Thank you for the opportunity to testify. I am Will Fischer, a Senior Policy Analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The Center is an independent, non-profit policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income families. The Center's housing work focuses on improving the effectiveness of federal low-income housing programs.

The Section 8 Savings Act (SESA) discussion draft dated October 5 contains important improvements to the Section 8 housing voucher program and other federal rental assistance programs that were also contained in a draft of the bill released in June 2011. These well-crafted measures would ease administrative burdens, make it easier for private owners to participate in the voucher program, establish voucher funding rules that would help local housing agencies use funds efficiently, and generate more than $700 million in federal savings. SESA's core provisions are urgently needed at a time when budgets are tight and housing needs are high, and it will be important that Congress move promptly to enact them. [1]

This testimony focuses on several provisions of SESA that are designed to support self-sufficiency and on the Moving to Work Improvement, Expansion, and Permanency Act (MTWIEPA). SESA's self-sufficiency provisions should be improved in important ways, but they provide a promising framework. MTWIEPA, on the other hand, is not well-designed to help families become self-sufficient and would likely lead to many fewer families receiving housing assistance and have other harmful effects unrelated to self-sufficiency.

SESA's self-sufficiency provisions, like the bill as a whole, would make targeted changes to federal rental assistance programs while leaving in place the basic structure that has made the programs effective. SESA would support self-sufficiency in a number of ways, but this testimony will focus on four major provisions that would establish a Self-Sufficiency and Rental Assistance Counseling Support Program (SSRACSP), authorize a Rent Policy Demonstration, expand the Family Self-Sufficiency (FSS) program, and permit higher minimum rents.

Self-Sufficiency and Rental Assistance Counseling Support Program

Under SSRACSP, agencies that apply to participate and are selected by HUD would establish plans to provide services to help families move toward self-sufficiency. Participating agencies would be encouraged to form partnerships with local service providers and required to establish and monitor their compliance with benchmarks for supporting self-sufficiency.

This approach is generally sound. The emphasis on partnerships with local employment agencies and service providers is important. These entities will usually be better positioned to help families become employed or increase their earnings than housing agencies, which are primarily focused on providing housing assistance and assist many people who are unable to work because they are elderly or have disabilities. (Fifty percent of households living in public housing or receiving voucher assistance are elderly or disabled by HUD's definition, which means that the head of the household or spouse of the head is elderly or has a disability.) It would be far better to use existing workforce development resources to help families become self-sufficient than to push housing agencies to establish a parallel workforce development bureaucracy or divert scarce housing assistance resources to fund services.

In addition, it is appropriate that helping working families increase their earnings is a goal of the new initiative, along with preparing non-working families for work.[2] Despite the recent economic downturn, a large majority of work-able housing assistance recipients are strongly attached to the labor market. A preliminary CBPP analysis of HUD data finds that, among non-elderly, non-disabled households receiving voucher assistance in 2010, 65 percent worked in 2010 or were unemployed but had recently worked. The share employed is higher among households that receive housing assistance longer, but these households on average still have incomes far below the level needed to make housing affordable without subsidies.

Three key improvements are needed, however, to make the self-sufficiency program effective.

One important change would be to alter the incentive used to encourage agencies to apply for the program. The discussion draft stipulates that only participating agencies would be permitted to implement SESA's improvements to rules governing tenant rent determinations and voucher housing quality inspections. Those improvements would reduce burdens on housing agencies, private owners, and low-income families considerably, for example by reducing the frequency of inspections and of income determinations for fixed-income families.

Allowing only participating agencies to make use of these important improvements may encourage some agencies to apply, but for three reasons it is highly problematic. First, most agencies will need the administrative savings from SESA's rent and inspection provisions simply to make ends meet. Congress cut voucher administrative funding sharply in 2011, and the 2012 appropriations bills now under consideration would deepen this cut and also inadequately fund public housing operating subsides. Agencies should not be required to participate in a new self-sufficiency program that will require additional staff time in order to have access to the streamlining SESA provides.

Second, limiting applicability of the inspection and rent streamlining provisions would create a complex, largely arbitrary system in which one set of rules applies to families assisted by certain housing agencies and a second applies to families assisted by other agencies. For example, income reviews would be more burdensome and frequent for low-income tenants — and especially the elderly and people with disabilities — whose housing agencies opt not to (or are unable to) participate in SSRACSP. Similarly, the SESA inspection improvements that make it easier for private owners to rent to voucher holders would not be available to owners in the jurisdictions of non-participating agencies. This dual system would be confusing for low-income families and owners, and would complicate HUD's efforts to monitor and enforce compliance with federal rules.

Third, the October 5 SESA draft appears to exclude private owners of properties assisted through the project-based Section 8 program from the bill's rent provisions, since these provisions would apply only to "public housing agencies" that opt to participate in SSRACSP. [3] These agencies administer public housing and Section 8 vouchers, but project-based Section 8 building owners receive subsidies directly from HUD and make rent determinations themselves for the 1.2 million families they assist. It is not clear whether this limitation was intended. But if the rent provisions do not apply to project-based Section 8 owners, the bill would deny those owners substantial administrative savings and the rent provisions' overall impact would be reduced.

SEVRA's rent and inspection improvements should apply to all public housing agencies and private owners. Congress could instead provide an incentive for agencies to participate in SESA's new self-sufficiency program by directing HUD to award points for participation under the existing performance measurement systems, the Section 8 Management Assessment Program and Public Housing Assessment System.

In addition, the one-sided obligation SESA would place on housing agencies to engage in partnerships with providers of employment services would likely have only a limited impact, since these providers will often be unwilling to engage in meaningful partnerships with housing agencies. Forming partnerships may be especially difficult for smaller agencies, which have less ability to free up staff time for such efforts and may have difficulty persuading workforce development agencies to enter into special arrangements to serve a small number of housing assistance recipients. Three out of four housing agencies assist 550 or fewer households under the voucher and public housing programs, and since more than half of assisted households are elderly or disabled the number of candidates for employment services at these agencies typically will be much lower than the total number of families assisted.

SSRACSP would also be more effective if the Financial Services Committee worked with other committees to direct agencies receiving funding under Workforce Investment Act or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) programs to coordinate with housing agencies in identifying and delivering needed services to housing assistance recipients. In the case of the Workforce Investment Act, this approach could be supplemented by changing performance standards to encourage One-Stop Centers and training vendors who work through One-Stops to recruit and serve individuals who have relatively high barriers to work (as many housing assistance recipients do). Finally, some resources for Department of Labor and Department of Health and Human Services direct grant programs could be targeted on recipients of housing assistance.

There is a strong case to be made for targeting employment and supportive services in this manner, since the stability and other benefits provided by housing assistance could support the delivery of services. Evaluations of some welfare-to-work programs, for example, found that the programs had larger effects on housing assistance recipients than other families.[4] Moreover, increases in earnings among housing assistance recipients have the added benefit of reducing federal costs for housing assistance.

Use of Operating Subsidies and Administrative Fees for Self-Sufficiency Services

For a new self-sufficiency initiative to function effectively, it will be important that Congress provide full funding for the public housing operating fund and voucher administrative fees.[5] Congress could also clarify that these funds can be used for self-sufficiency services, although this appears to be permissible under current law.

SESA would also authorize HUD to conduct a limited demonstration of alternative rent policies. A targeted rent policy demonstration of this type would be the best way to test new rent policies and could potentially lead to significant improvements.

Today's rent rules generally work well, providing sufficient help to enable the neediest families to afford housing while not giving higher-income families more subsidy than they need. In addition, the current system maintains largely identical rules across programs and localities, making it easier for voucher holders to move from one community to another (for example to pursue a job opportunity), easier for private-sector owners and investors to participate in multiple programs and operate in multiple jurisdictions, and easier for HUD to provide effective oversight.

Most major changes — and particularly those that would result in sharply higher or lower subsidies for certain families — would carry substantial risks and tradeoffs. It is possible, however, that some substantial changes would have significant benefits that would justify enacting them at the federal level. For example, a policy of disregarding some percentage of earned income would carry added costs, but might encourage sufficient increases in earnings to offset a sizable share of the costs and justify the change. A demonstration could offer an opportunity to rigorously test policy alternatives to determine their costs and benefits relative to the current rules.

The limited SESA rent demonstration is strongly preferable to the alternative of allowing a large number of agencies to implement untested alternative rent policies. That approach could make housing assistance less efficient by fostering a complex patchwork of local rules. This would make it more difficult for HUD to provide adequate oversight, for private owners and lenders to navigate federal programs, and for families to use vouchers to move from one community to another (for example, to be closer to a job opportunity).

However, the SESA rent demonstration can and should be strengthened. A proposal included in HUD's 2012 budget for a similar demonstration would provide HUD broader flexibility to identify promising policies and would limit the demonstration to five years to avoid allowing policies that do not prove effective to remain in place indefinitely. Both of these improvements should be adopted. In addition, bill language should explicitly require a rigorous, experimental evaluation and clarify that the "limited" number of families that can be subject to alternative policies should be no more than the number needed to yield statistically valid results.

Finally, the current SESA draft would only permit agencies that participate in the bill's new SSRACSP initiative to apply for the rent demonstration. This would reduce the validity of the demonstration, which should be designed to assess the effectiveness of rent policy changes whether or not the families also receive employment services. As noted above, we recommend removing the limitations on the applicability of SESA's inspection and rent provisions, including the demonstration provision.

The Family Self-Sufficiency (FSS) program encourages work and saving among voucher holders and public housing residents through employment counseling and financial incentives. Unfortunately, residents of units assisted through project-based Section 8 are ineligible for the program. SESA addresses this omission by providing project-based Section 8 owners the option to offer tenants the opportunity to participate in an FSS program operated by a public housing agency, if one is available that will admit the families.

The SESA FSS provision would be much stronger, however, if it included a series of other improvements that have previously been proposed. The current SESA draft does not include a provision of the June draft that gave project-based Section 8 owners the option to operate an independent FSS program if no existing PHA-operated program is available. This omission could limit significantly the self-sufficiency opportunities SESA would provide for provide for project-based Section 8 recipients.

In addition, the new SESA draft does not include promising HUD proposals that would facilitate the merger of FSS programs for public housing and voucher families, and make other improvements. The bill also omits important provisions contained in a bipartisan voucher reform bill considered in previous sessions of Congress — the Section 8 Voucher Reform Act (SEVRA) — and in FSS reform legislation previously introduced by Chairman Biggert that would establish a predictable formula for allocating funding to support FSS staff.

The current SESA draft adds a new provision not included in the June version of SESA that would allow housing agencies to require low-income families receiving public housing or voucher assistance to pay the higher of $75 or 12 percent of the local fair market rent (FMR), even if this is more than 30 percent of the family's income.[6] Under current law, such minimum rents are limited to $50. The higher minimum rents in SESA would be optional for housing agencies, but agencies could face considerable pressure to impose them to make up for funding shortfalls.

Raising minimum rents could significantly harm some of the poorest housing assistance recipients. Housing agencies are required to provide hardship exemptions from minimum rents, but these exemptions are usually available only to families that apply for them. If a housing agency does a poor job of making families aware of the exemption or if households (which will include a substantial number of people with mental and physical disabilities) simply do not manage to apply, vulnerable families could be placed at risk of homelessness or other severe hardship.

It is not clear that even the increase in minimum rents to $75 is justified, but permitting minimum rents up to 12 percent of the FMR is particularly problematic. This would allow minimum rents in excess of $200 for a sizeable share of housing assistance recipients, sharply increasing the number of families that the rents affect. Families in high-cost metropolitan areas and with three or more children would face the highest minimum rent and be at the greatest risk of hardship.

The MTWIEPA draft would permit — and could potentially be read to require — HUD to admit an unlimited number of agencies to the Moving-to-Work demonstration. MTW permits participating agencies to operate outside many of the statutes and regulations that normally apply to the public housing and voucher programs and to receive funding through special formulas established by HUD. Many of 35 agencies that have been admitted to MTW to date are well run. Some have used their flexibility under MTW to increase efficiency or implement experimental policies that deserve testing. Nonetheless, a major expansion of MTW — whether it is an unlimited expansion like that in MTWIEPA or a large capped expansion like that included in the 2009 SEVRA bill (which would have allowed HUD to admit 80 agencies) — would very likely result in significant adverse consequences, and there is no persuasive rationale to support it.

Despite its name, MTW is not focused primarily on promoting work and has been ineffective in testing policies to achieve this goal. Some MTW agencies have implemented policies such as funding for employment services, time limits, work requirements, and changes to rent rules. But there is no reliable evidence that these policies have effectively promoted work.

This is largely because MTW was not designed as an experimental demonstration, in which randomly selected families receive housing assistance under alternative policies and are compared to otherwise similar families who receive assistance under regular program rules. Such a design would require agencies to take on the added task of administering two sets of rules. But it is a standard feature of successful policy demonstrations, because without such a design it is very difficult to determine the actual effects of experimental policies.

For example, some MTW agencies have established "flat rents" that are the same regardless of a tenant's income. Such rents are meant to encourage work, but could also increase hardship and even homelessness (because the poorest families may be charged more rent than they can afford) or waste money (because higher income families receive larger subsidies than they need). Without an experimental evaluation, however, it is difficult to determine whether trends in employment, hardship, or costs stemmed from the flat rent policy or from other factors (such as local economic conditions or changes in the makeup of the agency's caseload).

Similarly, some MTW agencies have implemented work requirements. These policies too carry major potential tradeoffs. Work requirements could cause some families to work who would not otherwise, but risk causing hardship if vulnerable families where the adults cannot work or cannot find jobs lose assistance. In addition, work requirements could substantially raise administrative burdens. Many housing agencies have pointed out that the limited community service requirement now in place in public housing has significantly raised their administrative costs. To fully assess work requirements, it would be necessary to conduct an experimental evaluation of the effects on families and to carefully assess the impact on administrative costs.

Moreover, MTW is an inefficient (as well as ineffective) way to test policies, due to several flaws that would be difficult to fix without radically altering the program. It allows agencies to expose all assistance recipients to untested policies rather than only the small share needed to determine the policies' effects. Moreover, HUD has permitted agencies to extend the application of experimental policies indefinitely whether or not the policies being tested prove effective. In addition, MTW institutes other harmful features (such as the costly funding arrangements described below) that are often unrelated to the policies being tested.

By contrast, housing policy demonstrations such as Moving-to-Opportunity (MTO) and Jobs Plus have generated a far greater quantity of useful findings than MTW, with much less disruption to tenants. These demonstrations involved only about 5,000 families each (across multiple sites and including control groups) and were carried out over five years or less. By comparison, the current MTW demonstration already affects more than 400,000 families, a number that would rise sharply under the proposed expansion.

A series of demonstrations conducted in the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program prior to the enactment of welfare reform legislation in the 1990s offers another example of rigorously evaluated policy experiments that generated substantial policy lessons. Like MTW, these demonstrations tested a range of largely state- and locally-designed experimental policies, including alternative benefit formulas, time limits, work requirements, and investments in job training and other services. But because the federal government consistently required rigorous evaluation, the experiments produced a wealth of information about the impacts of various policies.

If Congress wishes to identify which self-sufficiency policies work and should be scaled up, it could do so most effectively by creating targeted, temporary, and rigorously evaluated demonstrations — not by expanding MTW, which has failed for over a decade to generate meaningful policy findings. The SESA rent policy demonstration moves toward this more promising approach.

Proponents of expansion argue that the flexibility MTW provides can enable agencies to streamline their programs and operate more efficiently and effectively. MTW, however, is not an effective mechanism to achieve streamlining. Where added streamlining and flexibility are warranted, they should be provided to all agencies, not to a select group as MTW would do. SESA would streamline substantial aspects of program administration for all agencies (if the provision limiting the streamlining of rent and inspection rules to agencies participating in the new SSRACSP program is removed).

MTW, by contrast, would often give participating agencies far more flexibility than is desirable to operate outside of the rules Congress established to ensure that housing assistance funds are spent effectively. For example, federal rules that give voucher holders the right to move anywhere in the country where there is a voucher program — not just within the jurisdiction of the agency that issued the voucher — play a key role in making vouchers effective. This right allows a worker who is laid off but finds a new job in a different county to use a voucher to move to an apartment within commuting distance of the new employer. Similarly, a victim of domestic violence can flee an abuser, an elderly person or person with a disability can move closer to a needed caregiver, and a family with children can move to an area with better schools — all without losing their vouchers.

Eight MTW agencies, however, use their flexibility under MTW to limit or eliminate voucher portability. [7] Such restrictions may simplify administration for the agency and benefit local landlords, but they also make vouchers less responsive to the employment and other needs of low-income families, deny building owners in other communities the opportunity to rent to the affected families, and overturn a fundamental policy decision Congress made in designing the voucher program.

In addition, as noted above, extending broad flexibility to a large number of agencies in some areas — such as rent policy — could reduce the efficiency of housing assistance programs by creating an unwieldy patchwork of local rules.

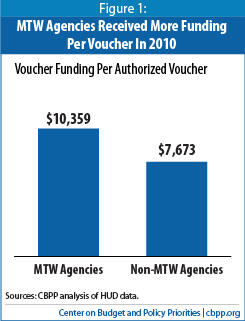

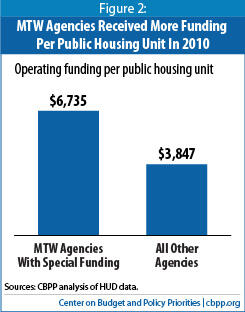

The special funding arrangements provided to MTW agencies are, on average, far more generous than those provided to non-MTW agencies. As shown in Figure 1, MTW agencies received 35 percent more voucher funding per authorized voucher in 2010 than other agencies. In 2009, when Congress enacted a funding policy (a "reserve offset") that reduced funding for many non-MTW agencies, MTW agencies on average received 52 percent more funding per authorized voucher. Similarly, 10 MTW agencies received public housing operating funding in 2010 under special formulas, which on average provided 75 percent more funding per unit than other agencies received.

The added funding for MTW agencies has sometimes come at the expense of other agencies. When voucher or public housing appropriations fall short of the amount for which agencies are eligible, HUD reduces funding for all agencies on a prorated basis. Consequently, each additional dollar that MTW agencies receive directly reduces funding levels for other agencies.

In 2009, for example, HUD reduced funding levels by 0.9 percent, forcing non-MTW agencies to assist more than 15,000 fewer families than they could have with full funding. If MTW agencies had been subject to the same funding formula as other agencies, the voucher appropriation would have been adequate to cover the full amount for which all agencies were eligible, and the proration would not have been necessary. This was also true of a 0.5 percent proration applied in 2010, and will likely be true of a 1 percent proration HUD announced it is implementing in 2011.

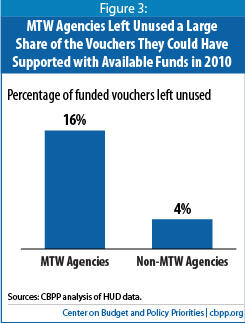

In addition to receiving added funding, MTW agencies manage their funds under incentives that are very different from those faced by other agencies. Non-MTW agencies' voucher subsidy funding and administrative funding levels reflect the number of families they assisted in the previous year, so these agencies have a strong incentive to assist as many families as they can. Most MTW agencies, by contrast, are funded under special block grant formulas that give each agency a fixed dollar amount that rises annually by the rate of inflation.[8] This eliminates the incentive for agencies to provide voucher assistance to as many families as possible, since agencies can leave funds unspent or use them for other purposes with no effect on their funding for the following year. The statute establishing MTW requires agencies to assist "substantially the same" number of families as they would without the funding flexibility MTW provides (and MTWIEPA reaffirms this), but HUD has not enforced that requirement in a meaningful way.[9]

In 2010, MTW agencies shifted approximately $400 million to other purposes or left the funds unspent. As Figure 2 shows, MTW agencies in 2010 left idle 16 percent of the vouchers they could have supported with the funds they received, compared to just 4 percent for non-MTW agencies. As a result, more than 45,000 low-income families at MTW agencies were left without voucher assistance.

[10] A non-MTW agency that left vouchers unused in this manner would face a sharp cut in funding, because its voucher subsidy and administrative funding are based on actual subsidy costs and the number of families they assist. But MTW formulas generally eliminate these incentives, allowing agencies to leave vouchers unused without adverse consequences.

MTW agencies have shifted voucher funds to a variety of purposes, including building or rehabilitating public or other affordable housing and contracts with local organizations to provide services. These expenditures may have benefits, but they do not extend housing assistance to additional families — or at least not enough to offset the vouchers left unused. As a result, in 2009 MTW agencies assisted about 9 families per $100,000 in public housing and voucher funding, compared to 15 families at non-MTW agencies, as shown in Figure 3.[11]

Many MTW agencies have used voucher funds to rehabilitate or replace public housing or build new affordable housing. Such investments could increase an agency's ability to provide housing assistance in the future to some degree, and the estimates above of the number of families assisted per dollar of federal funding do not take into account added families assisted in the future. It is unlikely, however, that the impact will come close to offsetting the number of families MTW agencies leave unassisted today.

Studies by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and others have found that even over the long run, developing affordable housing is generally a less cost-effective way to help families afford housing than vouchers.[12] Moreover, significant amounts of MTW agencies' 2009 housing development expenditures occurred after the units were completed and occupied, to cover debt incurred during construction and rehabilitation. These expenditures are an effective way to finance development, but they will not enable an agency to assist more families than it did in 2009.

MTW agencies have used voucher funds for a variety of purposes other than development and rehabilitation of public and other affordable housing, including services for low-income families and agency administrative costs. It is difficult to assess these transfers fully, since data on the amount of funds shifted to various purposes are limited and the initiatives funded with the transfers have not been rigorously evaluated. Many of these initiatives appear to be well designed to meet real needs in the community. Nonetheless, the broad authority that MTW gives agencies to shift funds from rental assistance to other purposes raises a series of risks, which are likely to grow if MTW is dramatically expanded.

Due to funding limitations, only about one in four eligible families receive housing assistance, and most communities have long waiting lists for assistance. A recent HUD analysis of Census Bureau data found that 7.1 million renter households had "worst-case housing needs" in 2009, meaning that they had incomes below half of the local median income, either lived in substandard housing or paid housing costs that exceed 50 percent of their income, and did not receive housing assistance.[13] MTW policies that result in fewer families receiving assistance aggravate this already deep shortage.

The consequences of leaving needy families unassisted can be severe. A rigorous study has found, for example, that low-income families that were not offered vouchers were substantially more likely to experience homelessness, be compelled to double up with another family, or move frequently from one apartment to another, than similar families who were offered vouchers.[14] Homelessness, crowding, and housing instability, in turn, have been shown to be closely linked to poor health and development outcomes for children. [15]

Most MTW agencies appear to administer their programs responsibly. But because MTW permits large transfers of voucher funds with only limited reporting on how they are spent, the potential for waste or misspending is high. This potential is lower at non-MTW agencies, which must use their funding for vouchers or see it reduced the next year and must collect, verify, and report to HUD detailed information about voucher holders and their homes. Moreover, it is far more difficult for HUD to oversee the widely varying programs at MTW agencies than to oversee non-MTW public housing and voucher programs, which are largely consistent from one agency to the next.

The experience of the Philadelphia Housing Authority illustrates what can happen when an agency misuses the leeway MTW provides. The authority transferred more than $300 million out of its voucher program from 2005 to 2010, and in 2010 left about 9,300 low-income families unassisted as a result. Beginning in 2010, a series of reports surfaced that substantial funds were used for unnecessary payments to outside law firms, gifts for employees, social events, and unnecessary or excessively expensive improvements to housing developments and administrative buildings. [16] In March 2011, HUD placed the authority under administrative receivership, and several federal investigations have been completed or are underway. There is no indication that Philadelphia is representative of MTW agencies, but an expansion of MTW would increase the risk that Philadelphia's experience would be repeated.

MTW permits housing agencies to shift housing assistance resources into areas that are often funded using state or local resources, including development subsidies and employment or social services. When this occurs, a state or locality could then withdraw state or local funds from these areas (or withhold funds they would otherwise use to increase expenditures in these areas) and use the funds to fill gaps elsewhere in its budget.

The result of this practice, known as supplantation, is that funding for housing assistance drops, but funding for the related areas to which funds are transferred is no higher than it would have been otherwise. Unlike certain other federal programs where a risk of supplantation exists, MTW does not impose a "maintenance of effort" requirement to ensure that states and localities maintain expenditure levels in related areas. In fact, MTW agencies are not required to report whether state and local funds for related purpose have been reduced or even the details of how the agency spent its own funds, so it is impossible to know to what degree supplantation has occurred. The risk of supplantation has grown in recent years, however, as states and local governments have struggled with difficult fiscal environments.

MTW agencies have used substantial funds that congressional appropriators provided for voucher subsidies to low-income families to instead support activities covered by voucher administrative funds and the public housing operating and capital funds. In both cases, therefore, there is a strong justification for providing added resources to make up for funding shortfalls. The need for such resources, however, extends to all agencies that administer public housing and vouchers, not just those in MTW.

The best way to address the shortfalls would be for Congress to increase appropriations for voucher administration and public housing, not to expand MTW to grant more agencies flexibility to shift funds away from vouchers for low-income families. Indeed, by granting select agencies a backdoor way to reallocate funding, MTW expansion reduces the pressure on Congress to provide adequate appropriations in these areas and could make it less likely that non-MTW agencies will receive adequate funding.

The drafts of SESA and MTWIEPA offer very different approaches to supporting self-sufficiency among housing assistance recipients. By permitting an unlimited expansion of MTW, MTWIEPA would allow HUD and state and local housing agencies to sweep aside many of the basic federal standards that have made housing assistance programs effective and allow housing assistance funds to be shifted in ways that are likely to result in many fewer families receiving assistance. Yet there is no reason to expect that an expanded MTW program would do a better job of identifying effective self-sufficiency policies than the existing demonstration has.

SESA, by contrast, would make targeted changes to promote self-sufficiency while leaving in place rules that have proven beneficial. Major improvements are needed to SESA's self-sufficiency provisions. Most importantly, participation in the SSRACSP initiative should not be condition for housing agencies to benefit from SESA's rent and inspection provisions, and the increase in the minimum rents agencies can adopt — and especially the provision permitting minimum rents to be raised to 12 percent of the local FMR — should be removed.