coverage for a lower premium because the coverage they provided would be narrower.

Premium support is a major element of the fiscal year 2012 budget resolution, developed by House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-WI), which the House passed on a largely party-line vote on April 15, 2011.[19] Under the Ryan plan, people who turn 65 in 2022 and later would no longer be eligible for traditional Medicare but would instead receive a voucher to help them purchase private health insurance.[20] Plans would have to comply with minimum requirements for benefits established by the Office of Personnel Management, but benefits would not be standardized across plans.

The initial voucher amount for people turning 65 in 2022 would equal net Medicare spending per person under current law in that year, or about $8,000; the initial voucher amount would be increased each year by the rate of growth of the Consumer Price Index. Once a beneficiary started to receive Medicare, the voucher would increase with the CPI and age, since health insurance plans would be allowed to charge older enrollees more than younger ones. Medicare payments to plans on behalf of an individual would be risk-adjusted and thus would vary with the individual's health status.

Low-income individuals eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid would no longer receive any help with their Medicare premiums and cost-sharing through Medicaid. Instead, they would receive a lump-sum amount (initially $7,800) in a medical savings account to help cover their out-of-pocket costs. Like the voucher, this payment would be increased each year at the rate of growth of the CPI.

As the foregoing examples illustrate, shifting Medicare to a premium support system would raise a host of complex and interrelated issues, such as determining the role of traditional Medicare, setting and adjusting the amount of the premium support payment, discouraging private plans from attracting healthy enrollees while deterring sick ones, and protecting low-income beneficiaries.

Maintaining Traditional Medicare's Ability to Contain Costs

One of the biggest issues is whether traditional Medicare would continue to exist if the program were converted to a premium support system. The House Republican plan would close traditional Medicare to new participants and gradually phase it out, whereas some other premium support plans — such as the Rivlin-Domenici proposal — would retain it. This decision would have major implications for the structure of the health care delivery system and the system's overall costs.

Traditional Medicare has some particular strengths compared to private health plans, notably its "proven record as a policy innovator and leader." [21] As the largest U.S. purchaser and regulator of health care, Medicare exerts a major influence on the rest of the health care system. Private insurers and other public programs have widely adopted Medicare's reimbursement and coverage policies. For example, many private insurers follow Medicare's lead in approving coverage of new medical technologies. Over the years, the private sector has also typically followed Medicare's lead in adopting new payment mechanisms to increase efficiency and constrain costs — including the prospective payment system for hospitals and fee schedule for physicians.[22] Under these arrangements, Medicare pays providers based on predetermined rates, rather than paying whatever amounts the providers charge. Medicare also influences the provision of care through its conditions of participation for hospitals and health plans, reporting requirements, claims review practices, and other administrative procedures.[23] Today, for example, the prospect of receiving incentive payments from Medicare is driving health care providers to adopt health information technology, which should improve health care quality and efficiency.

Partly because of its strong record of innovation, Medicare has outperformed private insurance in holding down the growth of health costs. Over the 40 years from 1970 to 2009, Medicare spending per enrollee grew by an average of 1 percentage point

less each year than private health insurance premiums, or one-third less over the 40 years as a whole. Medicare had a better cost-control record than private insurance in five out of six subperiods during that time. (See Figure 1.)

Traditional Medicare — not private health insurance companies — has also been the leader in reforming the health care system to improve efficiency. Under the recent health reform legislation, as former OMB Director Peter Orszag explains:

Medicare [will continue] to lead the way toward the provider-value model of health care. Some private insurance firms would like to move in this direction to save money, but the private market remains too fragmented for any individual firm to engineer a wholesale change in provider incentives. Given Medicare's prominent role in the health system, it is necessary to put the program at the center of the effort to control costs. The [Affordable Care] act does so through both specific measures (such as imposing penalties through Medicare on hospitals with high rates of infection) and institutional changes (such as the creation of new bodies with the power to reduce cost growth over time without the need for new legislation). [24]

Other Affordable Care Act reforms that rely on Medicare to "lead the way" include accountable care organizations (physician-led organizations that take responsibility for the cost and quality of the care they deliver), reductions in payments to hospitals with high readmission rates, and bundled payments to providers for an episode of care.

By eliminating traditional Medicare, the House Republican plan would throw away the opportunity to use the program to promote cost reduction throughout the health care system. Even if traditional Medicare were retained under a premium support system, its ability to serve as a leader in controlling costs would shrink significantly if its enrollment dwindled. As two leading Medicare analysts explain:

Recent efforts to use Medicare's leverage as a very large purchaser to encourage health care delivery system changes that would reduce costs for all payers, not just Medicare, could be undermined if Medicare expenditures were diffused among a large number of private plans. For example, efforts at encouraging provider cooperation such as the creation of accountable care organizations or the introduction of bundled payments across providers for an episode of care would have to be adopted and perhaps coordinated among multiple competing private plans to have the same impact. [25]

Indeed, the Congressional Budget Office has concluded that replacing traditional Medicare with private health plans would drive up total health care spending attributable to Medicare beneficiaries (the beneficiaries' share plus the government's share), for two reasons. [26] First, private plans' administrative costs are much higher, amounting to 11 percent of spending for Medicare Advantage plans compared to roughly 2 percent of spending for traditional Medicare.[27] Second, private plans cannot negotiate payment rates for health care providers that are as low as Medicare's.

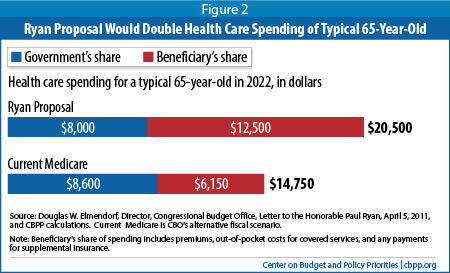

CBO estimates that in 2022 (the first year that the House Republican plan's new Medicare system would be in effect), the plan would cause total health spending attributable to the average 65-year-old Medicare beneficiary to increase from $14,750 to $20,500 — or almost 40 percent. CBO also estimates that the average 65-year-old beneficiary's out-of-pocket costs would more than double —from $6,150 a year under a continuation of traditional Medicare to $12,500 under the House plan.

[28] (See Figure 2.)

If traditional Medicare participated in a premium support system, it would be necessary to specify the terms under which it competed with private health plans. Under current rules, traditional Medicare (unlike Medicare Advantage plans) cannot offer a comprehensive benefit that includes hospital and doctor services, prescription drug coverage, and protection against catastrophic costs in a single package. Traditional Medicare is also limited in its ability to modify its benefit design, care management processes, or provider contracts without congressional approval. On the other hand, traditional Medicare benefits from its considerable market power and lower payment rates to providers. [29] Establishing the terms of competition between traditional Medicare and private plans requires addressing the questions of what agency should administer the competition, whether a "level playing field" is desirable, and, if so, how to measure and achieve it.[30]

If traditional Medicare were phased out, a number of transitional issues would arise. With no new beneficiaries added to the program, the population in traditional Medicare would gradually get older, sicker, fewer in number, and much more expensive per person to cover. Private plans could accelerate this process by enticing healthier beneficiaries to leave traditional Medicare. The House Republican proposal would protect beneficiaries from the rise in premiums that would otherwise stem from this change, but it does not specify whether they would also be protected from increases in cost-sharing requirements.[31] Moreover, as the size of the Medicare population shrank, administrative costs would rise relative to benefit payments, traditional Medicare's market power to negotiate lower payment rates to providers would erode, and providers would have less incentive to participate in the program. It could become difficult to keep traditional Medicare in operation without increases in both provider payment rates and beneficiary premiums. As a result, claims that the House plan would not affect older people now in Medicare are likely to prove incorrect.

Regardless of whether traditional Medicare continued as an option, adoption of premium support also would require rethinking whether and how Medicare can continue to perform its wider social roles, such as support for graduate medical education, rural hospitals, and hospitals that serve disproportionate numbers of low-income people. Medicare now achieves these goals largely by making higher fee-for-service payments to certain hospitals. But under premium support, traditional Medicare (if it continued) could not shoulder these burdens alone without placing it at a considerable competitive disadvantage relative to private insurance plans. If these functions were to continue, new sources of funding would have to be found.

Another crucial issue is how to set the amount of the premium support payment — both at first and in later years. This decision will determine the extent to which adoption of a premium support system shifts health care costs from Medicare to its beneficiaries.

Many premium support proposals would tie the government's initial payment to the bids (that is, the estimated cost of providing Part A and B benefits to an average enrollee) made by competing health plans, including traditional Medicare. The Breaux-Thomas proposal would have tied both initial and subsequent payments to the national average bid, adjusted for regional differences in costs. Other proposals would base payments on the weighted average bid or the lowest bid in each market area, subject to plans' capacity. According to a CBO analysis, all of these variants would save money primarily by lowering federal contributions on behalf of Medicare enrollees and shifting costs to beneficiaries. The lower the premium support payment, the lower the government's cost — and the greater the burden on beneficiaries.[32] Beneficiaries would either have to pay more or choose a cheaper plan, which might provide lower-quality care, offer less choice among providers, require higher deductibles and co-payments, or have other limitations.

The Rivlin-Domenici and House Republican proposals would tie the initial payment amount to what traditional Medicare would otherwise spend on coverage at the time that the new arrangement goes into effect. As explained above, even this approach would substantially increase health costs for beneficiaries if traditional Medicare were no longer available as an option, since private plans have higher administrative costs and payment rates.

Equally critical is the rate at which the premium support amount would increase in subsequent years. According to Henry Aaron, co-author of the original premium support proposal:

The defining attribute of the plans that Reischauer and I christened "premium support" was that the amount of support was to be indexed to average health care costs, not, as in voucher plans, to a price index or per person income. If savings were to result from the exercise of consumer choice and market discipline, that would be well and good, we argued. But savings should not come from erosion of the adequacy of support resulting from linking the payment to a slowly growing index. [33]

Under the proposals that Aaron calls vouchers, the federal government's contribution would grow at some specified rate external to the health-care sector. For example, the House Republican proposal would adjust the voucher amount annually by the rate of growth of the Consumer Price Index, which is likely to fall far short of the rate of increase of health care costs. Even many backers of the premium support concept find that growth rate to be grossly insufficient. Alice Rivlin has said, "That's a reason for me saying very strongly that I don't support the version of premium support in the Ryan plan. . . . [T]he growth rate is much, much too low."[34] Similarly, Gail Wilensky, head of the Health Care Financing Administration under President George H.W. Bush, has stated, "the rate of increase Ryan chose for the subsidy is too stringent, especially for the new program's first decade."[35]

The Rivlin-Domenici proposal would increase the voucher each year by the rate of growth of GDP per capita plus one percentage point. Although more rapid than the House Republican proposal would allow, this still would likely fail to keep pace with rising health care costs. From 1985 through 2009, for example, Medicare spending per beneficiary grew at an average rate of 7.0 percent a year, while GDP per capita growth plus one percentage point averaged 6.2 percent, and the CPI grew at 2.9 percent.[36] If this pattern persists, as is likely, both the House Republican and Rivlin-Domenici proposals would shift more and more costs onto beneficiaries over time through higher premiums and out-of-pocket charges.

Geographic variations in health care spending would prove particularly contentious in designing a premium support system for Medicare. Fee-for-service Medicare spending per elderly beneficiary varies by as much as 2½-to-1 from one locality to another. This variation is attributable to differences in several factors, including local wages and other costs, beneficiaries' health status and economic characteristics, and doctors' patterns of practice. Disentangling these factors is difficult; "the best available research does not provide a solid basis for drawing conclusions about how much of the variation in Medicare spending across localities reflects inappropriate or inefficient spending."[37]

At present, beneficiaries with traditional Medicare pay the same Part B premium no matter where they live, even though Medicare's costs differ from one region to another. Under virtually any version of premium support, however, beneficiaries in high-cost areas would end up paying higher premiums than those in low-cost areas. Any effort to reduce the variation in premiums would involve a very visible redistribution of funds from low-cost to high-cost areas.

Medicare beneficiaries also now pay the same premium irrespective of age, a feature that most premium support proposals would retain. In the House Republican proposal, however, premiums and premium support payments would vary with the age of the beneficiary. This arrangement would pose serious problems. Even if the premium support payment covered the same fraction of the cost of a health insurance plan regardless of the beneficiary's age, beneficiaries would still have to pay substantially higher premium amounts as they grew older. Average health care spending is almost twice as high for those 85 or older as for those ages 65 to 74,[38] and under the House Republican proposal, premiums would grow proportionately. And since incomes tend to decline as people age, this arrangement would impose the greatest costs on those least able to afford them. In addition, if the premium support payment grew less rapidly with age than the premiums that insurers charge, older beneficiaries would fall even further behind.

Some premium support proposals would require higher-income beneficiaries to pay more for their coverage. In the House Republican plan, beneficiaries with incomes over $85,000 ($170,000 for a couple) would receive a voucher for half of the basic amount or less. This means-testing of the voucher amount is apparently intended to replace the income-testing of Medicare premiums in current law. Some other premium support proposals would provide no government contribution whatever for people above a specified income threshold.

The uneven distribution of health care spending among the population creates further complications for premium support. In any year, most people incur relatively little in the way of health care costs, and a few people have very high costs. This skewed distribution applies in Medicare as well as in every other type of health insurance coverage. In 2006, for example, the most expensive 5 percent of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare accounted for 39 percent of total spending, while the least expensive half of beneficiaries accounted for only 4 percent of spending. [39]

High-cost and low-cost enrollees do not distribute themselves evenly among traditional Medicare and private plans. More expensive enrollees gravitate towards traditional Medicare, while Medicare Advantage plans disproportionately sign up low-cost (healthier-than-average) beneficiaries. [40] If Medicare ignored these differences and paid private plans based on the average spending for all Medicare enrollees, it would significantly overpay them. Therefore, Medicare tries to take account of differences in the health status of enrollees through a process known as risk adjustment. To the extent that an MA plan enrolls people who are in better-than-average health — as reflected by demographic information, diagnosis codes, and other factors — Medicare reduces its per-capita payments to the plan. Risk adjustment aims "to ensure that the highly skewed distribution of medical costs across any population does not destabilize insurance markets by favoring some insurers over others."[41]

Over the years, Medicare's risk-adjustment methods have gradually become more sophisticated. Nevertheless, the current model continues to over-predict costs for beneficiaries who are in good health and under-predict costs for those who are in poor health. [42] If private health insurance plans have access to information about the health of beneficiaries that is not used in the risk-adjustment process, they can use that information to exploit the limitations in the process, and they can profit from taking steps to attract relatively healthy beneficiaries and discourage enrollment by sicker ones. Indeed, Medicare Advantage plans have a history of designing benefit packages and marketing efforts to do just that,[43] and they continue to focus resources on retaining their healthiest and most profitable enrollees. Plans also engage in "upcoding" — assigning diagnosis codes that make their enrollees look sicker than they actually are and thereby undercut the ability of risk adjustment to adjust for differences in health statues among enrollees in different insurance arrangements. As a result of these flaws in the risk-adjustment process, overpayments to MA plans that enroll healthier beneficiaries continue to inflate Medicare's costs.[44]

Under Medicare's current structure, inadequate risk adjustment increases the payments that Medicare Advantage plans receive but does not reduce the payments received by traditional Medicare.[45] Some of the overpayments to MA plans end up as higher profits, and some result in lower premiums or increased benefits for the plans' participants. Since the overpayments raise Medicare's overall cost, beneficiaries in traditional Medicare face slightly higher Part B premiums than they otherwise would, and taxpayers have to pay slightly more to finance the program. Traditional Medicare, however, is not fundamentally threatened.

In a premium support system, however, insufficient risk adjustment would create far bigger problems. If traditional Medicare were not adequately paid for its relatively high-cost enrollees, its premiums would rise substantially, further discouraging enrollment by healthier beneficiaries — which in turn would raise premiums in traditional Medicare still higher. The lower the premium support payment, the more rapidly this process would unfold. Without a sufficiently accurate risk-adjustment mechanism, "plans (such as traditional Medicare) that attracted disabled or less healthy enrollees would be at a competitive disadvantage and subject to financial losses, and beneficiaries who might be expected to require more care would face higher premiums and severe access problems."[46] Over time, traditional Medicare could become increasingly unsustainable.

Because risk adjustment is imperfect, a premium support system would need to take further steps to assure that health plans competed based on the price and quality of their offerings and not on their ability to enroll healthier beneficiaries. Ideally, plans would be required to offer a standard set of benefits and cost-sharing. Standardizing the benefit package would preclude plans from tailoring their benefits to attract healthier-than-average beneficiaries — for example, by subsidizing gym memberships while providing less coverage for certain costly medical conditions — and would make it easier for the government to evaluate plans' bids. Plans' marketing efforts would also need to be monitored to prevent their use to attract healthy beneficiaries and subtly deter sicker ones. These steps would also help Medicare beneficiaries make more informed choices about the value of competing plans.

The original Aaron-Reischauer proposal included these critical features. The House Republican plan omits them, however, and the less detailed Rivlin-Domenici plan is largely silent on them.

Any premium support proposal will have to take steps to assure that low-income Medicare beneficiaries maintain access to affordable health coverage. These beneficiaries are particularly vulnerable; they are more likely to suffer from chronic illness and account for a disproportionate share of health care spending.

Currently, very low-income Medicare beneficiaries are eligible for the full range of Medicaid services, which are more extensive than those Medicare provides. Beneficiaries with slightly higher (but still low) incomes receive assistance through Medicaid with Medicare's premiums and cost sharing charges. Low-income beneficiaries are also eligible for extra help with their prescription drug costs. [47]

In a premium support system, providing additional assistance to low-income beneficiaries would not only assure their access to needed care but also help avoid risk selection by insurance plans. Without such assistance, more costly plans that offer an expanded choice of providers or better amenities would attract more affluent enrollees. Because people with higher incomes tend to be in better health, such self-selection would exacerbate the risk selection problem (that is, the separation of healthy and less-healthy people into different insurance plans). "To have some choice of plans," write Aaron and Reischauer, "low-income participants would have to be provided with some sort of premium supplement to replace the current Medicaid assistance. . . . For example, [these supplements] might be sufficient to allow a person with an income below the poverty threshold to participate at no cost in any plan that charged a premium below the median in the region.[48]

The Rivlin-Domenici proposal specifies that beneficiaries "whose Part B and Part D premiums are paid for by Medicaid programs would not be affected" by the plan, but it provides no details as to how it would achieve this result. This lack of specificity is potentially serious, since the proposal would also increase Medicare's cost-sharing charges (deductibles and co-insurance), while adding protection against catastrophic medical expenses. Whatever the details, the proposal would shift costs to states (which share in the financing of Medicaid) and to many low-income beneficiaries who are not eligible for Medicaid.

The House Republican proposal would take an even more limited — and more problematic — approach. Low-income individuals eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid would no longer receive any help with their Medicare premiums and cost-sharing through Medicaid. Instead, they would simply be given a lump-sum amount in a medical savings account to help pay for their out-of-pocket costs. The lump-sum amount (initially $7,800 in 2022) would be substantially less than would be needed to pay for their premiums and cost-sharing (which would be $12,500 for a typical 65-year-old in 2022, according to CBO). As a result, low-income beneficiaries as a group would be heavily disadvantaged, and many of those who are the sickest and incur the highest health care costs — including poor, frail people who are very old and poor people afflicted with severe disabilities — would be unable to afford needed care. Moreover, this annual payment (like the voucher) would be increased only at the rate of growth of the Consumer Price Index, which is much slower than health care costs have been rising in recent decades. It thus would become less and less adequate over time. [49]

Proponents of the House Republican proposal, such as Rep. Ryan, have described it as doing "more" for low-income Medicare beneficiaries, leading some commentators to assume mistakenly that it does more for such beneficiaries than the current Medicare program — or at a minimum, that it does not make low-income beneficiaries significantly worse off. In fact, the proposal would result in deep cuts in support for low-income beneficiaries, especially those who are the sickest. It turns out that "more" simply means that low-income beneficiaries would receive more assistance than higher-income-beneficiaries do — something that has been true for decades. The plan's proponents gloss over the fact that such assistance would represent a sharp reduction from what such beneficiaries receive today and would likely lead many of them to forgo needed care because they would be unable to afford it.

Some commentators have suggested that there is little difference between premium support and the health insurance system established by the Affordable Care Act. But while both would provide federal support to purchase private health insurance through a public exchange, the two differ in critically important ways.

The first key difference concerns the amount of public support provided to help beneficiaries purchase insurance. Under the Affordable Care Act, the premium credits that low- and moderate-income families will receive to help buy coverage through the new health insurance exchanges are designed to keep pace with health insurance costs, at least for the first five years.[50] In the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program — another frequent point of comparison — the government payment (which equals approximately three-quarters of the average premium) also keeps pace with the growth in health costs.[51]

In contrast, in recent premium support proposals, the amount of the premium support payment would, from the outset, grow less rapidly than health costs. As a result, Medicare beneficiaries would bear an increasing share of the health costs; after a number of years, those added costs would become substantial. Thus, what might first appear to be simply a difference of degree would soon amount to a difference of kind. Adjusting the premium support payment by an economic index external to health care costs, rather than by a measure of the growth in health costs, is — according to the Aaron-Reischauer definition — precisely what differentiates a premium support system from a voucher.

A second key difference is that the Affordable Care Act and Medicare premium support proposals start from very different situations. The Affordable Care Act will extend health coverage to tens of millions of previously uninsured Americans by providing access to subsidized private insurance. The House Republican proposal would eliminate traditional Medicare and require elderly and disabled people to enroll in private insurance plans.

Medicare is not only less expensive than private insurance, as explained above, but its costs have grown less rapidly. Traditional Medicare has been the leader in advancing various reforms in the health care payment system in order to promote more efficient delivery of health care, and the Affordable Care Act places Medicare at the center of future efforts to control costs. As a result, phasing out or shrinking traditional Medicare would represent a significant step backward on the path to slowing health care costs.

Although designing a premium support system that would address the issues identified here may be technically possible, it would be extremely difficult to achieve.

In theory, a premium support system could be structured to assure that traditional Medicare and private plans compete on a comparable basis and that private plans do not profit from enrolling healthier beneficiaries. Traditional Medicare would need authority to offer an integrated benefit package (including drug and supplemental coverage), to update that package in response to changes in the health care system and the insurance market, and possibly to offer various benefit options, such as preferred provider organizations. In addition, the private plans would require substantial regulation; it would be necessary to limit those plans to offering standardized benefit packages (to ensure that benefit packages were not designed to deter sicker individuals) and to preclude them from offering additional services designed to entice healthier enrollees.

In practice, however, securing congressional approval for regulation to do these things would be very difficult (as would monitoring compliance and enforcing the regulations effectively). State insurance regulators believe that the current federal regulatory structure for Medicare private plans does not adequately protect consumers and have called for authority to enforce state laws on marketing practices. [52] Insurers would fiercely resist additional regulation and claim it would impede the workings of the market; the appeal to free-market ideology and the resistance of the powerful insurance industry would make it extremely hard to secure the needed degree of regulation, reporting, and enforcement.

Even in the unlikely event that policymakers could enact a premium support system that ensured fair competition between traditional Medicare and private plans, many other important details would be highly problematic. If the premium support payments failed to keep pace with rising health care costs, beneficiaries — whether they enrolled in traditional Medicare or in private plans — would likely pay steadily higher premiums and cost-sharing charges. Beneficiaries who were sufficiently affluent could afford to pay the higher charges, but beneficiaries of modest means would have difficulty doing so. The ultimate result would likely be a two-tier health care system, in which elderly and disabled people with enough money received full access to needed treatments and medical advances, but those of lesser means found the latest medical innovations to be increasingly out of reach.