|

Revised August 24, 2006

TREASURY DYNAMIC SCORING ANALYSIS REFUTES CLAIMS BY SUPPORTERS OF THE TAX CUTS

by Jason Furman

On July 25, the Treasury Department released a

study entitled “A Dynamic Analysis of Permanent Extension of the President’s Tax

Relief.” This study refutes many of the exaggerated claims about the tax cuts

that have been made by the President and other senior Administration officials,

the Wall Street Journal editorial page, and various other tax-cut

advocates. Contrary to the claim that the tax cuts will have huge impacts on

the economy, the Treasury study finds that even under favorable assumptions,

making the tax cuts permanent would have a barely perceptible impact on the

economy. Under more realistic assumptions, the Treasury study finds that the

tax cuts could even hurt the economy.

In addition, the study casts doubt on claims that

the tax cuts are responsible for much of the recent growth in investment and

jobs. It finds that making the tax cuts permanent would lead initially to lower

levels of investment, and would result over the longer term in lower levels of

employment (i.e., in fewer jobs).

The Treasury also study decisively refutes the

President’s claim that “The economic growth fueled by tax relief has helped send

our tax revenues soaring,” — in essence, that the tax cuts have more than paid

for themselves.

[1] Instead, under the study’s more

favorable scenario, the modest economic impact of the tax cuts would offset just

10 percent of the long-run cost of making the tax cuts permanent according

to an analysis of the Treasury study by the non-partisan Congressional Research

Service (CRS).[2]

|

Misunderstanding of the

Treasury Study Mars Some News Accounts |

| Some of the reporting on the

Treasury analysis has made a basic mistake. The Treasury study found that

making the tax cuts permanent would increase the size of the economy

over the long run — i.e., after many years — by 0.7 percent, if the

tax cuts are paid for by unspecified cuts in government programs. This is

a very small effect. If it took 20 years for the 0.7 percent increase to

fully manifest itself (Treasury officials have indicated it would take

significantly more than ten years but have not been more specific than

that), this would mean an increase in the average annual growth rate for

20 years of four-one-hundredths of one percent — such as 3.04 percent

instead of 3.0 percent — an effect so small as to be barely noticeable.

Moreover, after the 20 years or whatever length of time it would take for

the 0.7 percent increase to show up, annual growth rates would return to

their normal level — that is, they would be no higher than if the tax cuts

were allowed to expire. Several news

reports, however, mistakenly said that the Treasury found that making the

tax cuts permanent would lead to a 0.7 percentage point increase in the

annual growth rate. If true, that would be an enormous economic

benefit; it would increase the size of the economy by 40 percent after

fifty years. It would be more than fifty times larger than the 0.7

percent increase in the size of the economy over several decades that the

Treasury study actually found. |

Finally, the

conclusions in the Treasury study are based on the assumption that the tax cuts

will be paid for by deep and unspecified cuts in government programs starting in

2017. The Treasury study is consistent with other research on dynamic scoring

in finding that in the absence of such budget cuts — i.e., if the tax cuts

continue to be deficit financed indefinitely — the tax cuts would end up

weakening the economy over the long run.

The following are four key findings from the

report.

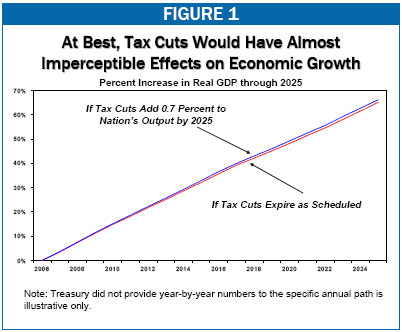

Finding #1: At best, making the tax cuts

permanent would have a barely perceptible effect on the economy.

The featured estimate in the Treasury study is

that making the tax cuts permanent would add 0.7 percent to the size of the

economy over the long run, under the unrealistic assumption that the tax cuts

are paid for by deep and unspecified reductions in government programs that

start in 2017. The report does not specify what “long run” means, but if the

higher growth rates were spread over 20 years,[3]

an ultimate increase of 0.7 percent in the size of the economy would mean an

increase of just four one-hundredths of one percent in the average annual growth

rate. For example, instead of average annual growth of 3.0 percent, the economy

would have an average annual growth rate of 3.04 percent. As shown in Figure 1,

this difference is so small as to be barely perceptible.

Moreover, the Treasury study acknowledges that

the long-run growth rate would not rise at all. The study indicates that after

some period of time (such as 20 years), the barely noticeable, slightly higher

annual average growth rate cited above would end, and the rate of economic

growth after that would merely be the same as it would be if the tax cuts

are allowed to expire.

The Treasury study casts doubt on several

widespread claims about the tax cuts. For example, supporters of the tax cuts

have credited those measures for the recent increase in investment. The

Treasury study finds, however, that making the tax cuts permanent would

initially lead to lower levels of investment. (The Treasury study does find

that if the tax cuts are paid for by cutting government programs, they would

eventually lead to higher levels of long-run investment.) In addition, the

Treasury study finds that making the tax cuts permanent would reduce long-run

labor supply (i.e., the number of people working and the number of hours they

work) by 0.3 percent, undercutting another popular argument — that the tax cuts

will help the economy by creating jobs and encouraging more work.

The Treasury study also shows results if

alternative assumptions are used regarding the responsiveness of people’s

working and saving to changes in taxes. The study finds that even if people are

much more sensitive to tax rates than economists generally assume, the size of

the economy would rise, after many years, by only 1.2 percent. Over 20 years,

this is the equivalent of an increase in the average annual growth rate of just

six one-hundredths of one percent (i.e., to an annual growth rate of 3.06

percent of GDP instead of 3.0 percent).

Moreover, the CRS study suggests that the

Treasury’s base case assumes an unrealistically high level of responsiveness of

people’s work and savings decisions to tax rates. According to CRS “the

empirical evidence… actually supports the low case somewhat more.” In the

Treasury’s “low case,” the level of long-run output eventually increases as a

result of the tax cuts by a mere 0.1 percent of GDP (rather than by 0.7 percent

of GDP), and even this tiny increase is based on the assumption that the costs

of the tax cuts are offset by dramatic (and unrealistic) cuts in government

programs.

Finding #2: The tax cuts would pay for less than

10 percent of themselves in the long run

The Treasury did not release the findings of its

model with regard to the amount of additional revenue that would be generated by

the increase in economic growth that the tax cuts are assumed to produce. But

analysis of the Treasury study by the Congressional Research Service finds that

if the tax cuts are paid for with dramatic spending cuts, then the economic

growth generated by making the tax cuts permanent would offset only 7 percent of

the initial cost of the tax cuts and 10 percent of the long-run cost. The

effect would be even smaller with assumptions CRS considers more realistic.

One straightforward way to derive such a revenue

estimate is to compare the cost of the tax cuts in the absence of any dynamic

effects to the added revenue that would result from the increased level of

economic growth the tax cuts are assumed to produce. According to CBO’s

official cost estimate, the Administration’s proposal to make the tax cuts

enacted since 2001 permanent would cost 1.4 percent of GDP annually. (This does

not include the relief from the Alternative Minimum Tax that the Administration

regularly proposes on an annual basis, which would bring the total cost to 2

percent of GDP.) The Treasury study finds that the tax cuts would raise

national output by “as much as” 0.7 percent over the long term; with tax

receipts projected to be about 18 percent of GDP, this translates into an

increase in revenues, as a result of greater economic growth, of about 0.13

percent of GDP.

Thus, under the Administration’s optimistic

dynamic-scoring scenario, the net cost of the tax cuts would equal approximately

1.27 percent of GDP annually after the dynamic effects of the tax cuts are taken

into account. This is more than 90 percent of the conventional cost estimate of

the tax cuts (see Figure 2).[4]

Moreover, the Treasury study finds that the tax cuts would have even smaller

effects on economic output, and hence presumably on tax revenues, in the first

years after they were made permanent.

This finding shreds claims that the tax cuts are

paying for themselves or offsetting a sizable fraction of their costs.

Finding #3: Tax cuts will benefit the economy

modestly only if they are paid for by large and unspecified cuts in government

programs.

The featured results in the Treasury study are

based on the assumption that government programs are cut sharply starting in

2017 in order to pay for the tax cuts. In total, government spending would have

to be reduced by the equivalent of about 1.3 percent of GDP after 2017.[5]

That would be equivalent to cutting domestic discretionary spending in half.

This is substantially larger than the budget cuts the President has proposed.

Thus, the featured Treasury estimates are estimates of the long-term economic

effects not of the tax cuts per se, but of the combination of the tax cuts that

the President has proposed and unspecified, deep program cuts that he has not

proposed.

Moreover, many low- and middle-income families

likely would lose more from the cuts in government programs made under this

scenario than they would gain from the combination of the relatively small tax

cuts they would get and the slightly expanded economy.6 An

analysis conducted in 2004 by the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax

Policy Center and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that if the

tax cuts were financed through a mechanism that would produce effects similar to

those that could occur if the tax cuts were paid for largely or entirely through

spending cuts, roughly four-fifths of U.S. households ultimately would lose more

from the budget cuts than they would gain from the tax cuts.[6]

The Treasury

study does not report how its results would change if alternative scenarios for

cutting government spending were used. Studies of generic tax cuts by

Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), the Congressional Budget Office (CBO)

and academic researchers all have found that the deficits caused by income-tax

cuts can result in a smaller economy over the long run. The Joint Committee on

Taxation, for example, found that income-tax cuts could help the economy if they

were paid for after ten years but that waiting 20 years to finance them would

result in much more debt and consequently would hurt the economy.[7]

The Treasury study does not present any analysis of what would happen under

alternative assumptions about the timing and the specific form of the assumed

program cuts. Such analysis might show that the tax cuts could hurt the economy.

Finally, the Treasury study also estimates that

if the tax cuts are financed by income-tax increases, they will reduce long-run

national output by 0.9 percent. Since the drastic cuts in programs that the

Treasury assumes in its “favorable” scenario are unlikely to materialize, under

a more realistic scenario that relies on a combination of program cuts and tax

increases, the economy would be little affected and could even be hurt.

Finding #4: The Treasury study confirms that it

is more prudent to raise taxes by a smaller amount today than to raise them by a

larger amount in the future

A standard result in economics is that it is

better to finance a given level of government spending with a “smooth” level of

taxes.[8]

For example, if the long-run budget is in deficit, it is better to act sooner

and raise taxes by a smaller amount today than to wait for the deficits to grow

so large that taxes have to be raised by a larger amount in the future. This is

a basic implication of the old adage that it is better to act sooner to prepare

for future challenges.

The Treasury study confirms this finding.

Specifically, it finds that cutting taxes today and raising them by even more in

the future to make up for the lost revenue and the larger deficits ultimately

would reduce the size of the economy (real GNP) by 0.9 percent. In other words,

the Treasury analysis finds that if one does not expect dramatic reductions in

government programs to be instituted to pay for the tax cuts, it would be better

for the economy to let the tax cuts expire.

This is consistent with the commonsense

prescription: in preparing for our future fiscal challenges, it is better for

the economy to have slightly higher taxes today (by letting some or all of the

tax cuts expire) than to wait a long time and have to raise taxes dramatically

in the future. Similarly, it would generally be preferable to make more modest

program reductions today than to make larger program cuts in the future.

End Notes:

[1] Remarks by the President on the

Mid-Session Review, July 11, 2006:

http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2006/07/20060711-1.html

[2] Jane Gravelle, Congressional Research

Service, “Comments on the Treasury Dynamic Analysis of Extending the Tax Cuts,”

July 27, 2006.

[3] According to Treasury officials,

about two-thirds of the ultimate 0.7 percent increase in the Gross National

Product would occur by 2016.

[4] The Treasury study does not include

the economic impact of repealing the estate tax. Including it could result in a

long-run “dynamic effect” that is slightly different. Economic theory does not

have a clear prediction about whether the economic impact of estate tax repeal

is positive or negative. Treasury appears to acknowledge this in its study,

where it notes, “There is considerable uncertainty regarding the likely

behavioral responses to repealing the estate tax.” Moreover, Treasury’s dynamic

scoring model assumes a “target bequest motive.” Under that theory, estate tax

repeal would likely cause people to save less — reducing long-run output and

magnifying the cost of the tax cuts — because they would not need to set aside

as much money to leave the desired amount to their heirs.

[5] Treasury assumes that the government

spending reduction would be sufficient to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio at its

2017 value. As a result, spending reductions would have to total about 1.3

percent of GDP in present value terms, the equivalent of the cost of making the

tax cuts permanent after accounting for dynamic feedback and ignoring the costs

of extending relief from the AMT.

[6] See William G. Gale, Peter R. Orszag,

and Isaac Shapiro, “The Ultimate Burden of the Tax Cuts,” Urban

Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center and the Center on Budget and

Policy Priorities, June 2, 2004. This analysis examined the relative effects of

the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts and a measure to offset the tax cuts’ cost through

budget cuts spread evenly across the U.S. population. The analysis did not

attempt to estimate economic effects of the tax cuts.

[7] For more discussion see Jason Furman,

“A Short Guide to Dynamic Scoring,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities,

revised July 26, 2006.

[8] Robert Barro, “On the Determination

of Public Debt,” Journal of Political Economy, 64, pp. 93-110. |