- Home

- Income Security

- Tribal TANF

Policy Basics: Tribal TANF

The 1996 law that created the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program gave federally recognized Indian tribes the option to operate their own TANF programs. Over the last two decades, the number of Tribal TANF programs has more than doubled, from 36 in 2002 to 75 today. Nearly half of the 574 federally recognized tribes are now served by a Tribal TANF program, which enables them to better meet community needs, deliver services in ways that honor their culture, and take advantage of additional flexibilities.

Background

To align with federal TANF law, this report uses the terms “Indian tribe” and “Indian” to refer to federally recognized tribes (including Alaska Native Villages) and their citizens. These terms do not include state-recognized tribes, unrecognized tribes, or others that self-identify as American Indians or Alaska Natives but are not federally recognized tribes or citizens of those tribes.

Federally recognized tribes or consortia of tribes are eligible to operate Tribal TANF programs. (In Alaska, where the relationship between the federal government and Native peoples differs from the other states, the Metlakatla Indian Community and the 12 Alaska Native Regional Corporations may operate such programs.) Eligible tribes receive federal funding as a tribal block grant, technically called a Tribal Family Assistance Grant. Like states, tribes can use these funds for a broad range of activities related to promoting the four purposes of TANF specified in federal law: (1) assisting families in need so children can be cared for in their own homes or the homes of relatives; (2) reducing the dependency of parents in need by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage; (3) preventing pregnancies among unmarried persons; and (4) encouraging the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.

Tribes have used their TANF funds for cash assistance, child care, education and training programs, subsidized employment, transportation assistance, and other programs.

Whom Does Tribal TANF Serve?

Tribes have flexibility to define the borders of the area that their Tribal TANF program will serve. For example, the Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla Indians designated a service area for their Tribal TANF program to extend beyond their reservation in Riverside County, California to include all of Los Angeles and Riverside counties. The Oneida Nation of Wisconsin decided to keep the service area within their reservation, but they allow citizens of any federally recognized tribe living there to be eligible for their Tribal TANF program.

Tribes also have flexibility to establish criteria for who is eligible for Tribal TANF, including complete flexibility to set TANF income thresholds and other financial eligibility criteria, such as whether to limit the value of assets a family can have while participating in the program. In Alaska, however, Tribal TANF programs are required by federal law to have eligibility criteria comparable to those of Alaska’s state TANF program, though the state can waive this requirement at the request of tribes. Tribal TANF programs that receive state maintenance-of-effort (MOE) funds (the amount of state funding each state must spend annually to qualify for federal TANF funds) may also be required to align their eligibility criteria with that of the state TANF program.

Tribal TANF programs assisted just over 10,000 families per month on average in fiscal year 2018, the latest data available. For individual tribes, average monthly caseloads ranged from under ten families (in seven programs) to over 2,000 families (in the Navajo Nation’s program). The average caseload exceeds 100 families in 26 Tribal TANF programs and exceeds 500 families in five programs. Compared to families served by state TANF programs, families served by Tribal TANF are more likely to be headed by two parents and to have more than one child; they are less likely to be “child-only” cases, where only the child receives assistance.

How Is Tribal TANF Funded?

Each tribe operating a Tribal TANF program receives a fixed tribal block grant out of the overall federal TANF block grant, which has remained at $16.5 billion annually since 1997. Federal allocations to Tribal TANF programs totaled $209 million in fiscal year 2020, with individual tribal block grants ranging from $77,200 to $31.2 million; tribal block grants exceeded $1 million for 40 tribes and exceeded $10 million for three tribes. As with states, tribal block grants have not been adjusted for inflation and have lost 40 percent of their value since 1997; nor have they been adjusted for demographic shifts over time, which for some tribes have been significant.

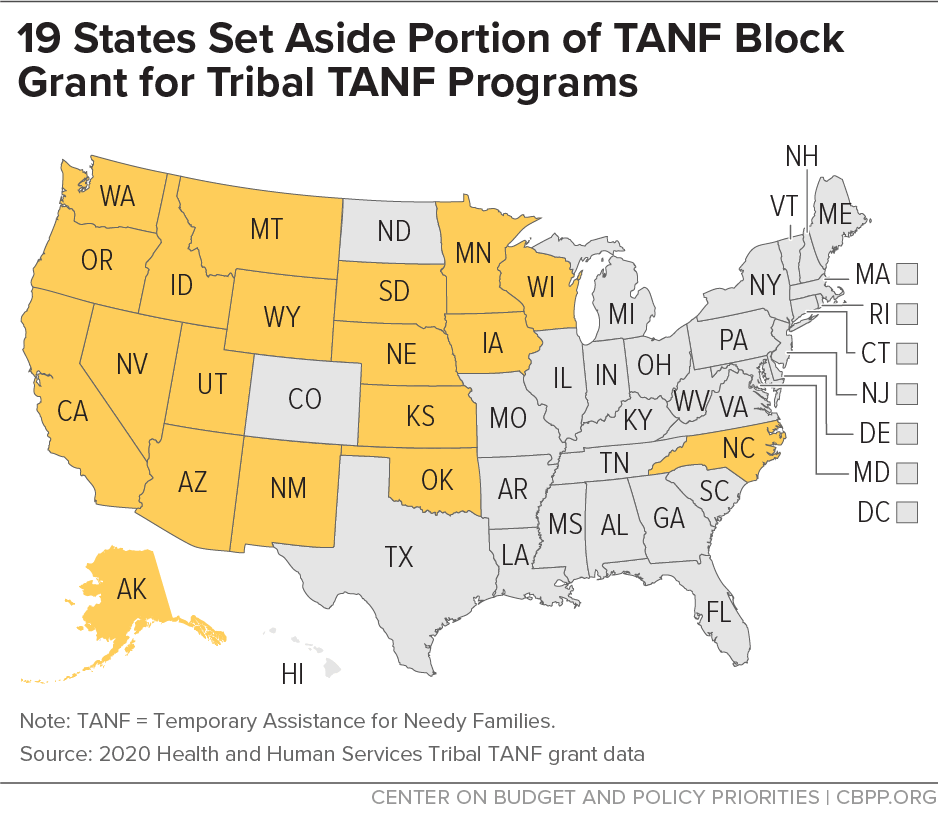

Tribes had no role in administering TANF’s predecessor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), and their citizens were served by state AFDC programs, where the federal government contributed at least $1 in matching funds for every dollar that states spent. Under the 1996 law that created TANF, a Tribal TANF program’s block grant is based on an estimate of federal funding in 1994 for state AFDC and related programs (excluding child care) that served Indian families in the service area designed in the tribe’s Tribal Family Assistance Plan. (The number of Indian families served is based on 1994 state AFDC caseload data.) The amount of the tribal block grant is then deducted from the state’s TANF block grant. Nineteen states have part of their block grant set aside for Tribal TANF. (See figure below.) In 2020, set-asides for Tribal TANF programs ranged from just under $70,000 for Nevada to $87 million for California.

State AFDC caseload data used in calculating the tribal block grant can underestimate the resource needs of Tribal TANF programs. For example, in 1998, the Klamath Tribes’ TANF caseload grew to nearly double the 1994 AFDC caseload used to determine their tribal block grant. Tribes can negotiate with the state to come up with a mutually acceptable set-aside for the tribal block grant. But once a tribe has negotiated its tribal block grant it cannot be renegotiated unless the tribe wishes to expand its designated service area.

States can provide state funds to Tribal TANF programs and count them toward their TANF MOE requirement. But states can cut back on or end MOE funding to Tribal TANF at any time, and lack of state MOE funds can seriously hinder the development of Tribal TANF programs. Tribes have no MOE requirement, but they must use their own funds for planning and program development. This can be a significant financial burden for tribes, whose financial resources are often quite limited.

Federal law caps the amount of tribal block grant funds that can be spent on program administration at 35 percent in the first year of a program, 30 percent in the second, and 25 percent for all subsequent years. (This exceeds the 15 percent limit for state programs.) Additionally, tribes cannot access the TANF Contingency Fund, which is meant to provide additional federal funds in times of increased economic hardship. However, Congress did provide tribes with access to temporary additional funds during recent downturns through the TANF Emergency Fund and the Pandemic Emergency Assistance Fund; these funds were a significant source of resources for tribes during challenging economic times.

The Indian Employment, Training and Related Services Demonstration Act of 1992 allows tribes to integrate employment, training, and related services programs — including Tribal TANF — into a single program, known as a 477 program, with a single budget that is overseen by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Twenty-two Tribal TANF programs are integrated into 477 programs.

What Flexibilities Are Available to Tribal TANF Programs?

Under the 1996 law, tribes have flexibilities when designing their TANF programs that states don’t have. (As noted above, federal law requires Tribal TANF programs in Alaska to set program requirements comparable to those in the state’s TANF program, unless the state waives that requirement.) Tribes can use these flexibilities to offer TANF services that better align with their culture and community needs. The flexibilities around work may be especially important to tribes. Studies show that Tribal TANF recipients’ goals are harder to achieve because they face significant barriers to employment, including health issues, lack of child care and transportation, and long distances to available jobs.

Key flexibilities available to tribes include:

Work participation rate (WPR): A TANF program’s WPR measures the share of work-eligible recipients that participate in work activities. States must meet a WPR of 50 percent for all families and 90 percent for two-parent families (though states can receive credit to lower that target by reducing their caseloads or spending more than their required amount of MOE). In contrast, tribes negotiate their work rate with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS); rates range from 20 to 58 percent of all work-eligible families, with the average being 34 percent. Also, unlike states, tribes do not have a separate, higher two-parent work rate. On the other hand, tribes are not eligible for the caseload reduction credit, which has allowed many states to reduce their work rates to zero. Nevertheless, virtually all Tribal TANF programs met their work rates in 2019, the latest year available.

Work requirements: Tribes can negotiate with HHS to count additional work activities beyond the 12 specified in federal law toward their work rate. Such additional activities have included culturally relevant work activities and subsistence activities like farming, hunting, and fishing. For example, the Navajo Nation’s Tribal TANF program has added agricultural subsistence and traditional support and mentoring to its work activities so that Tribal TANF aligns with the tribe’s public health goals.

In 2018 (the latest year available), most adult Tribal TANF recipients participated in work activities and of those who did, 4 in 10 participated in “other” work activities established by tribes. As with states, federal rules limit the duration of job search and job readiness activities for each participant that they can count toward their WPR. But unlike states, tribes are not required to limit the amount of time a recipient participates in vocational education and training.

In addition to allowable activities, tribes can negotiate the required number of hours that work-eligible recipients must complete; this ranges from 16 to 48 hours per week. Some Tribal TANF programs require a higher number of hours for two-parent families.

Like states, tribes are required to reduce or take away benefits (known as a “sanction”) when a family member “refuses” to comply with work requirements as defined by the tribe without “good cause.” Tribes have flexibility to set their own sanction policies, including the amount and duration of sanctions, as well as how to define good cause.

Time limits: Tribes must specify a time limit on TANF assistance to families with an adult recipient but can negotiate its length with HHS. Unlike states, tribes are not subject to the 60-month federal time limit. Tribes can also apply different time limits to different parts of their designated service area, such as for areas with higher and lower employment opportunities. They can also exempt families from the time limit for reasons of domestic violence or hardship (as defined by the tribe) and may negotiate a cap on the number of families who can be given a “hardship exemption” that is higher than the 20 percent specified in federal law.

Eligibility requirements: Unless specifically mentioned in federal law, tribes do not have to adopt the few federal restrictions on TANF eligibility that apply to states. For example, tribes are not required to condition TANF benefits on the assignment of child support rights and cooperation with child support enforcement. Nor must they abide by the federal ban on providing TANF assistance to people with drug-related felony convictions.

| TABLE 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Summary of Key Differences Between Tribal and State TANF Programs | ||

| Tribal TANF | State TANF | |

| Maintenance-of-effort (MOE) spending requirement | No; but tribes must use their own funds for planning and development | Yes |

| Access to state MOE funds | States can, but are not required to, provide tribes with MOE funds | Yes |

| Access to TANF Contingency Fund | No | Yes |

| Work participation rate (WPR) | Tribes can negotiate their WPR and need not set a separate, higher rate for two-parent families | States must meet a 50 percent WPR for all families and a 90 percent WPR for two-parent families |

| Access to caseload reduction credit to lower WPR | No | Yes |

| Time limits on families with an adult who can receive assistance using federal TANF funds | Tribes can negotiate their time limit | States can use federal funds to provide assistance for up to 60 months for all families, and for an unlimited number of months for families granted a hardship exemption (see below). |

| Percent of families who can receive a “hardship exception” to the time limit | Tribes can negotiate a higher share than 20 percent | 20 percent; states cannot negotiate |

| Work activities countable to WPR | Tribes can negotiate to add activities beyond the 12 in federal law, such as culturally relevant and subsistence activities | States can only count the 12 activities in federal law |

| Limit on vocational education | No | Yes, 12-month lifetime limit |

| Must condition TANF benefits on assigning child support rights and cooperating with child support enforcement | No | Yes |

| May provide benefits to people with drug-related felony convictions | Yes; tribes are not subject to the federal ban | Federal ban applies to states (but they can pass legislation to opt out) |

| TABLE 2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tribal TANF Funding, Caseload, and Work Programs Data | |||||||||||

| Tribe/tribal consortia | Tribal Block Grant, 2020 (in millions) | State(s) Setting Aside Federal TANF Funds for Tribe | Average Monthly Caseload, 2018 | Work Participation Rate, 2019 | Work Hours Required – 1 Parent, 2019 | Work Hours Required – 2 Parents, 2019 | |||||

| Association of Village Council Presidents | $5.42 | AK | 594 | 32.0 | 25 | 25 | |||||

| Bad River Band of Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa | $0.29 | WI | 3 | 35.0 | 30 | 35 | |||||

| Blackfeet Nation | $3.09 e | MT | 277 | 33.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Bristol Bay Native Association | $1.22e | AK | 94 | 35.0 | 25 | 25 | |||||

| Central Council Tlingit & Haida Indians | $2.37 e | AK | 232 | 30.0 | 20 | 40 | |||||

| Cherokee Nationa | $5.98 | OK | N/a | N/a | N/a | N/a | |||||

| Chippewa-Cree Indians of the Rocky Boy’s Reservation | $1.26 | MT | 97 | 30.0 | 30 | 30 | |||||

| Coeur D'Alene Tribeb | $0.16 | ID | 38 | N/a | N/a | N/a | |||||

| Confederated Salish & Kootenai of the Flathead Reservation | $2.14e | MT | 120 | 58.0 | 32 | 32 | |||||

| Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation | $3.40 | WA | 221 | 36.0 | 20 | 20 | |||||

| Confederated Tribes of the Siletz Reservation | $0.66 e | OR | 25 | 35.0 | 26 | 26 | |||||

| Cook Inlet Tribal Council | $6.08 e | AK | 559 | 35.0 | 30 | 30 | |||||

| Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians | $0.80 | NC | 40 | 30.0 | 28 | 28 | |||||

| Eastern Shoshone Tribes of the Wind River Reservation | $1.64 e | WY | 115 | 29.0 | 20 | 20 | |||||

| Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria | $1.64 | CA | 72 | 35.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Forest County Potawatomi Communityb | $0.12 | WI | 2 | N/a | N/a | N/a | |||||

| Fort Belknap Community Council | $1.01 e | MT | 186 | 39.0 | 20 | 40 | |||||

| Hoopa Valley Tribe | $1.21 | CA | 39 | 40.0 | 32 | 37 | |||||

| Hopi Tribe | $0.72 | AZ | 58 | 31.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Karuk Tribe | $1.21 | CA | 39 | 40.0 | 20 | 20 | |||||

| Klamath Tribes | $0.46 | OR | 41 | 40.0 | 20 | 20 | |||||

| Kodiak Area Native Association | $0.42 e | AK | 25 | 35.0 | 20 | 20 | |||||

| Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians | $0.64 | WI | 38 | 25.2 | 16 | 24 | |||||

| Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians | $0.61 | WI | 16 | 42.0 | 24 | 36 | |||||

| Lower Elwha Tribe | $0.50 | WA | 59 | 42.0 | 20 | 40 | |||||

| Lummi Nation | $1.51 e | WA | 178 | 28.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Maniilaq Association | $1.06 e | AK | 74 | 26.0 | 18 | 18 | |||||

| Menominee Indian Tribe | $1.27 | WI | 17 | 25.0 | 20 | 40 | |||||

| Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe | $4.55 e | MN | 42 | 35.0 | 20 | 20 | |||||

| Morongo Band of Mission Indians | $5.61 | CA | 92 | 33.0 | 24 | 24 | |||||

| Muscogee (Creek) Nation | $3.11 | OK | 132 | 35.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Navajo Nation | $31.17 | AZ, NM, UT | 2,045 | 32.0 | 24 | 48 | |||||

| Nez Perce Tribe | $0.50 | ID | 27 | 35.0 | 20 | 20 | |||||

| Nooksack Indian Tribe | $0.91 | WA | 34 | 50.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| North Fork Rancheria | $2.15 | CA | 55 | 33.0 | 24 | 32 | |||||

| Northern Arapaho Tribe of the Wind River Indian Reservation | $1.64 e | WY | 123 | 34.0 | 25 | 30 | |||||

| Omaha Tribe | $0.68 | IA, NE | 111 | 26.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Oneida Nation of Wisconsin | $0.84 | WI | 10 | 35.0 | 32 | 32 | |||||

| Osage Nation | $0.42 e | OK | 3 | 40.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Owens Valley Career Development Center | $15.29 | CA | 556 | 36.0 | 28 | 32 | |||||

| Pascua Yaqui Tribe | $1.73 | AZ | 114 | 36.0 | 30 | 30 | |||||

| Pechanga Band of Luiseno Mission Indians | $0.91 | CA | 3 | 35.0 | 24 | 34 | |||||

| Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe | $0.52 e | WA | 11 | 25.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Prairie Band Potawatomi Nationc | $0.12 | KS | N/a | 27.0 | 25 | 40 | |||||

| Pueblo of Zuni | $0.80 e | NM | 83 | 35.0 | 26 | 26 | |||||

| Quileute Indian Tribe | $0.75 | WA | 37 | 42.0 | 25 | 40 | |||||

| Quinault Indian Nation | $1.70 | WA | 92 | 28.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians | $0.31 | WI | 17 | 35.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indiansc | $2.98 | MN | N/a | 24.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Robinson Rancheria | $7.73 | CA | 496 | 38.0 | 22 | 22 | |||||

| Round Valley Indian Tribe | $1.14 | CA | 90 | 29.0 | 20 | 20 | |||||

| Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community | $0.71 | AZ | 39 | 29.0 | 20 | 35 | |||||

| San Carlos Apache Tribe | $1.97 | AZ | 94 | 20.0 | 25 | 25 | |||||

| Santee Sioux Nation | $0.14 | NE | 44 | 35.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Santo Domingo Tribec | $0.24 | NM | N/a | 22.0 | 22 | 22 | |||||

| Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians | $2.22 | CA | 67 | 30.0 | 28 | 32 | |||||

| Shingle Springs Band of Milwok Indians | $4.99 | CA | 189 | 38.0 | 23 | 32 | |||||

| Shoshone-Bannock Tribes of the Fort Hall Reservation | $0.86 e | ID | 125 | 46.0 | 20 | 20 | |||||

| Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate of the Lake Traverse Reservationd | $0.61 e | SD | 108 | 35.0 | 25 | N/a | |||||

| Soboba Band of Luiseno Indians | $1.72 | CA | 45 | 36.0 | 20 | 20 | |||||

| Sokaogon Chippewa Community of the Mole Lake Band of Chippewa Indians | $0.08 | WI | 2 | 40.0 | 32 | 40 | |||||

| Southern California Tribal Chairmen’s Association | $9.91 | CA | 149 | 43.0 | 30 | 40 | |||||

| South Puget Inter-Tribal Planning Agency (SPIPA) | $5.22 | WA | 239 | 32.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Spokane Tribe | $8.4e | WA | 193 | 34.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Stockbridge-Munsee Community of Mohican Indians | $0.14 | WI | 3 | 37.0 | 24 | 36 | |||||

| Tanana Chiefs Conference | $2.44 e | AK | 174 | 35.0 | 30 | 30 | |||||

| Tolowa Dee-Ni’ Nationc | $0.56 | CA, OR | N/a | 20.0 | 24 | 34 | |||||

| Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla Indians | $18.91 | CA | 615 | 33.0 | 30 | 40 | |||||

| Tulalip Tribes | $0.98e | WA | 179 | 39.0 | 20 | 40 | |||||

| Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indiansc | $1.77 | CA | N/a | 26.0 | 18 | 24 | |||||

| Upper Skagit Indian Tribe | $0.12 | WA | 11 | 25.0 | 16 | 16 | |||||

| Washoe Tribe | $9.42 | CA, NV | 308 | 43.0 | 24 | 30 | |||||

| White Mountain Apache Tribe | $1.91 | AZ | 81 | 30.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Winnebago Tribe | $0.92e | IA, NE | 87 | 35.0 | 20 | 30 | |||||

| Yurok Tribe | $1.27 | CA | 57 | 38.0 | 21 | 30 | |||||

a The Cherokee Nation’s Tribal TANF program was established in 2019; therefore, program data are not reflected in columns showing caseload data or WPR data.

b Data not included in HHS 2019 Tribal work participation rate data because they have no work-eligible adults on their caseload.

c Data not included in HHS 2018 Tribal caseload data.

d The Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate’s Tribal TANF program only has required work hours for single parents.

e Tribe receives Tribal TANF funding through a 477 program.

Source: CBPP analysis of HHS data