PAYING SOCIAL SECURITY BENEFITS:

WHERE WILL THE MONEY COME FROM AFTER 2016?

by Robert Greenstein and Richard Kogan

| PDF of this report If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

The interim report of the President's Social Security commission portrays Social Security as facing a crisis starting in 2016, the year in which Social Security benefit costs will exceed Social Security tax revenues. As a number of Social Security experts have explained, Social Security itself does not face problems in 2016, because it will have accumulated $5 trillion in U.S. Treasury bonds by that time. The Social Security Trustees project that the Social Security Trust Fund will receive more than $300 billion in interest payments on the bonds in 2016 and run a surplus of $285 billion that year.(1)

This has prompted a question: if Social Security can continue paying full benefits for more than two decades after 2016 because the interest it will earn on its bonds and the proceeds it will later receive from redeeming these bonds will cover the growing cost of Social Security benefits, where will the rest of the government secure the money to make the interest payments and buy back the bonds? The rest of the government already is paying substantial interest to the Social Security Trust Fund today, and the amount it pays will grow each year through 2025. These growing interest payments help the Trust Fund cover the rising cost of Social Security benefits. Hence, the question, stated more precisely, is: when the cost of Social Security benefits reaches the point in 2016 that it exceeds Social Security tax revenue, where will the rest of the government find the money to cover the growing interest payments to the Trust Fund, and more fundamentally, to cover the growing cost of Social Security benefits?

The Social Security commission's report (and several recent op-ed articles by supporters of private accounts) contends that starting in 2016, one or more of four developments must occur: other government programs will be cut, taxes will be raised, Social Security benefits will be reduced, or the government will run deficits. The commission's report argues that one of these developments has to occur: where else will the money come from?

But the commission's report is mistaken. As the analysis presented below shows, if the Social Security surplus is walled off and devoted to paying down the publicly held debt (with exceptions in years when the economy is weak), the savings the federal government will realize in interest payments on the debt will more than cover the increased Social Security costs. In short, the Treasury will be paying interest to Social Security instead of paying interest to private bondholders.

| If the Social Security surplus is walled off and devoted to paying down the debt, except in years when the economy is weak, interest payments on the debt will be reduced substantially. These interest savings will more than cover the increase in Social Security costs in 2016 and for a number of years thereafter. |

This will not hold true, of course, if the annual surpluses run by the Social Security Trust Fund are used to a significant degree for purposes other than paying down debt. Today, the greatest risk that the annual Social Security surpluses will be used for purposes other than debt reduction is not a risk that these surpluses will be used to fund regular government programs — an approach that both parties now shun except during economic downturns — but the risk that these surpluses will be used to finance private accounts. If the Social Security Trust Fund surpluses are used to finance private accounts rather than to pay down the publicly held debt, the debt will not be reduced as much, and as a result, interest payments on that debt will be higher than otherwise would be the case. Under such an approach, there will be less savings in interest payments on the debt to offset the cost that the Treasury will incur in paying interest to the Social Security Trust Fund and later in redeeming Social Security's bonds.(2)

Social Security Costs and Interest Payments on the Debt

In the past few years, the federal budget outside Social Security has been in balance, and the annual surpluses in the Social Security Trust Fund have been used to pay down the publicly held debt. If this policy is maintained, then both before and after 2016, the savings in interest payments on the debt from devoting the Social Security surplus to debt reduction will exceed the added costs the federal government will bear in continuing to pay full Social Security benefits.

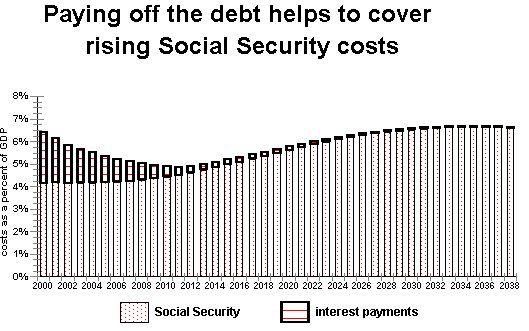

- In fiscal year 2000, interest payments on the publicly held debt equaled 2.3 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Social Security expenditures equaled 4.1 percent of GDP. Together, they equaled 6.4 percent of GDP.

- If the Social Security Trust Fund surpluses are saved and

used to pay down the publicly held debt to the level that Federal Reserve Chairman Alan

Greenspan has suggested the debt can safely be reduced, interest payments on the debt will

fall to 0.2 percent of GDP in 2016. This represents a decline of 2.1 percent of GDP

between 2000 and 2016. (Note: interest payments will fall to 0.2 percent of GDP in 2016

even if part of the Social Security surpluses are used to help finance other government

costs, rather than to pay down debt, during years when the economy turns down.(3))

The Social Security Trustees project that in 2016, Social Security costs will increase to 5.1 percent of GDP, an increase of 1.0 percent of GDP over the 2000 level.

- The decline of 2.1 percent of GDP in interest payments on the publicly held debt between 2000 and 2016 substantially exceeds the increase of 1.0 percent of GDP in the cost of Social Security benefits over this period. Thus, the savings in interest payments on the debt that will result from devoting the Social Security surpluses to debt reduction will substantially exceed the Treasury's added costs in paying full Social Security benefits. Together, Social Security expenditures and payments of interest on the publicly held debt will equal 5.3 percent of GDP in 2016, significantly below the 2000 level of 6.4 percent of GDP.

This also holds true for a number of years after 2016. In 2025, for example, interest payments on the publicly held debt will have edged down further to 0.1 percent of GDP, a decline of 2.2 percent of GDP from the 2000 levels. Social Security costs are projected to be 6.2 percent of GDP that year, or 2.1 percent of GDP above current levels.

These interest savings will not fully cover the increase in Social Security costs forever. By a point in the mid-2020s, the increase in Social Security costs will start to exceed the savings in interest payments on the debt. Even in 2038, however, the savings in interest payments on the debt will equal 90 percent of the increase in Social Security costs (see graph).

In other words, the answer to the question of where the government will find the money to make increased interest payments to Social Security after 2016 to cover growing Social Security costs is that the government will be able to use funds freed up by the reduction in interest payments on the publicly held debt as a result of devoting the Social Security reserves to debt reduction. (Stated differently, it is true that in 2016 and subsequent years, rising Social Security costs will require revenue increases or spending reductions elsewhere in the budget, measured as a share of GDP, or else result in a re-emergence of permanent deficits. But what the Social Security commission has failed to acknowledge is that the required reduction in federal spending can be accomplished through reductions in payments on the publicly held debt achieved by devoting the Social Security surplus to debt reduction, rather than through cutting programs.)

Alarmist Rhetoric in Commission Report The Commission's interim report notes that if Social Security's deficits (excluding its interest earnings) are financed in 2016 and subsequent years by cutting other government programs, reductions of $17 billion will be needed in 2016. The report declares that "making up Social Security's 2016 deficit by cutting other spending would require eliminating programs the combined size of Head Start and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC)." In fact, if the Social Security surplus is used for debt reduction, the savings in interest payments on the debt will be $450 billion in 2016 (compared with what the interest payments would have been if the cost of these interest payments had remained at 2000 levels, measured as a percentage of GDP). This amount substantially exceeds the $17 billion by which Social Security benefit costs will exceed Social Security tax revenues that year. If programs such as Head Start and WIC are squeezed in 2016, it will be primarily because of the tax cut, not Social Security. If the provisions of the tax cut are extended, their cost in 2016 will be approximately $380 billion, or about 22 times the amount by which Social Security benefit costs will exceed Social Security tax revenue. (The Commission report attempts to finesse this point in a way that obfuscates the issue. The report says that if total federal spending — including Social Security benefits — remains constant as a share of the Gross Domestic Product, other programs would have to be cut starting in 2016 — or taxes raised, Social Security benefits reduced, or deficits run — to cover the amount by which Social Security benefit costs will exceed Social Security tax revenues in those years. But federal spending is not expected to remain constant as a share of GDP between now and 2016; it is expected to drop significantly, largely because of the reduction in spending for interest payments on the debt. In 2001, total federal spending is expected to equal 17.8 percent of GDP. Under the budget resolution that Congress approved in May, spending would drop to 16.2 percent of GDP by 2011. Under the alternative budget resolution that Senate Democrats unsuccessfully offered this spring, federal spending would have dropped to 16.4 percent of GDP by 2011. There is no budget plan on the horizon under which federal spending — which has been dropping as a share of GDP since 1992 — would not continue to fall, largely because of the continued reduction in interest payments on the publicly held debt.) |

Preserving the Social Security surpluses also helps Social Security in another way, by increasing national saving. Higher national saving will result in a larger economy and, as a consequence, a larger flow of revenue to the federal government and the Social Security Trust Fund. A Congressional Budget Office analysis issued last year, which provides estimates through 2040, projects that the economy will be larger and levels of federal revenue higher over the next four decades if the Social Security surplus is saved than if it is consumed. Specifically, the economy will be almost 10 percent larger by 2040 if the Social Security surpluses are saved, and total federal revenues will be 12 percent, or more than $1 trillion, higher in that year.(4)

| Using the Social Security surpluses to pay down debt will reduce the strain that paying Social Security benefits will place on the rest of the budget in coming decades. |

To be sure, simply preserving the surpluses that Social Security is now running will not be sufficient for the long term. To restore long-term Social Security solvency and do so in a way that ultimately does not place excessive strain on the rest of the budget, changes in Social Security must be made. Such changes should be enacted sooner rather than later so they can be phased in gradually over many years.(5) But Social Security does not face a crisis in 2016, and the dimensions of the Social Security shortfall over the next 75 years — 0.7 percent of GDP, according to the Social Security actuaries and trustees — is hardly of a crisis magnitude if it is dealt with in the near future. Furthermore, walling off the annual Social Security surpluses (except when the economy is weak) and using these surpluses to pay down the publicly held debt will significantly reduce the strain that paying Social Security benefits will place on the rest of the budget over the next several decades.

End Notes:

1. See Henry J. Aaron, Alan S. Blinder, Alicia H. Munnell, and Peter R. Orszag, "Perspectives on the Draft Interim Report of the President's Commission to Strengthen Social Security," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and the Century Foundation, July 23, 2001.

2. This assumes that under such an approach, the same Social Security surplus dollars would both be credited to the Social Security Trust Fund and deposited in private accounts. If this occurred, the Treasury would still have to pay the same amount of interest to the Trust Fund but would not have secured as much in savings in interest payments on the debt, because the debt would not have been paid down as substantially.

To be sure, if private accounts were linked to reductions in Social Security benefits, the reductions in Social Security benefits eventually would ease some of the burdens on the Treasury. But that would not occur for several decades — until those who are young today and had paid into private accounts for several decades began to retire. In the years before then, the crunch on the rest of government would be intensified; the amounts diverted from Social Security to private accounts would exceed the reductions in Social Security benefits, while less debt reduction would have occurred.

It may be noted that if Social Security surpluses were diverted to private accounts without the Trust Fund being credited with the same dollars, the burden would shift. There would be less burden on the Treasury but a greater burden on the Trust Fund. While the Treasury would have to spend more on interest payments on the publicly held debt because the debt would not have been paid down much, the Treasury would not owe as much in interest payments to the Trust Fund. However, the financing shortfall in the Social Security Trust Fund would be much greater. If payroll tax revenue equal to two percent of payroll were diverted to private accounts without also being credited to the Trust Fund, the year in which Social Security benefit costs would exceed Social Security tax revenue would move forward from 2016 to 2007, and the year in which the Trust Fund would become exhausted and Social Security would be insolvent would be accelerated from 2038 to 2024. In addition, Social Security's long-term deficit would double from about 1.9 percent of payroll over the next 75 years to 3.9 percent of payroll. Coupling such an approach with measures to protect benefits for those currently retired or nearing retirement would necessitate exceptionally deep reductions in Social Security benefits if such a plan were to restore long-term solvency. (For a further discussion of these issues, see Peter R. Orszag and Robert Greenstein, "Financing Private Accounts in the Aftermath of the Tax Bill," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 21, 2001.)

3. If the entire Social Security surplus is used to pay down debt every year, the debt will be reduced to the level Chairman Greenspan has recommended several years before 2016. As a result, if a portion of the surplus is used for other purposes in years when the economy is weak — as may be the case in fiscal year 2001, for example, when a tiny fraction of the Social Security surplus may used for other purposes — interest payments still should decline to 0.2 percent of the economy by 2016.

4. The Long-Term Budget Outlook, CBO, October 2000, tables 4 and 7.

5. For an excellent discussion of possible changes in Social Security, see Chapter 6 of Henry J. Aaron and Robert D. Reischauer, Countdown to Reform: The Great Social Security Debate, The Century Foundation, 2001.