|

June 14, 2006

NEW ESTATE TAX ANECDOTES DREDGE UP OLD MYTH THAT THE ESTATE TAX CLAIMS HALF OF AN ESTATE

By Aviva Aron-Dine and Joel Friedman

Opponents of the estate tax often claim that it forces estates to pay half of their assets in taxes. For example, during the Senate debate on the estate tax earlier this month, Senator Jon Kyl told the story of a businessman whose family allegedly had to pay “half of the value of [his] company to the government.” Senator Kyl went so far as to compare the estate tax to the feudal system, under which the family of the deceased had to turn over a portion of his property to the king in order to retain his land.

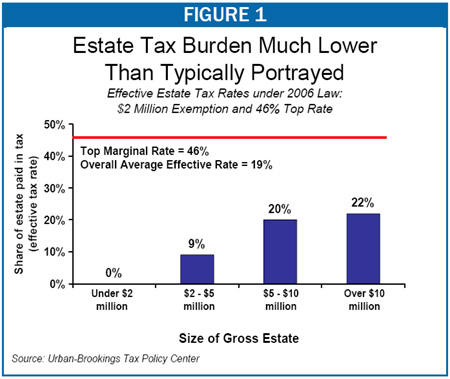

Senator Kyl’s example, and his far-fetched analogy, bear little relation to the reality of the U.S. estate tax. At the current $2 million exemption level ($4 million per couple) only one in every 200 people who die in 2006 will owe any estate tax at all. Among the few estates that do pay the tax, the “effective” tax rate — that is, the percentage of the estate that is actually paid in taxes — will be much lower than the top estate tax rate, which is currently set at 46 percent. According to the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center, the average effective estate tax rate on estates that owe any estate tax at all will stand at only 19 percent in 2006, which means that fewer than one fifth of the assets of a taxable estate generally will be needed to pay the tax. For taxable estates valued at less than $5 million, the effective rate will be less than 10 percent this year.

These Tax Policy Center estimates are consistent with IRS data on effective rates for previous years, when the top estate tax rate was even higher. For instance, according to the IRS, the average effective estate tax rate in 2004 was 20 percent, even though these estates faced a top statutory rate of 49 percent.

Effective Rate Lower Than Top Rate

Why is the effective tax rate so much lower than the top tax rate established in law? First, estate taxes are due only on the portion of an estate’s value that exceeds the exemption level, not on the entire estate. For example, at today’s $2 million exemption level, a $2.5 million estate would owe estate taxes on $500,000 at most. (Couples can generally use both spouses’ exemptions so as to shield $4 million from tax). Second, a large portion of the estate’s remaining value can be shielded through available deductions (for charitable bequests and state estate taxes paid, for instance).

Additional options to mitigate the impact of the estate tax are available to family-owned businesses and farms, which can take advantage of special “valuation discounts” and can spread their estate tax payments over 14 years. Further, many large estates employ planning devices (such as insurance trusts) to shrink the size of the taxable estate. For these reasons, the Tax Policy Center and IRS estimates may well overstate the effective tax rates that estates actually pay.

Estate Tax Plays Legitimate and Important Role in Overall Tax System

Supporters of repealing the estate tax often imply that failure to repeal the tax will mean a return to a 55 percent top rate — which leads them to the disingenuous charge that the estate tax would confiscate 55 percent of an estate. But the estate tax changes enacted in 2001 have reduced the top marginal rate significantly, and it will fall further, to 45 percent next year. The 55 percent top rate would in theory return in 2011, when the changes enacted in 2001 expire (although even then, the average effective rate would be well below 50 percent). But virtually all reasonable reform proposals would retain the lower rates that are currently on the books (as well as the higher exemption levels).

For example, one prominent and reasonable reform measure would make permanent the estate tax rules that will be in effect in 2009, when the first $3.5 million per individual — $7 million per couple — will be entirely exempt from the tax, and a top rate of 45 percent will apply to the taxable portion of estates. The Tax Policy Center projects that under these parameters, the average effective tax rate for the few estates that will owe any tax at all — the estates of the wealthiest 3 of every 1,000 people who die in 2009 — will be 17 percent. It is not necessary to repeal the estate tax, or to reduce the top rate to very low levels (such as the 15 percent capital gains rate), to ensure that the effective estate tax rate does not reach “confiscatory” levels.

Moreover, unlike payments made under a feudal system, the estate tax is one component of a tax system that funds our democratic government and the services it provides. Revenue raised by the estate tax helps pay for essential programs, from health care to education to defending the nation. If the estate tax were repealed or substantially reduced, then other taxpayers — presumably a more numerous and less well-off group than those paying the estate tax — would have to foot the bill for these programs, face cuts in government services, or bear the burden of a higher national debt.

Like other Americans, the very wealthy benefit from public investments in areas such as defense, education, health care, scientific research, and infrastructure, and they rely even more than others on the government’s protection of individual property rights (since they have much more to protect). As Bill Gates, Sr., a prominent estate tax advocate, explains, “The reason the estate tax makes so much sense is that there is a direct relationship between the net worth people have when they pass on and where they live. The government that protects their business activities, the traditions that enable them to rely on certain things happening, that’s what creates capital and enables net worth to increase.”[1] It seems only fair that people who have prospered the most in this society help to preserve it for future generations through the payment of a reasonable level of taxes by their estates.

End Notes:

[1] “Excerpts from Bill Gates, Sr., during a June 1 CBPP Conference Call Briefing on the Estate Tax. |