ADMINISTRATION'S

PROPOSED DISCRETIONARY SPENDING CAPS

REPRESENT UNSOUND AND INEQUITABLE POLICY

By

Robert Greenstein and Richard Kogan

|

PDF of report

Related Report: |

|

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

The Administration’s budget proposes to establish caps for each of the next five years on funding levels for discretionary programs (i.e., programs that are non-entitlements). Each year’s cap would be set at the overall funding level that the Administration’s current budget proposes for discretionary programs in that year, including defense as well as domestic programs.

The proposed caps would be set at levels that would necessitate steep cuts in domestic discretionary programs, unless defense, homeland security, and international affairs programs were funded at levels well below those the Administration’s budget shows for those programs over the next five years. As explained below, the levels that Congress ultimately provides for defense and anti-terrorism programs in years after 2005 are more likely to exceed than to fall below the levels shown in the Administration’s current budget; the Administration’s current budget omits a range of “out-year” defense and anti-terrorism costs that are likely to be funded.

- The Congressional Budget Office’s analysis of the President’s budget shows that under the budget, overall funding for domestic discretionary programs outside homeland security would be cut a total of $141 billion over the next five years.[1] This is the amount by which these programs would have to be cut under the proposed caps, unless defense, homeland security, and international affairs were funded at levels below those reflected in the budget. (Note: These cuts reflect the amounts by which the funding levels in the President’s budget fall below the CBO baseline; the baseline is CBO’s estimate of the amounts needed to maintain current levels of service in these programs. The baseline levels generally equal fiscal year 2004 funding levels, adjusted for inflation.)

- The cuts in domestic discretionary programs would grow larger with each passing year, reaching $45.4 billion in 2009. By 2009, expenditures for domestic discretionary programs outside homeland security would fall to their lowest level, measured as a share of the economy, since 1963.

These figures may underestimate the depth of the cuts in domestic discretionary programs that would occur under the proposed caps. Each year’s cap would apply to total discretionary funding for that year, including funding for defense and anti-terrorism programs. A major CBO analysis indicates that the defense-funding levels for future years that are reflected in the Administration’s budget significantly understate the costs in those years of the Administration’s own multi-year defense plan. In addition, the Administration’s budget contains no funds for the international war on terrorism after September 30.

This suggests that the amounts that the Administration actually requests for defense and anti-terrorism activities in years after 2005, when it submits its budgets for those years, may be considerably larger than the amounts shown for those years in the Administration’s current budget. If the proposed caps are enacted and defense and anti-terrorism activities are funded at higher levels after 2005 than the levels the current budget shows, the reductions in domestic discretionary programs would have to be even deeper than the amounts cited here. Under the caps, each additional dollar provided for defense and anti-terrorism programs would necessitate an additional dollar in cuts in non-defense programs.

The cuts that the proposed caps would require stand out not only because of their depth but also because they depart sharply from the experience with discretionary caps in the 1990s, when such caps proved effective for the better part of a decade. The caps in effect through most of the 1990s were part of larger, carefully balanced deficit-reduction packages. Both in 1990 when discretionary caps were first established and in 1993 when they were extended, discretionary caps were instituted as part of deficit-reduction measures that combined restraint on discretionary programs with increases in taxes (particularly for those who could best afford to pay more) and reductions in entitlement spending (in part by reducing Medicare payments to health care providers). The discretionary caps of the 1990s also were accompanied by “pay as you go” rules that required both entitlement expansions and tax cuts to be offset fully. In short, the discretionary spending caps of the 1990s were part of a larger program of shared sacrifice that was spread across the population and that played an important role in eliminating the large deficits of that era.

The current discretionary-cap proposal is very different. The new caps that the Administration is proposing would single out domestic discretionary programs for hefty cuts, without producing any overall deficit reduction. Both OMB and CBO estimates show that, taken as a whole, the proposals in the Administration’s budget would make deficits larger than they otherwise would be. This is the case because the proposed tax cuts would cost more than the cuts in discretionary and other programs would save. As a result, the stiff cuts in domestic discretionary programs which the proposed caps would lock in would be used not to reduce the deficit, but to finance a modest share of the cost of the tax cuts.

This analysis finds that the proposed caps on discretionary caps would be inequitable. It also finds the proposed caps would likely do more to hinder fiscal discipline than to advance it. The proposed caps have at least five basic flaws that make them ill-advised.

1. The cuts they would require would be too deep. The Administration’s budget includes funding levels through 2009 for each discretionary program account. The Administration’s proposal calls for the cap for each year to be set at a level equal to the total of the levels shown for that year for all discretionary program amounts.

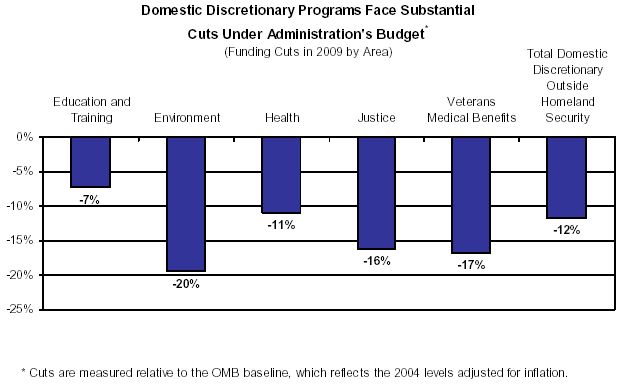

The program funding levels included in the budget thus provide a good indication of the depth of the cuts that would be entailed. These cuts are quite substantial (see chart). For example under the budget, environmental and national resource programs would be cut 20 percent by 2009 (that is, funding for these programs in 2009 would be 20 percent below the OMB baseline, which equals the 2004 funding level, adjusted for inflation). Veterans health benefits would be cut 17 percent. Among low-income programs, the number of low-income children and pregnant women at nutritional risk who participate in the acclaimed WIC nutrition program would be cut by 450,000 by 2009. The cuts would be particularly severe in the Section 8 housing voucher program.[2]

Under the budget, virtually every domestic discretionary program area would be cut over the next five years, except for space exploration. Even programs such as research at the National Institutes of Health and special education for children with disabilities — programs that the Administration has praised as being successful and is touting as programs it is proposing to increase in 2005 — would be cut in 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2009.

2. These cuts are not part of a balanced package; they do not contribute to deficit reduction but rather would be used to help finance tax cuts. The domestic discretionary cuts that would be required under the proposed caps would be seven times deeper (measured as a share of the economy) than the domestic discretionary program cuts instituted under the discretionary caps enacted in 1990 and 1993. Moreover, the 1990 and 1993 budget packages substantially reduced budget deficits, while the current Administration budget would increase them.[3]

As noted, the discretionary spending restraints enacted in the early 1990s were part of broader deficit-reduction efforts that entailed shared sacrifice. Members of Congress who favored increased discretionary spending, Members who sought entitlement expansions, and Members who wanted tax cuts had to agree to forgo their favored proposals in return for restraint on all parts of the budget.

The current discretionary cap proposal is being offered in a wholly different context. Not only would there be no restraint on the revenue side of the budget, but major new tax cuts are proposed on top of those enacted in 2001, 2002, and 2003. Moreover, based on analysis the Urban Institute-Brookings Tax Policy Center has conducted of the distribution of the tax cuts, the savings that would be achieved from the domestic discretionary program cuts that the budget contains — and the caps seek to lock in — would amount to less than the cost of the existing and proposed tax cuts for the one percent of the population with the highest incomes.

3. The proposed five-year discretionary caps would likely make it harder to secure agreement in coming years on a major deficit-reduction package. One lesson of the 1990s is that passing large-scale deficit-reduction measures entails putting all parts of the budget on the table and having various Congressional factions agree to accept deficit-reduction measures that affect their favored parts of the budget, in return for the application of such measures to other parts of the budget as well. To craft large-scale deficit reduction measures that can pass and be sustained, discretionary programs, entitlement programs, and taxes all need to contribute.

Yet the proposed five-year discretionary caps are so austere that further cuts in discretionary spending would be out of the question over the next five years. That would likely make it substantially more difficult to craft a major deficit-reduction package after the 2004 election, because there would be nothing left to give on the discretionary side to induce those who favor continued tax cuts to agree to stop cutting taxes and start restoring some of the revenue base.

For this reason, the proposed five-year discretionary caps could well set back the cause of deficit reduction, which badly needs a large, balanced, multi-year deficit reduction package that covers all parts of the budget. For reasons of both equity and fiscal responsibility, the proposed caps appear worse than no caps at all.

4.

It is not possible at the present time to set reasonable caps through

2009, because the Administration has not provided reliable budget figures

for defense and anti-terrorism costs in coming years. In an important

study released last summer and revised this February, CBO found that the

defense funding levels included in the Administration’s budget for the

“out-years” significantly understate the cost of the Administration’s own

basic defense plan, known as the “Future Year Defense Plan.” CBO also found

that the budget omitted costs of continuing the international war on

terrorism — costs that are expected to continue in the years ahead after our

withdrawal from

Based on the CBO analysis, estimates of the omitted defense costs total about $125 billion over the next five years. In addition, CBO has estimated the ongoing costs of anti-terrorism activities (exclusive of operations in Afghanistan and Iraq) as being in the range of $25 billion a year.

In the absence of reliable estimates from the Administration of defense and anti-terrorism costs (outside emergencies) over the next five years, it is impossible to know where to set multi-year caps.

5. History shows that unrealistically severe discretionary caps get blown away and may weaken fiscal discipline. In 1990 and 1993, discretionary caps that placed realistic restraints on discretionary programs were enacted. Those caps were honored.[4] In 1997, far more austere caps were enacted as part of the 1997 Balanced Budget Act, which sought to produce budget balance by 2002 under the budget assumptions in use at that time. These caps were so tight that Congress could not live with them, and they were blown away. The result was no meaningful restraint on discretionary spending.

The lesson is that reasonable caps negotiated as part of a balanced deficit-reduction package that contains shared sacrifice can be effective, but caps that are too severe are not sustained, especially when they are not part of a larger, balanced set of deficit-reduction policies. (Another factor that weakened Congress’ ability to adhere to the austere caps set in 1997, which would have required significant cuts in discretionary programs, was that Congress simultaneously began passing tax cuts that were not offset and that consequently violated the “Pay-As-You-Go” rules, which were part of federal law. If fiscal discipline is not enforced in other parts of the budget and deficit-increasing actions are taken in those areas, it is difficult to enforce rules that require cuts in discretionary programs.)

It should be noted that the caps the Administration is now proposing would entail cuts in domestic discretionary programs deeper than those called for under the unrealistic caps that were enacted in 1997 and could not be sustained.

Conclusion

The proposed caps would be inequitable; they would cut an array of basic programs deeply and essentially use the proceeds to help finance tax cuts. Moreover, the establishment of such caps this year would likely make it harder to craft a large bipartisan deficit-reduction measure in the future that seeks sacrifice from all parts of the budget.

The proposed caps represent unsound policy. Both from the standpoint of fiscal responsibility and from the standpoint of advancing the well-being of the American public in areas ranging from the environment to education to health and safety to aiding the less fortunate, the proposed caps would likely do more harm than good.

End Notes:

[1]

This figure is derived from CBO data supporting “Preliminary Results of

CBO’s Analysis of the President’s budgetary Proposals for Fiscal Year

2005,

[2] For a detailed analysis of the President's discretionary proposals, using OMB data, see "Administration's Budget Would Cut Heavily Into Many Areas of Domestic Discretionary Spending After 2005," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Revised March 5, 2004.

[3]

See Table 1 in Kogan, “Capping Appropriations: Administration’s Proposal

Regarding Discretionary Caps Likely to Prove Inequitable and

Ineffective,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities,

[4] The caps allowed emergency expenditures under circumscribed conditions. Through 1998, emergency funding was used only for the Gulf War and major natural disasters.