- Home

- What If Ryan's Medicaid Block Grant Had ...

What if Ryan's Medicaid Block Grant Had Taken Effect in 2000?

Federal Medicaid Funds Would Have Fallen over 25% in Most States, Over 40% in Some, by 2009

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan’s radical proposal to convert Medicaid to a block grant, which the House will consider this week as part of Ryan’s sweeping budget plan, would have cut federal Medicaid funds to most states by more than 25 percent by 2009 and to several of them by more than 40 percent if it had been in effect starting in 2000, according to a new Center on Budget analysis.

Every state would have received substantially less from the federal government than it actually received under current law, but some states would have received much, much less. States where cuts would have topped 40 percent in 2009 include Arizona, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, and Oklahoma, and states where cuts would have exceeded 30 percent include Alaska, Arkansas, California, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

The Ryan plan would fundamentally restructure Medicaid by converting it to a block grant. In addition to eliminating the Medicaid expansion under last year’s health reform law, leaving millions of low-income individuals who would otherwise gain health coverage uninsured, the plan would further boost the number of uninsured or underinsured Americans by cutting the current Medicaid program by $771 billion over the next 10 years through its block grant proposal (or 22.4 percent compared to current law). [1]

The block grant would start in 2013 and cap federal Medicaid funding at levels well below what the existing system would provide. Federal Medicaid funding would be cut 35 percent by 2022 and 49 percent by 2030, according to the Congressional Budget Office. [2] As a result, the block grant would sharply shift costs to states, beneficiaries, and health care providers over the next 10 years and the decades thereafter. States would have to offset the federal funding shortfalls by substantially boosting their own contributions to Medicaid or using the greater flexibility that a block grant would provide to make deep cuts to eligibility, health and long-term care services, and provider reimbursement rates, as CBO notes. That would likely mean many more low-income Americans who are uninsured, underinsured, or have less access to needed care. [3]

To help illustrate how states would likely fare under the Ryan block grant over time, we have estimated what the state-by-state effects would have been if it had been in effect between 2000 and 2009, based on the Ryan block grant’s specifications as outlined by CBO. We compare how much states would have received in federal funding under the block grant for fiscal years 2000 through 2009 to the actual federal funding they received during this period (not counting the additional Medicaid funds that states received in fiscal years 2003, 2004 and 2009 as a result of federal legislation that temporarily increased federal Medicaid matching rates in response to weak economic conditions).

Our findings show that:

- States would have received $350 billion — or 21 percent — less over this period than they actually did.

- In 2009 alone, the cuts in federal funding would have equaled an estimated $63.5 billion, a reduction of 29 percent.

- While the Ryan block grant would have hit all states hard over the 10-year period, it would have produced disparate effects, with some states made substantially worse off than others.

The Ryan Plan’s Medicaid Block Grant

Under the Ryan plan, the Medicaid program would be converted into a block grant, starting in 2013. Instead of the federal government picking up a fixed percentage of states’ Medicaid costs as it does today, it would provide each state with a fixed dollar amount, with states responsible for all remaining Medicaid costs.

According to CBO, the total block grant amount available to states each year would be adjusted annually by general inflation (i.e., by the annual percentage growth rate in the Consumer Price Index) plus the percentage growth rate in the size of the U.S. population. The Ryan budget plan does not specify how the block grant amount would be determined in its first year, but Medicaid block grant proposals typically have set the initial grant amount equal to actual federal Medicaid spending in the prior fiscal year (in this case, 2012), increased by the annual adjustment factor.

The annual adjustment under the Ryan Medicaid block grant would, on average, be about 3.5 percentage points less than the current projected growth rate for the Medicaid program over the next 10 years (which takes into account, among other things, rising health care costs and an aging population — elderly beneficiaries cost about five times as much, on average, to insure as non-elderly, non-disabled adults). The gap would be as much as 4.8 percentage points in 2021.[4] This largely explains how the Ryan budget would result in cuts to Medicaid of $771 billion between fiscal years 2012 and 2021. [5] (This amount does not include the additional $627 billion in federal Medicaid funding reductions under the Ryan budget that would result from repeal of the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.)

Over the coming decade, Medicaid funding for states would be 22.4 percent less than what is projected to be provided under current law (excluding the Medicaid expansion), with the reductions starting at 4.7 percent in 2013 and rising to 33 percent by 2021 (see Table 1). The depth of the cuts would continue to grow rapidly in subsequent years; CBO reports that by 2022, federal Medicaid funding would be 35 percent below what would be provided under the current program, and by 2030, the reduction would be 49 percent. In other words, by 2030, the program would be cut nearly in half.

| TABLE 1: Medicaid Cuts Under Ryan Budget Plan Over Next 10 Years (in billions of dollars) | |||||||||||

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2012 -2021 | |

| Repeal of Medicaid Expansion | 0 | 0 | -30 | -55 | -77 | -84 | -87 | -93 | -97 | -105 | -627 |

| Cuts to Medicaid Program (Excluding Expansion) | -1 | -13 | -44 | -63 | -73 | -82 | -102 | -112 | -131 | -150 | -771 |

| Percentage Cut to Medicaid Program (Excluding Expansion) | 0 | -5 | -15 | -21 | -22 | -24 | -28 | -29 | -31 | -33 | -22 |

| Source: CBPP analysis of CBO March 2011 Medicaid Baseline and House Budget Committee, “Path to Prosperity, April 5, 2011. Figures may not sum due to rounding. | |||||||||||

To compensate for federal funding reductions of this magnitude, states would have to provide substantially more state funding (by raising taxes or cutting other programs) or, as is much more likely, cut back their programs substantially by scaling back eligibility (and covering many fewer low-income families and individuals), cutting back the health and long-term care services and supports that Medicaid covers, and further lowering reimbursement rates to providers. Such cuts could add millions to the ranks of uninsured. They also could impede access to needed care for tens of millions of people who continued being covered, as a consequence of sharply curtailed benefits and substantial increases in co-payment and premium charges, or as a result of sharp cuts in provider reimbursements that cause substantial numbers of doctors, hospitals, nursing homes, and other health providers to withdraw from the program and no longer serve Medicaid beneficiaries.

Estimating the State-by-State Impact If the Ryan Medicaid Block Grant Had Been in Effect Over the Last Decade

Our findings show that actual federal Medicaid spending would have outpaced growth in the block grants by an average of about 3.7 percentage points per year. As a result, federal Medicaid funding would have been $350 billion (or 21 percent) less than was actually provided between 2000 and 2009. In general, the magnitude of the cuts would have grown larger every year. (The sole exception would have been in 2006, when actual federal Medicaid spending declined due to the transfer from Medicaid to Medicare of prescription drug costs for the “dual eligible” population — that is, for low-income beneficiaries enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid — as a result of the institution of the Medicare prescription drug benefit. By 2009, the reductions in federal Medicaid funding would have equaled an estimated $63.5 billion, or 29 percent. (See the appendix.)

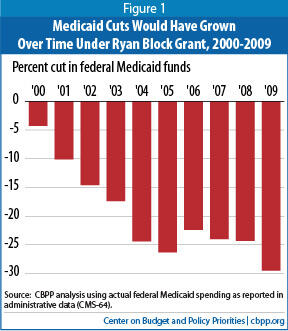

The largest jumps in the size of the cuts would have occurred during years in which the economy slumped. In a recession, when people lose their jobs and access to employer-sponsored insurance, many become eligible for and enroll in Medicaid. For example, during the recession in the early years of the decade, Medicaid enrollment grew by a total of 7.8 million people (or 24 percent) between December 2000 and December 2003. [7] Under current law, federal Medicaid funding automatically increases to offset these higher enrollment costs; under a block grant, however, states would receive no additional funding. [8] The reductions (expressed as a percentage cut, relative to the amount of federal funding actually provided) would have risen from 4 percent in 2000 to 24 percent by 2004, when states were still experiencing rapid increases in their Medicaid caseloads. The magnitude of the cuts would then have remained relatively level (in percentage terms) for a few years, as unemployment fell and enrollment declined (and also as a result of the Medicare drug benefit). But in 2009, the first year of the recent recession, the size of the cuts would have begun increasing very substantially again (see Figure 1).

The effects of the block grant on individual states also would have varied widely. While all states would have faced substantial reductions in federal funding, some states would have faced particularly severe cuts in Medicaid funding. This would likely have been due to state-by-state differences in initial relative spending and annual spending growth rates over time as compared to other states (including differences in how states fared during economic downturns and whether they experienced larger-than-average enrollment increases, as well as other differences due to a range of factors including state-by-state differences in demographics and in the rate of growth in health care costs). [9] For example:

- Arizona would have been hit the hardest, receiving 52 percent less in federal Medicaid funding over the 10-year period. The five states that would have experienced the largest percentage reductions — Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Alaska and Florida — would have experienced average cuts of 39 percent over ten years (and average cuts of 47 percent in 2009).

- The five states with the smallest reductions would have been cut an average of 9 percent over the 10-year period (and 17 percent in 2009). These states are Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Nebraska, New Hampshire and North Dakota). (See the appendix.)

| Appendix Estimated Cuts If Ryan Medicaid Block Grant Had Been in Effect, 2000-2009 ($ millions) | ||||

| STATE | Reduction in Federal Funds, 2000-2009 | Percentage Cut, 2000-2009 | Reduction in Federal Funds, 2009 | Percentage Cut, 2009 |

| NATION | -$350,044 | -21% | -63,531 | -29% |

| Alabama | -4,517 | -18% | -628 | -20% |

| Alaska | -2,036 | -36% | -260 | -39% |

| Arizona | -18,735 | -52% | -3,895 | -66% |

| Arkansas | -6,033 | -31% | -998 | -39% |

| California | -35,259 | -20% | -6,997 | -31% |

| Colorado | -2,054 | -15% | -478 | -26% |

| Connecticut | -1,689 | -8% | -751 | -26% |

| Delaware | -1,393 | -31% | -286 | -45% |

| DC | -798 | -9% | -260 | -22% |

| Florida | -22,386 | -32% | -3,054 | -35% |

| Georgia | -12,152 | -30% | -1,844 | -36% |

| Hawaii | -1,752 | -31% | -305 | -41% |

| Idaho | -2,128 | -31% | -371 | -40% |

| Illinois | -9,303 | -17% | -1,852 | -27% |

| Indiana | -8,970 | -28% | -1,349 | -34% |

| Iowa | -3,825 | -25% | -573 | -30% |

| Kansas | -2,570 | -21% | -434 | -28% |

| Kentucky | -5,627 | -19% | -1,126 | -29% |

| Louisiana | -6,717 | -19% | -1,235 | -27% |

| Maine | -2,645 | -21% | -545 | -33% |

| Maryland | -5,323 | -22% | -1,160 | -34% |

| Massachusetts | -9,884 | -21% | -2,173 | -34% |

| Michigan | -5,868 | -12% | -1,456 | -22% |

| Minnesota | -7,190 | -25% | -1,441 | -37% |

| Mississippi | -6,784 | -28% | -1,046 | -34% |

| Missouri | -10,556 | -28% | -1,851 | -37% |

| Montana | -1,215 | -25% | -208 | -33% |

| Nebraska | -885 | -10% | -122 | -12% |

| Nevada | -2,205 | -38% | -324 | -44% |

| New Hampshire | -530 | -9% | -101 | -14% |

| New Jersey | -5,124 | -12% | -702 | -14% |

| New Mexico | -6,456 | -38% | -1,220 | -50% |

| New York | -24,901 | -12% | -3,528 | -14% |

| North Carolina | -13,802 | -26% | -2,656 | -37% |

| North Dakota | -346 | -10% | -36 | -9% |

| Ohio | -16,676 | -25% | -3,094 | -35% |

| Oklahoma | -5,705 | -29% | -1,058 | -40% |

| Oregon | -2,440 | -13% | -622 | -25% |

| Pennsylvania | -13,381 | -17% | -2,170 | -22% |

| Rhode Island | -1,475 | -17% | -197 | -19% |

| South Carolina | -5,129 | -19% | -797 | -24% |

| South Dakota | -623 | -16% | -118 | -23% |

| Tennessee | -9,653 | -22% | -972 | -20% |

| Texas | -20,063 | -19% | -4,617 | -32% |

| Utah | -2,210 | -24% | -404 | -34% |

| Vermont | -1,400 | -27% | -269 | -38% |

| Virginia | -5,624 | -25% | -1,055 | -36% |

| Washington | -4,557 | -15% | -829 | -22% |

| West Virginia | -2,013 | -14% | -371 | -20% |

| Wisconsin | -6,867 | -24% | -1,598 | -40% |

| Wyoming | -572 | -25% | -94 | -32% |

| Source: CBPP analysis based on CMS Medicaid spending data. To determine states’ block grant amounts under the Ryan proposal, we use federal Medicaid spending in 1999 as the base, adjusted annually by national population growth and the growth in the Consumer Price Index. We exclude federal Medicaid spending related to temporary federal Medicaid matching rate increases in 2003, 2004 and 2009. | ||||

Medicaid Block Grant Would Produce Disparate and Inequitable Results Across States

End Notes

[1] The Ryan budget would cut Medicaid by a total of $1.4 trillion over the next 10 years. The repeal of the Medicaid expansion would account for $627 billion of these cuts, with the other $771 billion coming from the current Medicaid program.

[2] Congressional Budget Office, “Long-Term Analysis of a Budget Proposal by Chairman Ryan,” April 5, 2011.

[3] Edwin Park and Matt Broadus, “Medicaid Block Grant Would Shift Financial Risks and Costs to States,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 23, 2011.

[4] CBPP calculations based on CBO March 2011 Medicaid baseline, CBO March 2011 economic assumptions, and Social Security Administration population estimates.

[5] Under our estimates, a Medicaid block grant adjusted annually by inflation and population growth would produce nearly $500 billion in federal Medicaid funding reductions over 10 years, not the $771 billion in Medicaid cuts the Ryan plan contains. It thus appears that the Ryan plan may include large additional unspecified Medicaid cuts of more than $270 billion.

[6] CBPP calculations based on Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) data, excluding federal Medicaid spending resulting from the temporary increases in federal Medicaid matching rates that were in effect for fiscal years 2003, 2004 and 2009.

[7] Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, “Medicaid Enrollment: December 2009 Data Snapshot,” September 2010. Some of the enrollment increase for 2000-2003 was likely also due to Medicaid expansions for children that were funded through the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and greater participation among already-eligible children resulting from states’ adoption of simplified enrollment procedures and greater outreach efforts.

[8] Even under Medicaid’s current financing structure, states experienced difficulty absorbing the significantly higher Medicaid enrollment-related costs that resulted from the past two economic downturns, because those higher costs coincided with plummeting state tax revenues and large state budget shortfalls. Congress temporarily increased the federal share of state Medicaid costs in fiscal years 2003, 2004 and 2009.

[9] For a discussion of why certain states could face particularly severe cuts under a block grant relative to other states, see Edwin Park and Matt Broaddus, “Medicaid Block Grant Would Produce Disparate and Inequitable Results Across States,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 10, 2011.

More from the Authors