|

July 28, 2006

HOUSE ESTATE TAX PROPOSAL HAS ESSENTIALLY THE SAME LARGE LONG-TERM COST AS EARLIER VERSION:

Phase-Ins Mask Costs, But Underlying Policy Remains Unchanged

by Joel Friedman and Aviva Aron-Dine

Just five weeks after passing legislation that would drastically reduce the estate tax (H.R. 5638), the House of Representatives is considering another estate-tax proposal. The House passed H.R. 5638 in the hope that it would attract the needed 60 votes in the Senate, but Senators who oppose repealing most or all of the estate tax did not embrace the House alternative, viewing it as too costly.

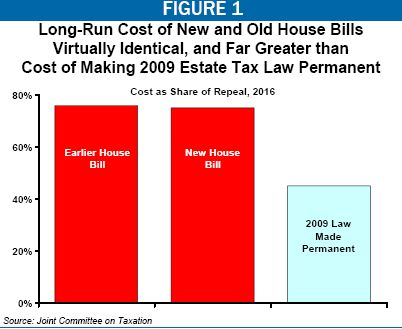

Joint Committee on Taxation estimates show that the new House proposal, unveiled the evening of July 28, would be just as costly over the long run. While the new proposal phases in its estate tax reductions gradually so as to limit revenue losses in the first few years, the Joint Tax Committee estimates suggest that the long-term cost would amount to75 percent of the cost of full repeal, as compared with 76 percent in the case of the earlier House legislation (see Figure 1).

Moreover, this estimate that the long-term cost would be 75 percent as large as that of full repeal rests on the assumption that the capital gains tax rate, to which a key estate tax rate would be tied, would be allowed to rise from its current 15 percent level to 20 percent after 2010 — an increase that Republican Congressional leaders adamantly oppose. If the capital gains rate remains at 15 percent, the new House estate tax proposal would cost about 80 percent as much as full repeal.

New House Proposal Uses Gimmicks to Create Illusion of Lower Cost

The new House proposal is being presented by House leaders as being $15 billion less costly than the estate-tax plan that the House passed in June. Supporters point to new Joint Tax Committee estimates that show the new proposal would result in revenue losses of $268 billion between 2007 and 2016, as compared to $283 billion for the earlier bill. But even this small difference is deceiving, as it stems from a timing gimmick employed in the new legislation.

Like the earlier House bill, the new legislation would, once it was fully in effect, exempt the first $10 million of an estate for a couple ($5 million for an individual). And like the earlier bill, the value of an estate under $25 million would be taxed at the capital gains rate, now 15 percent. The portion above $25 million would be taxed at a rate of 30 percent.

The new proposal, however, would phase in over time rather than taking full effect in 2010 as the earlier House-passed measure did. The estate tax exemption, which is $7 million per couple ($3.5 million per individual) in 2009 under current law, would rise gradually starting in 2010, reaching $10 million per couple ($5 million per individual) by 2015, with the exemption amount indexed for inflation after 2015. The top estate tax rate, which is set at 45 percent in 2009 under current law, would decrease gradually starting in 2010 to 30 percent by 2015.

Once the two proposals were both in full effect, however, their costs would be virtually identical. According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, the earlier House legislation would reduce revenues by $62.2 billion in 2016, or 76 percent of the cost of repeal in that year. The new bill would cost $61.7 billion in 2016, or 75 percent of the cost of repeal.

Moreover, like the earlier House legislation, the new bill employs an additional gimmick to mask part of its likely cost, linking the lower estate tax rate (the rate that would be levied on the value of an estate between the exemption level and $25 million) to the capital gains rate, which now stands at 15 percent. Under current law, the capital gains rate is slated to rise to 20 percent in 2011, and the Joint Tax Committee cost estimate assumes that this increase in the capital gains tax rate will be allowed to occur. If the 15 percent capital gains rate is extended after 2010 — as the Congressional Republican leadership intends — the cost of the new proposal would be higher than the official cost estimate shows.

If this occurs, the new proposal likely would lose about 80 percent of the revenue lost by full repeal.

However Costs Are Measured, Revenue Losses under New Proposal Are Very Large

As discussed in the box on page 3, the best indicator of the long-run fiscal impact of estate-tax proposals is their cost in 2016. But no matter what time period is used to assess the new House proposal’s cost, it remains very high.

- The Joint Tax Committee finds that the new proposal would cost $268 billion between 2007 and 2016. In comparison, repealing the estate tax would cost $387 billion over this period, according to the Joint Tax Committee. In both cases, these cost estimates are deceiving, however, because the proposals would not take full effect until a good part of the way through the ten-year period.

- In the first ten-year period in which the costs of estate-tax repeal would be fully felt (2012-2021), we estimate that repeal would cost $808 billion — or $1.0 trillion when the associated increases in interest payments on the debt are included. Over that same ten-year period, the new House proposal would cost $599 billion, or $753 billion when the interest costs are included. But these estimates understate the new proposal’s true long-term costs, because the full effects of the new proposal would only be felt in six or seven years of the ten years from 2012 to 2021, since the new proposal would not take full effect until 2015.

|

Reform Proposals Should Be Evaluated Based on Their Long-Term Costs

The costs of estate tax “reform” proposals are typically evaluated by comparing them to the cost of full repeal. There is some dispute, however, over how best to measure these costs. The Joint Committee on Taxation’s official estimates of the cost of repeal and various reform options cover the ten-year period from fiscal year 2007 through 2016. This means that the estimates reflect only five years of the cost of extending repeal, because that change would not take effect until 2011. Moreover, the cost of repeal is not fully reflected in the cost estimates until 2012, due to the one-year delay after an individual’s death that typically occurs before the estate tax is paid. The official cost estimates thus provide only a partial picture of repeal’s ten-year cost and of the cost of various alternative options.

As a result, it is preferable to examine the first ten years in which the costs of repeal are fully reflected in the cost estimates — 2012-2021. This can be done by taking the Joint Committee on Taxation’s estimate of the costs of an estate tax proposal for the years from 2012 through 2016. For the years after 2016, one simply assumes that the cost remains the same, measured as a share of the Gross Domestic Product, as the cost the Joint Tax Committee has estimated for 2016. Assuming that the cost of tax cuts (and spending increases) remains constant over time as a share of GDP is a standard method that budget analysts use.

Even this approach, however, can distort comparisons between proposals such as the earlier House bill, which would take full effect in 2010, and proposals such as the new House legislation, which would phase in gradually and take full effect in 2015. Another approach, which relies solely on the Joint Tax Committee estimates, is to compare the cost of various estate-tax proposals in 2016. This approach avoids the problems with using cost estimates that cover the entire 2007-2016 period. The advantage is that the 2016 estimate is the best available indicator of a proposal’s cost over the long run. The Joint Tax Committee finds that repeal would reduce revenues by $82 billion in 2016, while the new House plan would reduce revenues by $62 billion in 2016. The House proposal consequently would cost three-fourths as much as full repeal (see table below).

|

Assessing the Cost of Various Estate Tax Reforms

(using Joint Tax Committee estimates) |

|

Proposal |

Dollar Cost in 2016 |

Cost Relative to Full Repeal |

|

Repeal |

$82 billion |

100% |

|

Earlier House Bill* |

$62.2 billion |

76% |

|

New House Proposal* |

$61.7 billion |

75% |

|

2009 Law Made Permanent |

$37 billion |

45% |

| * Assumes the capital gains rate reverts to 20 percent in 2011. |

|

- The only cost-reducing measure included in the new proposal was included in the earlier House bill: the elimination of the deduction for state estate taxes. This change, which would raise a modest amount of additional revenue for the federal government, could have a severe adverse impact on states’ ability to raise revenue through state estate and inheritance taxes. Without the federal deduction, a number of these state estate and inheritance taxes — which already are under fire in a number of states — are likely to have difficulty surviving, since repeal of the deduction would significantly increase the burden of state estate and inheritance taxes. In the absence of this deduction, these state taxes are likely to be assailed as imposing a double tax burden on estates, since the federal tax would be imposed on the portion of an estate already used to pay state taxes.

In addition to eliminating the state estate tax deduction, the new proposal includes another provision of the original House bill — a provision setting the gift tax exemption equal to the estate tax exemption. This change adds to the proposal’s cost.

Finally, the new proposal, like the earlier House bill, includes other features intended to buy votes. The proposal includes special-interest tax breaks, unrelated to the estate tax, for the timber and mining industries. These measures appear designed to entice Senators from timber-producing and mining industry states to vote for the package and thereby to help secure the 60 votes needed to permanently eliminate most of the estate tax.

Proposal Spends Billions on Tax Cuts for Wealthiest Estates Relative to Continuation of 2009 Law

Many in Congress support the idea of enacting estate tax reforms that would shield the vast majority of estates from tax while preserving a significant share of estate tax revenue. One option would make permanent the 2009 levels that apply to the estate tax — a $3.5 million exemption ($7 million per couple) and a 45 percent rate. Under this approach, the estates of 997 of every 1,000 people who die would be entirely exempt from tax; only 3 in 1,000 estates would owe any estate tax. Even this option is costly; it reduces revenues by $159 billion between 2007 and 2016 and by $37 billion in 2016, according to Joint Tax Committee estimates. Based on these figures, we estimate that it would cost $366 billion between 2012 and 2021 (or $456 billion if interest costs are included). Still, it preserves about 55 percent of the revenue that would be lost over the long term by full repeal.

In contrast, the new proposal would lose three-quarters of the revenue lost by full repeal over the long run, according to Joint Tax Committee estimates, and about 80 percent of the revenue lost by full repeal if the capital gains tax rate remains at 15 percent. The Joint Tax Committee estimates show that in 2016 alone, the cost of moving from the 2009 levels to the House proposal would be $25 billion.

Yet all of the benefits of the new House proposal, relative to those of making 2009 estate tax law permanent, would flow to the 3 in 1,000 estates that are valued at more than $3.5 million for an individual and $7 million per couple. None of this $25 billion a year in added cost by 2016 would accrue to the estates of the other 99.7 percent of Americans who die. And the bulk of these added costs would go to the very largest estates, those worth far more than $7 million.

End Notes:

Elizabeth McNichol, “Estate Tax ‘Compromise’ Proposals May Endanger State Estate and Inheritance Taxes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 8, 2006.

Like the earlier House bill, the new proposal also would make automatic the $10 million estate tax exemption for married couples. Under current rules, a couple would need to engage in modest estate-tax planning for the proposed $5 million exemption per individual to translate into a $10 million exemption for a couple. |