Conference "Marriage Penalty

Relief" Provisions Reflect Poor Targeting

Much of the Benefits Would Go to Higher-Income Taxpayers

or Those Who Already Receive Marriage Bonuses

by Iris Lav and

James Sly

|

click here for PDF version |

On July 19, House and Senate conferees reached agreement on marriage-tax-penalty relief legislation that will shortly be sent to the President. The legislation would cost $292.5 billion over 10 years.

The official cost assigned to the bill is considerably less — $89.8 billion — because the legislation provides the tax relief only through 2004 in order to satisfy Senate rules. History shows, however, that legislation of this type rarely is allowed to expire, and the Washington Post has reported that House Speaker Dennis Hastert and Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott said yesterday it would be unthinkable for Congress to allow this tax cut to expire in five years. "I don't think it ever will be reversed," Lott said.(1) The full, permanent cost of the bill thus should be considered the relevant benchmark.

Although two of the legislation's marriage penalty provisions are focused on middle- or low-income families, the bill as a whole is poorly targeted and largely benefits couples with higher incomes. The proposal's costliest provision, which accounts for more than 60 percent of of the legislation's overall cost when fully phased in, benefits only taxpayers in the top quarter of the income distribution. In addition, the bill would provide approximately two-fifths of its benefits to families that already receive marriage bonuses.

An analysis of the effects of the conference agreement prepared by the Joint Committee on Taxation shows that higher-income taxpayers would be the primary beneficiaries of the conference agreement tax relief. In 2004, when all provisions are fully in effect, the JCT analysis shows:

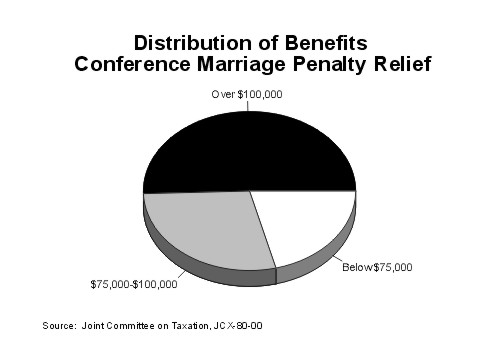

- Over half the bill's benefits when the bill is fully in effect would go to taxpayers with incomes over $100,000.

- Some 79 percent of the benefits of the bill would go to taxpayers with incomes exceeding $75,000 — the highest-income 22 percent of all taxpayers.

- The three-quarters of taxpayers with the lowest incomes, those with incomes below $75,000, would share just 21 percent of the marriage penalty relief the legislation provides.

Provisions

The conference agreement contains three principal provisions related to marriage penalties. The most costly by far of these would reduce the rates at which income is taxed for some married couples. This provision would increase for married couples the income level at which the 15 percent tax bracket ends and the 28 percent bracket begins.

Once in full effect, the proposal to expand the 15 percent tax bracket itself would approach $20 billion a year in cost. This provision would exclusively benefit taxpayers in brackets higher than the current 15 percent bracket; no other taxpayers would be touched by it. Since only the top quarter of all taxpayers — the top third of all married couples — are in brackets higher than the 15 percent bracket, only these higher-income taxpayers would benefit from the provision.

|

Provision |

Cost in billions |

Percent of Total Cost |

|

Expand 15 Percent Bracket |

$17.7 |

62% |

|

Increase Standard Deduction |

6.5 |

23 |

|

Increase EITC |

1.3 |

5 |

|

AMT Changes |

2.9 |

10 |

|

Total |

$28.3 |

100% |

|

Source: Joint Committee on Taxation, JCX-79-00, July 19, 2000 |

||

The second provision would raise the standard deduction for married couples, setting it at twice the standard deduction for single taxpayers. A third, much smaller provision would increase the earned income tax credit for certain low- and moderate-income married couples with children.

A fourth provision relates to the alternative minimum tax (AMT) and affects both married and single taxpayers; it is not specifically designed to relieve marriage penalties. This provision would permanently extend taxpayers' ability to use personal tax credits, such as the child tax credit and education credits, to offset tax liability under the alternative minimum tax.

Bill Carries High Cost Due To Poor Targeting of Marriage Penalty Relief

The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the conference agreement, without the sunset, would cost $292.5 billion over 10 years. The proposal's longer-term cost is substantially higher than this. The bill's most costly provision, which would extend the 15 percent tax bracket, would not take full effect until 2004; that reduces the bill's cost in the first 10 years. The Joint Tax Committee estimate shows that when all of the plan's provisions are fully in effect in 2010, the bill would cost $39 billion a year.

The bill's tax reductions are not focused on married families that face marriage penalties. Nearly as many families receive marriage bonuses today as receive marriage penalties, and the bill would reduce their taxes as well. Indeed, the bill would confer tens of billions of dollars of "marriage penalty tax relief" on millions of married families that already receive marriage bonuses. Approximately half of the tax reductions from the "marriage penalty relief provisions," the provisions exclusive of the alternative minimum tax changes, would go to families that currently receive marriage bonuses.

Targeted Marriage Penalty Relief Possible at Lower Cost

By contrast, the marriage penalty relief proposal contained in the Administration's fiscal year 2001 budget is significantly less costly, approximately $50 billion over ten years. This proposal, which is targeted on low- and middle-income married filers who face marriage tax penalties, would provide substantial marriage penalty relief at about one-fourth the cost of the conference agreement when both proposals were fully in effect. (This comparison excludes the cost of the AMT provisions in the conference agreement.)

End Note:

1. "Congress Tapping Surplus for Tax Cuts, Domestic Programs," The Washington Post, July 21, 2000, p. A4.