REDUCING THE NUMBER OF UNINSURED CHILDREN:

Outreach and Enrollment Efforts

Testimony of Donna Cohen Ross

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

before the Senate Finance Committee

March 15, 2001

| View PDF version If you cannot access the file through the link, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

Chairman Grassley, Senator Baucus and members of the Finance Committee, thank you for the opportunity to speak to you today about the efforts states are making to reach out and enroll children in children's health coverage programs. My name is Donna Cohen Ross and I am the Director of Outreach at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The Center is a nonprofit policy institute here in Washington that specializes in programs and policies affecting low- and moderate-income families, including issues related to health coverage for the uninsured. Through our Outreach Division, the Center also works with states and local governments, health and human services providers, and community-based organizations and institutions on strategies to identify uninsured children who are eligible for publicly-funded health coverage programs and to help get them enrolled. The Center does not hold (and never has received) a grant or contract from any federal agency.

The enactment of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, the federal law that created the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), set in motion an unprecedented wave of activity to expand health coverage to uninsured, low-income children. Under the law, states can use their SCHIP allotments to expand Medicaid, to create a separate child health coverage program, or to do both. At this point, 95 percent of uninsured children in families with income below 200 percent of the federal poverty line (about $35,000 per year for a family of four in 2001) are now income-eligible for Medicaid or the SCHIP-funded separate program in their state.(1)

Making health coverage available is the first necessary step, but taking that step does not guarantee that children will enroll. To tackle this challenge, driven in part by the outreach requirements built into the SCHIP law, states have undertaken ambitious outreach initiatives. These activities have included widespread public education campaigns, efforts to simplify application forms and procedures, and efforts to provide application assistance at community-based sites, such as health clinics, schools, child care programs and other places that families with children gather. The federal government has been a critical partner in these endeavors, providing tools needed to design streamlined programs, resources to support outreach activities and technical assistance to help maximize opportunities to enroll children in health coverage.

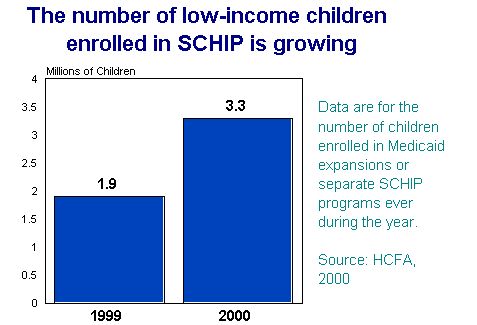

As a result of this multi-faceted approach, we now have over 20 million children covered under Medicaid and 3.3 million covered under SCHIP (Table 1), and recent Census data reveal that 1.1 million fewer children were uninsured in 1999 than in the previous year. These children — the vast majority of whom are in working families that previously had no access to affordable health coverage — now have access to health benefits that include routine check-ups and preventive care that children need to remain healthy and to achieve in school.

But the job is not yet done. Survey and focus group research has indicated that many families with eligible children may still be unaware that health coverage is available to working families, or they believe the enrollment process is difficult and time-consuming. Those who do initiate the process often find the forms confusing, the required documentation hard to collect and the process long and complicated. These problems may be compounded by language barriers or by perceptions about the program that are vestiges of Medicaid's former link to the welfare system.(2)

To ensure ongoing, lasting progress in reducing the number of uninsured children, states must continue to simplify and, where they have chosen to operate SCHIP-funded separate programs, apply the simplified procedures adopted for their SCHIP programs to Medicaid so that their children's health coverage programs will be well-coordinated. Sustainable improvements will depend on states' efforts to remove unnecessary barriers to enrollment, ensure children are smoothly transferred from Medicaid to separate SCHIP programs, or vice versa, if family income changes, and enable children to retain coverage for as long as they are eligible. Continued emphasis on aligning enrollment procedures in SCHIP-funded separate programs and Medicaid will save families from having to navigate the intricacies of two distinct systems and will help make further headway in recasting Medicaid as a health coverage program, rather than an adjunct to the welfare system. Alignment has advantages for states as well, making administration easier for states with dual-program systems.

Most states have taken these goals seriously and have used the substantial flexibility available to them under current law to take the following steps in both their SCHIP-funded separate programs and Medicaid. (3) (Table 2 and Table 3):

- Twenty-eight (28) of the 32 states that operate separate SCHIP programs use a single, joint application for Medicaid and the SCHIP-funded separate program;

- forty-two (42) states no longer consider a family's assets (such as savings or the value of a car) in determining eligibility for children's health coverage;

- forty (40) states have removed the requirement that families apply in person at a welfare office and allow applications to be submitted by mail;

- thirty-nine (39) states allow children to retain coverage for 12 months before they must renew their eligibility; and

- many states have taken steps to minimize the verification requirements, greatly reducing the paperwork burden on families and on caseworkers administering the program.

States have been a little slower to adopt two new options that can simplify the application process even further. But as some states pioneer these new options and share their positive experiences, other states are likely to follow suit. Thus far:

- Thirteen (13) states have adopted 12- month continuous eligibility, which allows children to retain coverage for a full year regardless of fluctuations in family circumstances, and

- eight (8) states have adopted presumptive eligibility, under which Medicaid providers and community entities such as child care agencies, WIC agencies, Head Start programs and others can directly enroll children who appear to qualify for coverage. Once enrolled, children can get the medical attention they need right away, while their families are allowed more time to complete necessary paperwork. Last year Congress granted states additional flexibility in administering this option, for example, additional entities such as schools and other agencies now can be authorized to conduct presumptive eligibility determinations. Several more states are now considering putting this option into practice.

When applications are easy to complete and submit, community-based organizations and institutions can play a more integral role in assisting families with enrollment. Families can get help from someone they know and trust in settings where they feel most comfortable — such as their child's school, child care center, health care provider and even through telephone "helplines" that offer rigorous follow-up assistance. These are all strategies families say would make it more likely for them to enroll, and in many communities such techniques are working.(4) For example:

- In the Albuquerque Public Schools, a team of school nurses uses information from the School Lunch Program to identify students who are eligible for health coverage. They can enroll these students into the state's Medicaid expansion program using the presumptive eligibility option.

- In Iowa, public health nurses serve as "child care health consultants" able to assist child care providers in keeping the child care center environment safe and healthy. As part of routine center visits, nurses provide information to child care workers about the state's children's health coverage programs and how to apply. They often help the child care provider sign up her own children, putting the provider in a better position — because of her personal experience — to assist the families of children in her care.

- In Florida, when families apply for federal child care assistance at community-based child care resource and referral agencies, the information they provide is electronically transferred onto a joint Medicaid/SCHIP application. Families answer a few supplemental questions needed to determine eligibility for health coverage and the application is printed out from the computer for the family to sign and mail to the child health insurance agency in a pre-addressed, postage-paid envelope.

- Hamilton County, Ohio runs a consumer "Helpline" that works with schools and community organizations to identify children who are likely to qualify for coverage. Families can call the Helpline and get application assistance over the telephone. Operators conduct intensive follow-up with families to help them with any necessary paperwork and track applications through the county system to ensure an eligibility determination is made without delay.

While these efforts have been essential to bringing us where to we are today, more can be done. States need to continue to take steps to simplify their programs and ensure they apply innovative simplification techniques from their SCHIP-funded separate programs to Medicaid. In addition, states must pay as much attention to simplifying the eligibility renewal system as they have paid to simplifying initial enrollment. This is critical to ensuring that children retain coverage for as long as they are eligible, protecting our investment in outreach and shielding children from unnecessary breaks in essential medical treatment when the enrollment period is up. States are beginning to experiment with new ideas for streamlining renewal and should be encouraged to do so.

As child health coverage programs continue to evolve at the state level, there are additional steps Congress can take to advance efforts to enroll more eligible children.

- Support efforts to cover families — While enthusiastic outreach efforts aimed at enrolling children are critical, a growing body of evidence shows that providing family-based coverage appears to make a substantial difference. States have aggressively expanded eligibility for low-income children, but working parents are still likely to lack coverage. In most states parents qualify for Medicaid only if they have income far below the federal poverty line. In the typical state, a parent in a family of three loses Medicaid eligibility when her income surpasses 67 percent of the federal poverty line. A parent working full time at $7.00 per hour earns too much to qualify for Medicaid in 37 states.(5) New research finds that family-based Medicaid expansions that cover parents result in a significant increase in Medicaid participation among children who already are eligible.

States have some flexibility under current law to cover parents in working families, but so far only about one-third of states have done so. (Table 4) The states that have extended coverage to low-income working parents are generally more affluent states. A principal barrier deterring other states from pursuing this option appears to be fiscal.

There's a lesson to be learned from the SCHIP experience. States were permitted to expand Medicaid eligibility for children beyond the federal minimum eligibility limits long before SCHIP was established, but a number of states felt themselves able to do so only after SCHIP provided enhanced federal matching rates for such expansions. Today, with SCHIP in place, all states have expanded coverage for children, in most cases to at least 200 percent of the federal poverty line. Providing states an enhanced matching rate for family coverage would be likely to result in a much larger number of states adopting such coverage.

As states contemplate implementing family coverage they should use all the options at their disposal to ensure that the same steps they have taken to simplify application and enrollment procedures for children are adopted for family-based coverage, as well. Aligning such procedures will make it more feasible to design a single application that can be used for the whole family. Moreover, having different application procedures for parents and children could negate the simplification measures put in place for children. For example, requiring a face-to-face interview for a parent to get enrolled confounds the advantage of having removed this requirement for children when both parents and children are applying.

Congress could help enhance family-coverage initiatives by providing states the option to allow 12 months of continuous eligibility, an option now available in children's coverage programs, but not currently available for families. This would afford parents the same advantage of uninterrupted care their children get under this option, and it would preclude the need for parents to undergo a more burdensome process to maintain their own coverage than to maintain coverage for their children.

A particularly vulnerable group of families are those that are leaving cash assistance and entering the workforce. These families are eligible for up to 12 months of Transitional Medical Assistance (TMA), a component of Medicaid designed to prevent families that leave welfare for work from immediately losing their health care coverage. A shortcoming of TMA is that many families are not aware of their eligibility for it and do not realize they may need to take certain steps to secure it when leaving welfare. In addition, families must submit, and states must process, three months of information on earnings and child care costs in the fourth month of TMA coverage, again in the seventh month, and once more in the tenth month to maintain coverage during the second six months of TMA.

TMA comes up for reauthorization at the same time as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). As the General Accounting Office has recommended, in reauthorizing TMA, Congress should give states the option of guaranteeing a full year of transitional Medicaid coverage to eligible beneficiaries without imposing burdensome reporting requirements. In addition to simplifying TMA for both families and states, this would enable states to give families a clear and unambiguous message that they will get at least one year of Medicaid coverage if they leave welfare for work.

- Coordinate child health insurance enrollment with other public benefit programs — Recent data from the Urban Institute indicate that about three-quarters of all low-income uninsured children live in families that participate the National School Lunch Program, WIC, the Food Stamp Program or Unemployment Compensation.(6) Since children who participate in these programs are likely to qualify for Medicaid or an SCHIP-funded separate program, they are important vehicles for child health coverage outreach and enrollment. Last year, Congress gave child nutrition programs — such as the School Lunch Program — new flexibility to share data from free and reduced-price meal applications with Medicaid and separate SCHIP programs for the purpose of facilitating children's enrollment in health coverage. Partnerships composed of state child nutrition agencies, school districts, state or local child health insurance agencies and consumer groups have begun to explore ways to use the School Lunch Program to link students to health coverage. Efforts so far appear to be worthwhile, but labor intensive. Support is needed for helping states take full advantage of these new opportunities to streamline enrollment in child health coverage programs. For example, additional funding may be needed to design efficient systems to transfer data electronically and to coordinate enrollment procedures across programs. Congress should consider providing states enhanced administrative matching funds to develop such systems, in much the same way enhanced Medicaid administrative funding is available to design and develop computer systems related to claims processing.

The concerted efforts of the past few years to reach out and enroll uninsured children in health coverage constitute a dramatic shift for this country. As new programs were getting off the ground, the results may have been slow to take hold, but we now seem to be making progress. Support for activities to better coordinate health coverage programs with other public benefit programs and for shoring up renewal procedures will help put in place strong systems for enrolling more children and helping them stay enrolled. Expanding family coverage will also be critical to ensuring we do not miss out on an important opportunity to reduce the ranks of the uninsured.

Thank you very much for giving me this opportunity.

| No joint application for Medicaid and SCHIP | Face-to-face interview required | Asset test required | Frequent

redetermination (more than once a year) |

| Nevada North Dakota Texas Utah |

Alabama Georgia(7) New Mexico(8) New York(9) Tennessee Texas Utah West Virginia(10) Wisconsin Wyoming4 |

Arkansas(11)

Colorado Idaho Montana Nevada North Dakota Oregon Texas Utah5 |

Alaska Florida(12) Georgia Maine Minnesota(13) North Dakota Oklahoma Oregon Tennessee7 Texas Vermont Wyoming |

States in bold print have adopted simpler enrollment procedures (no face-to-face interview, no asset test, and 12-month redetermination periods) for their separate SCHIP programs but not for their Medicaid programs. |

|||

| 1. Matthew

Broaddus and Leighton Ku, Nearly 95

Percent of Low-Income Uninsured Children Now are Eligible for Medicaid or SCHIP,

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 2000. 2. Michael Perry, Susan Kannel, R. Burciaga Valdez and Christina Chang, Medicaid and Children: Overcoming Barriers to Enrollment, The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, January 2000. 3. Donna Cohen Ross and Laura Cox, Making it Simple: Medicaid for Children and CHIP Income Eligibility Guidelines and Enrollment Procedures, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities/The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 2000. 4. Michael Perry, Susan Kannel, R. Burciaga Valdez and Christina Chang, Medicaid and Children: Overcoming Barriers to Enrollment, The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, January 2000. 5. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Survey of State Officials on Section 1931 Eligibility Rules, Conducted in the Summer of 2000, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, forthcoming 2001. 6. Genevieve M. Kenney, Jennifer M. Haley and Frank Ullman, Most Uninsured Children Are in Families Served by Government Programs, The Urban Institute, December 1999. 7. In Georgia, a face-to-face interview is required when the separate Medicaid application is used, but it can be done outside the Medicaid office. Georgia anticipates eliminating the requirement effective February 2001. 8. In New Mexico, community-based Medicaid On-Site Application Assistance (MOSAA) providers can help families complete a somewhat shorter "MOSAA" application; such contact satisfies the interview requirement. 9. In New York, contact with a community-based "facilitator enroller" meets the face-to-face interview requirement. 10. In West Virginia, families using the joint application do not have to complete a face-to-face interview if the child appears to be Medicaid-eligible and the application is transferred for an eligibility determination. Wyoming plans to eliminate the face-to-face interview for Medicaid on April 1, 2001. 11. Arkansas expects to remove the asset test for "regular" Medicaid and implement this change in July 2001. Utah still counts assets in determining Medicaid eligibility for some "poverty level" children. 12. Florida provides 12 months of continuous eligibility to children under age 5 enrolled in Medicaid. Children age 5 and older enrolled in Medicaid and all children enrolled in Healthy Kids and MediKids are required to have their eligibility redetermined every 6 months. 13. In Minnesota and Tennessee, children who qualify under waiver programs can undergo eligibility redetermination every 12 months as opposed to every 6 months under "regular" Medicaid. |

|||

| State | Income Eligibility Threshold for Working Families as a Percent of the Federal Poverty Line /1 |

| California | 108% |

| Connecticut | 158% |

| District of Columbia | 200% |

| Delaware | 108% |

| Hawaii | 100% |

| Maine | 158% |

| Massachusetts | 133% |

| Minnesota | 275% |

| Missouri | 108% |

| Wisconsin | 200% |

| New York /2 | 150% |

| Ohio | 100% |

| Oregon | 100% |

| Rhode Island | 185% |

| Vermont | 158% |

| Washington | 200% |

| Wisconsin | 185% |

| /1. The income threshold presented

in this column is based on the rules that apply to a family of three. It takes into

account a state's earnings disregard policies, but not other disregards or deductions. /2. New York's expansion has been enacted into law, but has not yet been implemented. Source: Survey of state officials conducted by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Information current as of March, 2001. Note that children in many of these states can qualify for coverage at higher income thresholds than apply to families. |

|