HEALTH COVERAGE FOR LEGAL IMMIGRANT CHILDREN:

New Census Data Highlight Importance of Restoring

Medicaid and SCHIP Coverage

by Leighton Ku and Shannon Blaney

| View PDF version If you cannot access the file through the link, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

When the Census Bureau released data in late September on the health insurance status of the U.S. population, attention appropriately focused on the welcome news that the number of people who lack health insurance fell by 1.7 million in 1999. Unfortunately, these Census data also contain news that is not so positive. These data show that the health insurance coverage of low-income children and parents in immigrant families has become more precarious since passage of the federal welfare law in 1996. This has occurred primarily as a result of a substantial decline in Medicaid coverage for these children and parents, which appears to have stemmed in significant part from restrictions that the welfare law placed on the eligibility of immigrants.

An analysis of the new Census data yields the following findings:

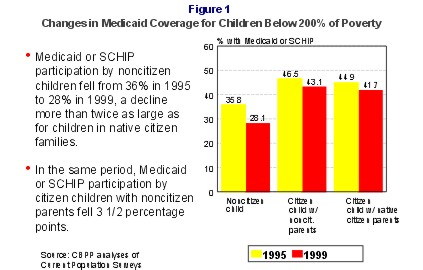

- The percentage of low-income immigrant children insured by Medicaid or the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), which was low before enactment of the 1996 legislation, has fallen substantially since then. A key reason that immigrant children in low-income families (defined as families with incomes below 200 percent of poverty, or $28,300 for a family of three) are at such high risk of being uninsured is that they are enrolled in publicly-funded coverage at much-lower rates than citizen children with native-born parents. Between 1995 and 1999, the proportion of low-income noncitizen children enrolled in Medicaid fell from 36 percent to 28 percent, an eight percentage point reduction.

- Low-income immigrant children were more than twice as likely to be uninsured in 1999 as citizen children with native-born parents. Some 46 percent of low-income noncitizen children were uninsured in 1999. In comparison, roughly one in five low-income citizen children with native-born parents — 20 percent — lacked coverage.

- Loss of publicly-funded coverage among immigrant children has substantially outstripped declines in coverage among citizen children with native-born parents. Between 1995 and 1999, the share of low-income citizen children with native-born parents enrolled in publicly-funded coverage (i.e., Medicaid, SCHIP, or state-funded programs) dropped by three percentage points, falling from 45 percent in 1995 to 42 percent in 1999. The eight percentage point drop over this period in the percentage of immigrant children from low-income families enrolled in publicly-funded coverage — from 36 percent to 28 percent — was more than twice as large.

- Citizen children in immigrant families lost publicly-funded coverage, and more of them became more uninsured. Citizen children of immigrant parents (most of whom are children born in the United States) are more likely to miss out on publicly-funded coverage, even though they remain eligible for it on the same terms as citizen children of native parents. Between 1995 and 1999, the percentage of low-income citizen children with noncitizen parents who receive Medicaid or SCHIP coverage declined from 47 percent to 43 percent. The proportion of citizen children in immigrant families who are uninsured grew from 28 percent to 31 percent during this period.

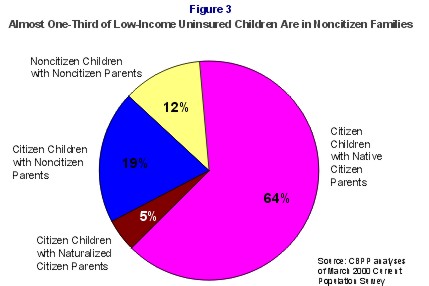

- Children in immigrant families — including both immigrant and citizen children in these families — account for nearly one-third of the low-income children in the United States who lack health insurance. The Census data show that in 1999, some 32 percent of all uninsured low-income children in the country were members of low-income noncitizen families. The difficulties in insuring children in immigrant families are limiting the effectiveness of efforts to reduce the numbers of low-income uninsured children in the United States.

- The low rates of the health insurance coverage of immigrant families could impede attempts to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in access to health care. A major public health goal is to eliminate the large gaps in health care access and health insurance status that exist across racial and ethnic groups. Because immigrants constitute a large proportion of the Hispanic and Asian populations in the United States, low rates of insurance among immigrants disproportionately affect these groups and contribute to racial and ethnic disparities. Some 58 percent of all low-income Hispanic children and 55 percent of low-income Asian children lived in noncitizen families in 1999. It will be difficult to reduce racial and ethnic gaps without policies that extend coverage to more people in legal immigrant families.

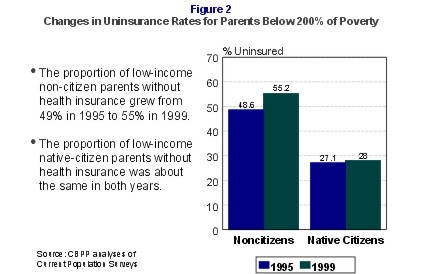

- Many legal immigrant women who are pregnant may be losing health insurance coverage. The Census data do not provide a ready way to identify which women were pregnant in 1999, but we can analyze trends in the insurance coverage of both noncitizen and citizen parents. Such analysis shows that the proportion of noncitizen parents who are uninsured is high and is rising. Between 1995 and 1999, the proportion of low-income noncitizen parents who were uninsured climbed from 49 percent to 55 percent. These noncitizen parents were more than twice as likely to be uninsured last year as their native-born counterparts. Immigrants have high levels of employment, but they tend to work in low-wage jobs that are less likely than other jobs to provide health insurance.

Like their children, immigrant parents experienced a sharp decrease in Medicaid coverage between 1995 and 1999. Over that period, the proportion of low-income noncitizen parents who have Medicaid coverage fell by almost one third — from 22 percent of these parents in 1995 to 15 percent in 1999.

There are no definitive data on health insurance coverage of low-income pregnant immigrant women, and the insurance rates of low-income immigrant parents are an imperfect proxy for them. If, however, these women have experienced the same kind of decline in insurance coverage as other low-income noncitizen parents — which is likely to be the case — then their health insurance status has deteriorated as well. A decline in coverage among low-income pregnant immigrant women would be especially troubling in light of the well-documented importance and cost-effectiveness of providing timely prenatal care to pregnant women.

Proposals to Restore Eligibility for Insurance

These new Census data come as Congress is considering legislation that would give states the flexibility to provide coverage through Medicaid and the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) to legal immigrant children and pregnant women who are barred from such coverage by the 1996 welfare law. At present, most legal immigrant children and pregnant women who entered the United States on or after August 22, 1996 (the date the welfare law was signed) are ineligible for health care coverage through Medicaid or SCHIP during their first five years here.(1) Even after they have resided in the United States for more than five years, legal immigrant children and pregnant women will face a series of complex and burdensome rules regarding the circumstances under which they can enroll in coverage, making it likely that relatively few will be able to take advantage of coverage until they become citizens. Several proposals before Congress seek to address this gap in coverage by according states the option of extending Medicaid and SCHIP eligibility to immigrant children and pregnant women lawfully residing in the United States on the same terms as their citizen counterparts.

Bills to provide states this option were introduced by Rep. Lincoln Diaz-Balart and 58 cosponsors in the House (H.R. 4707) and by the late Sen. John Chafee and 12 cosponsors in the Senate (S. 1227). Another piece of legislation introduced by Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Rep. Sander Levin (S. 792 and H.R. 1399) also includes this option. The option carries a modest cost — $500 million to $600 million over five years, according to Congressional Budget Office estimates. That amount is a small fraction of the amounts under consideration for other health care proposals, such as the $21 billion to $30 billion over five years that is being seriously considered for increased reimbursements to Medicare providers.

This proposal enjoys some bipartisan support. It has been included in the Administration's budget. The proposal also has been endorsed by Florida governor Jeb Bush, who has stated: "Lack of health care access is an obstacle to preventive treatments and timely care for acute conditions. We are all too familiar with the high costs associated with policies that only permit emergency treatment at critical points. Congressional approval of this bipartisan bill would offer an important alternative to current policy."(2)

In addition, on September 25, the House Commerce Committee approved Medicare "give back" legislation (H.R. 5291) that includes a provision according states the option to reduce the five-year bar on Medicaid and SCHIP eligibility for legal immigrant children and pregnant women who arrived in the United States on or after August 22, 1996 to a two-year bar. This legislation also would dispense with certain complex rules that are likely to reduce participation among these children and pregnant women after they reach the end of the period during which they are barred from coverage.

Despite the bipartisan support, it remains unclear whether any such provisions will be enacted in the short time remaining in the 106th Congress. Adding to the uncertainty, the Health Subcommittee of the House Ways and Means Committee on October 3 produced an alternative version of the Medicare "give back" bill that does not include any Medicaid or SCHIP provisions: Medicaid and SCHIP are not under the Ways and Means Committee's jurisdiction. The Senate has not yet taken action on the legislation.

The new Census data suggest that legislation to give states the option to restore Medicaid and SCHIP eligibility to legal immigrant children and pregnant women would be a modest but significant step to help shore up insurance coverage for one of the nation's most vulnerable groups. Such a measure also would move the nation one step closer toward assuring that all low-income children in the country have access to health insurance.

Background on Legal Immigrant Eligibility for Health Insurance

Historically, immigrants lawfully admitted as U.S. residents who were not yet citizens were accorded rights and responsibilities similar to those of native and naturalized citizens, except for the right to vote. Noncitizen immigrants pay taxes, and they must meet the civic responsibilities that citizens face, such as registering with the Selective Service System. In 1996, the federal welfare law and an immigration law enacted that year took steps to restrict the eligibility of noncitizen immigrants for public benefits such as Medicaid, food stamps and the Supplemental Security Income program (SSI). For example, most lawfully admitted immigrants were barred from Medicaid for their first five years in the country if they entered the United States on or after August 22, 1996.(3)

Following the impositions of these restrictions, some states began to provide health insurance for certain categories of legal immigrants ineligible for Medicaid or SCHIP. States that offer coverage to these immigrants receive no federal matching funds under Medicaid and SCHIP and must bear the full cost of providing the health insurance. At the current time, 13 states extend Medicaid coverage at their own expense to legal immigrant children who entered the country on or after August 22, 1996. (These states are California, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia and Washington.(4)) Ten states with separate child health insurance programs funded through SCHIP serve recent immigrant children in those programs (California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Texas).

In some of these states, coverage is limited. For example, Florida recently imposed a ceiling on the number of immigrant children it serves at state expense in its SCHIP program, placing additional children who apply on a waiting list.

In all of these states, one of the effects of the federal eligibility restrictions has been to shift costs from the federal government to the states. In states that have not elected to provide health insurance for these immigrants, many of the costs of providing care have been shifted to counties and localities that fund public hospitals and clinics. The magnitude of these cost shifts will grow over time, as the number of immigrants who arrived since August 1996 increases.

Declines in Participation Among Eligible Immigrants

Since 1996, the number of immigrants participating in Medicaid has declined markedly. There also has been a reduction in participation by citizen children in immigrant families. Although citizen children of immigrants remain eligible for assistance, many [some] immigrant families apparently have became confused about the eligibility rules or are afraid to participate because of a belief that their children's use of Medicaid might cause immigration problems for themselves.

An Urban Institute study of participation by immigrants in Los Angeles found that enrollment in Medicaid by both immigrant children and citizen children in immigrant families fell steeply after passage of the welfare law.(5) Similarly, analyses of Census data for the nation as a whole indicate that Medicaid participation declined between 1995 and 1997 for immigrant children as well as for U.S.-born children of immigrants and that the proportion of these children who lack any health insurance increased.(6) In addition, the General Accounting Office has reported that one-third of all low-income children who are eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled are children from immigrant families.(7)

One factor that may have exacerbated these developments is that it has often been difficult to encourage immigrants to participate, despite outreach initiatives. Immigrant eligibility is difficult to explain in simple terms. One child in an immigrant family may be eligible, while another child in the same family is not, based on the date of entry into the country. Restoring Medicaid and SCHIP eligibility for immigrant children and pregnant women who have entered the country since August 22, 1996 — so that the eligibility criteria for these children and women are the same as the criteria for other children and pregnant women — would simplify the program and make it easier to understand, administer, and promote through outreach efforts.

Because of the federal prohibitions related to immigration status, all Medicaid and SCHIP application forms must ask about the immigration status of applicant children. Even if a state offers full Medicaid or SCHIP eligibility to recent immigrants using state-only dollars, it must include such questions to determine whether expenses on behalf of each participant should receive federal matching funds. There is some evidence that such questions may intimidate some immigrant families and cause them to avoid completing an application.(8)

Simplifying eligibility could help children in non-immigrant families, as well. Many states are working to simplify their Medicaid and SCHIP applications for children to make the applications easier to complete and less daunting. The complex immigrant eligibility rules necessarily makes the application forms and process that all children must go through somewhat longer and more complicated than otherwise would be the case.

Recent Trends in Immigrants' Health Insurance Coverage

To examine immigrants' health insurance coverage and how it has changed over time, we analyzed the Census Bureau's Current Population Survey (CPS), the mostly commonly used survey for health insurance trends. We compared the just-released data on insurance coverage in 1999 to data on coverage in 1995, prior to enactment of the welfare law.(9) We focused on people living in families with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line.

As Figure 1 shows, low-income immigrant children had lower rates of Medicaid coverage in 1995 than the children of native citizens. This gap widened further by 1999, as the number of immigrant children with Medicaid coverage fell by 190,000 between 1995 and 1999.

In addition, the number of citizen children in immigrant families who receive Medicaid dropped by 280,000 between 1995 and 1999. The number of citizen children of native-born parents who receive Medicaid also declined between 1995 and 1999.(10)

In 1999, almost half of the children who were not citizens — 46 percent — were uninsured (see Table 1). Among citizen children in immigrant families, nearly one-third — 31 percent —lacked insurance.(11) By contrast, about one-fifth of citizen children of native parents — 20 percent — were uninsured.(12)

|

1995 |

1999 |

Change in percentage |

|

|

Noncitizen Children |

|||

|

Medicaid or SCHIP |

35.8% |

28.1% |

-7.7* |

|

Employer-Sponsored Insurance |

16.6% |

19.2% |

2.6 |

|

Other Private Insurance |

2.5% |

6.5% |

4.0* |

|

Other Public Insurance |

1.1% |

0.6% |

-0.5 |

|

Uninsured |

44.0% |

45.6% |

1.6 |

|

Total |

100.0% |

100.0% |

|

|

Citizen Children with Noncitizen Parents |

|||

|

Medicaid or SCHIP |

46.5% |

43.1% |

-3.5* |

|

Employer-Sponsored Insurance |

21.2% |

21.8% |

0.6 |

|

Other Private Insurance |

2.6% |

2.6% |

0.0 |

|

Other Public Insurance |

1.2% |

1.2% |

0.0 |

|

Uninsured |

28.5% |

31.3% |

2.8* |

|

Total |

100.0% |

100.0% |

|

|

Citizen Children with Native Citizen Parents |

|||

|

Medicaid or SCHIP |

44.9% |

41.7% |

-3.3* |

|

Employer-Sponsored Insurance |

26.0% |

29.2% |

3.2* |

|

Other Private Insurance |

7.7% |

7.9% |

0.2 |

|

Other Public Insurance |

1.9% |

1.6% |

-0.3 |

|

Uninsured |

19.5% |

19.5% |

0.1 |

|

Total |

100.0% |

100.0% |

|

|

* Difference is statistically significant with 95 percent or better confidence. |

|||

An important reason why the children of native citizens fare better than the children of immigrants is that they have higher rates of coverage through employer-sponsored health insurance. It also may be noted that while the rate of employer-based coverage increased significantly between 1995 and 1999 for the children of native citizens, there was no significant change in employer-based coverage for the children of immigrants. (The data show increases in employer-based coverage for the children of immigrants, but these increases were not statistically significant.)

Between 1998 and 1999, there were some positive changes in the insurance coverage of low-income children, including an increase in Medicaid participation among citizen children in low-income immigrant families and a reduction in the percentage of children in low-income native-citizen families who were not insured. Nevertheless, only a portion of the ground lost between 1995 and 1998 was regained. In addition, some of the data that indicate improvements between 1998 and 1999 are puzzling and may not be entirely valid.

For example, the percentage of low-income noncitizen children who are uninsured declined significantly between 1998 and 1999. This decline, however, was caused primarily by more than doubling the share of low-income immigrant children reported as having "other private insurance," from 2.5 percent of these children in 1998 to 6.6 percent in 1999. "Other private insurance" primarily includes non-group insurance purchased on an individual basis and insurance that nonresident parents purchase as part of child support agreements. It is hard to imagine why the rate of other private coverage should have more than doubled in a single year for low-income immigrant children, especially since there were no corresponding changes in such insurance coverage for other groups of children.(13) If, in fact, there was no actual change in other private coverage among low-income immigrant children (and no offsetting growth in other types of insurance), then the reduction between 1998 and 1999 in the percentage of low-income immigrant children who are uninsured would not have been statistically significant. Thus, while it appears that the percentage of low-income immigrant children who lack insurance declined between 1998 and 1999, it is possible these data are flawed.

The data also indicate that the percentage of low-income citizen children in immigrant families who have Medicaid or SCHIP coverage increased from 38 percent in 1998 to 43 percent in 1999. This increase was statistically significant, but it still left the proportion of such children with Medicaid or SCHIP coverage below the 1995 level, despite the creation of SCHIP in the interim. Various factors may have contributed to the improvement between 1998 and 1999. Medicaid and SCHIP outreach efforts aimed at minority children, as well as other efforts to assuage immigrant parents' fears about participation in these public programs, may have had some success in attracting more immigrant parents to enroll their children in these child health insurance programs.(14) In addition, the CPS data show there was a general increase in the Medicaid and SCHIP enrollment of low-income children in 1999 as states continued to implement and expand their child health insurance programs.

Ideally, we would have provided data about insurance trends for pregnant immigrant women. The CPS does not ask about pregnancy, however, rendering it infeasible to obtain direct estimates of insurance coverage for pregnant women. We instead analyzed coverage trends for immigrant parents, which are important in their own right and which also may serve as imperfect indicators of the insurance patterns of pregnant women.

The proportion of low-income noncitizen parents who lack health insurance was high in 1995 and still higher in 1999. Some 49 percent of low-income immigrant parents were uninsured in 1995, compared to 27 percent of low-income native-citizen parents. In 1999, the share of low-income native-citizen parents who are uninsured was about the same, 28 percent. But the share of low-income immigrant parents without insurance had climbed to 55 percent.

This increase in the proportion of low-income immigrant parents without insurance was due primarily to a substantial drop in Medicaid coverage among this group between 1995 and 1999. The proportion of low-income immigrant parents covered through Medicaid fell from 22 percent in 1995 to 15 percent in 1999, a decline of almost one-third. (See Table 2). Medicaid participation also fell among low-income native-citizen parents, but the decline among this group of parents was fully offset by an increase in employer-sponsored coverage.

|

1995 |

1999 |

Change in percentage points,1995-99 |

|

|

Noncitizen Parents |

|||

|

Medicaid |

21.7% |

15.3% |

-6.4* |

|

Employer-Sponsored Insurance |

26.2% |

26.0% |

-0.2 |

|

Other Private Insurance |

2.5% |

2.9% |

0.4 |

|

Other Public Insurance |

1.0% |

0.6% |

-0.4 |

|

Uninsured |

48.6% |

55.2% |

6.6* |

|

Total |

100.0% |

100.0% |

|

|

Native Citizen Parents |

|||

|

Medicaid |

27.3% |

21.7% |

-5.6* |

|

Employer-Sponsored Insurance |

36.9% |

41.9% |

5.0* |

|

Other Private Insurance |

5.3% |

5.3% |

0.1 |

|

Other Public Insurance |

3.4% |

3.0% |

-0.4 |

|

Uninsured |

27.1% |

28.0% |

0.9 |

|

Total |

100.0% |

100.0% |

|

|

* Difference is statistically significant with 95 percent or better confidence. |

|||

As Table 2 also indicates, the proportion of low-income immigrant parents with employer-based coverage is considerably lower than the proportion of low-income native-born parents with such coverage. This large difference is not primarily due to higher unemployment rates among immigrant parents; the unemployment rates of foreign-born and native citizens differed by less than one percentage point in 1999.(15) Much of this insurance gap appears due to the fact that a greater share of low-income immigrant parents are employed in low-wage jobs in the agricultural, food processing and service sectors that do not offer health insurance. While the proportion of low-income native-citizen parents with employer-based insurance rose between 1995 and 1999, no similar increase occurred among low-income immigrant parents.

Among immigrants and natives alike, parents are more likely to be uninsured than their children. Coverage needs to be strengthened among both groups of low-income parents. Between 1998 and 1999, there was some improvement in the health insurance coverage of children in immigrant families, but there was no equivalent gain for immigrant parents who also lost Medicaid eligibility because of the restrictions added in the 1996 law. The need to strengthen coverage is particularly acute among immigrant parents who work at low-wage jobs. These parents face particularly serious barriers in securing employer-based coverage.

Immigrants Constitute a Sizeable Share of the Uninsured Population

The lack of insurance coverage among millions of low-income children prompted lawmakers to expand Medicaid and create SCHIP. Yet efforts to enroll more children in these two health insurance programs will be impaired if enrollment by low-income children in immigrant families remains low. As seen in Figure 3, almost one-third (32 percent) of uninsured children in families with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line live in noncitizen families. A disproportionate share of the burden of being uninsured falls on the children of immigrants.

Some of these low-income children are barred from coverage solely because they are recent immigrants. The number of children barred from coverage for this reason will grow over time. Many more are citizen children in immigrant families who appear to be deterred by confusion about Medicaid and SCHIP eligibility rules regarding immigrants and by parents' fears that enrolling their children could adversely affect the parents' immigration status.

Immigrants Are Major Segments of Latino and Asian Communities

An important health goal for the nation has been to reduce the level of disparities in access to health care for racial and ethnic groups in the United States. The overall proportion of Latinos who lack insurance — 33 percent — is higher than the proportion for any other racial or ethnic group. The percentage of Asians who are uninsured — 21 percent — is almost double the

Among Asians, 55 percent of low-income children are members of noncitizen families. Some 48 percent of low-income Asian parents are not citizens.

It will be difficult to raise Latinos' and Asians' insurance levels substantially (and thereby improve their access to health care) without further efforts to improve coverage among immigrant families.

Immigrants' Access to Medical and Dental Care

The new Census data do not provide information about access to or use of health care services. Other recent research has confirmed, however, that immigrants have less access to medical and dental care than similar native citizens, in large measure because of their lack of insurance.

- An important indicator of access to care is whether people have a usual place where they can go for medical care, such as a doctor's office or clinic. One of the national policy objectives established by Healthy People 2000 (which sets forth the official public health objectives for the nation established by the Surgeon General) is that the proportion of Americans who lack a usual source of care be no greater than five percent. The proportion of people in immigrant families who lack a usual source of care is far larger than this, in part because so many members of immigrant families are uninsured. A study by UCLA researchers found that 46 percent of immigrant children — and 25 percent of U.S.-born children in immigrant families — have no usual place to get care. By contrast, 16 percent of children in native-citizen families have no usual place to get care.(16)

- An Urban Institute study found that almost two-fifths of immigrant children — 38 percent — were unable to see a doctor or nurse (even in an emergency room) in the preceding year. This rate is almost three times higher than the rate for the children of citizens. Immigrant adults and citizen children of immigrants also are less likely to see a doctor than members of native-citizen families.(17)

- The Urban Institute study also found that even after controlling for factors such as income, education, health status and state of residence, immigrants and their children are less likely to get primary care or dental care than members of native-citizen families. In addition, contrary to what many people assume, immigrants are less likely to receive care in emergency rooms than members of native-citizen families.(18)

- Finally, the Urban Institute study found access to health care services to be substantially greater among immigrants and children in immigrant families who have health insurance, including Medicaid, than among immigrants without insurance. Having insurance is strongly associated with improvements in access to health care. (Some insured immigrants nevertheless continue to have problems with access to care because of language problems or other nonfinancial barriers to care.)(19)

The Potential for Legislative Change

Congress is currently considering providing $21 billion to $30 billion over five years in higher Medicare payments to health care providers such as hospitals, nursing homes, and health maintenance organizations. The argument advanced for legislation that would provide these funds is that the Medicare provisions of the 1997 Balanced Budget Act, which were enacted as part of the effort to eliminate deficits and balance the budget, hit providers too hard and can be eased now that budget surpluses have emerged.

The restrictions on the eligibility of legal immigrants for programs such as Medicaid were enacted in 1996 largely for the same reason — to help erase deficits and balance the budget. The proposal to accord states the option of restoring Medicaid (and SCHIP) eligibility to legal immigrant children and pregnant women who entered the United States on or after August 22, 1996 would cost $500 to $600 million over five years, according to the Congressional Budget Office, a tiny fraction of the cost of the Medicare "give backs." If costly restorations affecting health-care providers are to be considered, it seem appropriate also to consider some modest restorations affecting highly vulnerable populations such as low-income immigrant children and pregnant women.

As discussed above, according states the option to provide health insurance coverage to newly arrived legal immigrant children would help states reach and enroll more of the low-income children who remain uninsured. Furthermore, states could simplify their child application and enrollment procedures if they could dispense with complex immigrant eligibility determinations. Outreach messages could be simplified, making it easier for community groups such as schools and churches to help enroll low-income children in immigrant families.

Enabling these low-income immigrant pregnant women and children to obtain Medicaid or SCHIP coverage also serves other purposes. It helps to ensure they can receive prenatal care, well-child care, immunizations and other preventive or primary care before they become sick and develop more serious health problems. It also provides some relief to safety-net providers. In many areas, public and nonprofit clinics and hospitals have had to absorb costs of providing care to uninsured children from immigrant families who are brought to these institutions when they become ill.

Conclusion

The insurance coverage of low-income children and parents in immigrant families grew more precarious between 1995 and 1999. The principal factor behind the increases in the percentages of these children and parents who are uninsured has been a substantial decline in Medicaid coverage for these children and parents, which has stemmed in significant part from the restrictions placed on immigrant eligibility in 1996. Pending legislation to grant states the option of extending Medicaid and SCHIP coverage to immigrant children and pregnant women who entered the country since the welfare law was signed would constitute an important step toward addressing this gap in the health insurance system and would help provide coverage to some of the nation's most vulnerable uninsured individuals.

End notes:

1. Recent immigrants are eligible for Medicaid-funded emergency medical services but cannot receive preventive and primary health care services, such as prenatal care for pregnant women or well-child care for children, under Medicaid or SCHIP. States may elect to offer non-emergency health insurance coverage to recent immigrants as add-ons to their Medicaid or SCHIP programs but must do so entirely with state funds, without federal matching dollars.

2. Letter of Gov. Jeb Bush to Sen. Bob Graham about S. 1227, dated May 11, 2000.

3. A few categories of immigrant are exempted from this ban, such as refugees and asylees. They may participate in Medicaid for their first seven years after entry into the United States. For more details, see Claudia Schlosberg, Immigrant Access to Health Benefits: A Resource Manual, Boston, MA: The Access Project, 2000 or Wendy Zimmermann and Karen Tumlin, Patchwork Policies: State Assistance for Immigrants Under Welfare Reform, Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 1999.

4. Most of these states also serve immigrant pregnant women. New York provides Medicaid prenatal services to pregnant immigrant women because of a federal court ruling in the case Lewis v. Grinker.

5. Wendy Zimmermann and Michael Fix , "Declining Immigrant Applications for Medi-Cal and Welfare Benefits in Los Angeles County," Urban Institute, July 1998.

6. E. Richard Brown, Roberta Wyn and Vivian Ojeda, "Access to Health Insurance and Health Care for Children in Immigrant Families," UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, June 1999.

7. General Accounting Office, "Medicaid: Demographics of Nonenrolled Children Suggests State Outreach Strategies," GAO/HEHS-98-93, March 1999.

8.

Kathleen Maloy, et al. "Effect of the 1996 Welfare and Immigration Reform Laws on Immigrants' Ability and

Willingness to Access Medicaid and Health Care Services: Findings from Four Metropolitan Sites," Center for

Health Services Research and Policy, George Washington Univ., May 2000. Depts. of Health and Human Services

and of Agriculture, "Guidance to State Health and Welfare Officials on Inquiries into Citizenship, Immigration

Status and Social Security Numbers in State Applications for Medicaid, State Children's Health Insurance Program

(SCHIP), Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) and Food Stamp Benefits," Sept. 21, 2000.

9. The CPS asks about insurance status in the prior year and is generally interpreted as indicating whether a

person has any insurance coverage of a given type during the prior year. A person shown as uninsured should have

lacked insurance the entire year. By contrast, a person reporting Medicaid coverage might have had this coverage

for one month during the year. The CPS does not differentiate between legal and undocumented noncitizen

immigrants, although many analysts believe undocumented aliens are less likely to be included in the survey.

10. Among low-income children from native citizen families, there were 1.9 million fewer children on Medicaid in

1999 than 1995. Some of the reduction in the number of children on Medicaid or SCHIP is because there were

fewer low-income children in 1999 than 1995, because of improved economic conditions and reduced poverty.

11. A child with immigrant parents is defined as one who has at least one parent who is not a citizen. Table 1 does

not include data about citizen children with naturalized-citizen parents. The insurance profile of these children is

similar to that of native citizens' children.

12. A more rigorous statistical analysis found that citizen children with noncitizen parents had significantly lower

Medicaid and job-based insurance and higher uninsurance rates than children of native citizens, after controlling for

parental income, education, and race/ethnicity and other related demographic factors. See Ku and Matani, op cit.

13. One possible explanation for these puzzling data is that some immigrant parents may have misidentified

managed care plans in which they were enrolled under Medicaid or SCHIP as other private coverage. In that case,

Medicaid coverage would have increased more than the Census data indicate. Another possibility is that some of the

immigrant parents simply misunderstood the questions and answered them incorrectly. Finally, this might be a

spurious result of the type that sometimes happens in sample surveys like the CPS. This change between 1998 and

1999 in other private insurance coverage is not consistent with data for earlier years, but it is not possible to know

whether this means the new data are invalid or there was an actual improvement in coverage rates.

14. In May 1999, the Immigration and Naturalization Service released guidance to clarify that receipt of Medicaid

or SCHIP (except for long-term care) would not be considered grounds for determining that an immigrant might

become a "public charge." This policy change was intended to reduce fears in some immigrant communities that

receiving Medicaid might endanger a family member's immigration status. Such fears were stimulated by some

public charge enforcement actions that occurred in the mid-1990s.

15. Angela Brittingham, "The Foreign-Born Population in the United States," Current Population Reports, P20-519, U.S. Census Bureau, August 2000.

16. Brown, et al., op cit.

17. Ku and Matani, op cit.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.