|

Revised September 28, 2006

NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN HEALTH SAVINGS ACCOUNTS:

HOUSE COMMITTEE APPROVES BILL, MAJOR NEW GAO STUDY

On September 27, the House Ways

and Means Committee approved H.R. 6134, which would make Health Savings Accounts

(HSAs) more attractive as tax shelters for high-income individuals. Ways and

Means Chairman Bill Thomas (R-CA) stated that the bill could be enacted before

the 109th Congress adjourns. The bill is particularly disturbing in light

of an important new Government Accountability Office (GAO) report finding that

HSAs already are used disproportionately by affluent households and provide

disproportionate tax subsidies to them. The GAO report also provides new

evidence that HSAs could raise the cost of health care for less healthy

Americans by encouraging “adverse selection.”

What Are Health Savings

Accounts?

Established by the 2003 Medicare

drug legislation, Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) are accounts in which

individuals who have a high-deductible health policy can save money to pay

out-of-pocket health expenses. In tax year 2006, someone who enrolls in a

health plan with a deductible of at least $1,050 for individual coverage and

$2,100 for family coverage may establish an HSA.

HSA contributions are tax

deductible and may be placed in stocks, bonds, or other investment vehicles,

with the earnings accruing tax free. Withdrawals also are tax exempt if used

for out-of-pocket medical costs. No other savings vehicle offers both

tax-deductible contributions and tax-free withdrawals. And since

there are no income limits on HSA participation, affluent individuals whose

incomes exceed IRA participation limits — or who have “maxed out” their IRA or

401(k) contributions — can use HSAs to shelter more money. As a result,

many analysts have warned that HSAs are likely to be used extensively as tax

shelters by high-income individuals.

What Would the House HSA Bill

Do?

The bill approved by the Ways and

Means Committee would make HSAs even more attractive as tax shelters to

high-income households, in two ways:

- Relaxing the HSA contribution

limits. Currently, the amount that HSA participants can contribute to their

account each year is limited to the amount of the deductible in their health

insurance plan or the statutory limit on HSA contributions ($2,700 for

individuals and $5,450 for family coverage in 2006), whichever is lower.

The bill would allow all HSA participants to contribute up to the statutory

limit, irrespective of the deductible in their health plan.

Under the bill, some

high-income individuals who may wish to use an HSA as a tax shelter but whose

contributions are currently limited by their health plan’s deductible would be

able to contribute considerably more to their account. The likely result would

be to induce more high-income individuals to establish an HSA and to increase

the amounts that high-income HSA participants contribute. Furthermore, since

these individuals would be contributing funds not needed to cover health

costs incurred under their deductible, a substantial share of the additional

contributions would likely be used for tax-sheltering purposes.

This provision also

would likely lead to an increase in health care spending by individuals

with HSAs, undermining the rationale advanced for HSAs in the first place — that

they can reduce health care expenditures. There are two reasons why:

-

HSAs provide a tax subsidy for

virtually any out-of-pocket health care costs, including elective

procedures not normally covered by health insurance. By enabling individuals to

“overfund” their HSAs (contributing up to $5,450 annually for family coverage

while facing a deductible as low as $2,100 for such coverage), the bill could

encourage some people to spend a portion of their excess HSA balances on

elective services they would not otherwise consume.

-

HSA proponents have argued that the

high deductibles required under HSA-eligible plans encourage people to limit

their health care use to necessary, cost-effective services (although many

health care analysts question this claim). The current rule tying the HSA

contribution limit to the amount of the deductible gives HSA participants an

incentive to choose plans with higher deductibles, because the higher the

deductible, the larger the HSA contribution allowed. By severing this link, the

House bill would encourage individuals with HSAs to switch to plans with lower

deductibles, thereby weakening whatever incentives the high deductibles may

provide in curbing health care expenditures, and leaving HSAs exposed primarily

as tax shelters.

- Allowing one-time transfers of

funds from Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) to HSAs. Under current

law, individuals generally may not withdraw funds from IRAs for purposes other

than retirement without paying income taxes and a financial penalty. The House

bill would add an exemption to this rule by allowing individuals, on a one-time

basis, to transfer funds from an IRA to an HSA without tax or penalty, so long

as their total contributions to the HSA that year do not exceed the HSA

contribution limit.

This would allow people to convert several thousand dollars in tax-deferred

savings into entirely tax-free savings by shifting them from an IRA to a

traditional HSA. That is because unlike IRA withdrawals in retirement, which

are taxed as ordinary income, HSA withdrawals in retirement are tax-free as long

as they do not exceed a family’s out-of-pocket health care costs that year.

The change would

primarily benefit high-income individuals, since they are the people most likely

to make such a transfer. Data on IRAs show that high-income individuals are

much more likely to have IRA accounts than the less affluent and make larger

contributions to them.

The change also could

open the door to future exemptions that allow people to transfer funds from IRAs

— or 401(k) plans, which have the same tax-deferred treatment as traditional

IRAs — to HSAs on an ongoing basis. That could cause substantial

long-term budgetary damage. If individuals can avoid taxation of significant

savings by transferring them from tax-deferred IRAs and 401(k)s to tax-free

HSAs, the already alarming budget forecast for coming decades will grow still

worse.

What Does the New GAO Report

Tell Us About Actual HSA Use?

Until recently, little or no solid data have been available to assess whether

HSAs are being used disproportionately by affluent individuals. The new GAO

study breaks new ground, by providing data from the Internal Revenue Service on

all Americans who made HSA contributions in 2004. The GAO study also contains

data from three large employers who offer both HSA-eligible plans and

traditional coverage on which option their employees have chosen. (To

supplement these data, the GAO conducted focus groups of individuals at these

three firms.) Finally, the GAO reviewed data on enrollment in HSA-eligible

plans from several national surveys of employers.

As

the first solid, broad-based data on actual HSA use by people in different

income groups, the GAO findings are now the premier data in the field to

determine whether HSAs are being disproportionately used by high-income

households. The GAO’s principal findings are:

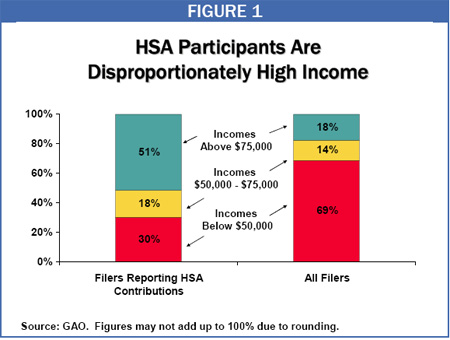

- HSA participants are

disproportionately high-income. People with adjusted gross income of more

than $75,000 made up 51 percent of all HSA participants in 2004 but only 18

percent of all tax filers under age 65. (At the other end of the income scale,

people with incomes below $30,000 made up half of all tax filers but only 16

percent of all HSA participants.) Moreover, the average adjusted gross income

of tax filers reporting HSA contributions in 2004 was $133,000, as compared to

$51,000 for all tax filers under age 65.

-

Many HSA participants appear to be

using their accounts purely as a tax shelter. About 55 percent of tax

filers reporting HSA contributions in 2004 did not withdraw any funds

from their accounts and “appeared to use their HSA as a savings vehicle,”

according to the GAO. Moreover, the GAO reported that when individuals are

given a choice between HSA plans and more traditional health insurance plans,

HSA plans attract “higher-income individuals with the means

to pay higher deductibles and the desire to accrue tax-free savings.”

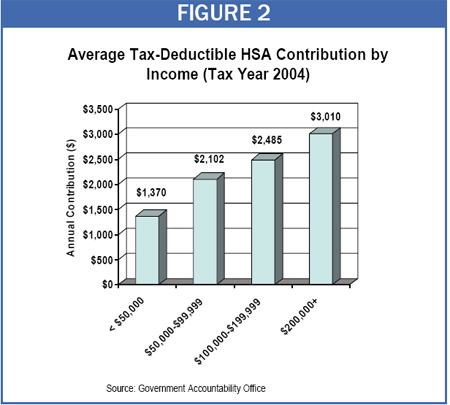

- High-income HSA participants

contribute much more to their accounts than other participants. HSA

participants who had incomes over $200,000 contributed an average of $3,010 to

their accounts in 2004, more than double the average contribution of $1,370 for

HSA participants who had incomes below $50,000. The fact that higher-income

individuals not only are more likely to have HSAs but also contribute more to

their accounts further skews the tax benefits of HSAs to high-income households,

as does the fact that higher one’s tax bracket, the richer the subsidy that HSAs

provide.

- HSAs reduce costs for the healthy,

but raise costs for the less healthy. The GAO compared the total

out-of-pocket costs (premiums, deductibles, and co-payments) that would be

incurred under the traditional plans and HSA-eligible plans offered by three

large employers. It found that healthy enrollees who use little health care

would tend to incur lower costs under the HSA-eligible plans, while people who

use more extensive health care services would tend to incur higher costs under

the HSA plans. Consistent with this finding, HSA participants in the GAO focus

groups said they would recommend HSAs to healthy people but would not

recommend such plans “to those who use maintenance medication, a chronic

condition, have children, or may not have the funds to meet the high

deductible.”

- HSAs are likely to provoke “adverse

selection.” Health policy experts have long counseled policymakers to avoid

the separation of healthier and less-healthy people into separate insurance

arrangements. The GAO report essentially warned that HSAs may bring this about

on a significant scale: “when individuals are given a choice between

HSA-eligible and traditional plans . . . HSA-eligible plans may attract

healthier individuals who use less health care or, as we found, higher-income

individuals with the means to pay higher deductibles and the desire to accrue

tax-free savings.” When less-healthy individuals are no longer pooled with

healthier people, they can become too costly to insure, leading to an increase

in the number of Americans with below-average health who are uninsured or

underinsured.

- HSAs have not led to greater

consumer “shopping” for health care. The GAO found that “contrary to the

hopes of CDHP [Consumer-Directed Health Plan] proponents, few of the

HSA-eligible plan enrollees who participated in our focus groups researched cost

before obtaining health care services,” other than for prescription drugs. The

GAO noted that accordingly to CDHP proponents, such research is necessary if

HSAs and other consumer-driven health care approaches are going to reduce health

care spending, as proponents claim.

In sum, evidence suggests that HSAs already are

of disproportionate benefit to high-income taxpayers and are being used by many

participants primarily as tax shelters. The House bill would

exacerbate both of these problems.

End Notes:

For a more complete discussion of the issues in this summary, see the

following Center reports: Edwin Park and Robert Greenstein, “GAO Study

Confirms Health Savings Accounts Primarily Benefit High-Income Individuals,”

September 20, 2006, and Edwin Park, Robert Greenstein, and Joel Friedman,

“House Bill Would Make Health Savings Accounts More Attractive as Tax

Shelters for High-Income Individuals,” revised September 28, 2006. The House

bill also contains several smaller HSA provisions.

An individual making such a transfer would have to remain enrolled in a

HSA-eligible high-deductible health plan for at least 12 months.

|