Recent policy discussions concerning ways to change Medicaid often include the idea of letting states increase the amounts that low-income beneficiaries are charged in the form of cost-sharing (i.e., in premiums, deductibles, co-insurance, and co-payments). Proponents of increased cost-sharing maintain it would make Medicaid more like private health insurance and promote “personal responsibility,” by making people accountable for a larger share of the cost of their care.

Medicaid already permits cost-sharing on a limited basis. Those who advocate increased cost-sharing generally seek flexibility to raise the amounts that can be charged and to apply cost-sharing to groups of beneficiaries that currently are exempted. Changes in Medicaid’s cost-sharing rules could mean charging higher copayments when a patient sees a doctor or picks up a prescription or charging monthly premiums to participate in Medicaid. This analysis highlights key research about the impact of cost-sharing on low-income families and individuals, including recent evidence about how cost-sharing has affected low-income Medicaid beneficiaries in states that have increased their cost-sharing levels.[1]

Cost-sharing would, by definition, shift a share of Medicaid costs from states and the federal government to Medicaid beneficiaries. Most Medicaid beneficiaries have incomes below the poverty line. Research shows that higher copayments tend to cause low-income people to decrease their use of essential as well as other health care, and can trigger the subsequent use of more expensive forms of care such as emergency room care or hospitalization.

The research indicates that higher copayments can make it harder for people covered by Medicaid to afford medical services they need, while premiums can make it more difficult for low-income people to enroll and maintain coverage. Low-income people with chronic health conditions are the most vulnerable to harm from cost-sharing, as they use the most health care services. (Cost-sharing may also have adverse consequences for health care providers, who may experience a loss of revenue because of reduced utilization of health care or because some beneficiaries cannot afford their copayments or lose eligibility when they cannot pay premiums and seek uncompensated care.)

It is for these reasons that cost-sharing has been limited in Medicaid. Children and pregnant women are exempt from Medicaid copayments by federal law, because they are in a critical developmental stage of life and copayments could create barriers to preventive and primary health care, with long-lasting adverse health consequences. People in nursing homes are exempt because there are other Medicaid mechanisms that ensure they are subject to extensive cost-sharing: all of the income of these people is used to pay for their care, except for a small allowance they are allowed to keep for personal needs (e.g., $30 per month) and an allowance to support a spouse (if there is one) who still resides in the community. For other types of Medicaid beneficiaries, i.e., non-pregnant, non-institutionalized adults, senior citizens and people with disabilities, copayments can be charged but may not exceed “nominal” levels such as $3 per service or prescription.

Within the allowable limits, cost-sharing is very widely used. As of 2003, some 43 states charged copayments to some or all adult, elderly or disabled Medicaid beneficiaries, according to the Government Accountability Office (GAO). Copayments are most frequently charged for prescription drugs but also are often charged for physician, outpatient, inpatient, dental care or other services.[2]

In recent years, many states have increased copayments within the federal limits, and some have received waivers to exceed those limits.

- In 2003, 17 states increased Medicaid copayments;

- 20 states raised them in 2004; and

- Nine states plan to do so in 2005, according to the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured.[3]

Some have argued that copayments should be increased further because Medicaid beneficiaries pay little or nothing for care and do not bear financial responsibility for it. And it has been noted that the federal limits on allowable co-payment charges, such as $3 per service, have not been raised since the 1980’s.

On June 15, the National Governors Association released preliminary policy recommendations on Medicaid reform. Among other things, the NGA recommended a substantial restructuring of current federal cost-sharing rules for Medicaid. NGA’s proposed cost-sharing policy would let states “establish any form of premium, deductible or co-pay” in Medicaid for all populations and all services.

This would give states substantial new discretion to increase cost sharing. The only upper bound on the cost-sharing charges that could be imposed would be a rule that beneficiaries’ total cost-sharing expenses could not exceed 5 percent of family income for people with incomes below 150 percent of the poverty line, and could not exceed 7.5 percent of income (almost one-twelfth of a family’s annual income, or nearly one month’s worth of income) for people with incomes above that level.

The NGA recommendation would permit cost-sharing for the first time for Medicaid beneficiaries such as poor pregnant women and children and also for services such as emergency care. Medicaid currently exempts pregnant women and children from cost-sharing charges to ensure that cost-sharing does not deter the use of primary and preventive care during these key developmental periods of life. Medicaid also exempts services like family planning from copayments to ensure that important preventive services are readily accessible. Most of Medicaid’s low-income beneficiaries, except the “medically needy” and those in Medicaid waiver programs, also are shielded from monthly premiums; premiums have been found to deter enrollment in health insurance by people of limited means. NGA’s proposal appears to erase all of these longstanding protections.

Medicaid already permits small copayments to be charged to poor senior citizens, people with permanent disabilities and other adults. The NGA proposal would allow the amounts of these co-payments to rise rather dramatically. Current Medicaid policy establishes caps of between 50 cents and $3 per service on copayments for most services, in recognition of the fact that most Medicaid beneficiaries live in poverty. The NGA recommendation would let states increase copayments to, for example, $10, $20, or more for each service — and also allow states to charge sizeable monthly premiums to all Medicaid beneficiaries — as long as the aggregate amount that a family was required to pay did not exceed 5 percent or 7.5 percent of its income. An extensive body of research, some of which is summarized in this paper, shows that imposing significant cost sharing on low-income households has been found to have pronounced adverse effects.

In defending NGA’s recommendations in this area, some governors have correctly noted that the Medicaid copayment limits of 50 cents to $3 per service have not changed for many years, while prices have risen. The NGA proposal, however, would permit increases in cost-sharing that vastly exceed the erosion of the current co-payment limits by inflation. In addition, as a recent Center analysis demonstrates, the average out-of-pocket costs that Medicaid beneficiaries bear already are significantly higher as a percentage of income — and have been growing faster in recent years — than the out-of-pocket costs that middle-income people with private health insurance pay.[1]

The NGA has said its Medicaid cost-sharing recommendations are modeled on current SCHIP policy. The policies that apply in SCHIP, however, are not necessarily appropriate for Medicaid since Medicaid serves a significantly poorer population than SCHIP does, and in any case, the increases in cost-sharing that the NGA is proposing go well beyond what SCHIP policy permits. Medicaid primarily serves people with incomes below the poverty live. SCHIP, by contrast, serves children in families with incomes above 100 percent or 133 percent of the poverty line. In addition, a large proportion of those on Medicaid are pregnant women, senior citizens, or people with disabilities or chronic diseases, who often require substantially more medical care than children typically do — and for whom the burdens posed by having to make sizeable co-payments each time a health service is used would accordingly be much greater. In short, the NGA’s proposed increases in cost-sharing could impose substantial hardships on Medicaid beneficiaries, who tend to be both poorer and sicker than SCHIP enrollees.

It also should be noted that the NGA recommendations do not include key beneficiary protections that SCHIP provides. Under SCHIP, children in families with incomes below 150 percent of poverty may not be charged copayments that exceed $5 per service or premiums that exceed $19 per month. The NGA proposal appears to contain no such limitations on the charges that could be imposed on Medicaid beneficiaries with incomes below 150 percent of poverty. In addition, SCHIP prohibits charging copayments or deductibles for preventive health care, while the NGA proposal would permit such charges. Similarly, under SCHIP, cost-sharing may never exceed 5 percent of a family’s income even for those above 150 percent of the poverty line, while the NGA would raise this ceiling to 7.5 percent of income for Medicaid beneficiaries in this income range, thereby setting the ceiling 50 percent higher than the maximum charges that SCHIP allows.

In making these recommendations, the NGA added a caveat that these policies should be monitored and evaluated, and if the evidence shows that access to appropriate health care is being compromised, the policies should be revised. As the review of the research literature presented in this report substantiates, however, this matter already has been extensively studied. There already is compelling evidence that imposing higher copayments on people with low incomes reduces their access to essential health care, with adverse consequences for their health status, and that imposing premiums on low-income people lowers enrollment in public health insurance programs and increases the ranks of the uninsured.

[1] Leighton Ku and Matt Broaddus, "Out of Pocket Expenses for Medicaid Beneficiaries are Substantial and Growing", May 31, 2005.

A new analysis finds, however, that out-of-pocket medical expenses have been rising rapidly for Medicaid beneficiaries — more rapidly, in fact, than for other Americans — and that poor Medicaid beneficiaries actually spend a considerably larger share of their incomes on out-of-pocket medical expenses than do middle-class people with private health insurance.

- For poor adults on Medicaid who are not elderly or disabled, out-of-pocket medical costs rose an average of nine percent per year between 1997 and 2002, roughly twice as fast as their incomes. (2002 is the latest year for which these data are available.) For privately-insured non-elderly adults who do not have low incomes, (i.e., for those with incomes above twice the poverty line), out-of-pocket expenses increased an average of six percent per year over this period.

Out-of-pocket costs have been rising rapidly for Medicaid beneficiaries despite the lack of adjustment in the federal co-payment limits, as a result both of increases in cost-sharing charges by state Medicaid programs (both by states that are operating within the federal cost-sharing limits and to a lesser extent by states that have received waivers to exceed those limits) and increases in the cost of health care services that Medicaid does not cover. (Actions by some states to scale back the services Medicaid covers are a factor here.)[4] - Poor Medicaid beneficiaries aged 19-64 who are not disabled spent an average of 2.4 percent of their incomes on out-of-pocket medical costs in 2002. In contrast, non-elderly adults who have private health insurance and are not low income spent 0.7 percent of their incomes on such costs in 2002, less than one-third as much.

Higher copayments tend to make it harder for low-income patients to access medical care or fill prescriptions. Reductions in medical care or use of medications can, in turn, have adverse consequences, including poorer health and greater subsequent use of high-cost services such as emergency rooms. This is documented by a substantial body of research.

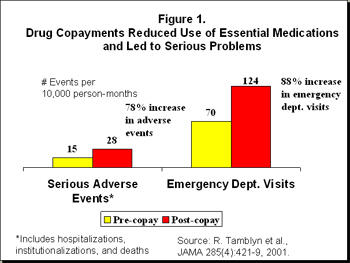

One research study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, studied the consequences of a policy change in Quebec that imposed copayments for prescription drugs on adults receiving welfare. The researchers found that after prescription drug copayments were added, the low-income adults filled fewer prescriptions for essential medications. The copayments led to a 78 percent increase in the occurrence of adverse events, including death, hospitalization and nursing home admissions, apparently because the reduction in the use of essential medications led to poorer health. The copayments also led to an 88 percent increase in emergency room use (see Figure 1).[5] Another peer-reviewed study conducted in the United States found that copayments for substance-abuse services led to initial reductions in treatment costs but ultimately led to higher rates of relapse that required more treatment and drove up long-term costs.[6]

A recent small survey in Minnesota had similar findings. Physicians at Minneapolis’ main public hospital surveyed patients attending medical clinics in mid-2004.[7] Of 62 patients covered by Medicaid or medical assistance, more than half (32) reported that they had been unable to get their prescriptions at least once in the last six months because of copayments of $3 for brand name drugs or $1 for generic drugs. Eleven of the patients who failed to get their medications had 27 subsequent emergency room visits and hospital admissions for related disorders. For example, patients with high blood pressure, diabetes or asthma who could not get their medications experienced strokes, asthma attacks and complications due to diabetes. The inability to afford copayments had serious health consequences and led to the use of more expensive forms of medical care.

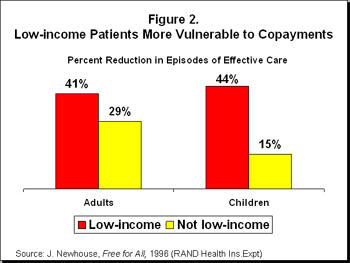

Those with low incomes are more vulnerable to adverse consequences from cost-sharing than higher-income people are, because they have less disposable income and must use much of their limited incomes to meet other basic needs such as food and shelter. This has been documented by rigorous research. The RAND Health Insurance Experiment, considered the definitive study this issue, found that copayments led to a much larger reduction in the use of medical care by low-income adults and children than by those with higher incomes, as seen in Figure 2. Contrary to those who may assume that cost-sharing simply causes people to eliminate “unnecessary” care, the RAND study found that copayments led to reductions in medical care that the researchers rated as being “effective,” as well as in care viewed as being "less effective."

The RAND study found that copayments did not significantly harm the health of middle- and upper-income people but did lead to poorer health for those with low incomes. The study found that among low-income adults and children, health status was considerably worse for those who had to make copayments than for those who did not. (In the RAND study, low income was defined as the lowest third of the income distribution, which is roughly equivalent to being below 200 percent of the poverty line.) For example, copayments increased the risk of dying by about 10 percent for low-income adults at risk of heart disease.[8]

Copayments are particularly challenging for those who have serious or chronic health conditions such as diabetes, cancer, heart conditions or mental illness. Because people with chronic conditions require more medical care and more medications, they must make more copayments.[9] A person who requires five prescription drugs per month must pay five times as much in copayments as someone who has one prescription. Because these individuals also tend to be in fragile health, the consequences of going without a needed service or medication can be severe.

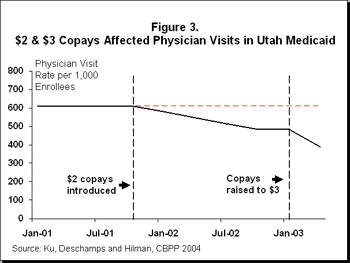

Research has found that when Utah imposed small copayments ($2 or $3 per service or prescription) on Medicaid beneficiaries with incomes below the poverty line, the copayments led to a significant reduction in health care access and utilization (Figure 3). Even though copayments of this size are considered “nominal,” four of ten affected Utahans reported the copayment increases caused “serious” financial hardships.[10] For impoverished individuals and families, copayments as small as $2 or $3 per service evidently can create barriers to accessing some necessary services. To cope with increased health care expenses, about two-fifths of the affected Utahans in the survey reported that they had to resort to coping strategies such as reducing the amount they spent on food or housing or “stretching out” their prescriptions (i.e., taking medications less often than prescribed). Larger copayments would impose greater hardships.

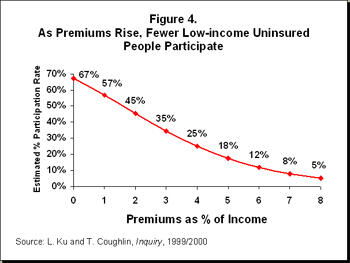

Several states charge monthly premiums to low-income Medicaid or SCHIP beneficiaries. Evidence indicates that premiums reduce Medicaid participation and make it harder for individuals to maintain stable and continuous enrollment. One multi-state study of health insurance programs for low-income people examined participation rates among people who faced premiums of differing levels and found that higher premiums were associated with lower participation. As seen in Figure 4, premiums set as low as 1 percent of a family’s income were estimated to lead to a 15 percent reduction in enrollment. (For example, if 67,000 people are enrolled without premiums, a 1 percent premium would lead to estimated enrollment of 57,000, which is a 15 percent reduction.) Premiums of 3 percent were estimated to reduce enrollment by as much as half.[11]

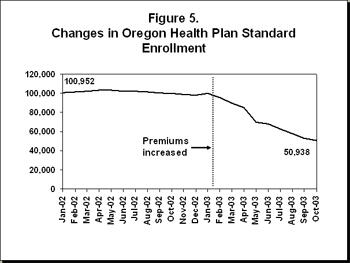

Oregon’s experience is instructive. The state obtained permission through a waiver to increase premiums for its Medicaid expansion program (known as Oregon Health Plan Standard, or OHP). Enrollees included people with incomes below the poverty line. After the state tightened the premium policies, about half of those enrolled — approximately 50,000 people — lost coverage (Figure 5).

Oregon raised premiums to levels ranging from $6 per month for those without any income to $20 per month for people at the poverty line. The state also eliminated the exemption from premiums that it previously had in place for people with no income, and denied enrollment for a period of six months if a person missed or was late in making a single premium payment. The state reduced covered benefits as well, but state researchers concluded that most of the enrollment reduction was caused by the changes in the premiums. About three-quarters of those who dropped from the program became uninsured.[12]

The Oregon experience also provides evidence of the impacts that such a loss of Medicaid coverage can have. Those who disenrolled in Oregon were four to five times more likely to report the emergency room to be their usual source of care than people who remained enrolled.[13] Emergency room use in Oregon’s largest metropolitan hospital increased 17 percent after these changes, although researchers could not isolate the effects of the loss of OHP coverage from the effects of the loss of private insurance that some other Oregonians experienced during the same period.[14] One recent report concluded, however, that there is "strong evidence" that taken together, the OHP changes "resulted in loss of coverage, unmet health care and medication needs, and increased emergency department utilization for the most vulnerable Oregonians."[15]

In fact, concerns about the adverse consequences of premiums on Medicaid or SCHIP enrollment, along with the administrative costs involved, have led a number of states to reconsider and change their policies regarding premiums. Virginia initially imposed premiums on children with family incomes above 150 percent of the poverty line. Upon learning in late 2001 that coverage for approximately 3,000 children would be terminated due to non-payment of premiums, however, then-Governor James Gilmore established a moratorium to keep the children from losing coverage. In 2002, newly elected Governor Mark Warner went a step further and cancelled the premiums, explaining that “Our premiums were actually costing more to administer than the dollars we were receiving, so the team made the case to me that [eliminating the premiums] was both the morally right and the fiscally right thing to do.”[16]

Similarly, Maryland imposed premiums on thousands of children in its SCHIP program, and enrollment declined significantly. In response, the state discontinued the premiums after one year. In addition, Connecticut planned to increase premiums substantially for Medicaid beneficiaries but reversed course and repealed these requirements before they were implemented, after analysis indicated that tens of thousands of people would lose coverage.[17] Finally, Washington state obtained a federal waiver to increase the premiums it charges for children’s insurance, but after more analysis and debate, the state delayed implementation and eventually dropped the premium increases.

Proponents of increased cost-sharing often contend that if Medicaid beneficiaries faced greater cost-sharing like people with private insurance do, they would become more “responsible” and consume less unnecessary care. This argument implies that Medicaid beneficiaries are using unnecessary services at greater rates than people with private insurance. Research shows, however, that Medicaid beneficiaries use approximately the same amount of services as people with private insurance. Two recent studies by Urban Institute researchers found that after controlling for health characteristics, people on Medicaid used the same average amount of care as similar people with private insurance. One study found no statistically significant differences in the number of doctor visits, emergency room visits, hospital stays or dental visits.[18]

In certain situations, Medicaid beneficiaries use more care than privately insured people, but this is a desirable difference. Research indicates that children enrolled in Medicaid are more likely to receive preventive health care, such as well-child visits, than children with private insurance.[19] The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends periodic preventive health visits to monitor children’s health and development and to prevent longer-term illnesses. One likely reason for the beneficial use of preventive services by children enrolled in Medicaid is that children are exempt from copayments under Medicaid. This policy was designed to help ensure that children faced as few barriers as possible to the use of preventive health care. Copayments almost certainly would reduce the extent to which children on Medicaid receive preventive health visits.

Other research has found that while copayments lead people to reduce their use of medical care, copayments do not necessarily make people “smarter” health care consumers. When higher copayments are imposed, patients reduce their use of both essential and less-essential services.[20] For example, a recent study of tiered drug copayments in the private sector (in which copayments are set higher for some medications than for others) found that higher copayments led diabetics to reduce their use of diabetes medications.[21] Another study found that increased copayments led to reductions in patients’ use of drugs for high blood pressure (ACE inhibitors) and cholesterol reduction (statins).[22] When patients reduce their use of important chronic-disease medications because of higher copayments, their diseases can progress and lead to more severe consequences such as heart attacks.

Charging patients higher copayments also may be ineffective in motivating consumers to choose less expensive drugs since it is physicians, not consumers, who select the medications to prescribe. When they are writing prescriptions, physicians often do not know which insurance plans patients have or which drugs have higher or lower copayments under each insurance plan. They often lack the knowledge and financial incentive to prescribe a drug with a lower copayment. If a physician prescribes a medication with a higher copayment, the patient may have little choice but to pay the higher price or do without the medication. For low-income patients, the consequences are more serious because they are less able to afford copayments.

Some states have sought to increase cost-sharing limits in Medicaid. At the same time, states have urged the federal government to avoid reducing federal Medicaid expenditures by shifting costs to states. State officials may want to consider whether it is appropriate to shift costs to low-income beneficiaries by significantly raising cost-sharing charges or limiting covered benefits. That would not only place heavier financial burdens on poor families and individuals but could jeopardize the ability of such people to access health services and risk ultimately impairing their health.

The problems created by higher cost-sharing may extend beyond beneficiaries to other parts of the health system. To the extent that premiums cause low-income people to lose Medicaid coverage and become uninsured, or that copayments cause patients to avoid obtaining medical care or filling prescriptions, this could lead to increased use of emergency rooms or safety-net clinics. In addition, when Medicaid patients can not afford their copayments, this can create a revenue loss for health care providers, including pharmacies.

It is important to encourage efficient and cost-effective care in Medicaid. Cost-sharing, however, is a blunt tool that can discourage essential and appropriate care and can create barriers to health care for those in need. It is important to remember that the current cost-sharing protections in Medicaid exist precisely because the program’s beneficiaries generally have incomes well below the poverty line and a substantial proportion of them have health conditions that could be compromised by excessive cost-sharing.