|

Revised June 23, 2006

THOMAS ESTATE TAX PROPOSAL STILL “NEAR REPEAL”:

Instead of Compromising, Proposal Tries to Have It Both Ways

By Joel Friedman and Aviva Aron-Dine

On June 22, the House of Representatives passed

estate-tax legislation (H.R. 5638), introduced by House Ways and Means Chairman

Bill Thomas, that is very similar to — and even slightly more costly than — the

most recent estate-tax proposal floated by Senator Jon Kyl. Both proposals

would cost nearly as much as permanent repeal of the estate tax, and, relative

to other reforms, such as making 2009 estate tax law permanent, both would spend

billions more on tax breaks for the largest estates. The Senate is expected to

vote on the measure before adjourning for the July 4th recess. Senate Majority

Leader Bill Frist has encouraged this process in hopes of achieving the needed

60 votes in the Senate to drastically reduce the estate tax. (This follows the

Senate’s rejection on June 8 of a motion to consider legislation that would

repeal the estate tax permanently.)

The Thomas proposal would exempt the first $10

million of an estate for a couple ($5 million for an individual), with the

exemption amount indexed after 2010. The estate tax rate would be linked to the

capital gains rate, which is currently 15 percent, but which is slated to return

to 20 percent after 2010. Under the plan, the value of an estate under $25

million would be taxed at the capital gains rate, and the portion above $25

million would be taxed at two times the capital gains rate.

In linking the estate tax rate to the capital

gains rate, Chairman Thomas has embraced a gimmick that allows his proposal to

be presented differently to groups on different sides of the estate tax debate:

it can be described as having rates of 15 percent and 30 percent, or, to make

it appear more attractive to those concerned about cost, it can be presented as

having rates of 20 percent and 40 percent. In reality, of course, the current

15 percent capital gains rate either will be extended after 2010 or it will not

be: the Thomas proposal cannot simultaneously have a top estate tax rate of

both 30 percent and 40 percent. Yet the proposal is designed with the hope of

having it both ways politically.

Whether or not the capital gains rate increases

to 20 percent, the Thomas proposal does not represent a true compromise:

- The Joint Committee on Taxation finds that the

Thomas proposal would cost $283 billion between 2007 and 2016, with a cost of

$62 billion, or 76 percent as much as full repeal, in 2016. (In contrast, the

most recent proposal offered by Senator Kyl would cost $275 billion between

2007 and 2016 and $60 billion in 2016 alone, meaning that the Thomas proposal

is even more costly — by a small amount — than the Kyl plan.[1])

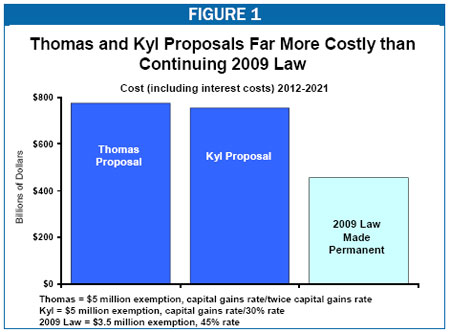

Based on Joint Tax Committee estimates, we estimate that the Thomas proposal

would cost $611 billion between 2012 and 2021 (the first ten-year period in

which its costs can be fully measured), and $774 billion if the costs of the

additional interest payments on the debt are included (see box on page 3).

- In making its estimates of the new Thomas

proposal, the Joint Tax Committee assumed that the capital gains rate would

revert to 20 percent as scheduled in 2011. (The Joint Committee must make

this assumption because its estimates must reflect current law.) This means

that even with estate tax rates of 20 percent and 40 percent, the Thomas

proposal would cost about three-quarters as much over the long run as full

repeal.

- If instead, the 15 percent capital gains rate

is extended after 2010 — as the Congressional Republican Leadership intend —

then the top estate tax rate would be 30 percent and the cost of the Thomas

proposal would be higher. Assuming that the lower capital gains rate is

extended after 2010, Joint Tax Committee estimates indicate that Thomas plan’s

cost would rise to more than 80 percent of the cost of repeal. Over the

2012-2021 period, the cost would amount to more than $820 billion, including

interest.

- If the capital gains rate is allowed to revert

to 20 percent, the Thomas proposal would cost two-thirds more than making

permanent the 2009 estate tax levels (a $3.5 million exemption — $7 million

per couple — and a 45 percent rate). This additional cost — $25 billion in

2016 alone, according to Joint Tax Committee estimates — would go entirely for

tax breaks for the 3 of every 1,000 estates that would owe any estate tax

under the 2009 levels. If the capital gains rate remains at 15 percent, the

amount by which the costs of the Thomas plan would exceed the cost of making

the 2009 levels permanent would, of course, be even greater.

- The Thomas proposal also would eliminate the

estate tax deduction for state estate taxes. This change, which would raise a

modest amount of additional revenue for the federal government, would have a

severe adverse impact on states’ ability to raise revenue through state estate

and inheritance taxes. Without the federal deduction, however, a number of

these state estate and inheritance taxes — which already are under fire in a

number of states — are likely to have difficulty surviving, since repeal of

the deduction would significantly increase the burden of state taxes. It would

likely be perceived as imposing a double tax burden on estates, since the

federal tax would be imposed on the portion of an estate already used to pay

state taxes.[2]

|

Reform

Proposals Should Be Evaluated Based On Their Long-Term Costs |

|

The costs

of estate tax “reform” proposals are typically evaluated by comparing them

to the cost of full repeal. There is some dispute, however, over how best

to measure these costs. The Joint Committee on Taxation’s official

estimates of the cost of repeal and various reform options cover the

ten-year period from fiscal year 2007 through 2016. This means that the

estimates reflect only five years of the cost of extending repeal, because

that change would not take effect until 2011. Moreover, the cost of

repeal is not fully reflected in the cost estimates until 2012, due to the

one-year delay after an individual’s death that typically occurs before

the tax is paid. The official cost estimates thus provide only a partial

picture of repeal’s ten-year cost and of the cost of various reform

options.

As a

result, it is preferable to examine the first ten years in which the costs

of repeal are fully reflected in the cost estimates — 2012-2021. This can

be done by taking the Joint Committee on Taxation’s estimate of the costs

of an estate tax proposal for the years from 2012 through 2016. For the

years after 2016, one simply assumes that the cost remains the same,

measured as a share of the Gross Domestic Product, as the cost the Joint

Tax Committee has estimated for 2016. Assuming that the cost of tax cuts

(and spending increases) remains constant over time as a share of GDP is a

standard method that budget analysts use.

Another

approach, which relies solely on the Joint Tax Committee estimates, is to

compare the cost of various estate-tax proposals in 2016. This approach

avoids the problems with using cost estimates that cover the entire

2007-2016 period. The advantage is that the 2016 estimate is a good

indicator of a proposal’s cost over the long run. The Joint Tax Committee

finds that repeal would reduce revenues by $82 billion in 2016, while the

Thomas plan would reduce revenues by $62 billion in 2016. The Thomas

proposal consequently would cost three-fourths as much as full repeal (see

table below).

|

Assessing the Cost of Various Estate Tax

Reforms

(using Joint Tax Committee estimates) |

|

Proposal |

Dollar Cost in 2016 |

Cost Relative to Full Repeal |

|

Repeal |

$82 billion |

100% |

|

Thomas Proposal* |

$62 billion |

76% |

|

Kyl Proposal* |

$60 billion |

74% |

|

2009 Law Made Permanent |

$37 billion |

45% |

|

* Assumes the capital gains rate reverts

to 20 percent in 2011. |

|

In addition to

linking the estate tax rate to the capital gains rate, the Thomas proposal would

also set the gift tax exemption equal to the estate tax exemption, raising it to

$5 million, a change that adds to the proposal’s cost.

[3]

Finally, the

Thomas proposal includes other features intended to attract votes. In

particular, the proposal includes a special-interest tax break for the timber

industry. That measure, which is unrelated to the estate tax, would reduce the

capital gains taxes owed on certain timber sales. It appears designed to entice

Senators from timber-producing states to vote for the package and thereby to

help secure the 60 votes needed to permanently eliminate most of the estate

tax. While the estate and gift tax provisions of the proposal are permanent,

the timber provisions would expire at the end of 2009 (though they likely would

be extended, at additional cost, in future years).

Thomas Proposal Spends Billions on Tax Cuts

for Wealthiest Estates Relative to Continuation of 2009 Law

Many in Congress support the idea of enacting

estate tax reforms that would protect the vast majority of estates from tax,

while preserving a significant share of the estate tax revenue. One option

would make permanent the 2009 levels that apply to the estate tax — a $3.5

million exemption ($7 million per couple) and a 45 percent rate. Under this

approach, the estates of 997 of every 1,000 people who die will be entirely

exempt from tax; only 3 in 1,000 estates will owe any estate tax. Even this

option is costly; it reduces revenues by $159 billion between 2007 and 2016 and

by $37 billion in 2016, according to Joint Tax Committee estimates, and these

estimates suggest that it would cost $366 billion between 2012 and 2021, or $456

billion if interest costs are included. Still, it preserves about 55 percent of

the revenue lost by full repeal over the long term.

In contrast, even if the capital gains rate were

allowed to revert to 20 percent, the Thomas proposal would lose about

three-quarters of the revenue lost by full repeal over the long run, according

to Joint Tax Committee estimates — and would cost 68 percent more than making

permanent the 2009 estate-tax levels. The Joint Tax Committee estimates show

that in 2016 alone, the additional cost of moving from the 2009 levels to the

Thomas proposal would be $25 billion. If the 15 percent capital gains rate is

extended, the added cost of the Thomas plan would be still higher (about $30

billion in 2016).[4]

Over the 2012-2021 period, the Thomas plan (assuming a 15 percent capital gains

rate) would lose about $285 billion more in revenues than making the 2009 levels

permanent (or about $370 billion when the associated interest costs are

included).

Finally, all of the additional benefits of the

Thomas proposal, relative to the cost of making the tax permanent at the 2009

levels, would flow to the 3 in 1,000 estates that are valued at more than $3.5

million for an individual and $7 million per couple, with the bulk of the added

cost going for larger tax breaks for the largest of these estates.

End Notes:

[1] The most recent Kyl proposal featured an indexed $10 million

per couple exemption, a rate linked to the capital gains rate for the value of

an estate below $30 million, and a rate of 30 percent for the value of the

estate above $30 million. For a more detailed discussion of this Kyl proposal,

see Joel Friedman and Aviva Aron-Dine, "New Joint Tax Committee Estimates Show

Modified Kyl Proposal Still Very Costly: True Cost Partially Masked," Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities, June 13, 2006.

[2] Elizabeth McNichol, “Estate Tax ‘Compromise’ Proposals May

Endanger State Estate and Inheritance Taxes,” Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities, June 8, 2006.

[3] The Thomas plan also would make automatic the $10 million

estate tax exemption for married couples. Under the current rules, a couple

would need to engage in modest estate-tax planning for the proposed $5 million

exemption per individual to translate into a $10 million exemption for a couple.

[4] For additional discussion of the difference between the Thomas

proposal and 2009 law made permanent, see Joel Friedman and Aviva Aron-Dine,

“High Cost of Thomas Proposal Reflects the Low Effective Tax Rates Estates Would

Face: Proposals Benefits Would Go Primarily to Largest Estates,” Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities, revised June 23, 2006. |