- Inicio

- Testimony: LaDonna Pavetti, Director Of ...

Testimony: LaDonna Pavetti, Director of Welfare Reform and Income Support, on the Impact of the Recession and the Recovery Act on Social Safety Net Programs

Before the House Budget Committee

Thank you for the opportunity to testify today. My testimony will focus on four points:

- Poverty was high at the start of the recession and it is likely to remain high for an extended period. Some of the most effective measures to boost employment (and reduce poverty) in a weak economy have and will continue to be those that provide financial relief to people struggling to make ends meet and to states facing large budget shortfalls.

- The recovery act passed in February has kept this serious recession from being even worse. It has not only moderated the decline in GDP and increase in unemployment, but also prevented millions of Americans from falling into poverty and has helped some states to forgo significant cuts that would have weakened the safety net for very poor families with children.

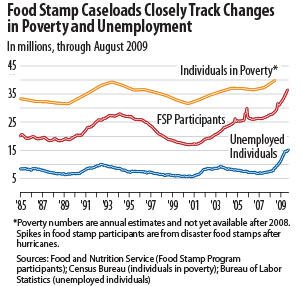

- The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly food stamps, has responded quickly to rising need in all states, but the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance program has lagged behind and has been moderately or substantially responsive in only 20 states.

- To help ease hardship and avoid short-circuiting an economic recovery, Congress will need to adopt policy solutions that are responsive to both immediate needs and the long-term consequences of the recession.

Recent and Historical Data on Poverty and Incomes Underscore Challenge

Recent Census Bureau data show that the nation lost substantial ground in 2008 on poverty and incomes. The number of people living in poverty jumped by 2.6 million, to 39.8 million people. The poverty rate rose to 13.2 percent, the highest since 1997. Real median household income declined 3.6 percent, the largest single-year decline on record, and reached its lowest point since 1997.

History suggests that the road to recovery from the current economic crisis will be long. Unemployment has been slow to recover after recent recessions, and poverty even slower. In the recession of the early 1990s, unemployment did not peak until 15 months after the recession ended. In the 2001 recession, unemployment did not peak until 19 months after the recession ended. Poverty often takes even longer to start its recovery. After each of the last three recessions, poverty continued rising or failed to decline in the first year after unemployment began to fall:

- In 2004, the first year the annual unemployment rate declined following the 2001 recession, the poverty rate rose to 12.7 percent, up from 12.5 percent the year before. The number of poor persons rose 3.3 percent or 1.2 million.

- In 1993, the first year the annual unemployment rate declined following the 1991 recession, the poverty rate reached 15.1 percent, not statistically different from the prior year’s 14.8 percent. The number of poor persons rose a statistically significant 3.3 percent.

- In 1983, the first year the annual unemployment rate declined following the 1981-82 recession, the poverty rate reached 15.2 percent, not statistically different from the prior year’s 15.0 percent. The number of poor persons rose a statistically significant 2.5 percent.

The pattern suggests that poverty could take years to start falling, and even longer to return to its pre-recession levels. These figures are particularly grim because they come after the disappointing record of the 2001-2007 expansion. Poverty was actually higher — and median income for working-age households lower — at the end of that expansion than during the 2001 recession. Since the nation began collecting these data, such a dismal record during an expansion has never occurred before.

These data include only the early months of the recession. The figures for 2009, a year in which the economy has weakened further and unemployment has climbed substantially, will almost certainly look worse. The figures may worsen again in 2010 if unemployment rises somewhat further or even if it plateaus, as a growing numbers of individuals who are currently unemployed may exhaust their unemployment benefits during 2010 before they find new jobs. However, the expected increase in poverty would be substantially greater if not for the responsiveness of the social safety net and the additional assistance provided by the American Recovery and Re-Investment Act of 2009 (ARRA).

Recovery Act Keeping Millions of Americans Out of Poverty and Helping Forestall Cuts in Critical Human Services

The recovery act’s primary goal was to help the broader economy, and evidence suggests it is having a significant positive impact. The Congressional Budget Office estimated in November that in the third quarter of calendar year 2009, “an additional 600,000 to 1.6 million people were employed in the United States, and real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP) was 1.2 percent to 3.2 percent higher, than would have been the case in the absence of ARRA.”[1] CBO estimated this spring that “The boost to total employment [because of the recovery act] peaks at about 2 ½ million jobs in the second half of 2010.”[2] In addition, the recovery act has had the important secondary effect of significantly ameliorating the recession’s impact on poverty.

Seven ARRA Provisions Keep 6.2 Million Americans Out of Poverty

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities recently examined seven provisions of the recovery act that provide direct assistance to individuals — including three tax credits for working families, two improvements in unemployment insurance, expanded nutrition assistance, and one-time payments to senior citizens, veterans, and people with disabilities — and estimated that these provisions will result in 6.2 million fewer Americans (including 2.4 million children under 18) being counted among the nation’s poor in 2009.[3] Because the government’s official measure of poverty considers only cash income and would therefore miss many of the tax-based and non-cash income supplements in the recovery act, our analysis used a broader poverty measure recommended by the National Academy of Sciences.

Two provisions included in our analysis, the new Making Work Pay Credit and the increase in SNAP benefit levels, kept the largest number of individuals out of poverty. The Making Work Pay Credit, which provides a tax credit of $400 for workers earning up to $95,000 ($800 for a couple earning $190,000) kept 1.6 million individuals, (including 500,000 children) out of poverty. The 13.6 percent increase in SNAP benefit levels kept 1.1 million individuals out of poverty, including 500,000 children.

The increase in SNAP benefit levels illustrates the important role that provisions aimed at addressing economic hardship can play in stimulating the economy. This provision was included in ARRA to provide a very fast and effective economic stimulus that could help to push against the tide of economic hardship that low-income individuals are facing. Te increase went into effect in April 2009. Through September 25th, according to USDA, it had provided about $4.5 billion in federal support to low-income households across the country.

The added SNAP benefits ripple through the economy. When a family uses its SNAP benefits to shop at a local grocery, this helps the grocer pay his or her employees and purchase more from his or her suppliers. That, in turn, helps the suppliers pay their employees (as well as the truckers who deliver their products), and so on. Based on analysis from USDA’s Economic Research Service, the $4.5 billion temporary increase in food stamp benefits has resulted in a total of about $8 billion in total economic stimulus.

The estimates from our analysis represent only a fraction of the overall impact of the recovery act on poverty because the seven provisions we included account for only about 26 percent of the act’s total funding. We were unable to model billions of dollars in assistance that would further reduce the number of Americans in poverty. These include Pell grants and education tax credits, funding for state health insurance programs, child care, child support enforcement, and assistance to homeless individuals and to TANF recipients.

State Fiscal Relief Helps States Continue to Provide Critical Services and Avoid Layoffs

ARRA included about $140 billion to provide fiscal relief to states. This funding, provided to states through enhanced funding for Medicaid and a Fiscal Stabilization Fund targeted primarily to education, has helped states substantially. Without it, both state budget cuts and state tax increases would be much larger. The best estimates suggest that the fiscal relief in ARRA has allowed states to close 30 percent to 40 percent of their budget gaps this year. Without this aid, states would have been forced to institute even more severe actions that would have placed a greater drag on the economy.

State fiscal relief helps to mitigate the impacts of the recession through several different means. It helps states continue to provide critical services and it helps them avoid layoffs of public employees. It also prevents the contraction of private sector economic activity and the loss of private-sector jobs in firms that supply goods and services to state governments or that sell their products to state employees who would otherwise be laid off, or to people who otherwise would have less purchasing power because, in the absence of fiscal relief, state programs they rely on would be cut or their taxes would be raised.

The temporary increase in the share of the Medicaid program paid by the federal government (known as the Federal medical Assistance percentage or “FMAP”) has provided states with additional funding to cover the costs of providing Medicaid for low income families. The maintenance of effort requirement associated with the enhanced funding has protected Medicaid eligibility criteria –- and more people cast into the ranks of the uninsured–- to cover state budget shortfalls. Similarly, a portion of the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund was dedicated to helping states and localities maintain K-12 and higher education funding. To receive the funding states had to fund K-12 and higher education at no less than the fiscal year 2006 level in fiscal years 2009, 2010, and 2011.

The ARRA funding for state fiscal relief has been effective at creating and preserving jobs. Economist Mark Zandi has found that a temporary increase in state and fiscal relief has a high “multiplier effect,” meaning that every $1 spent by the federal government results in a $1.41 increase in the gross domestic product. The Department of Education found that more than 255,000 education jobs and nearly 63,000 jobs in other areas have been retained or created through the Fiscal Stabilization Fund, for a total of 318,000 jobs saved or created through September 30 by the Fiscal Stabilization Fund.[4]

No official reports are available on the jobs impact of the fiscal relief funding provided through Medicaid, but there is little question that the Medicaid funding has resulted in the retention or creation of both public and private-sector jobs for health providers, in large part because more people remain insured than would have been the case without the funding. The President’s Council of Economic Advisers looked at the first six months of ARRA Medicaid funding and found a strong relationship between that funding and jobs. [5]

TANF Emergency Contingency Fund Helps States to Forestall Cuts in Benefits and Provide Cash Assistance and Subsidized Jobs to More Families

Congress included $5 billion in the recovery act for a TANF Emergency Contingency Fund (ECF) to provide states with additional resources to help families meet their basic needs. States can qualify for these funds if they provide cash assistance to more needy families with children, spend more to provide one-time non-recurring benefits to help families stave off a crisis, or create subsidized employment opportunities for jobless individuals. Over $1 billion in Emergency Funds have already been authorized with about two-thirds of this amount based on increased spending on TANF basic assistance. States are still in the process of submitting requests for these funds — and it is too soon for states to apply for funds for the last half of 2010 — so we don’t yet know how much of the $5 billion they will use and what the overall impact on poverty will be. However, we do know that this fund has made it possible for some states to meet the increased demand for assistance, to avoid significant cuts in cash assistance and services for very poor families with children and to maintain their commitment to providing work opportunities for TANF recipients. Below are examples of how three states —Oregon, Florida and Maryland — are planning to use these funds. Between March 2008 and March 2009, these state’s TANF caseloads increased by 27, 14 and 13 percent, respectively.

- Anticipating that it will be able to draw down $74.9 million from the TANF ECF for 2009 and 2010, Oregon expects to cover the costs of providing cash assistance to an average of 6,226 more families per month and to forestall cuts that would significantly weaken the safety net for poor families. Without this additional funding, Oregon would have eliminated its TANF program for unemployed two-parent families, reduced eligibility for employment-related day care, further reduced transitional payments for newly employed parents, and eliminated enhanced grants for families with a disabled household head applying for Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance.

- Florida expects to draw down at least $76 million to cover the costs associated with providing cash assistance to an average of an additional 6,406 families each month. The state expects to draw down $5.4 million to provide subsidized temporary employment for unemployed individuals. For example, a county that lost 1,200 jobs due to a plant closing plans to use a portion of the funds to provide subsidized employment to 75 individuals who would otherwise be unemployed.

- Maryland expects to qualify for over $30 million in TANF Emergency Funds for 2009 and for additional funds for 2010. This includes $17.7 million in basic assistance used to provide cash benefits to an average of an additional 3,107 families each month, and $12.5 million used provide non-recurrent short-term benefits such as emergency assistance payments to families who might otherwise lose their current housing or be unable to stay employed. Maryland plans to use some of these funds to cover the additional staff costs associated with processing a greater volume of applications for assistance.

Additional funding to create or expand subsidized employment programs has been authorized for over a dozen states. These programs will provide jobs for low-income individuals who would otherwise be unemployed. Rigorous evaluations of similar programs have shown they are successful at providing short-term employment opportunities when parents are unable to find unsubsidized jobs on their own.[6]

- California is planning to draw down $300 million from the TANF ECF to create subsidized employment programs throughout the state. San Francisco is planning to use its share of funds to expand its JOBS NOW! program to provide subsidized employment to an additional 1,000 unemployed and underemployed parents by September 2010. Participants will undergo a vocational assessment to determine their skills and interests, after which they will be assigned to an appropriate job based on their employment readiness and the level of personal support needed. Los Angeles is implementing the state’s largest program with plans to provide subsidized employment to 10,000 unemployed individuals.

- New York provides another example. The state is currently implementing a $39 million effort to provide three different types of subsidized employment opportunities to unemployed individuals. The state will spend $25 million to create a new Transitional Jobs Initiative to provide paid, subsidized work experience — combined with educational opportunities related to work— to TANF-eligible individuals including disconnected youth and the formerly incarcerated. The state will spend $7 million to create a Health Care Job Subsidy Program that will hire health care outreach workers to help low-income individuals maintain eligibility for public health care programs and to connect them to other preventative health care services. Finally, the state will spend $7 million to create a new Green Corp Jobs Subsidy program that links eligible individuals to job skills training, basic education, and career advancement opportunities in entry-level, high-growth energy efficiency and environmental conservation industries. The Health Care and Green Jobs programs each include $2 million of money from New York’s general fund to provide subsidized employment opportunities to single individuals receiving cash assistance from the state’s general assistance program. New York also increased its wage subsidy program by $10 million to make it a $14 million program. The state will spend a total of $53 million from ARRA and the general fund to create subsidized employment opportunities for unemployed low-income individuals.

ARRA Child Care Assistance Helping Working Families Afford Child Care

Congress recognized the vital importance of child care assistance in helping low-income families obtain jobs and remain in the workforce by including $2 billion for the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) as a part of the recovery act. CCDBG is the largest federal source of funding to states for child care assistance and serves children birth through age 13. ARRA child care funds are one-time funds to help states recover from the economic crisis by creating new jobs and serving more families. Like the TANF Emergency Contingency Funds, the CCDBG ARRA funds are available until September 30, 2010.

As of mid-November, states, territories, and tribes had drawn down a total of $244.8 million in child care funds, or 12.3 percent of the $2 billion allocation. States are beginning to accelerate their draw down rate now that they have an understanding of federal reporting requirements, and have approved state plans. States report to the Child Care Bureau that they are spending the money in the following ways:

- Reduce waiting list or avoid service cuts (11 states)

- Increase payment rates (11 states)

- Provide assistance during an extended period of job search (10 states)

- Lower copayments (4 states)

- Improve child care quality (41 states)

SNAP Responding Quickly and Systematically to Rising Need

SNAP benefits also help protect the economy as a whole by helping maintain overall demand for food during slow economic periods. In fact, SNAP benefits are one of the fastest, most effective forms of economic stimulus because they get money into the economy quickly.

Uneven Responsiveness of TANF Cash Assistance Caseloads

In most states, TANF cash assistance programs have lagged far behind SNAP in their responsiveness to the economic crisis and to rising poverty. The state variation is significant. Nationally, the total number of families with children receiving cash assistance remained essentially flat between March 2008 and March 2009; the SNAP caseload increased by 19 percent during this same period, reflecting large increases in poverty. TANF caseloads either have not been responsive at all to the economic downturn or have been only minimally responsive in 31 states; caseloads declined in 13 of these states, remained essentially flat in eight and increased by one to five percentage points in ten. Caseloads responded moderately in another 14 states, increasing by between 6 and 15 percent. Caseloads increased by more than 15 percent in only six states: New Hampshire, New Mexico, Oregon, South Carolina, Utah and Washington.

The lack of responsiveness of the TANF caseload, which is striking when compared to the surge both in unemployment and in SNAP caseloads, is likely attributable to several factors. For the last 13 years, states have been focused on reducing their TANF caseloads for a variety of reasons —fiscal, ideological, and as a measure of effective performance— and even during the current economic crisis, states have been slow to shift away from this emphasis. It is important to note that even prior to the economic downturn, TANF was not accessible to many families who needed it. In 2005, the TANF cash assistance program served only about 40 percent of eligible families compared to 80 percent of eligible families in 1995. Many states have policies and procedures in place that make it difficult both for eligible applicants to obtain benefits and for recipients to continue receiving benefits even if they continue to be eligible. Some states require applicants to participate in work activities for a period of time before they can qualify for aid, but some families may be in crisis and have difficulty in meeting these requirements until they begin to receive help in meeting basic needs. Many states have eased their enrollment processes for SNAP and Medicaid but have not extended these improvements to TANF; others actively discourage TANF applicants. In some cases, families in need may not pursue TANF because of stigma, erroneous information about eligibility, time limits or other reasons.

Increasing the Responsiveness of the Safety Net and Responding to the Long-Term Consequences of the Recession

Although the recovery act has provided significant help to many low-income families, more needs to be done. Serious challenges will remain for the next several years, and they demand a continuing response. Some of the most effective measures to help the ailing economy are those that provide fiscal relief to people struggling to make ends meet and to states facing large budget shortfalls. Congress should consider the following actions to increase the responsiveness of the safety net and to respond to the long-term consequences of the recession. I divide my recommendations into two categories, short-term actions that should be taken before the end of 2009 and longer-term actions that should be taken by the end of the current fiscal year.

Short-term actions

- Provide additional funding to states to help them handle the staffing costs of responding to greatly increased numbers of jobless households applying for food stamps. SNAP caseloads are at an all-time high and are continuing to rise. States are increasingly unable to handle the increased workload associated with enrolling more people in the program. Many states, facing budget crises that stem from the economic downturn, are cutting staff across large numbers of state agencies including food stamp administration. Other states are achieving reductions by freezing all new hiring and leaving open positions unfilled. (States normally pay 50 percent of the costs of administering the SNAP program.) Very large backlogs and bottlenecks are showing up in a growing number of areas across the country, with long waits for application interviews and delays in application processing.

Additional funding to help states cover administrative costs will get help into the hands of people that qualify for it more quickly. It will also increase jobs in two ways — both directly by employing more state staff, and indirectly by getting food stamps into the hands of eligible families more promptly. The current backlogs are reducing the effectiveness of the investment Congress made in the ARRA legislation in temporarily expanding food stamp benefits. ARRA provided $290.5 million in administrative funds to states to help them manage rising caseloads through 2010. An additional $300 to $500 million over the next two years would help states provide SNAP benefits to the growing numbers of families affected by the economic downturn. We also recommend a maintenance-of-effort provision, perhaps at 97 percent of state spending on basic state SNAP administrative costs in fiscal year 2008, to prevent states from substituting the new funds for existing state SNAP administrative funding.

- Provide states with additional resources to provide cash assistance payments, emergency assistance and subsidized employment to low-income families beyond the September 30, 2010 deadline. The ARRA TANF Emergency Fund has provided states with additional resources to cover 80 percent of the costs of providing TANF cash assistance payments, one-time emergency payments and short-term subsidized jobs to more families. The TANF block grant has been frozen for 13 years. When the TANF program was established in 1996 as a block grant, a TANF Contingency Fund was created as part of the new program and funded so that it would be available for states to draw upon in an economic downturn. The Contingency Fund lasted for 13 years, but it will be depleted this quarter, because more states have drawn down these funds recently due to the severity of the downturn.

As currently structured, neither the regular TANF Contingency Fund nor the ARRA TANF Emergency Fund will provide states with the resources they need to support low-income families through a long recovery. ARRA provided $5 billion for a new, temporary TANF Emergency Fund, and some funding remains in it, but that funding expires on September 30, 2010. Without an early signal that additional funding will be available, states will include cuts to their TANF basic assistance programs in their budgets for FY 2011 and they will not expand existing or create new subsidized employment programs if they believe such programs will need to be dismantled within six to nine months.

There are two options for addressing this problem. First, the ARRA TANF Emergency Fund could be extended for one or two more years, or it could be made permanent and replace the TANF Contingency Fund. Second, the TANF Contingency Fund could be refunded and restructured to build on the ARRA TANF Emergency Fund model which does a better job at providing extra resources directly to families.

- Phase down state fiscal relief more gradually. Despite improvements in the economy as a whole, state fiscal conditions for state fiscal years 2011 and 2012 look as bad as those for 2009 and 2010. We estimate that state deficits in state fiscal year 2011 will be about $180 billion, some $40 billion of which states will be able to close with recovery act funds. For state fiscal year 2012, we project state budget deficits of $120 billion, with essentially no recovery act funding available to reduce the deficits.

One strategy to address these shortfalls is to provide a reduced level of federal stimulus (through some combination of the enhanced FMAP provision and the Stabilization Fund) to states for a period of time beyond December 31, 2010, when the current recovery act funding ends. Congress could, for example, provide additional funding targeted to states in serious economic and fiscal distress to close a portion of projected state shortfalls in 2010-2011 and 2011-2012. States would still need to close the majority of the shortfalls, themselves. In this way, federal assistance would phase out gradually rather than ending abruptly after December 31, with adverse consequences for both vulnerable families and the U.S. economy.

It would be helpful to send a signal soon about whether additional funding will be available, since the new budget cuts and tax increases the states will institute to balance their 2011 budgets will take effect next summer or even earlier. (State fiscal year 2011 begins on July 1, 2010 in most states, and the budget planning process begins long before that). Unless states know that additional federal aid is coming, they will begin cutting spending and raising taxes by July to close the shortfalls in their fiscal 2011 budgets. The large resulting state budget cuts and tax increases would counteract a sizeable share of the federal stimulus and heighten the risk of a double-dip recession. These state actions could result in a loss of 900,000 jobs and reduce demand by as much as $260 billion over the next two fiscal years, threatening to place a serious drag on the economy and weaken the recovery. One state has announced that when ARRA funding expires, it will cut almost 80,000 individuals from its Medicaid programs and other states are expected to pursue similar actions in the coming months.

- Prevent the income limits for CHIP, Medicaid, free school meals, food stamps, and other programs from being lowered amidst a severe economic downturn. Unless Congress passes legislation that keeps the poverty eligibility threshold constant next year, the income limits for low-income programs that tie their income limits to the poverty line (or a multiple of it) are set to drop. A comparable provision is in place with respect to the Social Security Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA). Were it not in place, Social Security benefits would be lowered in 2010 to reflect a negative cost-of-living-adjustment rather than staying constant.

If income limits for poverty programs are not held constant, the poverty eligibility threshold for a family of four will fall from $22,050 to an estimated $21,850 in January 2010. The poverty threshold for a single individual, such as an elderly widow living alone, will fall from $10,830 to an estimated $10,690. We estimate this will cause 40,000 to 45,000 households to be cut off food stamps alone (or not to be allowed on the program in the first place). The number of families or children losing eligibility for other programs such as Medicaid and CHIP, free school lunches, and the like also will run into the tens of thousands. This issue can be addressed by freezing the new poverty guidelines for program eligibility, which HHS will issue in January, at their 2009 level. Cutting struggling families off these programs in a weak economy would not represent sound economic policy, since affected households will have to cut their purchases. It also would cause significant hardship. A simple freeze of the HHS poverty guidelines would solve the problem.

- Renew the Emergency Unemployment Compensation program. Last year, Congress created the Emergency Unemployment Compensation program, which currently provides additional weeks of federally funded unemployment benefits to unemployed individuals who have exhausted their regular state benefits. (Congress has created a similar program in every recent recession.) The recovery act expanded this program and extended it through December 2009. This and other unemployment insurance provisions in the recovery act have helped millions of unemployed workers weather the recession better than they otherwise would have. The additional weeks of benefits are also one reason why the recovery act has kept the decline in economic activity from being even worse in this recession. With unemployment expected to remain very high throughout 2010, Congress should extend the EUC program and the other UI provisions created by the recovery act for another year. The need for an EUC extension is especially great given the record level of long-term unemployment, since these are the workers the program assists.

- Help unemployed families maintain health insurance coverage. Recognizing that some unemployed workers would not have sufficient financial resources to continue their health insurance coverage through COBRA, Congress included a provision in the recovery act that provides for premium reductions and additional election opportunities for health benefits under COBRA. This provision allows individuals to pay 35 percent of their COBRA premiums, with the remaining 65 percent being reimbursed through a refundable, advanceable tax credit. This provision is set to end this month, as well. Given that unemployment remains high, this provision should be extended for another year. States should also be allowed to provide temporary health insurance coverage through Medicaid for workers who become unemployed during the recession, such as those who are not eligible for COBRA or cannot afford the remaining COBRA premiums. The federal government would cover the full cost of the coverage through 2010. Such a proposal was included in the House-passed version of the recovery act.

Longer-term actions

- Use TANF Reauthorization as a vehicle to improve TANF’s responsiveness during economic downturns and improve its performance as an employment program for low-income parents. TANF cash assistance programs aim to serve two different functions: (1) to provide a safety net during times of family crises and when jobs are not available, and (2) to help low-income parents find and maintain employment. Under the program’s current structure, these two functions often are at odds with each other, particularly when unemployment is rising and jobs are hard to find. In addition, the current performance standards discourage states from providing assistance to families most in need. When TANF is reauthorized next year, Congress should identify improved performance measures that encourage states both to provide a safety net for very poor families when they need it and to help them improve their long-term employment outcomes. It should also encourage state innovation and provide states with additional funding to improve the employment prospects of the families least likely to succeed in the paid labor market on their own. Adequate child care funding should also be provided to increase parents’ chances of achieving long-term success in the paid labor market.

- Make tax credits expansions included in ARRA permanent. ARRA expanded eligibility for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the low-income component of the Child Tax Credit (CTC) and the American Opportunity Tax Credit. The ARRA expansions made very low-income working families with nearly 3 million children eligible for the CTC for the first time, and families with 10 million additional children eligible for a larger CTC. The ARRA expansions also provide larger EITC payments to low-income families with three or more children and married families. ARRA also made it possible for low income families who do not earn enough to owe income taxes to qualify for up to $1,000 per year through the American Opportunity Tax Credit to help defray college tuition costs. These changes will expire at the end of 2010, if Congress does not pass a law implementing the presidents’ proposal to make them permanent. We estimate that the EITC and CTC expansions have lifted more than 900,000 people, including 600,000 children out of poverty. If these changes are not made permanent, these individuals will fall back into poverty.

- Pass the Hunger Free Schools Act (H.R. 4148 and S. 1343). The number of children in poverty and struggling against hunger is increasing. The federal child nutrition programs have an important role to play in making sure that low-income children have access to nutritious food. The Hunger Free Schools Act would help ensure that poor children receive the free school meals for which they are eligible and that they are enrolled with much less paperwork. The bill would allow schools in very poor neighborhoods to provide free meals to all their students. Instead of spending time and resources sorting through applications from very poor children, these schools could focus on serving healthy meals to all students. Nationwide, an estimated 6,000 schools (under the Senate version of the bill) to 12,000 schools (under the House version), serving roughly 3 to 6 million children, could qualify for this new option. Also, to help poor children receive free meals no matter where they attend school, the bill would require schools to use data already collected and scrubbed by Medicaid to enroll children for free meals automatically if their income is below 133 of the poverty line. An estimated 3 million children would benefit (some of these children would benefit from the simplification of automatic enrollment, others would be enrolled for free meals for the first time). These proposals should be priorities for the reauthorization of the child nutrition programs because they would improve access to free meals and are well-targeted to the poorest children and to schools that serve very poor areas.

Más sobre este tema

Stimulus Keeping 6 Million Americans Out of Poverty in 2009, Estimates Show

End Notes

[1] “Estimated Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act on Employment and Economic Output as of September 2009,” Congressional Budget Office, November 2009, p. 1.

[2] “Preliminary Analysis of the President’s Budget and an Update of CBO’s Budget and Economic Outlook,” Congressional Budget Office, March 2009, p. 29.

[3] The seven provisions included in the analysis are: (1) new Making Work Pay tax credit; (2) expanded Child Tax Credit; (3) expanded Earned Income Tax Credit; (4) additional weeks of emergency unemployment compensation; (5) a $25 per week supplement for unemployed workers receiving unemployment benefits; (6) one-time payment of $250 to elderly and people with disability; and (7) increased Supplemental Nutrition Assistance program benefits. For additional information, see: Arloc Sherman, “Stimulus Keeping 6 Million Americans Out of Poverty in 2009, Estimates Show,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 9, 2009, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=2910.

[4] Total education funding through ARRA, including both fiscal relief and programmatic funding, was found to have created or saved 326,593 education jobs. US Department of Education, “American Recovery and Reinvestment Act Report: Summary of Programs and State-by-State Data,” November 2, 2009.

[5] Executive Office of the President, Council of Economic Advisers, “The Economic Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act 2009,” September 10, 2009.

[6] Cindy Redcross, MDRC, “Using NDNH Data to Evaluate Transitional Jobs,” presentation at the National Association for Welfare Research and Statistics annual conference, July 13, 2009.