The Republican Budget Proposals

by Robert Greenstein

Summary

Table of Contents I. Does the Budget Lock Up Social Security Surpluses to Pay Down the Debt? II. Why These Long-Term Fiscal Concerns are Important III. Conclusion IV. Appendix Related Reports: |

The Senate and House Budget Committees this week approved budget resolution proposals that closely resemble each other. In addition, Republican Congressional leaders announced last week that they will seek enactment of a Social Security "lock-box" proposal; this proposal has since been unveiled by Senator Spencer Abraham.

In combination, the budget resolutions and the lock-box proposal are presented as preserving and protecting Social Security (and doing more for it than the Administration's proposals) and promoting fiscal responsibility, while still providing a substantial tax cut. Close examination reveals, however, that the budget plan and lock-box measure would not meet all of these goals and contain a number of surprising — and in some cases, disturbing — features.

Of particular note, these proposals could lead to very little debt reduction. Moreover, the large tax cuts the budget resolutions contain, in conjunction with a failure to ensure that meaningful debt reduction occurs, could lead to dangerously high deficits when the baby-boom generation retires.

Long-term budget forecasts indicate that under current law, budget surpluses will continue growing only through about 2012. After that point, the surpluses will gradually begin to recede. The tax cuts in the budget resolutions, however, would grow explosively in the latter years of the 10-year budget period that Congress uses (2000-2009) and keep growing in cost after that (unless some of the tax relief is canceled at that point). Thus, not only would the tax cuts consume most of the non-Social Security surplus over the next decade, but the tax cuts' cost almost certainly would be larger than the entire non-Social Security surplus at some point not long after 2009, throwing the non-Social Security budget back into deficit. Averting such an outcome would entail still-deeper cuts in programs in those years than the steep and unrealistic cuts the budget resolutions contain.

In addition, the lock-box proposal is constructed so Social Security surpluses can be used to finance individual retirement accounts rather than pay down debt. The lock-box proposal has evidently been designed in this manner to accommodate Social Security legislation that Republican leaders are now developing, which is expected to use the majority of the Social Security surpluses over the next decade for this private accounts. The projections of the Social Security actuaries show that the Social Security surpluses themselves will stop growing and start receding in the five years after 2009. Since the costs of the individual accounts in the legislation being developed would necessarily continue to mount in those years, there is substantial risk that this approach would result in costs for individual accounts that exceed the entire Social Security surplus and add further to re-emerging deficits — and begin to do so in the same years that the costs of the swelling tax cuts exceed the non-Social Security surplus.

The combination of tax cuts that ultimately exceed the non-Social Security surplus and individual accounts whose costs surpass the size of the Social Security surplus, along with the continuation of high interest payments on the debt (because little of the debt would have been paid down), would pose dangers for the nation, coming just as the baby boomers are beginning to retire in large numbers.

- The lock-box proposal would not ensure that the debt held by the public is reduced. The proposal would allow Social Security surpluses to be borrowed and used to establish a large new entitlement in the form of individual accounts, rather than being used to pay down the debt. Under the lock-box proposal, if Social Security surpluses are used to fund individual accounts rather than to pay down the debt, the debt limits are automatically adjusted upward.

- The Social Security plans now emerging in Republican leadership circles appear to envision using the bulk of the Social Security surpluses to fund individual accounts. The Social Security proposal that Reps. Bill Archer and Clay Shaw are developing, with the House leadership's blessing, as well as the plan Senator Phil Gramm has crafted, would establish individual accounts without reducing Social Security benefits. Such plans require large amounts of additional funding. These new funds could not come from the non-Social Security surplus, since the vast majority of that surplus would be used for tax cuts. This leaves only one source for funding these accounts — the Social Security surpluses.

- Under the emerging Republican approach, the Treasury would borrow the Social Security surpluses each year, provide bonds to the trust funds in return, and use the bulk of these surpluses to make deposits into individual accounts. (This is essentially the same type of mechanism that some Members of Congress have criticized as "double counting" when discussing the Administration's Social Security plan.) This is why the lock-box proposal provides for automatic increases in the debt limits if the Social Security surpluses are used to finance individual accounts. (1)

The Tax Cuts

While the bulk of the Social Security surpluses could be used to fund individual accounts rather than reduce the debt, the vast bulk of the non-Social Security surpluses would go for large tax cuts. The tax reductions the budget resolutions contain would grow extremely rapidly in the latter part of the 10-year budget period.

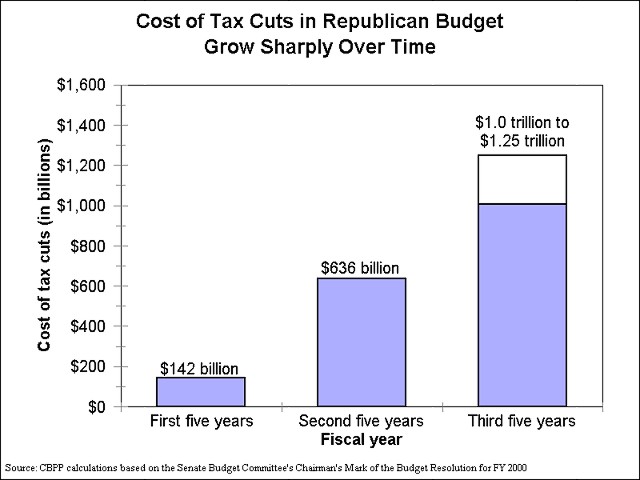

- The tax cuts would lose $142 billion in revenue in the first five years, but $636 billion in the second five years. In other words, they would cost 4 ½ times as much in the second five years as in the first five.

- The tax cuts would cost approximately $50 billion in 2004, more than $100 billion by 2006, slightly over $150 billion in 2008, and $177 billion in 2009. Tax cuts with costs that grow this explosively would necessarily continue growing in cost after the 10-year budget window ends.

Within a few years after 2009, the tax cuts reflected in the budget resolution would become sufficiently large that they would exceed the entire non-Social Security surplus projected for those years. Even if the tax cuts grew only in tandem with the economy (i.e., at the same rate as the Gross Domestic Product) in the years after 2009 — which would be unlikely since the tax cuts are slated to grow at several times the rate of GDP growth in the years through 2009 — they still would cost more than $1 trillion in the five years from 2010 to 2014 and would exceed the size of the non-Social Security surplus within a few years. With the tax cuts continuing to grow while the surplus ceased to grow and began to recede, deficits in the non-Social Security budget would re-emerge.

Indeed, CBO's long-term forecast shows that if none of the budget surpluses are used for tax cuts or program expansions, with all of the surpluses being devoted to paying down the debt, deficits in the unified budget will return some time between 2020 and 2030. By using most of the non-Social Security surplus for burgeoning tax cuts and paving the way to use much of the Social Security surplus for private retirement accounts — rather than for paying down debt — the budget plans would cause deficits to return much sooner, and climb substantially higher, than the CBO forecast projects.

These deficits would return sooner and climb higher not only because of the cost of the tax cuts and the individual accounts, themselves, but also because interest payments on the debt — now more than $200 billion a year — would remain high, since little of the debt would have been paid down. The opportunity to eliminate most or all of the publicly-held debt before the baby boom generation retires in large numbers would be foregone.

Cuts in Discretionary Programs

To help accommodate the tax cuts, the budgets the Senate and House Budget Committees have approved would require radical shrinkage of some parts of the federal government. Not only would the budget plans maintain the stringent caps the 1997 budget agreement placed on discretionary (i.e., non-entitlement) spending for years through 2002 — which themselves would require sizeable reductions in discretionary spending in the next several years — but the budgets call for large additional reductions in non-defense discretionary programs in the years after that.

- The Senate and House budget resolutions include approximately $200 billion in additional reductions in discretionary programs between 2003 and 2009, on top of the reductions that would result from enforcing the caps through 2002 and allowing discretionary spending to rise only with inflation after that. (The standard baselines that CBO and OMB use to project federal expenditures and budget surpluses over the next 10 years assume the discretionary caps will remain in place through 2002 and that discretionary spending will keep pace with inflation after that.) These additional reductions in discretionary programs provide room for the tax cuts in the budget resolutions to be larger than otherwise would be possible.

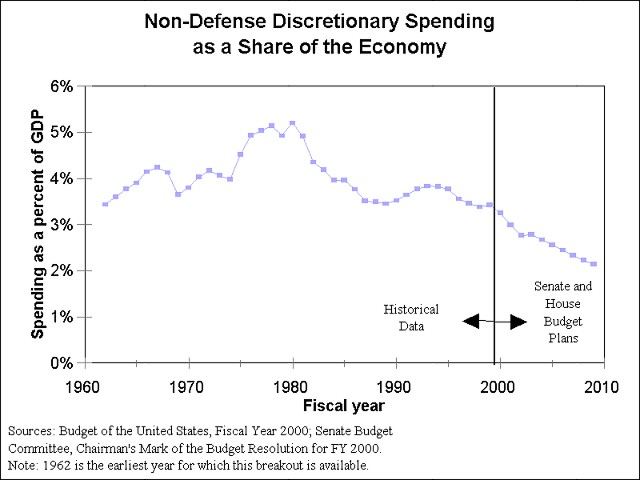

- The cuts the Senate Budget resolution contains in non-defense discretionary programs are so large that by 2009, overall non-defense discretionary spending would be 28 percent below its FY 1999 level, adjusted for inflation.(2) Under the House resolution, the reduction in non-defense discretionary programs would be 29 percent by 2009. These deep cuts would occur although non-defense discretionary spending already constitutes as small or smaller a share of the Gross Domestic Product than in any year since 1962.

- The Senate resolution emphasizes the Republican leadership's intention to protect or increase funding for large areas of non-defense discretionary spending, including highway and mass transit spending, crime programs, veterans health programs, elementary and secondary education, and research at the National Institutes of Health. Since total non-defense discretionary spending would fall 28 percent to 29 percent in purchasing power by 2009 while significant areas of the non-defense discretionary budget were shielded from cuts or increased, the remainder of the non-defense discretionary budget would have to be cut substantially more than 28 percent to 29 percent.

Reductions of this magnitude in discretionary programs seem unrealistic. If the tax cuts are enacted and the lock-box is in place, however, it could be difficult to escape such deep reductions. The tax cuts would cause most of the non-Social Security surpluses projected for the next 10 years to disappear. This means that if attempts were subsequently made to boost discretionary spending to higher levels, such efforts could be stymied by the lock-box. The lock-box effectively bars unbalanced budgets through 2009 in the non-Social Security part of the budget, and restoring some of the cuts the budget plans would make in discretionary programs could push the budget out of balance.

By consuming the non-Social Security surpluses, the tax cuts also would largely preclude use of any sizeable share of the surplus to help shore up Medicare (or to meet other unaddressed needs). Most analysts familiar with Medicare's daunting financing problems believe that a combination of substantial Medicare reforms and sizeable new resources will be necessary if long-term Medicare solvency is to be restored.

Other Risks Posed by the Lock-box Proposal

Adding to these concerns, the lock-box bill could make it harder for the federal government to manage the economy effectively and keep it out of recession. The bill sets limits on the allowable levels of debt held by the public; these limits assume the non-Social Security budget is in balance throughout the next 10 years. If the budget slipped out of balance, the Treasury would be barred from borrowing funds (from either the public or the Social Security trust funds) unless three-fifths of the Senate and a majority of the House so approved.

Under the lock-box bill, budget cuts or tax increases would be required when the economy weakened. This would be true because when the economy slows, expenditures rise and revenues decline (or grow more slowly). An economic slowdown consequently would cause the debt limits the lock-box bill sets to be exceeded, unless budget cuts or tax increases were enacted. Cutting government expenditures or raising taxes while the economy is faltering, however, is the reverse of what sound economy policy would prescribe. Doing so would risk pushing a weak economy into recession and making recessions deeper.

The lock-box proposal also poses other dangers. If a slowing economy threatened to cause the debt limits to be exceeded, but Congress and the President could not reach agreement in time on budget cuts or tax increases to avert that — and a three-fifths majority could not be amassed in the Senate to raise the debt limit — crisis would loom. The Treasury would have to default on government obligations or hold up government payments to beneficiaries and government contractors. Until now, it has taken a simply majority of Congress to raise the debt limit, and it often has proved hard to achieve a majority of that type. Securing a three-fifths vote in the Senate to raise the debt limit could prove excruciatingly difficult.

The proposal consequently would increase the potential of a government default and an interruption of vital government expenditures. CBO has warned that even a default lasting only a few days could have enduring consequences, because it could undermine confidence in the binding nature of the financial obligations of the U.S. Government and could raise government interest and contracting costs as a result.

These concerns do not suggest that a lock-box designed to prevent use of Social Security surpluses for other purposes is unwise. Rather, they indicate that any such lock-box legislation should be designed so that it does not risk precipitating a recession or a government default. These issues are discussed in more detail in a separate Center analysis, "The Lock-Box Proposal and the Economy."

Does the Budget Lock Up Social Security Surpluses to Pay Down the Debt?

The lock-box bill would write into law sharply declining limits on the publicly held debt. These limits would be set for the next 10 years and would track CBO's current projections of what the publicly held debt will be in that period if the non-Social Security budget is in balance and Social Security surpluses are used exclusively to pay down the debt.

These debt limits would be adjusted automatically in two circumstances. First, the debt limits would be reduced or raised to the extent that annual Social Security surpluses turned out to be larger or smaller than CBO had projected. Second, the debt limits would automatically be raised to the extent that Social Security reform legislation is enacted that uses some of the Social Security surpluses in a manner that makes these funds unavailable for paying down the debt, such as by funding individual accounts. (The debt limits would not be raised if Social Security surpluses were used to raise Social Security benefits.)

This second exception is of major importance. It is the reason that the proposal would enable Congress to bypass debt reduction and use the lion's share of the surpluses to fund individual accounts instead.

Republican leaders (especially in the House) have said that in coming weeks they plan to unveil a Social Security proposal to create government-funded private retirement accounts without cutting Social Security benefits. House Ways and Means Committee chair Bill Archer and Social Security Subcommittee chair Clay Shaw have indicated they plan to release such a proposal shortly. Senator Phil Gramm plans to introduce a somewhat similar proposal in the Senate. Both plans are based on the Social Security proposal that economist Martin Feldstein has fashioned.

The Feldstein plan entails the expenditure of trillions of dollars over the next several decades to create individual accounts without cutting Social Security benefits. The expenditure of these funds is necessary under the Feldstein plan because it is not possible to create individual accounts without cutting Social Security benefits unless large sums of new money are provided, at least for a number of decades. In an analysis issued last December, the Social Security actuaries estimated that the version of the Feldstein plan then in circulation would cost the government $6.4 trillion over the next 25 years.(3) (The latest version of the Feldstein plan would cost somewhat more than that, because its individual accounts are larger and more expensive than the accounts contained in the version of the plan the actuaries examined.(4))

From whence would these trillions of dollars come? They could not come from the non-Social Security surplus, since it would largely be consumed by tax cuts under the Republican budget resolution. There would be only one way to finance the large sums these individual accounts would require — by having the Treasury use most of the projected Social Security surpluses for the private accounts.

The Return of "Double-Counting"

Under what appears to be the plan the Republican leadership is developing, the Treasury would take the surplus Social Security revenues from the Social Security trust funds each year and give bonds to the trust funds in exchange. The Treasury then would use the borrowed money a second time. But instead of the principal "second use" of these funds being, as under the Clinton plan, to buy back Treasury bonds from the public and deposit them in the Social Security trust funds (thereby reducing the publicly held debt), the second use of most of these funds would be to establish private accounts. This is the reason the lock-box proposal calls for the ceiling on the publicly held debt to be increased automatically if Social Security reform legislation uses Social Security surpluses for purposes other than paying down debt.

This aspect of the Republican plan has significant budgetary implications. If the bulk of the Social Security surpluses are used for private accounts, little debt reduction will occur.

Tables in the documents accompanying the budget resolutions the Senate and House Budget Committees approved this week portray the debt held by the public as declining sharply under these budgets. These displays may prove to be misleading, however, as they assume the Social Security surpluses are used only to pay down debt. These displays do not reflect the impact of the soon-to-be-unveiled Social Security proposals that entail using the bulk of these surpluses for individual accounts instead. (It should be noted that the lock-box proposal would require all Social Security surpluses to be devoted to debt reduction if no agreement is reached on Social Security legislation.)

Why These Long-Term Fiscal Concerns are Important

CBO's long-term forecast shows that if all of the budget surpluses are used to pay down debt, with none of them used for program expansions or tax cuts, deficits will re-emerge in the unified budget between 2020 and 2030 and climb over succeeding decades to levels unprecedented for periods other than wars or recessions. CBO has cautioned that if most of the budget surpluses are used to expand programs and cut taxes rather than to pay down debt, deficits will return considerably earlier than this and climb even more rapidly.

The Republican budget framework entails using the vast majority of the non-Social Security surplus for tax cuts and contemplates using most of the Social Security surplus for individual accounts. Under such a scenario, little of the surplus would be used to reduce debt. Instead of the debt held by the public being eliminated by 2012 — as CBO forecasts will occur if all of the surpluses are used for debt repayment — and by about 2018 under the Clinton plan, the publicly held debt would remain large when the baby boomers begin retiring. We would have to continue spending a few hundred billion dollars a year on interest payments on the debt.

While continuing to have to make these interest payments, the government would have a smaller revenue base because of the tax cuts. As noted earlier, the tax cuts in the budget resolutions would themselves likely push the non-Social Security budget back into deficit before 2015. The tax cuts would cost $142 billion in the first five years and $636 billion in the second five years. If the cost of the tax cuts simply continued to grow after 2009 by the same average dollar amount as it would grow from 2003 to 2009, the cost of the tax cuts for the five years from 2010 through 2014 would be $1.25 trillion. Even if the growth in the cost of the tax cuts somehow could be held after 2009 to the rate of growth of the Gross Domestic Product, a feat that likely would entail taking back some of the tax cuts at that time, the revenue loss still would be exceed $1 trillion in the years from 2010 through 2014. (See Figure 1.)

Although the cost of the tax cuts would grow in the years after 2009, the non-Social Security surplus would not continue to enlarge. Long-term budget projections based on the CBO forecast indicate that the non-Social Security surplus will stop growing after about 2012 and begin to contract. As a result, the cost of the tax cuts would soon exceed the projected non-Social Security surplus, causing deficits to return in the non-Social Security budget.

The cost of the individual accounts expected to be included in the Republican Social Security proposals also would increase federal spending substantially in these years. The Feldstein plan, which apparently forms the model for the emerging Republican Social Security proposals, entails net expenditures of more than $300 billion a year by 2015, $400 billion a year by 2020, and $500 billion a year by 2025.(5) Under the Feldstein plan, the cost of the individual accounts would exceed the size of the Social Security surplus by sometime before 2015.

These added retirement-benefit costs would have to be shouldered despite the fact that the government already would face record deficits after the baby boomers retire, would have to make large interest payments on the debt (because little of the debt would have been paid down), and would be collecting less in revenue (because of the tax cuts). The net result would be deficits substantially larger than the deficits CBO forecasts for this period. Such deficits could be averted only by a fairly radical scaling back of the functions the federal government performs or by hefty tax increases. (Some may think that Social Security proposals involving individual accounts would ease these problems by adding to national saving and thereby promoting economic growth. The appendix at the conclusion of this paper explains why such proposals do not address the serious long-term fiscal problems identified here.)

Tax Devices Could Aggravate These Problems The budget plan could lead to the use of tax devices that enable the tax cuts in the next couple of years to be larger than would otherwise be possible. The budget resolution contains no net tax cut in 2000 and a net tax cut of only $7.4 billion in 2001. (The gross tax cuts would be about $15 billion in these years.) Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott and other Congressional leaders have spoken in recent weeks of designing certain tax cuts — such as capital gains cuts and expansions in IRA tax breaks for upper-income individuals — in such a manner that these tax cuts would raise revenue in their first few years. That could be accomplished by accelerating tax receipts into these years that otherwise would be collected in later years. The temporary increase in revenues would be used to finance larger tax cuts in the next few years than could otherwise be accommodated. Much of the revenue losses that such devices would cause in subsequent years would occur outside the 10-year budgeting period. This is another reason the cost of the tax cuts would likely keep growing significantly after the end of the 10-year budget period. |

Some critics of the Administration's proposals have criticized it for not making the hard choices on Social Security benefits and revenues needed to reduce the amounts by which Social Security benefit costs will exceed Social Security payroll tax revenues in future decades, and thus not doing enough to ease pressures on the rest of the budget at that time. The emerging Republican plan is a much more serious offender on these grounds. When the emerging Republican Social Security plans are taken into account, the Republican proposals would require the government to spend more on both retirement benefits for the elderly and interest payments on the debt than the amounts that would be expended under the Administration's plan, while collecting less in revenue to cover these costs.(6)

Does the Plan Do More for Social Security? A claim made in support of the proposals described here is that they would "do more for Social Security" than the Administration's proposals. For two reasons, this claim does not stand up. This claim stems from the fact that under the Clinton plan, the Treasury would continue for the next six years to use a modest portion of Social Security surpluses to help fund other government programs. Although the bulk of Social Security surpluses would go to pay down the debt held by the public during this period, an average of about $28 billion a year of these surpluses — or about $170 billion over the next six years — would be used to fund other government operations. The Republican lock-box bill would forbid this use of Social Security surpluses. This is the basis for the claim that the Republican plans would do more for Social Security than the Clinton proposals. This claim overlooks the fact, however, that the Republican lock-box proposal would not result in the trust funds having any more assets, while the Clinton proposal would not result in the trust funds having fewer assets. That under the Clinton plan an average of $28 billion a year of Social Security surpluses would be used to help fund other government programs does not mean the trust funds would have $28 billion a year less in Treasury bonds. When the Treasury borrows surplus revenues from the Social Security trust funds, as it does every year, it provides the trust funds with Treasury bonds in return. The trust funds receive the same amount of bonds regardless of whether Treasury then uses these surplus Social Security revenues to help fund other government programs or to pay down debt. Under the Administration's plan, an average of $28 billion a year would be used to help fund other programs rather than to pay down debt, but the trust fund balances would not be affected. To be sure, the fact that not as much debt would be paid down in the next few years because of the use of the $28 billion a year for other programs is not without consequences. But that is not a matter that would directly affect the assets or solvency of the Social Security trust funds. It also may be noted that this use of a portion of the Social Security surpluses to help fund other government operations would end after the sixth year, under the Clinton plan. In the years after that, the plan devotes sufficient amounts of the surpluses to debt reduction to make up for the effects on the accumulated debt of using some of the Social Security surpluses to fund other government operations during the first six years. The other reason that the claim that the Republican proposals would do more to bolster Social Security more is not correct is that it overlooks the fact that the Administration would shift $2.8 trillion dollars in additional assets into the Social Security trust funds over the next 15 years, above and beyond the assets the trust funds otherwise will hold as a result of the Social Security surpluses over this period. The Social Security actuaries project these additional assets would extend the year in which Social Security becomes insolvent by 23 years, from 2032 to 2055. By contrast, the Republican budget and lock-box proposals do not provide additional assets to the trust funds or extend the year in which Social Security would become insolvent. Under them, as under current law, Social Security would become insolvent in 2032. On the other hand, the Social Security reform legislation that Rep. Archer and other Republican leaders are developing may restore Social Security solvency for a longer period, such as for 75 years. |

Tax Cuts and Discretionary Programs

The large tax cuts would be accompanied by deep reductions in domestic non-entitlement programs. The budget plans retain the stringent caps that the 1997 budget agreement placed on overall expenditures for discretionary (i.e., non-entitlement) programs, a category of the budget that includes both defense and domestic programs. The caps require substantial reductions in overall discretionary spending in the next few years.

The budget resolutions also call for increases in defense spending. To boost defense spending while keeping overall discretionary spending within the tight discretionary caps requires cutting domestic non-entitlement programs heavily between now and 2002. Under the House and Senate budget resolutions, expenditures for non-defense discretionary programs in fiscal year 2002 would be 18 percent — or $62 billion — below the 1999 level, as adjusted for inflation.(7) Because major areas of the non-defense discretionary budget could not — or would not — be reduced 18 percent, if they were reduced at all, the remaining parts of the non-defense discretionary budget would have to be cut more sharply than that.

After 2002, the cuts in non-defense discretionary programs would deepen further. Overall funding for non-defense discretionary programs would rise modestly between 2002 and 2004 but then be frozen for five consecutive years, falling in purchasing power due to the effects of inflation. By 2009, non-defense discretionary spending under the Senate budget resolution would be 28 percent below the fiscal year 1999 levels, adjusted for inflation. The reduction would be 29 percent under the House resolution.

The budget plans call for certain favored areas of non-defense discretionary spending — including highways, mass transit, elementary and secondary education, crime programs, veterans health programs, and NIH research — to be protected and, in some cases, increased. As a result, by 2009, the rest of the non-defense budget would apparently have to be cut 35 percent to 40 percent below the FY 1999 levels, as adjusted for inflation.(8) These deep cuts would occur even though non-defense discretionary spending already comprises as small or smaller a share of the economy than at any point in nearly four decades. (See Figure 2.)

The nation faces budget decisions of unusual importance this year. While the budget decisions made in a normal year usually have significant effects for one or several years, the decisions made this year could have large consequences for decades.

The emerging Republican budget and Social Security proposals risk exacerbating the serious fiscal problems the nation faces when the baby-boom generation retires. These proposals would squander a historic opportunity to reduce sharply or eliminate the debt held by the public, with the result that we could be burdened with obligations to continue making large interest payments on the debt far into the next century. These proposals also would establish what would effectively be a large new entitlement for retirees in the form of individual accounts, while shrinking the federal revenue base.

In addition, the budget proposals would require cuts of stunning depth in non-defense discretionary programs. Due to the magnitude of these cuts, some programs that constitute public investments and hold promise of improving productivity — and hence economic growth — could face the knife, as could many programs to aid the most vulnerable members of society.

The course these proposals chart is a troubling one. It constitutes a high-risk undertaking that is not consistent with building a sounder fiscal structure in preparation for the budgetary storms that lie ahead. It also would be likely to lead over time to some radical changes in the role and functions of the federal government.

Would these Proposals Boost National Saving?

An argument may be made that deposits into individual accounts enacted as part of Social Security reform legislation would add to national saving and consequently lead to a bigger economy, thereby yielding more revenue for the government and alleviating the long-term fiscal problems this paper discusses. Increased saving should aid economic growth, and a bigger economy would result in more tax revenue than a smaller one. But claims that this growth would make the budget numbers add up over the long term and address the fiscal problems discussed here would be unfounded.

- The CBO baseline assumes that all of the projected surpluses are saved, including the surpluses in both the Social Security and the non-Social Security budgets. By contrast, all current budget proposals — including both Democratic and Republican proposals — would expend part of the surplus (either through tax cuts or through programs). As a result, all of these proposals would result in less saving than is assumed under the CBO baseline.

- Since the Republican budget plans would lead to less saving than the CBO baseline assumes, one cannot say these plans will somehow generate saving that will keep them from exacerbating the long-term fiscal problems that the CBO baseline already reflects. The CBO baseline forecast shows deficits returning sometime after 2020 and climbing to record levels. The budget proposals before Congress would make these problems more severe. (The Republican plan — and the Clinton plan as well — would add to saving and growth only when compared to a different sort of baseline which assumes that all of the surpluses would be spent if no action is taken to prevent that. Under such an alternative baseline, the long-term budget forecast would be more dire. Doing modestly better than such a baseline still could lead eventually to fiscal crisis.)

Moreover, the Republican plan would result in significantly less saving than the Administration's plan. Under the Administration plan, about three-quarters of the unified budget surpluses projected over the next 15 years would be transferred to Social Security and Medicare and saved. (All of these transferred funds would be saved, since none of them would be needed to pay current Social Security and Medicare benefits.) In addition, most of the funds placed in the USA accounts the Administration has proposed would represent additions to national saving, since these funds generally could not be withdrawn and spent until an individual retired. Overall, more than 80 percent of the unified budget surplus would be saved under the Clinton plan, rather than used for current consumption. (Not all of the funds deposited in USAs would represent new saving. Some individuals would feel they could place fewer resources in other saving vehicles since they would have USA accounts.)

Under the Republican plan, the bulk of the non-Social Security surplus would be used for tax cuts that boost current consumption, rather than for saving. Surplus funds that under the Clinton plan would be transferred to the Medicare trust fund or used for USA accounts, and hence largely saved, would instead be used for tax cuts and largely consumed. On the other hand, most of the funds placed in Social Security-related individual accounts under the Republican Social Security proposals now being developed would represent new saving, although as with USA accounts, not all of the funds placed in such accounts would constitute new saving. Some individuals would respond to the creation of the individual accounts by saving less elsewhere. Hence, under the Republican proposals, most of the Social Security surpluses (which constitute about 60 percent of total surpluses over the next 15 years) would be saved, but most of the non-Social Security surpluses would not be.

End Notes

1. This evidently also is the reason that the House budget resolution automatically raises the spending allocations given to the House Ways and Means Committee if that Committee uses the Social Security surpluses for individual accounts or similar purposes.

2. The FY 1999 level used here as a point of reference excludes emergency spending. If emergency spending were included, the dimensions of the discretionary cuts in the budget resolution would seem deeper.

3. Stephen C. Goss, Deputy Chief Actuary, Social Security Administration, "Long-Range OASDI Financial Effects of Clawback Proposal for Privatized Individual Accounts," December 3, 1998.

4. The plan the actuaries examined required the government to deposit an amount equal to two percent of a worker's wages into the worker's account each year. The new version of the Feldstein plan requires the government to deposit 2.3 percent of wages — 15 percent more — into a worker's account.

5. These figures are based on estimates by the Social Security actuaries. They include debt service costs.

6. Under the Feldstein plan, the Social Security benefit structure would remain intact. The plan entails that once retirees begin drawing income from their individual accounts, Social Security benefits would be reduced $3 for every $4 received from such an account.

The Social Security actuaries examined the Feldstein approach under several sets of assumptions. Under the most optimistic assumptions used, the actuaries projected that the plan would result in net increases in federal costs (over those that would be incurred if the current Social Security benefit structure is maintained intact) every year through 2051. Under less optimistic assumptions, the plan would increase government costs every year for the next 75 years.

7. The FY 1999 levels used here do not include emergency spending.

8. This calculation assumes the levels reflected for these favored program areas in the House and Senate budget resolutions for as many years as such levels are indicated. Where such levels are not provided through 2009, the calculation takes the level for the last year indicated and adjusts it for inflation for the remaining years through 2009.