- Home

- Testimony Of Chad Stone, Chief Economist...

Testimony of Chad Stone, Chief Economist, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Before the Senate Committee on Budget

Chairman Murray, Ranking Member Sessions, and other members of the Committee. Thank you for the opportunity to testify today on the effect of political uncertainty on jobs and the economy.

Businesses and households of course deal with uncertainty of all kinds all the time. That’s the nature of a dynamic market economy. And politics ain’t beanbag. So we shouldn’t be surprised that people fight hard for their preferred policies. But political gridlock over economic and budget policy combined with brinksmanship over must-pass legislation has hurt economic performance and job creation as the economic recovery continues to struggle to gain traction more than four years after the formal end of the recession in June 2009.

Unfortunately, things seem to be getting worse rather than better as we face yet another threat to the economic recovery generated purely by politics and not by economic events per se. I want to make two overarching points in my testimony.

- First, make no mistake: while a government shutdown would be disruptive to the economy, a failure of the federal government to honor financial obligations that it has already incurred — whether to bondholders, government contractors, or veterans — would be disastrous. Evidence from the 2011 debt-ceiling crisis suggests that debt-ceiling brinksmanship is costly even if a last-minute deal is struck.

- Second, resolving budget issues to avoid a government shutdown or debt default is only half the battle. The specific measures taken matter just as much. Moreover, a stopgap deal or one that both sides are not committed to seeing enforced merely postpones the next showdown. That’s what happened in 2011. Hard decisions to address the challenge of achieving longer-term fiscal stabilization were assigned to a special committee and a budget enforcement mechanism was put in place that was supposedly so unpalatable to both sides that it would guarantee an agreement. But here we are with sequestration, a possible government shutdown, and a debt-ceiling crisis.

There’s a broader lesson here. Commissions (or super committees) and budget rules don’t work without policymakers who are committed to the goal of fiscal stabilization and willing to make compromises in the interest of avoiding serious harm to the economy and in the interest of sound budgeting. Discretionary caps and PAYGO rules helped policymakers adhere to the 1990 and 1993 budget agreements, which together with a strong economy led to budget surpluses and declining debt by the end of the 1990s. But budget rules and deficit-control measures cannot force unwilling policymakers to make choices they see as unpalatable or bridge fundamental policy differences that leave little room for compromise.

The problem is even more difficult in a weak economy where larger deficits are appropriate in the short-term to support an economic recovery, but policymakers must also demonstrate a commitment to longer-term deficit reduction.

The Effect of Uncertainty and Budget Restraint in a Weak Economy

The legacy of the gut-wrenching financial crisis of 2008 and the confidence-sapping descent into the Great Recession is an economy that is still operating well below its full potential to supply goods and services. Employment is well below what it would be in a normal job market, due to a combination of high official unemployment and low labor force participation.

Besides the 11.3 million people officially counted as unemployed, there are many people who want a job and would likely find one in a stronger job market but remain sidelined until job prospects improve. Many among the employed would like to be working full-time but have only been able to find part-time work. Altogether about 22 million people are unemployed or underemployed.

It is widely, although I’ll admit not universally, accepted among economists that the major factor holding back economic growth and job creation is weak overall demand for goods and services. Businesses have the capacity to hire more people and produce more but they are held back from doing so by weak sales. At the same time, high unemployment and slow-to-nonexistent growth in wages and income hold down household spending, especially if households are rebuilding their balance sheets after earlier financial losses. Something needs to happen to get the economy out of this self-reinforcing low-demand trap.

Fiscal stimulus is one way to do that. It is generally, although once again not universally, accepted among economists that changes in taxes and government spending have a larger effect on economic activity and employment when there is substantial economic slack (an “output gap” between what is actually being produced and what could be produced with normal levels of demand and employment). That effect is even stronger when the use of traditional monetary policy is constrained by very low interest rates (the so called “zero lower bound”). That’s certainly the conclusion of a recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) reassessment of fiscal policy after the crisis:

While debate continues, the evidence seems stronger than before the crisis that fiscal policy can, under today’s special circumstances, have powerful effects on the economy in the short run. In particular, there is even stronger evidence than before that fiscal multipliers are larger when monetary policy is constrained by the zero lower bound (ZLB) on nominal interest rates, the financial sector is weak, or the economy is in a slump. A number of studies have also questioned the earlier evidence of negative fiscal multipliers associated with expansionary fiscal contractions.[1]

In other words, what the IMF is saying in its restrained and technocratic way is that under the conditions prevailing in the United States in recent years, the idea that cutting government spending in hopes of stimulating economic activity — so called “expansionary austerity” — is invalid. Cutting spending in a weak economy reduces output and employment — and the effects are powerful. Conversely, as the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has pointed out in its assessments of the effect of the Economic Recovery Act on output and employment, each dollar spent in a weak economy on government purchases of goods and services or transfer payments to low- and moderate-income individuals through programs like unemployment insurance and SNAP — payments they are likely to spend rapidly — can generate well over a dollar of additional economic activity, creating jobs and lowering unemployment.[2]

CBO reports a range of estimates of the impact of the Recovery Act (ARRA). The IMF analysis suggests the effect was at the high end of those estimates. According to CBO, at its peak impact in 2010, ARRA boosted real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP) by as much as 4.1 percent above what it otherwise would have been and created as many as 4.7 million additional full-time-equivalent jobs.

The economy has generated plenty of uncertainty on its own in recent years, but policy squabbles over how fast to implement needed long-term deficit reduction without harming the economic recovery and the appropriate mix between spending restraint and revenue increases has exacerbated the situation. Businesses, households, and financial markets had to deal with uncertainty over policy decisions in the run-up to critical decisions about expiring tax cuts and stimulus measures like emergency unemployment insurance at the end of 2010, 2011, and the big one, the 2012 “fiscal cliff.” The greatest uncertainty surrounded how the showdown over raising the debt limit in 2011 would be resolved.

Evidence suggests that businesses, households, and financial markets experience heightened uncertainty during such times and that that greater uncertainty acts as “anti-stimulus,” weakening aggregate demand. Failure to resolve the underlying issues or implementing policies that themselves restrain aggregate demand continues the uncertainty and the drag on the recovery.

A 2012 analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco[3] finds evidence, for example, that

…uncertainty harms economic activity, with effects similar to a decline in aggregate demand. The private sector responds to rising uncertainty by cutting back spending, leading to a rise in unemployment and reductions in both output and inflation. We also show that monetary policymakers typically try to mitigate uncertainty’s adverse effects the same way they respond to a fall in aggregate demand, by lowering nominal short-term interest rates.

The study concludes, however, that in the recent recession and recovery,

…nominal interest rates have been near zero and couldn’t be lowered further. Consequently, uncertainty has reduced economic activity more than in previous recessions. Higher uncertainty is estimated to have lifted the U.S. unemployment rate by at least one percentage point since early 2008.

In short, when the economy is weak and interest rates are very low, heightened uncertainty reduces demand for goods and services and the Fed is less able to provide an offsetting boost. The resulting net reduction in private spending leads to less job creation and higher unemployment.

Deficit-reduction policies have a similar effect. With respect to sequestration, for example, the Congressional Budget Office estimated in July that if the automatic spending reductions in effect in 2013 were cancelled in August and none of the reductions scheduled for 2014 were implemented, real (inflation-adjusted) GDP would be 0.7 percent higher in the third quarter of 2014 (the end of fiscal year 2014) and there would be about 900,000 more jobs than the levels CBO was projecting with sequestration in place.

Those are CBO’s central estimates; CBO provides a range for the estimated impacts. If the evidence that fiscal multipliers are particularly high under current conditions is correct, those gains from eliminating sequestration are toward the high end of CBO’s range: 1.2 percent higher GDP and 1.6 million more jobs.

The remainder of my testimony focuses on the importance of removing the debt ceiling as a source of brinksmanship and policy uncertainty, principles for achieving a sound budget deal, and a brief note on why the individual mandate is a critical piece of the Affordable Care Act and not something that can be bargained away in return for an increase in the debt ceiling.

Raze the Debt Ceiling

Congress should not be using the debt limit as a political football. In fact, the United States should not even have a debt limit.

The 2011 debt-limit showdown was not pretty, and even though a default was averted, the economy and the budget did not escape unharmed. As Urban Institute Fellow Donald Marron, a former acting CBO director and a member of President George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers, testified last week before the Joint Economic Committee, “brinksmanship does not come free.”

First, through accident or miscalculation, games of chicken can sometimes end in a crash, and the costs to the United States of actually defaulting on its financial obligations could be very high. Default means the Treasury says to someone, or as Marron says perhaps millions of someones, “Sorry you aren’t getting paid.” There’s no way to decide who gets paid in a way that does not damage the economy. If prolonged, a situation in which the Treasury is required to match payments to available cash would have an economic effect like sequestration plus the fiscal cliff on steroids and would likely plunge the economy back into recession. The difference between default and a government shutdown, sequestration, or the fiscal cliff is that even if the debt limit were subsequently raised, the damage to U.S. credit rating could not be reversed.

Second, the mere risk of default is likely to raise Treasury borrowing costs while a debt-ceiling showdown plays out. Marron cites the 2012 report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), estimating that delays in raising the debt limit in 2011 raised fiscal year 2011 Treasury borrowing costs by $1.3 billion[4] and the report by the Bipartisan Policy Center estimating that those costs would total $18.9 billion over the full maturity of the securities issued.[5]

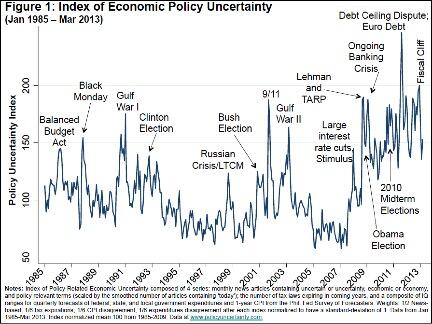

Third, the 2011 debt-ceiling showdown produced a marked spike in various measures of uncertainty and a marked decline in consumer confidence. The chart below, for example, shows the Index of Economic Policy Uncertainty developed by economists Scott R. Baker, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis.[6] The spike associated with the debt ceiling crisis is substantially larger than those associated with the fiscal cliff or the Lehman bankruptcy and the financial stabilization legislation (TARP).

In light of the evidence linking increases in uncertainty to the economy, it is reasonable to infer some economic harm. In a Wall Street Journal op-ed, Bill McNabb, Chairman and CEO of the Vanguard Group, reports that economists there estimate that the spike in policy uncertainty surrounding the debt-ceiling debate cost the economy $112 billion in lost output and likely many hundreds of thousands of jobs in the ensuing two years.[7] Economists Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers also point to evidence that employers probably held back on hiring.[8] While the U.S. and European debt crises are paired in the chart, Stevenson and Wolfers observe that the real trouble in Europe came after consumer confidence and employment in the U.S. were recovering.

Finally, the 2011 crisis damaged the United States’ financial reputation. As Marron points out, “Debating intentional default contributes to the perception that the United States does not know how to govern itself.” Stevenson and Wolfers point out that “The sense that the U.S. political system could no longer credibly commit to paying its debts led the credit-rating company Standard & Poor’s to remove the U.S. government from its list of risk-free borrowers with gold-standard AAA ratings.”

We at CBPP think this time looks even worse.[9] Congress on occasion in recent decades has attached both fiscal and non-fiscal items to debt limit legislation. But, on those occasions, the parties in question generally agreed that defaulting on the debt was not the desired outcome if they didn’t get their way. They sought to attach their proposals to what they probably regarded as must-pass legislation — sometimes they succeeded, sometimes they failed — and Congress then raised the debt limit to avoid a default.

The same thing could ultimately happen this year. But, increasingly, this year’s unfolding drama seems fundamentally different. The tactic of threatening to withhold votes on raising the debt limit unless the legislation includes a delay or repeal of health reform isn’t just about trying to attach favored legislative items to a bill that’s certain to pass anyway; it’s about holding the debt limit bill hostage and actually defaulting unless Congress adds policy changes that otherwise cannot be enacted on their own.

Nor should policymakers fool themselves into thinking that directing the Treasury to pay bondholders and Social Security recipients first if there’s a prolonged standoff over raising the debt ceiling is not simply default by another name.[10] This “debt prioritization” is extremely dangerous, and is probably not even be feasible, as Mark Zandi has testified at this hearing. By appearing to make defaulting on the debt legitimate and manageable, it would heighten the risk that a default will actually occur.

In reality, debt prioritization would make things worse for the millions of people and businesses who count on timely federal payments. Protecting bondholders and Social Security beneficiaries would leave even less cash on hand to pay veterans, doctors and hospitals who treat Medicare patients, soldiers, state and local governments, private contractors, and recipients of unemployment insurance, SNAP, and Supplemental Security Income.

The Treasury makes roughly 80 million separate payments each month, so deciding which bills to pay would be extremely difficult. And, domestic and foreign lenders would hardly be reassured at the sight of a cash-strapped superpower picking which bills it could afford to pay.

One rating agency explicitly warned in January that honoring interest and principal payments but delaying payment on other obligations would trigger a review and hence a possible downgrade. The Economist called failing to raise the debt limit — or attempting to prioritize payments — an “instrument of mass financial destruction.”

We should never get to the point of default — or even consider getting to it. We should not legitimize the idea of a default. We should consider the possibility beyond the pale. The potential costs to the economy, to U.S. and global markets, and to America’s standing in the world are simply too great.

Ideally, policymakers would abolish the debt limit, eliminating all risk that the government won’t pay its bills on time. To my knowledge, only one other developed country, Denmark, has a statutory debt limit anything like ours. Both have put a dollar limit on how much debt the government can issue. There's a crucial difference, however, between our debt limit and Denmark's: the Danes do not play politics with theirs, as Jacob Funk Kirkegaard of the Peterson Institute for International Economics explains:[11]

The Danish fixed nominal debt limit – legislatively outside the annual budget process – was created solely in response to an administrative reorganization among the institutions of government in Denmark and the requirements of the Danish Constitution. It was never intended to play any role in day-to-day politics.

When the financial crisis caused a sharp increase in government debt in 2008-2009, the Danes raised their debt ceiling — a lot. The 2010 increase doubled the existing ceiling, which was already well above the actual debt, to nearly three times the debt at the time. As Kirkegaard reports, “The explicit intent of this move — supported incidentally by all the major parties in the Danish parliament — was to ensure that the Danish debt ceiling remained far in excess of outstanding debt and would never play a role in day-to-day politics.”

The Constitution gives Congress power over federal borrowing, which it has exercised for decades through the statutory limit on federal debt. But the government is also legally bound to honor its financial obligations. Holding the debt limit hostage risks provoking a governance crisis in which the President is forced to choose between breaking the law by ignoring the debt ceiling or breaking the law by not paying government obligations in a timely manner. In terms of economic damage, the former is by far the better choice.

A Bad Deal to Avoid Default Would Hurt the Economy

The last debt-ceiling crisis produced an outcome nobody was supposed to want — sequestration — because of political gridlock over a long-term solution. CBPP has developed four criteria for evaluating any deal that emerges as we head toward zero hour for authorizing government spending for fiscal year 2014 and raising the debt ceiling, or as part of later negotiations after any temporary stopgap measures:[12]

1) Does it strengthen or weaken the economic recovery?

The Federal Reserve's monetary-policy-making committee decided last week that the economic recovery is not solid enough to start phasing down any of the measures it's been using to stimulate economic activity. One factor influencing the Fed's decision was surely a concern with the damage to the recovery that a government shutdown, or worse, a debt default would cause.

That damage would come on top of the drag on economic growth from fiscal tightening at the federal and state and local levels that's been underway since the stimulus from the 2009 Recovery Act peaked in 2010, including sequestration.

An ideal budget plan would replace sequestration with sizeable deficit-reduction measures that take effect gradually as the economy and labor market strengthen as well as temporary, up-front measures to boost job creation now. Such a policy would both strengthen the economy in the short term and produce more total deficit reduction and a better long-run debt trajectory than sequestration beyond the first decade.

Such a solution is fully consistent with the IMF analysis cited earlier[13] of what we have learned about fiscal policy in the wake of the financial crisis:

The design of fiscal adjustment programs, and particularly the merit of frontloading, has returned to the forefront of the policy debate. Given the nonlinear costs of excessive frontloading or delay, countries that are not under market pressure can proceed with fiscal adjustment at a moderate pace and within a medium-term adjustment plan to enhance credibility. Frontloading is more justifiable in countries under market pressure, though even these countries face “speed limits” that govern the desirable pace of adjustment. The proper mix of expenditure and revenue measures is likely to vary, depending on the initial ratio of government spending to GDP, and must take into account equity considerations.

The United States is not under market pressure and hence has no need to pursue short-term deficit reduction aggressively. In fact, given the IMF’s assessment of fiscal multipliers in a weak economy with very low interest rates and inflation, such a policy would be counterproductive. Issues of equity and the proper mix of expenditure and revenue measures deserve careful evaluation.

The IMF was very pointed about this following its latest annual consultation mission with U.S. policymakers:

On the fiscal front, the deficit reduction in 2013 has been excessively rapid and ill-designed. In particular, the automatic spending cuts (“sequester”) not only exert a heavy toll on growth in the short term, but the indiscriminate reductions in education, science, and infrastructure spending could also reduce medium-term potential growth. These cuts should be replaced with a back-loaded mix of entitlement savings and new revenues, along the lines of the Administration’s budget proposal. At the same time, the expiration of the payroll tax cut and the increase in high-end marginal tax rates also imply some further drag on economic activity. A slower pace of deficit reduction would help the recovery at a time when monetary policy has limited room to support it further.[14]

2) Does it protect low-income Americans and avoid increasing poverty and hardship?

In deficit-reduction efforts in 1990, 1993, and 1997, leaders of both parties embraced the principle that any deal should not increase poverty or impose additional hardship on low-income Americans. Fiscal commission co-chairs Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles embraced the same principle in their plan.

Last week's Census Bureau report on income, poverty, and health insurance suggests that any upcoming budget deal should adhere to the same principle. As CBPP President Robert Greenstein noted, “the new Census figures demonstrate that the painfully slow and uneven economic recovery has yet to produce significant gains for Americans in the bottom and middle of the economic scale.”

3) Does it adequately fund public services?

Yielding to Republicans' demands for more large immediate spending cuts would not only threaten the recovery but also savage important government services. The House-passed budget resolution of this spring would set overall discretionary (non-entitlement) funding at the post-sequestration level but shift tens of billions of dollars from non-defense programs to defense. That would require programs in the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services and Education be cut 18.6 percent below their 2013 post-sequestration levels.

Discretionary funding would shrink even without such large cuts. The cuts required under the Budget Control Act that President Obama and Congress enacted after their last debt-ceiling showdown would, by 2017, reduce non-defense discretionary spending — even without sequestration — to its lowest level on record as a percent of GDP, with data going back to 1962.

4) Does it strike a reasonable balance between spending and revenues and between defense and non-defense?

Deficit-reduction efforts since 2010 have tilted heavily toward spending cuts. Excluding sequestration, roughly 70 percent of the policy savings have come from program cuts and 30 percent from revenue increases. If sequestration continues, the ratio will move closer to 80-20. Revenues should account for a larger portion of future policy savings if we are to avoid savage cuts to important government services, anti-poverty programs and key entitlement benefits — and, thus to avoid exacerbating inequality and constraining opportunity.

Policymakers designed sequestration to pressure both parties to reach a budget deal by requiring that cuts come half from defense and half from non-defense programs, thus giving both conservatives and liberals a reason to replace sequestration with a more thoughtful approach. Efforts to shield defense and put all of the burden on non-defense would reduce conservative incentives to compromise.

To repeat, resolving budget issues to avoid a government shutdown or debt default is only half the battle. The specific measures taken matter just as much.

A Note on Why the Individual Mandate Is an Essential Feature of the Affordable Care Act

Opponents of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) health reform legislation want to see it repealed or crippled, and their ardent desire to see it used as a bargaining chip in the debt-ceiling debate introduces a major element of uncertainty. It is important to recognize, however, that the individual mandate requiring everyone to acquire health insurance as long as it's affordable is critically important for enabling health reform to achieve its goals of increasing coverage and controlling costs. It is much more significant than responsibilities placed on businesses to offer health insurance.

As my CBPP colleague Edwin Park explains,[15] starting in 2014 the ACA prohibits insurers from denying coverage to people with pre-existing conditions or charging sick people higher premiums. Without the individual mandate, those reforms would encourage older, sicker people to buy insurance but would give younger, healthier people an incentive not to do so until they became sick. Premiums would rise as the pool of insured people became older, sicker, and smaller. As Park reports:

Specifically, a one-year delay of the individual mandate would raise the number of uninsured Americans by about 11 million in 2014, relative to current law, and would reduce the expected coverage gains under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) by nearly 85 percent, according to a new [Congressional Budget Office] estimate. Delaying the individual mandate also would raise premiums for health insurance purchased in the individual market in 2014, CBO finds.

Proponents of delaying the individual mandate draw a false analogy between it and the Obama administration's delay in implementing the law's employer responsibility requirement for a year. As my CBPP colleague Judy Solomon has pointed out,[16] the vast majority of large employers — the only companies that are subject to the requirement to offer coverage and the related penalty if they don't — already offer health coverage and are unlikely to stop. Moreover, as Solomon says:

What’s key is that the delay won’t affect a core component of health reform: in 2014, workers who do not get coverage through their jobs will be able to get good coverage in the new marketplaces, with subsidies available to those with low and moderate incomes.

Averting a Budget Crisis Is Not Enough: Criteria for Evaluating Fall Budget Proposals

Delaying the Individual Mandate Would Result in Millions More Uninsured and Higher Premiums

End Notes

[1] IMF Policy Paper, “Reassessing the Role and Modalities of Fiscal Policy in Advanced Economies,” International Monetary Fund, September 2013, http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2013/072113.pdf.

[2] Congressional Budget Office, “Estimated Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act on Employment and Economic Output from October 2012 Through December 2012,” Table 2, CBO, February 2013.

[3] Sylvain Leduc and Zheng Liu, “Uncertainty, Unemployment, and Inflation,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter 2012-28, September 17, 2012, http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2012/september/uncertainty-unemployment-inflation/.

[4] GAO, “Debt Limit: Analysis of 2011-2012 Actions Taken and Effect of Delayed Increase on Borrowing Costs,” Government Accountability Office, July 2012, http://www.gao.gov/assets/600/592832.pdf.

[5] Bipartisan Policy Center, “Debt Limit Analysis,” September 2013, http://bipartisanpolicy.org/sites/default/files/Debt%20Limit%20Analysis%20Sept%202013.pdf.

[6] Scott R. Baker, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis, “Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty,” May 19, 2013, http://www.policyuncertainty.com/media/BakerBloomDavis.pdf.

[7] Bill McNabb, “Uncertainty Is the Enemy of Recovery,” Wall Street Journal, April 28, 2013, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323789704578443431277889520.html.

[8] Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers, “Debt Ceiling Déjà Vu Could Sink the Economy,” Bloomberg.com, May 28, 2012, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-05-28/debt-ceiling-deja-vu-could-sink-economy.html.

[9] Robert Greenstein, “Don’t Be Fooled: This Year’s Debt Limit Fight Is Frighteningly Different, Off the Charts blog, September 20, 2013, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/dont-be-fooled-this-years-debt-limit-fight-is-frighteningly-different/.

[10] Paul N. Van de Water, “ ‘Debt-Prioritization’ Is Simply Default by Another Name,” Off the Charts blog, September 19, 2013, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/debt-prioritization-is-simply-default-by-another-name/.

[11] Jacob Funk Kirkegaard, “Can a Debt Ceiling Be Sensible? The Case of Denmark II, Peterson Institute for International Economics, July 28, 2011, http://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime/?p=2292.

[12] Sharon Parrott, Richard Kogan, and Robert Greenstein, “Averting a Budget Crisis Is Not Enough: Criteria for Evaluating Budget Proposals,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 10, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4010.

[13] “Reassessing the Role and Modalities of Fiscal Policy in Advanced Economies,” International Monetary Fund, September 2013, http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2013/072113.pdf.

[14] International Monetary Fund, “Concluding Statement of the 2013 Article IV Mission to The United States of America,” IMF, June 14, 2013, http://www.imf.org/external/np/ms/2013/061413.htm.

[15] Edwin Park, “Delaying the Individual Mandate Would Result in Millions More Uninsured and Higher Premiums,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 12, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4012.

[16] Judy Solomon, “Delay Won’t Keep People from Obtaining Health Coverage,” Off the Charts blog, July 3, 2013, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/delay-wont-keep-people-from-obtaining-health-coverage/.