- Home

- The Long-Term Fiscal Outlook Is Bleak

The Long-Term Fiscal Outlook Is Bleak

Restoring Fiscal Sustainability Will Require Major Changes to Programs, Revenues, and the Nation’s Health Care System

Summary

This report updates the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ projections of federal spending, revenues, deficits, and debt through 2050. These projections — like the projections the Center issued in January 2007 and the projections by other institutions such as the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), Government Accountability Office, and Office of Management and Budget — show that without changes in current policies, federal deficits and debt in coming decades will grow to unprecedented levels that will threaten serious harm to the economy.

We are not suggesting that the long-term budget problem should take precedence over short-term steps to stabilize financial markets and the economy. Such steps — even if deficits exceed $1 trillion this year and next — are necessary to help avert a deep and prolonged recession. In fact, one important conclusion of this analysis is that the increases in the deficit caused by the current recession and various measures to bring it under control will have only a small effect on the long-term deficit problem, assuming that the severity of the recession does not greatly exceed current expectations.

This conclusion should not be surprising. The costs related to the recession will have only a small budgetary impact on the long-term deficit problem, because they are temporary. Temporary costs — even if very large in the short run — add much less to the long-term fiscal gap than permanent costs (such as extending the tax cuts) because their total costs are small relative to the total size of the economy over the long-run. Also, short-term economic weaknesses have little impact on the major drivers of the long-term fiscal imbalance: rising health care costs and the aging of the population.

Nevertheless, policymakers should keep the long-term budget problem in mind as they take the necessary steps to stabilize financial markets and the economy. While the long-term problem should not deter policymakers from dealing with the short-term crisis, policymakers will need to demonstrate to the public and the lenders who finance our short- and longer-term borrowing needs that they are prepared to move the budget toward a sustainable long-run path when the economy improves.

In addition, in designing policies to deal with the short-term problems, policymakers should consider policies that could serve “double duty” by helping to spur the economy in the short term while also laying the groundwork for measures to restore fiscal responsibility in the longer term. This includes measures such as investments in health information technology that hold promise for contributing to efforts to stem the rapid growth of health care costs over time.

The report’s principal findings are:

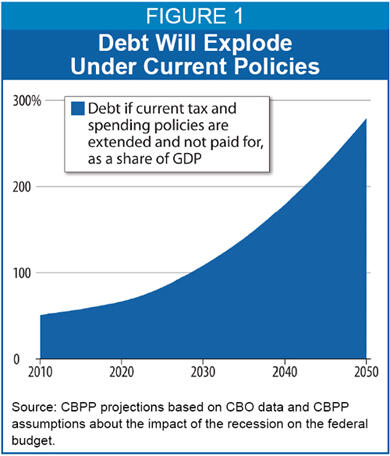

- Deficits and debt are headed for dangerously high levels. If we continue current policies, the federal debt will skyrocket from a projected 46 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) at the end of fiscal year 2009 to 279 percent of GDP in 2050. That would be more than two and a half times the existing record (which was set when the debt reached 110 percent of GDP at the end of World War II) and would threaten serious harm to the economy. (See Figure 1.) In addition, under current policies, the annual budget deficit is projected to reach approximately 21 percent of GDP by 2050.

Deficits and debt are projected to grow this much because expenditures will rise as a share of GDP between now and 2050, while revenues will fall. Without policy changes, we project that program expenditures will increase from 19.2 percent of GDP in 2008 to 24.6 percent in 2050. We project that revenues will decline to 17.2 percent in 2050 — well below the average for the last 30 years (which is 18.4 percent of GDP). Moreover, the federal budget was balanced only four times in those 30 years, and in each of those years, revenues were between about 20 percent and 21 percent of GDP.

- Preventing a debt explosion will require difficult choices. The “fiscal gap” — or the average amount of program reductions or revenue increases that would be needed over the next four decades to stabilize the debt at its 2009 level, as a share of the economy — equals 4.2 percent of projected GDP. Eliminating that gap would require the equivalent of an immediate and permanent 24 percent increase in tax revenues or an immediate and permanent 20 percent reduction in expenditures for all federal programs. Given the size of the fiscal gap, some combination of revenue increases and program cuts will be needed.

- Rising health care costs are the single largest cause of rapidly rising expenditures. The main sources of rising federal expenditures over the long run are rising costs throughout the U.S. health care system (both public and private) and the aging of the population. Together, these factors will drive up spending for the “big three” domestic programs: Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. Health care costs are by far the biggest single factor. For the past 30 years, costs per beneficiary throughout the health care system have been growing approximately 2 percentage points faster per year than per-capita GDP, and our projections assume this pattern will continue through 2050. Limiting health care cost growth to 1 percentage point faster than per-capita GDP growth would shrink the fiscal gap by more than one-third (to 2.7 percent of GDP). If health care costs could be constrained to grow only at the same rate as per-capita GDP — a daunting and probably unachievable goal — the fiscal gap would shrink by more than two-thirds, to just 1.2 percent of GDP.

- Fundamental health care reform must be part of any solution. Rising costs throughout the health care system exacerbate the long-term budget problem in two ways. They increase federal spending by raising the per-person cost of providing health care through Medicare and Medicaid. (Per-person costs are rising in these programs at about the same rate as in the health care system as a whole, including the public and private sectors.) In addition, rising health care costs shrink federal revenues by increasing the share of the nation’s income that is exempt from taxation. Employer-provided health benefits are excluded from taxable income, and various other provisions of the tax code allow individuals to pay some health care costs from pre-tax income. Thus, when health care costs grow faster than the economy, the share of total income that is exempt from taxation increases.

A major effort is needed to expand our currently limited knowledge about ways to reduce the rate of growth in heath care costs in the public and private sectors alike, while improving the quality of care system-wide. Medicare can play an important role in these efforts, and policymakers should promote initiatives that both restrain cost growth in Medicare and serve as a model for reforms applicable to the system as a whole. Examples include eliminating the large overpayments that Medicare makes to private insurance companies that participate in the Medicare Advantage component of the program, altering Medicare’s payment systems to reward quality and efficiency, and strengthening primary care and care coordination. - Upcoming tax policy decisions will have a major impact on the size of the problem. Policymakers could shrink the fiscal gap by almost half — from 4.2 percent of GDP to 2.3 percent — by allowing the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts to expire as scheduled at the end of 2010 or by offsetting the cost of extending those tax cuts they choose to extend. This is because the budgetary benefits would start almost immediately (in 2011), and those benefits would reduce projected interest payments on the national debt by a growing amount over time. But even if Congress were to allow the tax cuts to expire or to offset the full cost of extending them — steps that are extremely unlikely — the budget would still remain on an unsustainable long-run path.

- The recession and other government programs are not major long-term factors. The current recession will enlarge the long-term fiscal imbalance only very modestly. Our projections take into account the substantial expenditures that Congress has approved or is expected to approve to help revive financial markets and to stimulate the economy. They also take into account the fact that this recession, like previous ones, will reduce tax revenues and cause automatic increases in expenditures for programs such as unemployment insurance. Yet 96 percent of the projected long-term fiscal problem would exist even without these added costs.

Also of note, total spending for all federal programs other than Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security — as well as total spending for all federal entitlement programs other than these three — are projected to shrink as a share of the economy in coming decades. Since these programs will consume a smaller share of the nation’s resources in 2050 than they do today, they do not contribute to the long-term fiscal problem. Statements that we face a general “entitlement crisis” thus are mistaken.

The bottom line is that, as the economy recovers, policymakers should begin to implement a balanced approach to addressing the nation’s long-term imbalance, through a combination of reform of the U.S. health care system, reductions in federal expenditures, and increases in federal tax revenues.

(16pp.)

More from the Authors