TANF'S "UNCOUNTED" CASES:

More than One Million Working Families Receiving

TANF-funded Services Not Counted in TANF Caseload

by Shawn

Fremstad and Zoë Neuberger

| PDF of this report Related Reports |

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

An often-cited but misunderstood statistic is that welfare caseloads have fallen by more than 50 percent over the past five years. While it is true that fewer families are receiving cash assistance, it is not the case that the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program is helping 50 percent fewer families now than it did five years ago. States have used TANF funds to provide work supports and other services to an increasing number of families who are not counted in TANF caseload statistics because they do not receive welfare checks.(1) A very conservative estimate based on the limited data available from most states is that more than one million working families receive TANF-funded services without being counted in the caseload. More complete data from a few states suggests the actual number of "uncounted" families substantially exceeds one million.

The size of this "uncounted caseload" has important implications for TANF reauthorization. Although the value of the block grant has eroded substantially due to inflation, some have argued that increasing the TANF block grant above its current frozen level is not warranted given the decline in cash assistance caseloads. This argument fails to take into account the large number of non-welfare families receiving TANF-funded work supports, such as child care, transportation assistance, and job training. These supports and other services help former welfare recipients as well as other low-income families make ends meet and stay off of welfare. This argument also fails to consider the increasing number of families receiving services designed to meet the new "family formation" purposes of the TANF law — promoting marriage, preventing nonmarital pregnancies, and encouraging the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.

As policymakers consider the appropriate level of TANF funding for states, they will need to look beyond cash assistance caseload statistics and consider the broader group of families now participating in TANF-funded programs in order to gain an accurate measure of future state funding needs.

Background

The 1996 welfare law gave states new discretion to use federal and state TANF funds for non-cash services, such as child care, transportation subsidies, state earned income tax credits, and employment services.(2) These benefits and services can be provided to families receiving monthly cash assistance checks as well as to other poor families who do not receive cash assistance or have left the cash assistance rolls. States also can use TANF funds to serve individuals and families who never would have been eligible for assistance in the AFDC program (TANF's predecessor program) including low-income working families whose income levels may be modestly above the poverty line and non-custodial parents. Every state now uses TANF funds to serve low-income families who do not receive cash assistance, although the range of services provided and the number of families served varies by state.

Congress also expanded the goals of the TANF program. The primary purpose of AFDC was to provide financial assistance to needy dependent children, and to a lesser extent, to help families become self-sufficient through work. In enacting TANF, Congress retained the basic assistance goal of AFDC, strengthened the work goals, and added a new set of program goals related to family formation that were not part of AFDC — promoting marriage, preventing nonmarital pregnancies, and encouraging the formation and maintenance of two-parent families. As a result, most states now devote TANF funds to activities in these areas. For example, last year, 38 states reported devoting a portion of their federal and state TANF funds to nonmarital pregnancy prevention.

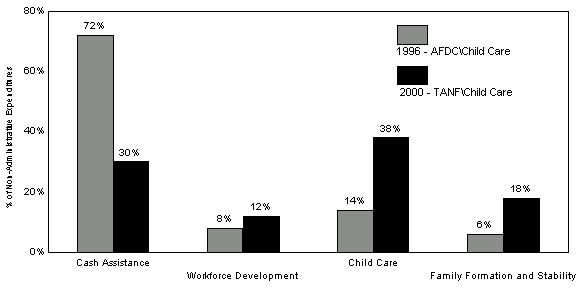

The shift in the types of benefits provided is illustrated by changes in the nature of state spending under TANF. Under the AFDC program, states spent 76 percent of state and federal funds on cash assistance in fiscal year 1996.(3) By contrast, states spent less than 40 percent of TANF funds in fiscal year 2001 on cash assistance.(4) Most of the remaining funds were used to provide work supports, especially child care, and services to strengthen families.

Table 1:

Welfare and Child Care Spending Trends in the Midwest, 1996 and 2000(5)

(Includes TANF and Child Care Block Grants)

The extent of this change is illustrated in a recent report prepared jointly by TANF state administrators in seven midwestern states (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin). The administrators analyzed TANF and child care block grant spending data in their states and grouped non-administrative expenditures into five general categories: cash assistance, child care, workforce development, low-income tax supports, and family formation and stability. As Table 1 shows, cash assistance expenditures fell from 72 percent of spending in fiscal year 1996 to 30 percent of spending in fiscal year 2000, while expenditures in each of the other spending categories increased by 50 percent or more. Some of the increase in child care spending is attributable to increases in federal child care funding since 1996, however, this increase is not driving the trend illustrated in Table 1. The share of AFDC\TANF funds devoted to child care increased at a rate comparable to the overall child care spending increase in these states. And nationally, the share of AFDC\TANF non-administrative expenditures devoted to child care increased from 4.5 percent in 1996 to 20.9 percent in 2000.(6)

In spite of this expansion of program goals and the dramatic shift in the range of benefits that are provided and the types of families that receive them, when the federal government reports on the size of the "TANF caseload" it retains the AFDC program's caseload definition and only counts persons receiving monthly cash assistance checks. Thus, families that receive TANF-funded benefits and services — including child care, transportation assistance, employment services, state earned income tax refunds, diversion assistance in lieu of a monthly welfare check, and most other services and benefits — but do not receive a monthly welfare check are left out of official "caseload" statistics.(7)

More than One Million Families Receiving Services in TANF-Funded Programs Not Included in TANF Caseload

The number of families receiving services in TANF-funded programs that do not receive welfare checks and as a result are not counted in the TANF caseload is quite substantial. Because states generally are not required to report data on such families to the federal government, estimates of the total number of families served with TANF funds must be derived from the limited state data that is available. A very conservative estimate, based primarily on a recent report by the General Accounting Office (GAO), is that more than one million families receiving services in TANF-funded programs are not counted in the TANF caseload. For reasons explained below, this estimate substantially understates the number of uncounted families. More complete data available from a few states suggest that the actual number of families receiving services in TANF-funded programs without being counted is much higher than one million families.

GAO surveyed 25 states to determine to determine how many families receive TANF-funded services, but are not counted in TANF caseload statistics.(8) The 25 states in the GAO survey provide a good estimate of the situation nationally because they received 84 percent of TANF funds in fiscal year 2001 and represent about 87 percent of the TANF cash assistance caseload. GAO asked states for unduplicated counts of the average monthly number of families who received services in TANF-funded programs in 2001, but did not receive cash assistance. Because states often commingle TANF funds with other funds to provide a particular service, a TANF-funded program was only included in GAO's count if at least 30 percent of its funding came from TANF. Unfortunately, only two states (Indiana and Wisconsin) were able to provide unduplicated counts of participants across more than one TANF-funded program.(9) To avoid duplication in the 23 states that were not able to provide unduplicated counts, GAO limited its count to a single TANF-funded program that provided services to non-welfare families in each state, generally the TANF-funded program in each state with the most participants.

GAO estimated that at least 830,000 additional families in the 25 states it surveyed — 46 percent more families than are counted in the TANF cash assistance caseload of 1.8 million families in these states — received services in TANF-funded programs without being counted in the TANF caseload. If the percentage of "uncounted cases" in the states that GAO did not survey is roughly the same as in states that GAO did survey, about 138,000 additional families receive services in TANF-funded programs without being counted in the caseload. The GAO estimate also did not include families in "separate state programs," including several such programs that provide TANF-like cash assistance and welfare-to-work services to two-parent families.(10) In California alone, more than 50,000 two-parent families receive benefits in a separate state program.

Combining GAO's estimate (830,000), its application to other states (138,000), and California's separate state program for two-parent families (50,000) yields more than one million families receiving TANF-funded benefits and services who are not counted in the TANF cash assistance caseload (830,000 + 138,000 + 50,000 = 1,018,000).

Because it is limited to only one TANF-funded program in 23 of the 25 states surveyed, GAO's count clearly understates the number of families receiving services in TANF-funded programs. More accurate estimates were obtained from two states — Indiana and Wisconsin — that were able to provide GAO with unduplicated participant counts across multiple (but not all) TANF-funded programs. GAO found that TANF caseloads in both states would more than double if families receiving services, but not cash assistance, in TANF-funded programs were included. Even these estimates understate the number of families served in these three states since none of the estimates include participants in all of the programs that provide TANF-funded services. While the Indiana estimate includes most, but not all, of the programs funded with TANF funds, the Wisconsin estimate excludes most of the programs funded with TANF dollars.

It should be noted that the GAO methodology counts a family as having received a TANF-funded service if it participated in a program that was supported with TANF, even if the program also received funding from other sources. (Although GAO excluded programs in which TANF funds accounted for less than 30 percent of the total funding). In effect, it counts families whose benefits are only partially funded with TANF. In this sense, the "uncounted" cases in the GAO count are not directly comparable to a TANF cash assistance case, which is typically fully funded with TANF (and state MOE funds). GAO notes, however, that even for the services in its study in which the cost is not fully funded with TANF dollars, the TANF-funded portion of the costs tends to be significant. For example, in the child care programs in the GAO survey, monthly child care subsidies averaged $499 per family with TANF funds accounting for $266 of the monthly average cost of the subsidy. Even with this limitation, the GAO estimate of the size of non-welfare caseload in TANF is likely to be a substantial underestimate as illustrated by more complete data from Indiana and Wisconsin. Indiana was able to limit its count to families receiving services solely funded with TANF. The number of families receiving services solely funded with TANF in that state exceeded the number of families receiving TANF cash assistance. In Wisconsin, three of the four programs included in its count were solely funded with TANF. More than 80 percent of the funding for the remaining program (child care) in Wisconsin came from TANF. (See text box for more information on Indiana and Wisconsin.)

What Kinds of

TANF-Funded Services The GAO report does not detail the types of services included in its count. Data obtained from two states provide additional insight into the number of families served in TANF-funded programs other than cash assistance. In Wisconsin, about 43,000 individuals received TANF-funded cash assistance in an average month in the fall of 2001. More than 56,000 additional individuals were served in the state's TANF program but not counted in the caseload. This unduplicated count of individuals receiving services in programs funded with TANF but not counted in the TANF caseload, includes:

In addition, many other Wisconsin families participate in several other TANF-funded programs, including after-school programs, the state's earned income tax credit, and youth apprenticeship and other work-based learning programs. In Indiana, about 47,000 families received TANF-funded cash assistance in an average month in the fall of 2001. More than 47,000 additional families were served in the state's TANF program but not counted in the caseload. This unduplicated count of families receiving TANF-funded services, but not counted in the TANF caseload, includes:

In addition, many other Indiana families participate in several other TANF-funded programs, including the state's earned income tax credit, an individual development account program, and TANF-funded vocational rehabilitation services. |

Moreover, if the more precise estimates for Indiana and Wisconsin are extrapolated to all the states, nationally more than 2.1 million families could be receiving services in TANF-funded programs without being counted in the official TANF caseload. In light of this potential, an estimate of one million families is quite conservative.

Implications for the TANF Funding Debate

The size of TANF's "uncounted caseload" has important implications for the current reauthorization debate about the appropriate level of TANF funding. In order to assess future state funding needs, policymakers need to have a more accurate understanding of how many families are actually "touched" by TANF.(11)

The 1996 law based each state's TANF block grant level on its historical AFDC spending. Because TANF funding was not indexed for inflation, the value of the TANF block grant — and the amount of services and benefits it can purchase — has declined by more than 11 percent since 1997. Even though state spending in TANF in fiscal year 2001 exceeded the amount of block grant funds states received that year, some have argued that increasing the TANF block grant above its current frozen level is not warranted given the decline in official caseloads. This argument fails to take into account the broader population of low-income families now served in TANF-funded programs and the expanded array of supports and services provided to families. Most of these supports and services help former welfare recipients as well as other low-income families make ends meet and stay off of welfare. Other TANF-funded services help reduce nonmarital pregnancies and promote the maintenance of two-parent families. In order for states to maintain their current level of these services and benefits, the value of the block grant would need to keep pace with inflation.

TANF Funds Used to

Extend Welfare-to-Work Services to More In addition to using TANF funds to provide work supports and

services to non-welfare families, states have increased spending on those families that

remain on the official cash assistance rolls by providing welfare-to-work services to a

greater portion of their caseload. Many states also are providing more intensive services

to families. A recent Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation study documents how four

large urban counties — Cuyahoga (Cleveland), Los Angeles, Miami-Dade, and

Philadelphia — used TANF funds to expand program capacity and increase the number of

cash assistance recipients enrolled in welfare-to-work programs, even as overall welfare

caseloads in each of these counties declined.a In all four counties, the

percentage of the adult welfare caseload participating in welfare-to-work activities more

than doubled between 1995-96 and 1999-2000. For example, in Los Angeles County, the number

of families enrolled in the county's welfare-to-work program increased from 34,363 in

1995-96 to 102,442 in 1999-2000. In addition to increasing the number of enrolled

families, three of the four sites increased the amount of funds they spent per

participating adult on welfare-to-work services, suggesting that they also had increased

the intensity of services. For example, in Cuyahoga County, welfare-to-work program

expenditures (excluding child care) rose from $588 per adult in 1997-98 to $1,308 in

1999-2000. |

Moreover, the Administration has proposed significant changes to the TANF work participation rates that apply to families receiving cash assistance, including requiring states to place a substantially higher share of cash assistance recipients in work activities and increasing the number of hours recipients would have to participate in work activities to be counted fully toward the rates. States would need to increase spending significantly on their cash assistance caseload to meet these proposed requirements. One recent analysis estimates that states would need to spend an additional $15 billion between 2003 and 2007 to meet the Administration's work requirements.(12) This figure includes $7 billion in additional work program costs and $8 billion in additional child care costs. Similarly, the California Legislative Analyst's Office recently estimated that California alone would incur net additional costs of about $2.8 billion between 2003 and 2007 under the proposal.(13)

In spite of these substantial new costs, the Administration provides no new funds for states. Some have argued that states would not need additional funding to implement the proposal because the decline in cash assistance caseloads has left states with sufficient funds to meet the additional costs. However, as the GAO report shows, at the same time that states reduced their TANF cash assistance caseloads, they increased the number of families receiving non-cash services and support. As a result, 30 states and the District of Columbia are now spending at or above the current level of their annual TANF block grant.(14) Without additional funds states would need to reduce the number of families receiving non-cash services and supports in order to increase spending on cash assistance recipients. As TANF program administrators in Maryland explained in a survey conducted by the National Governors' Association and the American Public Human Services Association: " . . . since no additional funds are included in the [Administration's] proposal, local departments would be forced to dismantle effective programs that reduce non-marital births, improve job retention, encourage completion of secondary education by teenagers and young adults and reduce substance abuse."(15)

Conclusion

A very conservative estimate, derived primarily from data collected by the General Accounting Office, is that at least one million families receiving services in TANF-funded programs are not counted in the TANF caseload. More complete data available from a few states suggests that the actual number of non-welfare families receiving services on a monthly basis in TANF-funded programs without being counted substantially exceeds one million families. As policymakers consider the appropriate level of TANF funding for states, they will need to look beyond cash assistance caseload statistics and consider the broader group of families now participating in TANF-funded programs in order to gain an accurate measure of future state funding needs.

Appendix

| AFDC | TANF | |

| Program Purposes | Encourage the care of dependent children in their own homes by providing financial assistance to needy dependent children and their parents. | 1) Provide assistance to needy families. 2) Promote job preparation, work and marriage. 3) Prevent out-of-wedlock pregnancies. 4) Encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families. |

| Allowable Benefits and Services | Cash assistance. Child care and employment services for cash assistance recipients. Emergency assistance. |

States have broad discretion to provide a

variety of benefits and services, including: -cash

assistance |

| Potentially Eligible Population | Very low income families with children.

Income eligibility limits below 50 percent of poverty in most states. Two-parent participation subject to more restrictive federal eligibility rules than single-parent families. Noncustodial parents not eligible. Youth eligibility limited to teen parents and children of parents receiving AFDC cash assistance. |

Generally, needy families with children. No

federally defined income limit. Several states provide certain benefits and services to

families with incomes up to 200 percent of poverty. No separate federal restrictions on two-parent eligibility. Most states do not impose stricter eligibility restrictions on two-parent families. States may provide benefits and services to noncustodial parents. States may provide benefits and services to youth regardless of whether they are teen parents or children of parents receiving TANF. |

End Notes:

1. As used in this paper, the term "TANF funds" includes both federal TANF funds and state funds, known as "maintenance-of-effort" or MOE funds, that states are required to spend in order to receive federal TANF funds.

2. See the Appendix for a table that summarizes some of the key differences between AFDC and TANF.

3. Sheila R. Zedlewski, et al., TANF Funding and Spending across the States, in Welfare Reform: The Next Act, The Urban Institute, 2002 (eds. Alan Weil and Kenneth Finegold).

4. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of fiscal year 2001 TANF spending data reported by states to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

5. Midwest Welfare Peer Assistance Network, TANF Spending Patters in the Midwest, January 2002. This table excludes expenditures on low-income tax supports, which accounted for 2 percent of TANF non-administrative spending in 2000. The Midwest Welfare Peer Assistance Network's analysis includes state and federal child care funds.

6. Sheila R. Zedlewski, et al., TANF Funding and Spending across the States, in Welfare Reform: The Next Act, The Urban Institute, 2002 (eds. Alan Weil and Kenneth Finegold).

7. For further discussion of this point, see Rebecca Swartz, Redefining a Case in the Postreform Era: Reconciling Caseload with Workload, Focus, Institute for Research on Poverty, 2002.

8. See U.S. General Accounting Office, Welfare Reform: States Provide TANF-Funded Services to Many Low-Income Families Who Do Not Receive Cash Assistance, Statement of Cynthia M. Fagnoni, Managing Director, Education, Workforce, and Income Security Issues, before the Committee on Finance, U.S. Senate, April 10, 2002, GAO-02-615T. GAO surveyed the following states: Arizona, California, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin.

9. North Carolina also provided an unduplicated count across several programs, but its unduplicated count excluded child care. More families received TANF-funded child care than the unduplicated count of families receiving other TANF-funded services, so GAO only included the child care program in its estimates.

10. Separate state programs are programs funded solely with state dollars that count toward the "maintenance-of-effort" requirement that states must meet to draw down federal TANF funds.

11. The size of the uncounted caseload also has implications for other issues that are part of the reauthorization debate, including data reporting and state accountability for performance. See Thomas L. Gais, Welfare Reform Findings in Brief, The Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government, March 1, 2002, and Rebecca Swartz, Redefining a Case in the Postreform Era: Reconciling Caseload with Workload, Focus, Institute for Research on Poverty, 2002. Gais notes that "[TANF r]eporting requirements focus on the cash assistance caseload, a small and dwindling proportion of the population served under TANF and fail to capture the broader population of the working low-income families who are served but not on cash assistance." Swartz argues that "[c]ontinuing to judge the success of a broad program by a small sliver of those served signals that the expanded role states have embraced is unimportant." She recommends "redefining" the TANF caseload to include a broader segment of the families served in TANF-funded programs.

12. Mark Greenberg, Elise Richer, Jennifer Mezey, Steve Savner, and Rachel Schumacher, At What Price? A Cost Analysis of the Administration's Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Work Participation Proposal, Center for Law and Social Policy, April 10, 2002.

13. California Legislative Analyst's Office, President's Welfare Reform Reauthorization Plan — Fiscal Effect on California, April 15, 2002.

14. Several states have reserve funds from previous years that they could draw on to meet some of the initial increased costs. Those funds, however, are dwindling quickly. Many states do not have large enough reserves to maintain their current program level next year even without meeting additional requirements.

15. National Governors' Association and American Public Human Services Association, Welfare Reform Reauthorization: State Impact of Proposed Changes in Work Requirements, April 2002 Survey Results.