Tax Foundation Figures Result in Inaccurate Impressions of Middle Class Tax Burdens

by Iris J. Lav, Isaac Shapiro, Robert Greenstein, and James Sly

On April 15, 1999 the Tax Foundation issued a report stating that on average, Americans must work until early May to pay taxes. Each year since 1993, the Tax Foundation has claimed that the average tax burdens have reached a new record high, and that "Tax Freedom Day" occurs later in the year. The Tax Foundation is expected to release another tax burden report in the next few days.

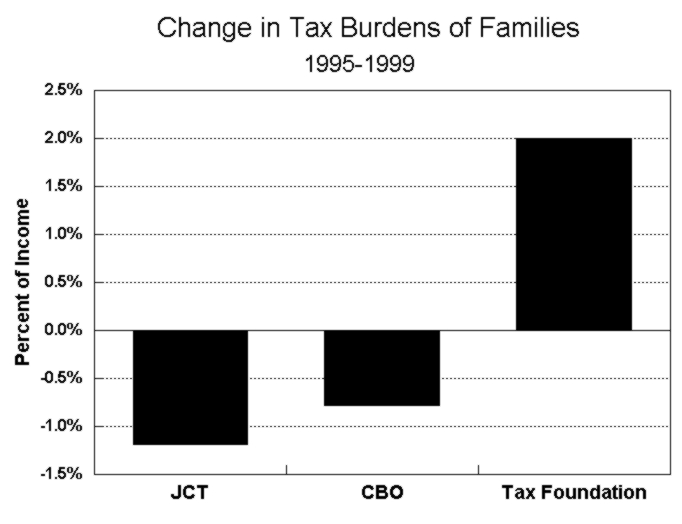

The Tax Foundation's report should be assessed in light of evidence from the two leading sources of tax information for Congress — the Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Committee on Taxation. These respected sources find that taxes on families in the middle of the income spectrum are substantially lower than the taxes the Tax Foundation claims Americans pay on average. Moreover, CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation find that taxes on middle-income families have been declining in recent years, not rising as Tax Foundation reports would lead the public to believe.

|

Joint Committee on Taxation data are changes in federal taxes for families with income between $30,000 and $40,000. The Congressional Budget Office data are for families in the middle quintile of the income distribution, with average income of $39,000 in 1999. The JCT and CBO data on federal taxes are combined with Commerce Department data on state and local taxes to estimate total taxes. State and local taxes from the National Income and Produce Accounts are taxes as a percent of Net National Product. Tax Foundation data are from "Tax Freedom Day" reports, which use taxes averaged over all taxpayers. |

Why is there this contradiction between the Tax Foundation and these two much more authoritative sources of tax data? It is because the picture the Tax Foundation presents — that the tax burden is high and has been rising — is inaccurate when applied to typical or average middle-class families. The Tax Foundation computes what it describes as the percentage of income that Americans, on average, pay in taxes and converts this to the portion of the year that Americans have to work to pay their tax bills. This methodology draws a misleading picture; it substantially exaggerates the amount of taxes that middle class families pay. (See box on page 3 for a discussion of the Tax Foundation's use of averages and terms such as "on average" and "average American.")

Under the methods the Tax Foundation uses, an increase in taxes solely on high-income taxpayers increases the taxes that the average taxpayer pays and thereby advances "Tax Freedom Day" to later in the year. This methodology can produce particularly sharp distortions when taxes are raised primarily on affluent taxpayers, as they were under the 1990 and 1993 deficit reduction laws, and when large increases in income from the stock market cause wealthy investors to pay more capital gains taxes.

The Tax Foundation's methodology errs in other important ways as well. Of particular concern, the Tax Foundation fails to count some of the income on which the taxes that it counts are levied. It counts capital gains tax payments as taxes but fails to count as income the capital gains income on which these taxes are levied. In addition, the Tax Foundation counts as taxes various items that clearly are not taxes, such as the optional premiums that elderly and disabled people elect to pay for physicians' coverage under Medicare. The methodological errors that the Tax Foundation commits all distort its figures in the same direction — they all make taxes look higher than they actually are.

In assessing the Foundation's report, the following points merit consideration.

1. The federal tax burden the Tax Foundation says families pay on average is about 28 percent larger than the federal tax burden that CBO estimates families in the middle of the income spectrum bear and about 51 percent larger than the federal tax burden the Joint Tax Committee estimates these families bear. In its 1999 Tax Freedom Day report, the Tax Foundation estimated that families on average pay 24.3 percent of their income in federal taxes, including income tax, payroll tax, and other taxes.(1) By contrast, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that families in the middle of the income scale pay 18.9 percent of income in federal taxes in 1999, while the Joint Committee on Taxation's estimate is 16.1 percent. The Tax Foundation's estimates are more than one-fourth to one-half higher than the estimates of these official institutions.

The federal tax burden posited by the Tax Foundation is not only higher than what CBO and the Joint Tax Committee estimate middle-income families pay but is also slightly higher than what CBO estimates that families in the next-to-the-top fifth of the population pay. CBO estimates that families in the next-to-the-top fifth will pay 22.2 percent of income in federal taxes in 1999. In its original 1999 report, the Tax Foundation claimed that Americans on average pay more than 24 percent. A recent revision by the Tax Foundation appears to place its estimate of the average federal tax burden in 1999 at approximately 22.5 percent.

|

Misleading Word-play? Both the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and a number of prominent economists such as William G. Gale of the Brookings Institution have criticized the Tax Foundation's methods as providing a misleading picture of the taxes that middle-class families pay. As noted elsewhere in this report, the average tax burden figure the Tax Foundation derives — and on which Tax Freedom Day is based — is substantially higher than the tax burden that families in the middle of the income scale pay. This is in part because the Tax Foundation's method effectively ascribes to middle-income families certain types of taxes and tax rates that apply primarily or solely to upper-income taxpayers. The Tax Foundation has responded to this criticism by tweaking the wording of its reports. In 1996, it described Tax Freedom Day as "...the day the average American can expect to quit working for Uncle Sam...." By 1999, the Tax Foundation was saying, "This is the day Americans on average will have earned enough...." and using phrases such as "...the tax burden borne by Americans..." (Emphasis added.) Despite this slight change in wording, many pundits and politicians misinterpret the Tax Foundation's reports to reflect how tax burdens have changed for a large portion of American families. The Tax Foundation material essentially invites this misinterpretation. When it says that Americans must work until May 3 or some such date to pay their taxes, the implication that most people would draw is that large numbers of Americans must work until that day to pay their tax bills, not just the well-off. Yet CBO data show that the tax burden of "Americans on average," as the Tax Foundation computes it, exceeds the tax burden not only of the middle fifth of the population but also of the next-to-the-top fifth. The Tax Foundation releases do not help readers understand that under our progressive tax system, "Americans on average" pay a substantially higher tax bill than a middle-income family does. |

2. The Tax Foundation's use of averages substantially exaggerates middle-class tax bills. In contending Americans must, on average, work until May to pay taxes, the Foundation computes average tax burdens. It takes what it says is the total amount paid in federal, state, and local taxes and simply divides this amount by the Foundation's estimate of the total amount of income in the nation. The result is the percentage of income the Tax Foundation pictures Americans as paying, on average, in taxes. The Foundation then converts this into the percentage of the year Americans must work to satisfy their tax obligations. There are fundamental problems with this approach.

The federal personal income tax is a progressive tax. The typical middle-income family is in the 15 percent federal income tax bracket. High-income families are in brackets with marginal rates more than twice that high and pay substantially higher percentages of income in federal income tax than middle-class families do. The tax burden figure the Tax Foundation computes by dividing total taxes by total income is misleading as an indication of the taxes that middle-class Americans pay. When applied to federal taxes, this tax figure significantly exceeds the percentage of income that both families in the middle of the income spectrum and families in the next-to-top fifth pay.

The problem of using the Tax Foundation's approach is easily seen. Suppose four families with $25,000 incomes each pay $1,250 in income tax — or five percent of their income — while one wealthy family with $500,000 in income pays $125,000 in income tax, or 25 percent of its income. Under the Tax Foundation approach, these five families pay 22 percent, on average, of their income in federal income taxes. (Total tax payments of $130,000 divided by total income of $600,000 equals 22 percent.)

But the 22 percent figure is misleading. The four moderate-income families pay five percent of their income in income tax, not 22 percent. Using averages in the manner the Tax Foundation does when talking about tax burdens produces skewed results; it essentially ascribes tax rates to the average person that only taxpayers at considerably higher income levels pay.

The Tax Foundation's averaging approach is flawed in the same regard with respect to various other types of taxes. For example, the Tax Foundation method assumes that middle-class families pay the same percentage of income in estate taxes as a family with a multi-million dollar income. But estate taxes are paid on only the largest one to two percent of estates; all smaller estates are exempt.

This holds true for corporate income taxes, as well, which most economists (including those at CBO) believe are primarily passed through to the owners of capital assets, and for capital gains taxes paid on the sale of stocks, bonds, and real estate. The Tax Foundation's averaging method effectively assumes that typical middle-class families pay the same percentage of income in corporate income and capital gains tax as wealthy investors and stockholders. That clearly is not correct.

3. Federal taxes have been declining for families in the middle of the income spectrum. The Treasury Department has calculated for each year going back several decades the federal income and payroll taxes paid by a married couple with two children that earns the median income. In 1999, this family paid a smaller percentage of its income in federal income taxes than in any year since 1965. Even when payroll taxes are added in, the family is found to have paid a smaller percentage of its income in federal income and payroll taxes in 1999 than in any year since 1978.(2)

The Tax Foundation itself acknowledged this point in a February 1998 release that received little coverage, where it acknowledged that "...federal taxes as a percent of income will be lower on the median single- and dual-income families in 1998 than two decades ago,...even without the 1997 Tax Relief Act."(3) In a more recent report released last month, the Tax Foundation stated that the tax burden on the median income two-earner family peaked in 1996 and has dropped since then.

Nor have taxes been rising at the state and local level. Commerce Department data show that state and local taxes amounted to 10.3 percent of Net National Product in 1999. This Commerce Department measure of state and local taxes has been remarkably stable over time; it was at about the same level in 1999 and throughout the 1990s as it was in 1977.(4)

4. The Tax Foundation's methodology misleadingly portrays the increase in federal revenue as a share of the economy in recent years as representing a rise in the average family's tax burden. The increase in revenue as a share of the economy largely reflects the increased taxes collected from high-income individuals as a result of substantial increases in their capital gains income and salaries and bonuses. It does not reflect an increase in ordinary families' tax burdens.

In 1998, former CBO director June O'Neill testified that tax receipts have risen in recent years as a share of the Gross Domestic Product "mainly because realizations of capital gains were unusually high and because a larger share of income was earned by people at the top of the income ladder, who are taxed at higher rates."(5) Sounding a similar note in testimony before Congress in January 1999, Lawrence Lindsey, an economist who served in the Reagan and Bush administrations and on the Board of Governors on the Federal Reserve System, stated: "A disproportionate share of this extra revenue is coming from upper income taxpayers through higher income tax payments. The likely reason for these payments is the booming stock market. The extra revenue is in part due to higher capital gains realizations due to higher stock prices, but is probably even more dependent upon higher bonuses being paid to upper bracket individuals."(6)

Federal Reserve Board Chair Alan Greenspan has made the same point. He testified in January 1999 that "...we have had a very significant rise in individual tax receipts which unquestionably are reflective of the very large capital gains; and secondarily, the impact of rising stock prices on other types of income."(7)

|

Tax Levels versus Expenditures on Food, Shelter and Housing Tax Foundation reports often state that families must pay more in taxes than they pay for food, clothing, and shelter combined. This Tax Foundation claim further illustrates the problems with using figures on total tax payments in the nation, total payments for food, and the like. If the statement that total tax payments exceed total expenditures for food, clothing and housing were accurate, that would tell us little about the relationship between taxes and spending for families in the middle of the income scale. It is no doubt true that upper-income families pay more in taxes than they do for basic necessities. At the same time, it also is true that low- and moderate-income families pay less in taxes than they spend for basic necessities; necessities consume most of their income. The precise family income level at which taxes typically exceed expenditures for food, clothing and housing is unclear. The Foundation's report does not help to answer that question. Furthermore, while Americans spend a smaller proportion of their incomes on food, clothing, and housing than they used to, this is not because they are paying more in taxes. Rather, it is because the share of after-tax expenditures devoted to food, shelter, and clothing has shrunk significantly, while the share devoted to costs for items such as health care has risen. In 1970, some 44 percent of after-tax expenditures went for food, clothing and shelter. That figure has declined to about 34 percent in 1999. A drop in the share of expenditures going for food accounts for most of the decline. |

A more formal analysis of the increase in taxes as a percentage of GDP was published by the Congressional Budget Office in January 2000. It found that between 1994 and 1998, capital gains realizations nearly tripled. The increase in capital gains taxes alone accounted for nearly one-third of the increase in tax collections relative to GDP. CBO also reported that a large share of the remaining increase could be attributed to the growth of other types of income that are concentrated at the top of the income distribution.(8)

These developments have little if any effect on families in the middle of the income scale. Nevertheless, the mistaken notion that the tax burdens of middle-class families have risen is the conclusion that most policymakers and pundits who cite the Tax Foundation's work draw from the Tax Foundation reports. The Tax Foundation's "Tax Freedom Day" methodology invites this misinterpretation by treating some of the increased taxes that high-income taxpayers pay as though those taxes were paid by the average taxpayer. This makes it appear as though middle-class families have to work longer to pay their taxes than they actually do.

5. The Tax Foundation's methodology contains other shortcomings that make taxes look larger as a percentage of income than they are. The Tax Foundation counts as taxes items that are not taxes. These include: optional Medicare premiums that older Americans pay if they wish to receive coverage for physician's services under Medicare; intra-governmental transfers that are solely bookkeeping devices and not taxes; and rental payments that individuals or businesses pay to state or local governments to rent property those governments own.

Furthermore, the Tax Foundation methodology fails to count all income. The methodology counts capital gains taxes as part of the taxes people pay, but it fails to count as part of people's income the capital gains income on which these taxes are levied. Counting taxes while failing to count the income on which the taxes are paid makes taxes appear larger as a percentage of income than they actually are. In addition, in a period such as the present when capital gains income — and hence taxes on such income — have risen rapidly, the Tax Foundation procedure makes even average tax burdens appear to have grown faster than is the case.

6. Federal individual income taxes represent a small portion of the total tax burden. The Tax Foundation numbers frequently are used by those who argue either that the federal income tax code should be replaced with a flat tax or consumption tax or that large income tax cuts should be the nation's top budget priority. The argument is that federal income tax burdens on middle-class families have exploded and reached crushing levels. The Tax Foundation's release of its study around April 15, the income tax filing date, may lead people to think federal income taxes are the main cause of the high tax burdens that the Tax Foundation pictures the average family as facing.

In fact, the CBO data indicate that families in the middle of the income spectrum paid just 5.4 percent of income in federal individual income tax in 1999. In the Tax Foundation's terms, that means it took only until January 20 for middle-class families to pay their federal income taxes. Congressional Budget Office analyses show that three of every four families are paying less than 10 percent of their incomes in federal individual income taxes.

End Notes:

1. On April 6, 2000, the Tax Foundation changed its estimate of the average tax burden for 1999 and preceding years, using recently revised data from the National Income and Product Accounts. The Tax Foundation did not specifically report a revised estimate of the federal tax burden, but the revised figure for the federal tax burden that is consistent with the Tax Foundation's revision of its estimate of the overall tax burden can be estimated by using the Tax Foundation's methodology with the updated NIPA data. Based on this methodology, the Tax Foundation's revised estimate of the average federal tax burden in 1999 is approximately 22.5 percent of income.

2. Department of the Treasury, Office of Tax Analysis, Average and Marginal Federal Income, Social Security and Medicare, and Combined Tax Rates for Four-Person Families at the Same Relative Positions in the Income Distribution, 1955-1999, January 15, 1998.

3. Tax Foundation, Family Tax Burdens 20 Years Later, Revisited, February 5, 1998.

4. This measure represents an average state and local tax rate for taxpayers of all income levels. Data are not available on the state and local tax burdens of typical middle-income families.

5. June E. O'Neill, The Economic and Budget Outlook: Fiscal Years 1999-2008, Testimony before the Senate Budget Committee, January 28, 1998.

6. Lawrence B. Lindsey, Federal Tax Policy, testimony before the Senate Budget Committee, January 20, 1999.

7. Testimony before the Senate Budget Committee, January 28, 1999.

8. Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic outlook: Fiscal Years 2001-2010, January 2000, pp. 52-56. CBO notes that most of the increase occurred before the cut in capital gains tax rates in 1997.