Entering Their Second Decade, Affordable Care Act Coverage Expansions Have Helped Millions, Provide the Basis for Further Progress

End Notes

[1] Several states and jurisdictions began implementing full or partial Medicaid expansion prior to January 1, 2014: California (July 2011), Connecticut (April 2010), the District of Columbia (July 2010), Minnesota (March 2011), New Jersey (April 2011), and Washington (January 2011).

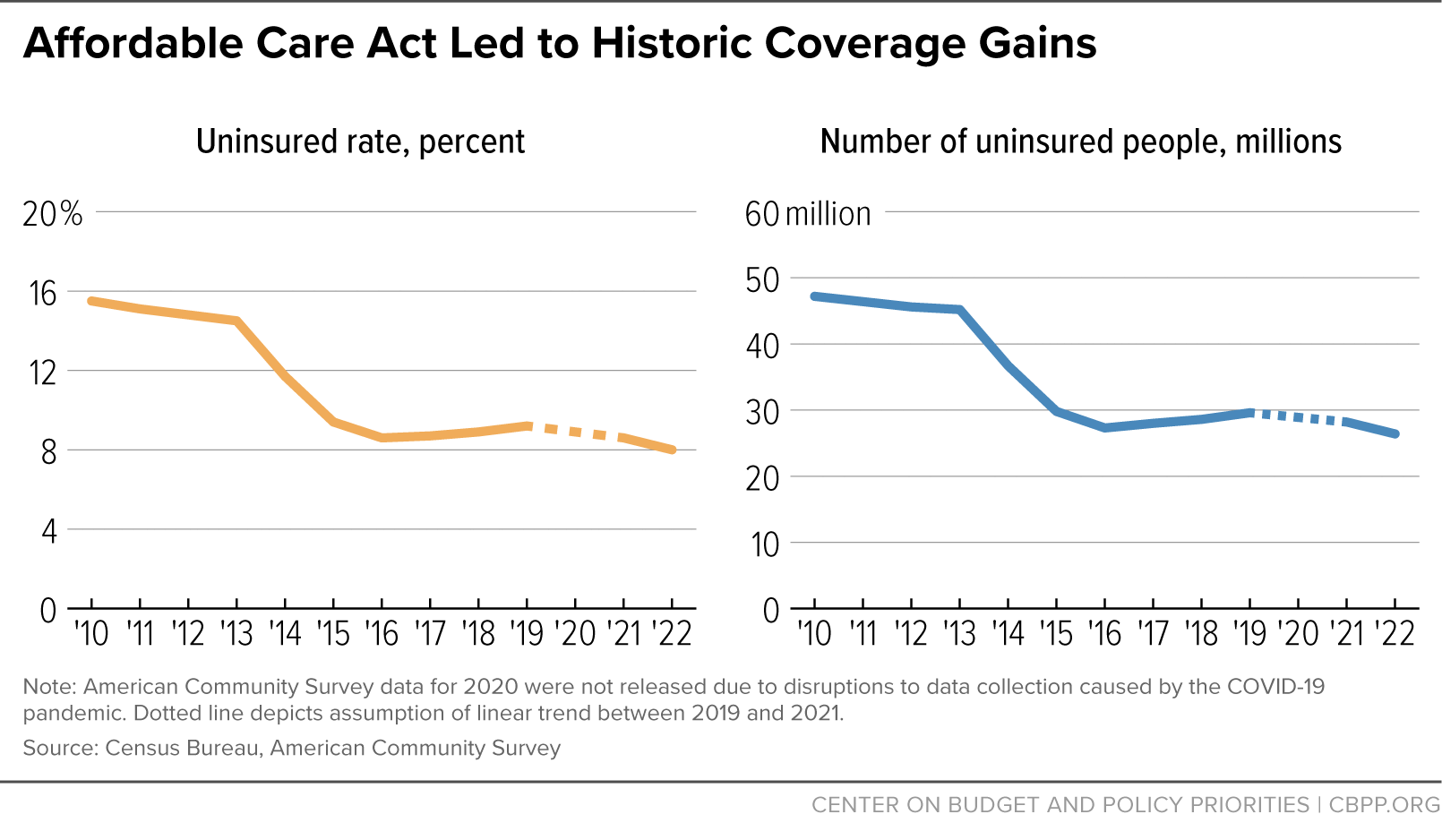

[2] Census Bureau, 2013 and 2022 American Community Survey.

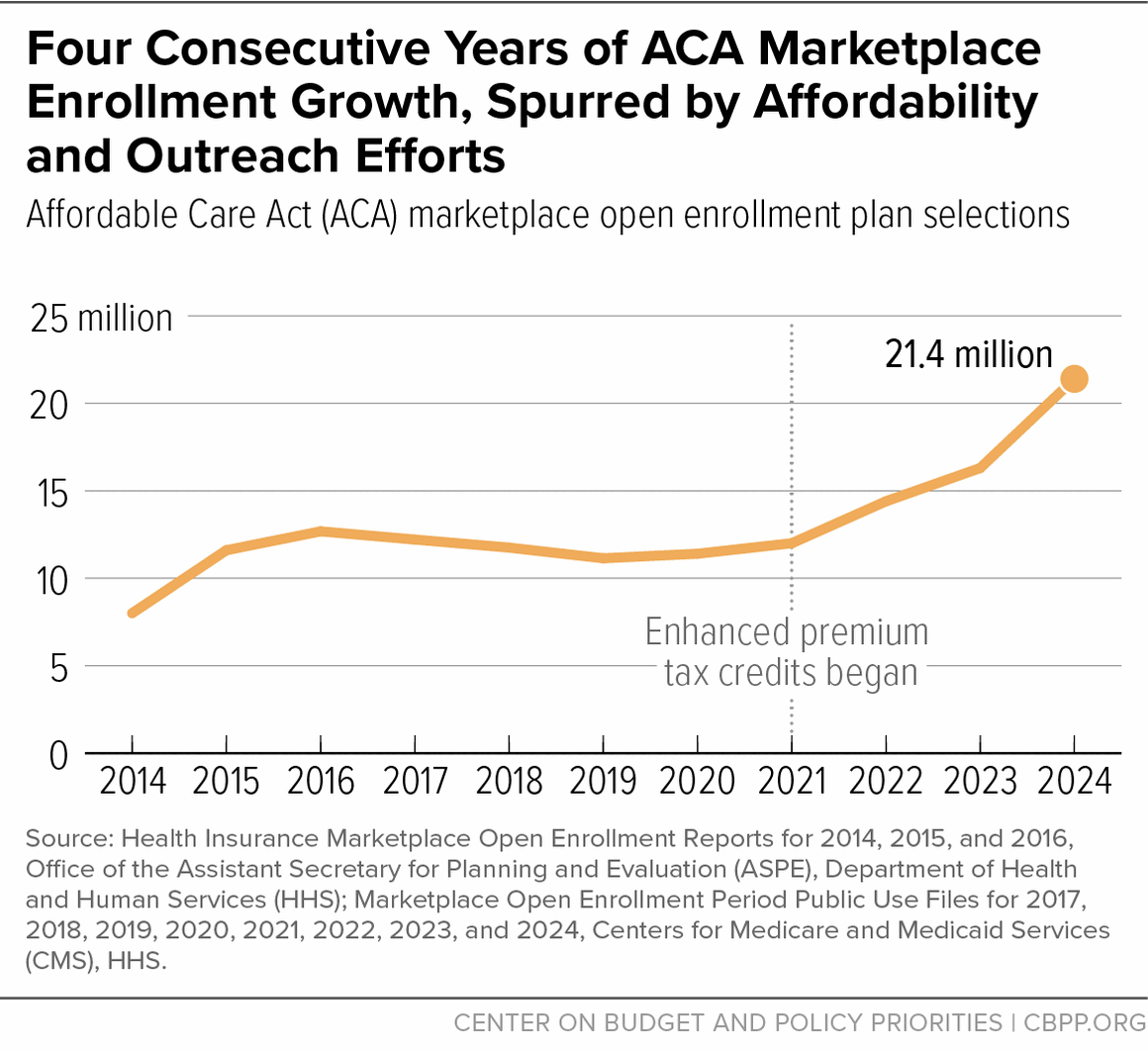

[3] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Medicaid Enrollment Data Collected Through MBES, January 2024, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/national-medicaid-chip-program-information/medicaid-chip-enrollment-data/medicaid-enrollment-data-collected-through-mbes/index.html; CMS, “Historic 21.3 Million People Choose ACA Marketplace Coverage,” January 24, 2024, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/historic-213-million-people-choose-aca-marketplace-coverage.

[4] CBPP analysis of 2013 and 2022 American Community Survey data. The American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) category includes people who may be AIAN alone or in combination with other races and ethnicities. The Latino category includes people of any race. The Black and white categories include only people who identify as a single race and not Latino.

[5] CMS, “Biden-Harris Administration Launches Window-Shopping Ahead of 11th ACA Marketplace Open Enrollment Period,” October 25, 2023, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/biden-harris-administration-launches-window-shopping-ahead-11th-aca-marketplace-open-enrollment.

[6] CMS, “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2024 Open Enrollment Report,” March 22, 2024, https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-reports/marketplace-products/2024-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files.

[7] CMS, “Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2023 Snapshot and Full Year 2022 Average,” September 2023, https://www.cms.gov/files/document/early-2023-and-full-year-2022-effectuated-enrollment-report.pdf.

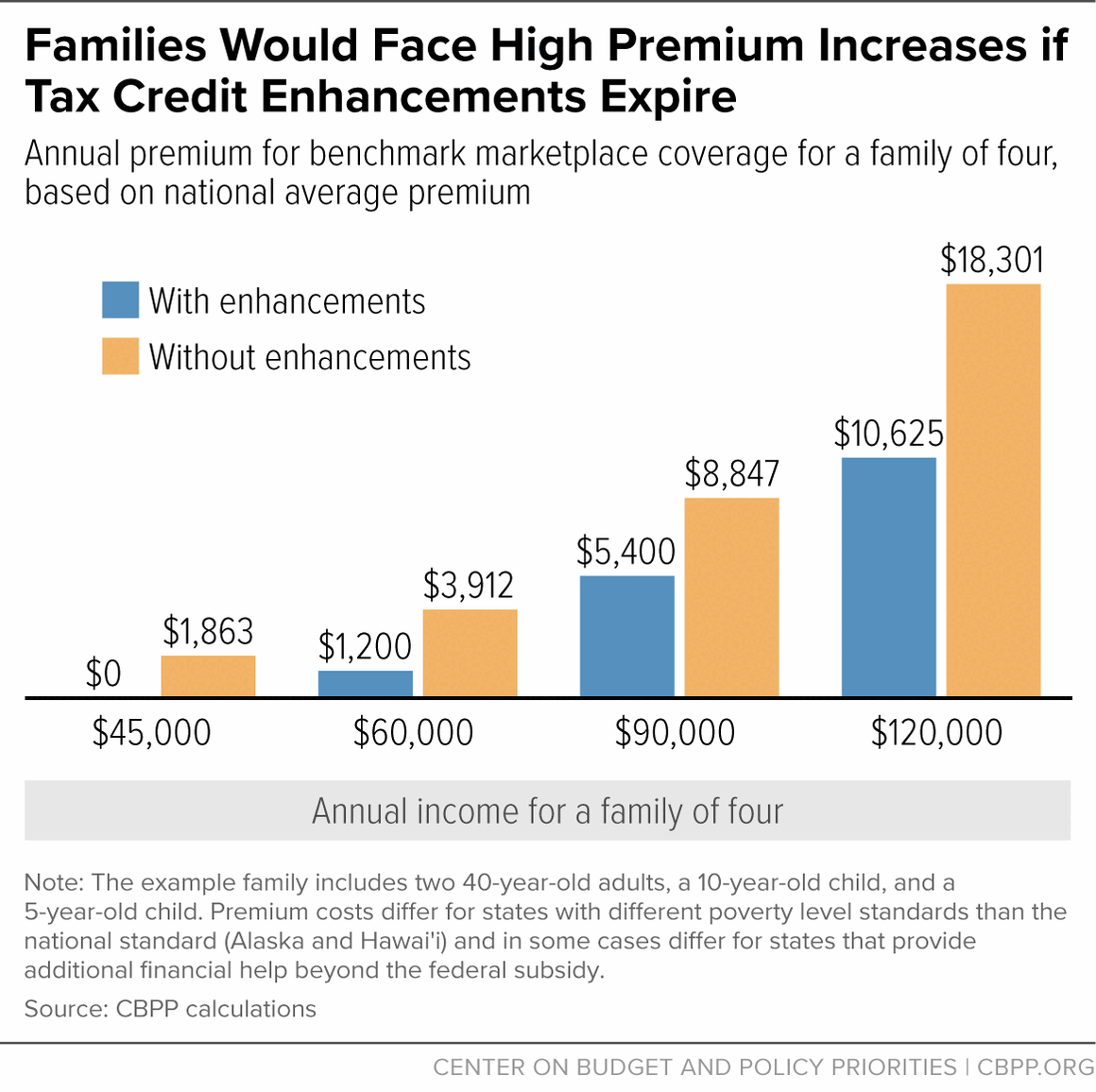

[8] The marketplace uses the poverty guidelines, commonly known as the federal poverty level (FPL), in effect at the start of the open enrollment period to determine premium tax credits for the subsequent plan year. All marketplace examples and premium calculations in this report are for the 2024 plan year and therefore use the 2023 FPL. In contrast, Medicaid uses the FPL in effect when a person enrolls. Examples of income levels for Medicaid eligibility therefore use the 2024 FPL.

[9] Before the American Rescue Plan was enacted, people with incomes greater than 400 percent of the FPL were not eligible for PTCs. By setting the upper required contribution percentage at 8.5 percent of income, the Rescue Plan makes some people with incomes greater than 400 percent of the FPL newly eligible for PTCs (if their premiums would exceed 8.5 percent of income). The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) estimates that in 2023, 1.4 million individuals with incomes greater than 400 percent of the FPL received PTCs because of this provision. CMS, “Biden-Harris Administration Celebrates the Affordable Care Act’s 13th Anniversary and Highlights Record-Breaking Coverage,” March 23, 2023, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/biden-harris-administration-celebrates-affordable-care-acts-13th-anniversary-and-highlights-record.

[10] Deductibles within each plan level did not decrease between 2021 and 2023, but the median individual deductible among plan selections did, suggesting that people selected higher-value plans in 2023. CMS, “2014-2023 OEP Plan Design Public Use File,” September 6, 2023, https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/marketplace-products/2023-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files.

[11] Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) renewals and terminations resumed in 2023 after being paused since 2020 to keep people covered during the COVID-19 pandemic. As of February 13, 2024, an estimated 16.9 million people have lost Medicaid or CHIP coverage. See: https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-enrollment-and-unwinding-tracker-overview/. Many of these individuals remain eligible for Medicaid or CHIP, but some are now eligible for marketplace coverage. As of December 31, 2023, 2.4 million marketplace plan selections for 2024 were made by people who were previously enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP. See: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/historic-213-million-people-choose-aca-marketplace-coverage.

[12] Anupama Warrier et al., “HealthCare.gov Enrollment by Race and Ethnicity, 2015-2023,” Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, HHS, March 22, 2024, https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/marketplace-enrollment-race-ethnicity-2015-2023.

[13] CMS, “Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files,” September 6, 2023, https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/marketplace-products/2023-marketplace-open-enrollment-period-public-use-files. Note that because the 2021 Marketplace Public Use File does not include marketplace enrollment data by income for Idaho, Idaho is excluded from this calculation.

[14] The ACA was supposed to provide Medicaid coverage to all adults with low incomes, but in its NFIB v. Sebelius decision of 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states would have the option to expand their Medicaid programs rather than face a federal requirement to do so. Because the ACA presumed that all people under 138 percent of the poverty level would be covered by Medicaid and thus made people under the poverty level ineligible for PTCs, the court’s decision led to a “coverage gap” for people with incomes under the poverty level in states that opted not to expand Medicaid. As discussed below, such individuals are ineligible for both Medicaid expansion and marketplace PTCs.

[15] CMS, Medicaid Enrollment Data Collected Through MBES, January 2024, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/national-medicaid-chip-program-information/medicaid-chip-enrollment-data/medicaid-enrollment-data-collected-through-mbes/index.html. These numbers are likely to drop as states continue “unwinding” pandemic-era continuous coverage protections.

[16] Madeline Guth, Rachel Garfield, and Robin Rudowitz, “The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Studies from January 2014 to January 2020,” KFF, March 17, 2020, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review/.

[17]Laura Harker and Breanna Sharer, “Medicaid Expansion: Frequently Asked Questions,” CBPP, forthcoming. See also, Madeline Guth and Maghana Ammula, “Building on the Evidence Base: Studies on the Effects of Medicaid Expansion, February 2020 to March 2021,” KFF, May 6, 2021, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/building-on-the-evidence-base-studies-on-the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-february-2020-to-march-2021/; Madeline Guth, Rachel Garfield, and Robin Rudowitz, op. cit.

[18] Matthew Buettgens and Urmi Ramchandani, “3.7 Million People Would Gain Health Coverage in 2023 if the Remaining 12 States Were to Expand Medicaid Eligibility,” Urban Institute, August 3, 2022, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/3.7%20Million%20People%20Would%20Gain%20Health%20Coverage%20If%20the%20Remaining%20States%20Were%20to%20Expand%20Medicaid.pdf; Matthew Buettgens, “Medicaid Expansion Would Have a Larger Impact Than Ever during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Urban Institute, January 2021, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103536/medicaid-expansion-would-have-a-larger-impact-than-ever-during-the-covid-19-pandemic_1.pdf.

[19] Gideon Lukens, “Record Low Uninsured Rate Offers Roadmap to Long-Term Coverage Gains,” CBPP, September 14, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/record-low-uninsured-rate-offers-roadmap-to-long-term-coverage-gains.

[20] CBPP calculations using 2024 benchmark (second-lowest-cost silver tier plan) premiums with age adjustments. Examples are not projections but rather illustrate the magnitude of the shift in costs that typical individuals and families under these scenarios would experience if the PTC enhancements expire. Actual costs will be determined by future premiums, contribution percentages, and other unknown factors. These national estimates are applicable in all states except for a small number that have state-specific poverty levels and/or provide additional premium subsidies. The family of four includes two 40-year-old parents, a 10-year-old, and a 5-year-old. See Appendix Table 2 for state-specific estimates.

[21] Matthew Buettgens, Jessica Banthin, and Andrew Green, “What If the American Rescue Plan Act Premium Tax Credits Expire? Coverage and Cost Projections for 2023,” Urban Institute, April 7, 2022, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/what-if-american-rescue-plan-act-premium-tax-credits-expire.

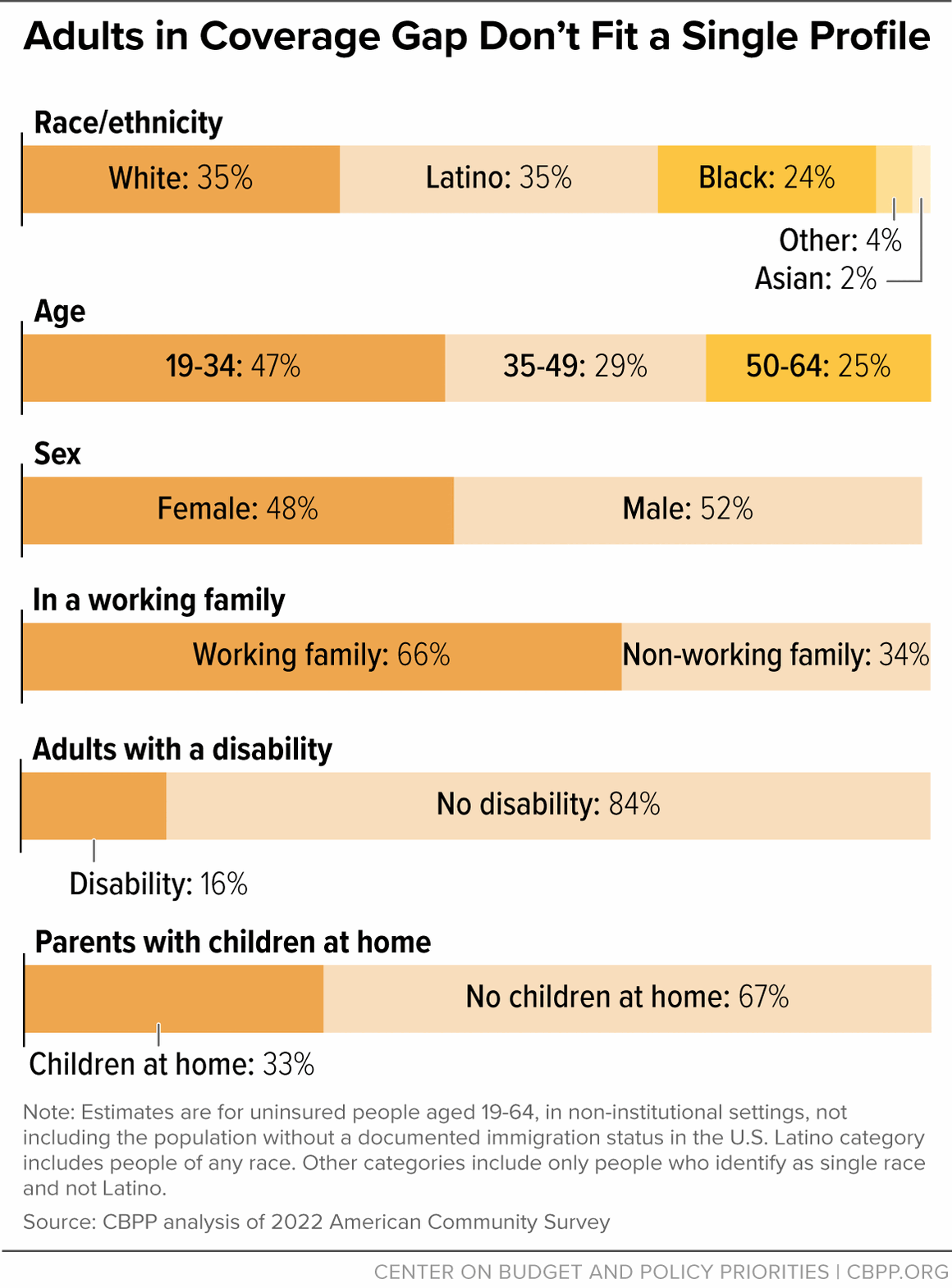

[22] CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey. The coverage gap was created when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in NFIB v. Sebelius that the ACA’s Medicaid expansion was an option for states. While PTCs are available to individuals over 100 percent of the poverty level, the law does not authorize PTCs for people with incomes under 100 percent, making marketplace coverage unaffordable for people with low incomes.

[23] KFF, “State Health Facts: Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults as a Percent of the Federal Poverty Level,” January 1, 2023, https://www.kff.org/affordable-care-act/state-indicator/medicaid-income-eligibility-limits-for-adults-as-a-percent-of-the-federal-poverty-level/?currentTimeframe=0&selectedRows=%7B%22states%22:%7B%22alabama%22:%7B%7D,%22florida%22:%7B%7D,%22georgia%22:%7B%7D,%22kansas%22:%7B%7D,%22mississippi%22:%7B%7D,%22south-carolina%22:%7B%7D,%22tennessee%22:%7B%7D,%22texas%22:%7B%7D,%22wisconsin%22:%7B%7D,%22wyoming%22:%7B%7D%7D%7D&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Parents%20(in%20a%20family%20of%20three)%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D. Medicaid eligibility thresholds as of January 2023; dollar amounts shown here reflect 2024 poverty guidelines determined by HHS.

[24] CBPP analysis of 2022 American Community Survey.

[25] The White House, “President’s Budget,” March 2024, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/.