- Home

- Testimony: Barbara Sard, Vice President ...

Testimony: Barbara Sard, Vice President for Housing Policy, Before the House Financial Services Subcommittee on Housing and Community Support

Thank you for the opportunity to testify. I am Barbara Sard, Vice President for Housing Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The Center is an independent, nonprofit policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income families. The Center's housing work focuses on improving the effectiveness of federal low-income housing programs, and particularly the Section 8 housing voucher program.

The Section 8 Savings Act (SESA) would take a series of important, timely steps to strengthen the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, the nation's most widely used low-income housing program. It also would simplify and streamline rent policies for all of HUD's major rental assistance programs. The bill would sharply reduce administrative burdens for state and local housing agencies and private owners, establish funding rules that would enable housing agencies to manage voucher funds more efficiently, and strengthen work supports, including opening up participation in the Family Self-Sufficiency program to families receiving project-based section 8 assistance.

Taken together, the bill's provisions would stretch limited funds to assist significantly more families than would be possible under current law, a crucial improvement at a time when budgets are tight and poverty and homelessness are high. We commend the subcommittee for moving forward with this bill.

The current SESA discussion draft contains many provisions that are similar to earlier versions of the Section 8 Voucher Reform Act (SEVRA), including H.R. 3045, which the Financial Services Committee passed in July 2009, and H.R. 1851, which the House passed by a bipartisan vote of 333-83 in July 2007. But it drops provisions of those bills that were costly, controversial, or that HUD could implement without new legislative authority. Some of the most important SESA provisions would:

- Simplify rules for setting tenant rent payments, while continuing to cap rents at 30 percent of the tenant's income.

- Streamline housing quality inspections to encourage private owners to participate in the program.

- Stabilize voucher reserve funds to enable agencies to better cope with funding shortfalls or unavoidable cost increases, and make other improvements in voucher funding policy.

- Support work by modestly raising income targeting limits to admit more working-poor families and strengthening the Family Self-Sufficiency program, which offers housing assistance recipients job counseling and incentives to work and save.[1]

These important reforms are expected to achieve considerable savings that could be used to extend assistance to more families or for deficit reduction. In 2010, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that provisions similar to those in the current bill would reduce the budget authority needed to fund the current level of housing assistance by more than $700 million over five years, primarily by serving more working-poor families who need lower subsidies to afford rent. Moreover, CBO did not attempt to estimate the administrative savings from SESA's streamlining provisions, which could lower costs by an added several hundred million dollars over five years.

Congress could make the bill even stronger by adding a number of cost-free, broadly supported provisions from earlier versions of SEVRA. The most important of these would:

- Improve the efficiency of the voucher funding system further by establishing a system to shift funds from agencies that are not using them to cover funding shortfalls or enable other agencies to assist more families.

- Help develop and preserve affordable housing by facilitating use of "project-based" vouchers (which, unlike more widely used "tenant-based" vouchers, can be tied to a particular development).

- Support use of vouchers in mobile homes by allowing a voucher to be used to cover both the rent for land on which to place a mobile home and loan payments and other costs of purchasing a home (subject to the same subsidy limits that apply to vouchers used for other purposes).

- Avoid duplication of effort by requiring state SNAP (formerly food stamp) agencies to share data with housing agencies on incomes of families participating in both programs.

- Expand agencies' flexibility to adjust voucher rent caps for disability-accessible units.

- Limit (or allow HUD to limit) tenant screening in all rental assistance programs to criteria relevant to a family's ability to responsibly rent a unit.

My testimony also includes recommended improvements to other the provisions in the draft bill.

The current SESA draft omits a risky provision that was included in H.R. 3045: an expansion of HUD's Moving-to-Work (MTW) demonstration. MTW is intended to test innovative housing policies, but it has proven to be an ineffective and inefficient way to pursue this goal. It will be important that Congress refrain from adding an MTW expansion as the legislative process moves forward.

Stabilizing Voucher Funding Rules

The most important goal for new authorizing legislation concerning the Housing Voucher Program is to establish a stable, fair, efficient policy for distributing funds to renew voucher subsidies to the approximately 2,400 state and local agencies that administer the program, enabling those agencies to assist more families than would otherwise be possible with the level of resources provided in annual appropriations bills. For the last eight years, appropriations acts have changed renewal funding policies every year or two. Such instability creates uncertainty and makes many agencies reluctant to use the funds they have to serve the number of families Congress has authorized, out of fear that they will not receive sufficient renewal funding to maintain payments to landlords. As a result, only about 92 percent of authorized vouchers are in use, compared to about 97 percent before the changes in renewal funding policy began — a loss of assistance to about 100,000 families.

Commendably, SESA includes three important components of a predictable renewal funding policy.

- The draft bill would assure state and local housing agencies that they can maintain a funding reserve of at least 6 percent of the renewal funding for which they are eligible. In the current funding environment, when agencies may fear that Congress will not provide sufficient new funding to support all vouchers in use, a predictable reserve level provides the cushion agencies need to reissue vouchers to needy applicants on the waiting list when families leave the program and be confident that they will have sufficient funds to sustain the vouchers.

- The draft bill would encourage agencies to reduce the cost of voucher subsidies and stretch their voucher funds to serve as many families as possible by restoring the flexibility that existed prior to 2003 to use available funds to serve more families. Under the "authorized voucher cap" policy adopted in annual appropriations acts since 2003, agencies are penalized if they use more than the authorized number of vouchers in a year, even if they can do so by reducing per-voucher costs. This policy has pushed agencies to use substantially fewer than their authorized number of vouchers out of fear of exceeding the cap. The draft bill would remove this chilling effect, and encourage agencies to keep per-voucher costs low. Agencies would be assured that if they take steps to limit costs, they could use any savings to provide vouchers to more families, even if this pushes them above their authorized voucher level. This important incentive would not, however, increase program costs, as vouchers above the authorized level that are supported by unused prior-year funds would not be eligible for renewal.

- The draft bill refers to a policy of basing agencies' renewal funding on their number of vouchers in use in the prior calendar year (although it does not explicitly require that HUD allocate funds in this manner). Experience has shown that in the absence of such re-benchmarking based on actual voucher utilization, the number of families receiving housing assistance declines precipitously.[2]

These measures are helpful, and by themselves would enable and encourage agencies to use available funds to help more needy families. SESA could accomplish much more, however, by addressing all of the essential elements that guide HUD's annual distribution of the funds Congress makes available for voucher renewals. With such a comprehensive renewal funding policy in place, appropriators could focus on their core function of determining how much funding to allocate for particular purposes, and agencies would know what rules would apply to whatever amount of funds Congress decides to provide.

Four additional provisions — all of which were in versions of SEVRA in the last Congress — are needed for a comprehensive policy that would make the most efficient use of renewal funding:

- The legislation should state explicitly that eligibility for renewal funding will be based on voucher spending ("leasing and costs") in the immediately preceding calendar year, adjusted by a HUD-determined projected local cost inflation factor. Basing funding on voucher utilization, without consideration of voucher costs, does not achieve the predictability needed to sustain the level of vouchers in use.

- In allocating renewal funds, HUD should be directed to offset each PHA's renewal funding eligibility by the amount of "excess" reserves above the established level (at least 6 percent, as noted above). A predictable offset policy ensures that assistance will be maintained for the maximum number of currently assisted families even in the event of a funding shortfall. Making such an offset predictable also provides a powerful incentive for agencies to put any excess unspent funds to use, by making clear that agencies will lose any funds beyond the permitted reserve amounts.

- Unused funds from the first year of a new voucher allocation should be excluded in determining the amount of reserves. Such a policy is critical, for example, when new vouchers are issued near the end of a year to protect tenants in a property that has ceased to receive project-based assistance.

- The legislation should authorize HUD to reallocate any renewal funds that may remain after full funding of agencies' formula eligibility based on objective criteria. In timely appropriations bills, Congress will determine the amount of renewal funding before all the data are available to know the precise amount of funding needed to fully fund the renewal formula. In recent years when such "excess" funding has been provided, HUD has been required to provide every agency a pro-rata share of the extra funds. It would increase the efficient use of appropriated funds to allow HUD to use any such funds to provide funding for unforeseen circumstances or to reward particularly high performance.

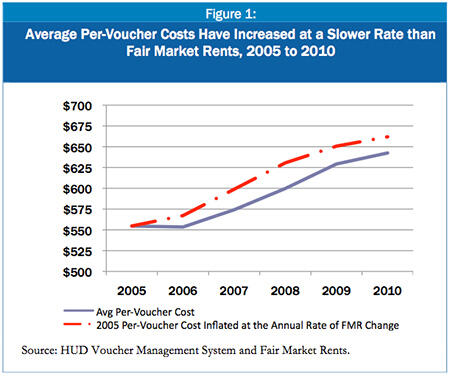

Per-Voucher Costs Have Risen More Slowly than Housing Costs in the Private Market

While the draft bill, particularly with the improvements recommended above, would create important incentives to keep per-voucher costs low, it is important to note that this would build on the voucher program's already successful record of restraining costs. Per-voucher costs have generally risen at a slower rate than housing costs in the private market. HUD-determined Fair Market Rents (FMRs), which are based in market rents for standard-quality unassisted units, increased by 19 percent from 2005 to 2010. During that same period, average per-voucher costs increased by less than 16 percent.

This is particularly striking because of evidence that the incomes of assisted households have also risen at a slower rate than market housing costs. Because voucher assistance payments fill the gap between tenant contributions and actual housing costs, and tenant contributions are based on a percentage of income, one would expect per-voucher costs to increase at a faster rate than market housing costs, if tenant incomes are rising at a slower rate. Yet evidence suggests that average tenant incomes rose by about 10 percent from 2005 to 2010, well below the increase in FMRs.

The mostly likely explanation is that housing agencies controlled voucher costs through their ability to set payment standards, which determine the maximum allowable voucher assistance payment and can be set anywhere from 90 to 110 percent of the FMR (and outside that range under some circumstances). This explanation receives support from HUD data showing that, on average, voucher payment standards declined in relation to FMRs from 2005 to 2010.

By incorporating such an improved voucher renewal funding policy in permanent law, SESA would provide agencies — as well as families with vouchers and private owners — with more confidence that renewal funding needs will be met in future years, which is particularly important to maintain program effectiveness in the current fiscal environment. The measures in SESA would not weaken Congress's control over the cost of the program. Congress would still determine the amount of annual program funding, and if the funds appropriated in a given year were insufficient to fully fund the renewal formula, HUD would reduce each agency's funding by the same percentage so funds would still be allocated based on agencies' relative needs. SESA would simply ensure that, for any given level of funding, more families would receive the important benefits that vouchers have been shown to provide.

Simplifying Rules for Determining Tenants' Rent Payments

Tenants in HUD's housing assistance programs generally must pay 30 percent of their income for rent, after certain deductions are applied. SESA would maintain this rule, but would streamline the process for determining tenants' incomes and deductions. As a result, the bill would reduce the burdens that rent determinations place on housing agencies, property owners, and tenants. The changes would also reduce the likelihood of errors in rent determinations and strengthen incentives for tenants to work.

Most significantly, SESA would:

- Reduce the frequency of required income reviews. Currently, agencies must conduct annual income reviews for all tenants, including those who receive most or all of their income from fixed income sources such as Social Security or SSI and consequently are unlikely to experience much income variation from one year to the next. SESA would allow agencies to review the incomes of tenants with fixed incomes every three years.[3]

Currently, agencies also must make rent adjustments between annual reviews at the request of any tenant whose income drops. SESA would require adjustments only when a family's annual income drops by 10 percent or more, thereby reducing the number of such "interim recertifications" that an agency must make while enabling tenants to obtain adjustments when they would otherwise face serious hardship. Interim rent adjustments would be required for increases in annual income exceeding 10 percent as well, except that to strengthen work incentives adjustments for increases in earnings would not occur until the next annual review..

Together, these changes would sharply reduce the number of income reviews that agencies and owners must conduct. Such reviews are among the most labor-intensive aspects of housing assistance administration, so such a reduction would substantially lower administrative costs. - Simplify deductions for the elderly and people with disabilities. Currently, housing agencies and owners are required to deduct medical expenses and certain disability assistance expenses that exceed 3 percent of a household's income if the household head (or his or her spouse) is elderly or has a disability. Agencies frequently state that this deduction is difficult to administer, since they must collect and verify receipts for all medical expenses. It also imposes significant burdens on elderly people and people with disabilities, who must compile and submit receipts that may contain highly personal information. Largely for these reasons, many households eligible for the deduction do not receive it. By contrast, a second deduction targeted to the same groups — a $400 annual standard deduction for each household headed by an elderly person or a person with a disability — is quite simple to administer.

SESA would increase the threshold for the medical and disability assistance deduction from 3 percent of annual income to 10 percent. This would reduce the number of people eligible for the deduction — and therefore the number of itemized deductions that would need to be determined and verified — while still providing some relief for tenants with extremely high medical or disability assistance bills. At the same time, SESA would substantially increase the easy-to-administer standard deduction for the elderly and people with disabilities to $675 annually and index it for inflation. In addition to reducing burdens on agencies, owners, elderly people, and people with disabilities, this change is likely to reduce payment errors substantially. HUD studies have found that the medical and disability expense deduction is one of the most error-prone components of the rent determination process, while errors in the standard deduction are rare.[4] - Simplify deductions for families with children. SESA would scale back an existing deduction for child care expenses — which evidence suggests is implemented inconsistently — by allowing deductions only of expenses above 5 percent of income (rather than all reasonable expenses). At the same time, it would increase from $480 to $525 a simple annual deduction that families receive for each child or other dependent and index it for inflation. The dependent deduction recognizes the larger share of family income required to cover non-shelter expenses when a family has more children.

- Base rents on a tenant's actual income in the previous year. Currently, rents are based on a tenant's anticipated income in the period that the rent will cover, usually the coming 12 months. Except when a family first begins receiving housing assistance, SESA would require agencies generally to base rents on actual income in the previous year. This would give tenants an incentive to increase their earnings, since such an increase would not affect their rent for as long as a year. It also would simplify administration, both by making it easier for agencies and owners to use tax forms and other year-end documentation to verify income and by reducing the need for mid-year rent adjustments for tenants whose earnings change during the year.

- Allow housing agencies to use income data gathered by other programs. One of SESA's provisions would allow state and local housing agencies and owners to rely on income determinations carried out under SNAP (formerly food stamps) and other federal means-tested programs, without separate verification. Currently, housing agencies and owners must determine and verify income independently, even though this duplicates work already being carried out by other agencies. Allowing housing agencies to rely on income determinations made by SNAP agencies would ease their administrative burdens considerably, since a large portion of housing assistance recipients also receive SNAP benefits.

The SESA provision, however, does not require state SNAP agencies to provide the needed data, and it is unlikely that many states would do so voluntarily. Congress could address this by adding to SESA a provision included in the December 2010 draft of SEVRA, which required SNAP agencies to make available to housing agencies income data for families participating in both programs.

SESA Would Raise Rent Revenues Modestly, But Protect Families from Sharp Increases

No comprehensive analysis has been released on the impact of the current SESA discussion draft on tenant rent payments. A Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimate circulated as part of a discussion draft at the end of the last Congress estimated that similar provisions would raise total tenant rent payments by $60 million annually during the first four years after they go into effect. This would amount to an average rent increase of less than half a percent for each household receiving housing assistance under the three major programs.

Some individual tenants would face higher or lower monthly rents under SESA, but the impact would generally be modest. For example, when the change in the medical deduction is offset by the increase in the standard deduction from $400 to $675, an elderly person or person with a disability with an annual income of $8,000 who currently receives a large deduction for medical expenses would face a maximum monthly rent increase of $7.13. The maximum rent reduction for a person who has few or no unreimbursed medical expenses (or has such expenses but does not currently receive the deduction to which he or she is entitled) would be $6.88 a month.

Rent Demonstration Could Be Useful, but Restrictions Should Be Tightened

SESA would also authorize HUD to conduct a limited demonstration of alternative rent policies. Such a demonstration is potentially beneficial. Today's rent rules generally work well, providing sufficient help to enable the neediest families to afford housing while not giving higher-income families more subsidy than they need. In addition, the current system maintains largely identical rules across programs and localities, making it easier for voucher holders to move from one community to another (for example to pursue a job opportunity), easier for private-sector owners and investors to participate in multiple programs and operate in multiple jurisdictions, and easier for HUD to provide effective oversight.

Most major changes — and particularly those that would result in sharply higher or lower subsidies for certain families — would carry substantial risks and tradeoffs. It is possible, however, that some substantial changes would have significant benefits that would justify enacting them on the federal level. For example, a policy of disregarding some percentage of earned income would carry added costs, but might encourage sufficient increases in earnings to offset a sizable share of the cost and justify the change. A demonstration could offer an opportunity to rigorously test policy alternatives to determine their costs and benefits relative to the current rules.

The SESA rent demonstration is strongly preferable to an alternative rent policy in H.R. 3045, which would have allowed all housing agencies to implement certain alternative rent policies in public housing. That policy would have resulted in an unwieldy patchwork of local rent rules and risked substantially raising federal costs.

However, the SESA rent demonstration can and should be strengthened in important ways. HUD's 2012 budget, which proposed a similar demonstration, provides HUD broader flexibility to identify promising policies and limits the demonstration to five years to avoid allowing wasteful or harmful policies to remain in place indefinitely. Both of these improvements should be adopted. In addition, bill language should explicitly require a rigorous, experimental evaluation and clarify that the "limited" number of families that can be subject to alternative policies should be no more than the number needed to yield statistically valid results.

Streamlining Housing Inspection Rules to Encourage Participation by Private Owners

The voucher program requires that vouchers be used only in houses or apartments that meet federal quality standards. SESA would allow agencies to make modest changes in the inspection process used to ensure that units meet those standards. The changes would ease burdens on agencies and encourage landlords to rent apartments to voucher holders. Most significantly, SESA would allow agencies to inspect apartments every two years instead of annually.

In addition, to eliminate inspection-related delays, the bill would allow agencies to (1) rely on recent inspections performed for other federal housing programs, and (2) make initial subsidy payments to owners even if the unit does not pass the initial inspection, as long as the failure resulted from non-life-threatening conditions. Defects would have to be corrected within 30 days of initial occupancy for the payments to continue. These provisions would encourage owners to participate in the voucher program by minimizing any financial loss due to inspection delays. They also would enable voucher holders, who in some cases are homeless or experience other severe hardship, to move into the unit more quickly than under current rules.

Today, when an inspection of a unit occupied by a voucher holder finds a violation, the housing agency is permitted to temporarily halt subsidy payments if the owner fails to address the violation in a timely manner, and ultimately terminate the subsidy if the defects are not adequately repaired. SESA would retain this authority and establish a series of requirements regarding the rights of tenants and other aspects of subsidy abatement and termination. In the versions of SEVRA considered in the last Congress, housing agencies were required to provide assistance to help tenants find a new unit and relocate if the subsidy to their unit is terminated because of an inspection violation. SESA would make this assistance optional. It will be important that Congress restore this key requirement as SESA moves forward.

Easing Income Targeting Rules to Help More Working-Poor Families

Currently, 75 percent of vouchers and 40 percent of project-based Section 8 and public housing units must be allocated to households with incomes at or below 30 percent of the median income in the local area at the time they enter the program. SESA would adjust these criteria to require that those vouchers and units be allocated to households with incomes at or below 30 percent of local median income or the federal poverty line, whichever is higher. Neither this revised requirement nor current law restricts a family's income after it is admitted. [5]

This change would give housing agencies greater flexibility to target working-poor families. Some agencies in low-income areas have expressed concern that the current targeting criteria prevent them from assisting these families. About 770,000 additional working-poor families would be eligible for priority admission based on the SESA change.[6] At the same time, the change would maintain the emphasis on assistance for the poor. The reduction in subsidy needs that would result from easing targeting rules is the main source of the more than $700 million in net savings CBO estimated SEVRA would generate over five years.

Facilitating Use of Project-Based Vouchers

The current draft of SESA omits an important set of provisions from H.R. 3045 that would have made it easier for a housing agency to enter into agreements with owners for a share of its vouchers to be used at a particular housing development. Through such "project-basing," agencies can partner with social service agencies to provide supportive housing to formerly homeless people or support development of mixed-income housing in low-poverty neighborhoods with strong educational or employment opportunities but tight rental markets.

Residents of units with project-based voucher assistance have the right to move with a voucher after one year, using the next voucher that becomes available when another family leaves the program. (When this occurs, a voucher remains attached to the housing development; the family moving out of the development receives a separate voucher.) This "resident choice" feature and other policies make the project-based voucher option significantly different from earlier programs that provided project-based assistance.

SESA includes only one improvement to the project-based voucher program: an option for agencies to commit to project-based voucher contracts with a term of 20 years, rather than the 15-year maximum permitted today. This change would parallel the policy that now exists for project-based section 8 contracts administered by HUD's Office of Multifamily Housing.

H.R. 3045 included a number of other provisions to facilitate the use of the project-based voucher option for supportive housing and in areas where tenant-based vouchers are difficult to use. For example, the bill permitted owners to establish and maintain site-based waiting lists, subject to civil rights and other requirements, and protected tenants from eviction except for good cause. It also allowed an agency to provide project-based assistance to 25 percent of the units in a project or 25 units in the project, whichever is greater, and in areas in which vouchers are difficult to use (as defined by HUD) or the poverty rate is 20 percent or less, it would permit 40 percent of the units in a project to have project-based voucher assistance. These policy changes would give PHAs additional tools to increase the effectiveness of the voucher program in rural and suburban areas, where rentals are frequently scarce and properties tend to be small, and also in low-poverty areas in all types of locations. The final bill should include these provisions.

It also would be worthwhile to include a compromise policy change included in the December 1 discussion draft of SEVRA, which would have increased the percentage of an agency's vouchers that can be used for project-basing from 20 percent to 25 percent, if the additional 5 percent authority is used to expand the affordable units available to homeless individuals and families or in areas where vouchers are difficult to use, or to provide supportive housing to people with disabilities.

Improving Fair Market Rent Determinations

The SESA discussion draft would permit modest but beneficial changes to the process HUD uses to establish Fair Market Rents (FMRs). FMRs, which are set for each metropolitan area and rural county, are used to cap voucher subsidies and for other purposes in a range of housing programs. The bill would eliminate a burdensome requirement that HUD publish proposed FMRs for comment, and instead only require that HUD request comments on significant changes in the methodology used to set FMRs.

This change would be much more helpful, however, if Congress also revised a statutory requirement that final FMRs be published and go into effect on October 1 each year, by moving that date back to April 1. This would enable HUD to more promptly set FMRs based on the most recent rent data from the American Community Survey, which becomes available to HUD close to the beginning of the calendar year . For example, HUD's fiscal year 2012 FMRs, which will be finalized and go into effect on October 1, 2011, will use ACS rent data from calendar year 2009 — a period that ended 21 months earlier. But HUD received that ACS data in early 2011 and could have processed and issued final FMRs in April 2011 if it were not statutorily required to adjust the FMRs for each fiscal year. (The federal fiscal year begins October 1.) At that point, the data would have been six months more current and substantially more likely to reflect actual rents.

HUD's 2012 budget proposed that the statutory deadline be eliminated entirely, but this would risk delays in the release of FMRs. Similarly, it would be worthwhile to add a statutory deadline for HUD's release of income limits used in housing assistance programs. There currently is no such deadline, and there have been substantial delays in release of the limits in some years. Because HUD uses FMRs to make certain adjustments to income limits, the deadline for income limits should be about a month after the FMRs are required to be published, so that the income limits can rely on the most up-to-date FMR levels.

In addition, SESA omits a beneficial provision of earlier versions of SEVRA that would have required HUD to establish FMRs for smaller areas than it does today. HUD has sufficient authority to take this measure on its own, however, and has solicited applications from housing agencies to participate in a demonstration testing the establishment of FMRs for individual zip codes. As a result, it appears likely that this important change will move forward without legislative action.

Using smaller FMR areas would result in more accurate FMRs, since the current metropolitan-level FMRs are too high or too low in many individual neighborhoods. As a result, this change could improve the cost effectiveness of the voucher program by preventing vouchers from overpaying in low-rent areas, while also giving voucher holders better access to low-poverty areas with good schools and low crime but somewhat higher rents. Initially the change could generate substantial savings, since voucher holders today are disproportionately located in lower rent areas where FMRs would fall, but that effect would likely fade over time.

Strengthening the Family Self-Sufficiency Program

The Family Self-Sufficiency (FSS) program encourages work and saving among voucher holders and public housing residents through employment counseling and financial incentives. Unfortunately, residents of units assisted through a different HUD funding stream — project-based Section 8 contracts — are ineligible for the program. SESA corrects this omission, enabling families receiving any type of Section 8 assistance as well as public housing residents to benefit from FSS. Offering participation in the FSS program to assisted tenants would be optional for property owners. Generally, such tenants would participate in an FSS program operated by a public housing agency, if one is available that will admit the families. Owners of properties with project-based Section 8 contracts may use funds in their HUD-required "residual receipts accounts" to operate an FSS program independently if it serves at least 25 participants.

SESA also makes a number of other changes in the policies that apply to any FSS program, largely to eliminate differences in current law between FSS policies that apply to families residing in public housing and those receiving housing voucher assistance, as well as to update some policy details. Uniform policies will simplify administration of FSS for housing agencies and HUD. To realize the goal of uniformity, however, the bill needs to go one step further and eliminate the current statutory requirements for separate funding for agency staff to counsel participants and coordinate employment services, depending on whether the participants are assisted under the public housing or voucher program. Establishing a predictable formula for allocating funding to support these specialized agency staff, as the bill would do, is important. But the language of the new formula should be modified so that a single funding stream can support FSS coordinators staffing programs serving any eligible family.

Protection Against Arbitrary Screening of Housing Assistance Recipients

Housing agencies and owners must screen housing assistance applicants based on several federally required criteria, and have the option to establish additional screening criteria. SESA would make several changes to the screening process for the housing voucher program, including limiting optional screening criteria to those directly related to the family's ability to meet the obligations of the lease and requiring housing agencies to consider mitigating factors before denying assistance. These important improvements, for example, would prevent a family from being denied assistance if it has a good record of paying rent on time but has a poor credit history for other reasons (as many poor families do). They would make it more likely that housing vouchers would go to homeless people and others with an urgent need for assistance who might otherwise face a high risk of being denied for arbitrary reasons.

Unfortunately, the current SESA draft drops a provision of some versions of SEVRA that would have made similar (and equally important) changes in the public housing and project-based Section 8 programs. Congress could extend the changes to those programs by restoring the omitted provisions or simply by giving HUD authority to establish common requirements for all rental assistance programs.

SESA also would add an important protection for families being shifted from assistance under the public housing or HUD multifamily programs to housing vouchers due to the elimination of the former project-based assistance for the properties in which they reside. The bill recognizes that such families are not new to HUD assistance and should be considered as continuing participants rather than new applicants subject to initial screening. This change also will reduce administrative burdens for PHAs administering the new tenant protection vouchers.[7]

Making Vouchers More Effective in Special Circumstances

The draft SESA bill omits two worthwhile provisions included in the versions of SEVRA considered by the House in the last Congress that would enable the voucher program to work more effectively in two special circumstances: when people with disabilities need to rent a somewhat more expensive unit because its special features are needed to accommodate their disabilities, and when a family with a voucher wants to use it to reside in manufactured housing (mobile homes). Current law does not permit the flexibility these situations require. The number of people affected is so few that the cost impacts would be de minimis.

Providing Local Flexibility to Adjust Voucher Payments to Accommodate The Special Needs of People with Disabilities

Housing agencies today can permit people with disabilities to use vouchers to rent more expensive units than is permitted for other families, if this is necessary to accommodate their disability. But if this requires a subsidy cap (or "payment standard") above 110 percent of the local Fair Market Rent, the agency must obtain special approval from HUD. A provision in SEVRA would reduce the need for this cumbersome process by allowing agencies to provide such exceptions up to 120 percent of the FMR without approval from HUD. Accessible units are often more expensive than the typical units in a given area, either because they require added investments by owners or simply because few such units exist. As a result, prompt access to exception payment standards like those permitted under the SEVRA provision can be crucial to the ability of people with disabilities to use vouchers.

Allowing Vouchers to Be Used More Easily in Manufactured Housing

SESA drops a beneficial SEVRA provision that would allow vouchers to be used to cover loan payments, insurance payments, and other periodic costs of buying a manufactured home, in addition to the cost of renting a space on which to place the home. The combined payments would, however, be subject to the same maximum subsidy limits that apply to other vouchers. Currently, vouchers can be used to cover the full range of periodic homeownership costs for the purchase of a traditional home or a manufactured home set on land also purchased by the family. But if a family rents the space for a manufactured home, which is common in some states, the voucher subsidy is limited to about 40 percent of the assistance it could otherwise provide, and can only cover the space rental costs and not the costs of purchasing the home.

The SEVRA provision would allow vouchers to be used effectively in a segment of the housing market that in some areas is the most readily available source of affordable housing — and that for many families offers the most realistic avenue to homeownership. Congress should add this provision to SESA as the bill moves forward.

MTW Expansion Should Not Be Added to SESA

The current SESA draft omits a provision contained in some earlier House versions of the legislation that would have expanded sharply the number of agencies that can participate in HUD's Moving-to-Work (MTW) demonstration and renamed the demonstration the "Housing Innovation Program" (HIP). MTW allows HUD to waive federal statutes and regulations and establish special funding arrangements for agencies administering public housing and vouchers. The demonstration already has grown substantially in recent years, from 25 agencies in 2008 to 35 today. There is no persuasive rationale for expanding MTW further.

A number of well-run, innovative agencies participate in MTW today, and these agencies have implemented some promising strategies. MTW is poorly designed to achieve its main goals, however, such as testing policies to promote self-sufficiency or streamlining program rules. Moreover, MTW agencies serve far fewer families per dollar of federal funding than other agencies, on average, and their relatively rich funding arrangements shift resources away from non-MTW agencies. These harmful effects could worsen if the demonstration were expanded.

MTW Has Not Been Effective in Testing Policies to Promote Work

Despite its name, MTW is not focused primarily on promoting work and has been ineffective in testing policies to achieve this goal. MTW agencies have implemented policies such as employment services, time limits, work requirements, and changes to rent rules. While it is possible that some of these policies promote work, there is no reliable evidence of this.

This is largely because MTW was not designed as an experimental demonstration, in which randomly selected families receive housing assistance under alternative policies and are compared to otherwise-similar families who receive assistance under regular program rules. Such a design would require agencies to take on the added task of administering two sets of rules. But it is a standard feature of successful policy demonstrations, because otherwise it is very difficult to determine the actual effects of experimental policies.

For example, MTW agencies are permitted to establish "flat rents" that are the same regardless of a tenant's income. Such rents are meant to encourage work, but could also increase hardship and even homelessness (because the poorest families may be charged more than they can afford) or waste money (because higher-income families receive larger subsidies than they need). Without an experimental evaluation, however, it is difficult to determine whether subsequent trends in employment, hardship, or costs stemmed from the flat rent policy or from other factors. such as local economic conditions or changes in the makeup of the agency's caseload.

In addition, MTW is an inefficient way to test policies, due to several flaws that would be difficult to fix without radically altering the demonstration. It allows agencies to expose all assistance recipients to untested policies rather than only the small share needed to determine the policies' effects. Moreover, HUD has permitted agencies to extend the application of experimental policies indefinitely whether or not they have proven effective. In addition, MTW institutes other harmful features that are often unrelated to the policies being tested, such as the costly funding arrangements described below.

If Congress wishes to identify which self-sufficiency policies work and should be scaled up, it could do so most effectively by creating a targeted, temporary, and rigorously evaluated demonstration — not by expanding MTW, which has failed for over a decade to generate meaningful findings about many of the key policies it has tested. The rent demonstration currently in SESA offers an opportunity to pursue this more promising approach, although as noted above, several changes should be made to strengthen that demonstration.

Administrative Streamlining Should Be Applied Nationally, Not to Select Agencies

Proponents of expansion argue that the flexibility MTW provides can enable agencies to streamline their programs and operate more efficiently and effectively. MTW, however, is not an effective mechanism to achieve streamlining. Where added streamlining and flexibility are warranted, they should be provided to all agencies (as SESA would do in areas such as rent determinations and inspections) or, in certain circumstances, to all high-performing agencies.

MTW, by contrast, gives a select group of agencies far more flexibility than is desirable to operate outside of the rules Congress established to ensure that housing assistance funds are spent effectively. For example, under MTW HUD can waive statutory restrictions on project-basing and permit agencies to raise the share of their vouchers they project-base far above the level allowed today (and also far above the modest increases permitted for non-MTW agencies under the SEVRA bills considered in the last Congress). HUD has also permitted many MTW agencies to eliminate the "resident choice" feature of the project-based voucher program, depriving families of the ability to move with rental assistance. Through such waivers, MTW has become a back-door way to overturn the decades-long congressional commitment to prohibit additional housing with rental assistance attached to the properties (except for new supportive housing for the elderly and people with disabilities) unless tenants retain an option to move with ongoing rental assistance.

In addition, extending broad flexibility to a large number of agencies in some areas — such as rent policy — could make housing assistance less efficient by fostering a complex patchwork of local rules. This would make it more difficult for HUD to provide adequate oversight, for private owners and lenders to navigate federal programs, and for families to use vouchers to move from one community to another.

MTW Funding Shifts Undercut Cost Effectiveness of Housing Assistance

Unlike other agencies, MTW agencies are permitted to shift funds appropriated for vouchers to other uses. In 2010, agencies shifted approximately $400 million to other purposes or left the funds unspent, leaving close to 40,000 funded vouchers idle that could have been used to assist needy families. [8] A non-MTW agency that left vouchers unused in this manner would face a sharp cut in funding in the following year, because its voucher subsidy and administrative funding are based on actual subsidy costs and the number of families it assists. But MTW formulas generally eliminate these incentives, allowing agencies to leave vouchers unused without adverse consequences.

MTW agencies have shifted voucher funds to a variety of purposes, including building or rehabilitating public or other affordable housing and contracts with local organizations to provide services. These expenditures may have benefits, but they do not extend housing assistance to additional families — or at least not enough to offset the vouchers left unused. In 2009, MTW agencies provided housing assistance to about 9 families per $100,000 in public housing and voucher funding, compared to 15 families at non-MTW agencies.[9]

Special MTW Funding Arrangements Have Diverted Funds from Other Agencies

The special funding arrangements provided to MTW agencies are, on average, far more generous than those provided to non-MTW agencies. MTW agencies received 32 percent more voucher funding per authorized voucher in 2010 than other agencies. In 2009, when Congress enacted a funding policy (a "reserve offset") that reduced funding for many non-MTW agencies, MTW agencies on average received 52 percent more funding per authorized voucher. Similarly, ten MTW agencies received public housing operating funding in 2010 under special formulas, which on average provided 89 percent more funding per unit than other agencies received.

This added funding has sometimes come at the expense of other agencies, because in years when appropriations fall short of the full amount for which agencies are eligible, HUD reduces funding for all agencies on a prorated basis. In 2010, for example, HUD reduced voucher funding by 0.5 percent, forcing agencies to assist thousands fewer families than they could have with full funding. If MTW agencies had been subject to the same formula as other agencies, the voucher appropriation would have been adequate to cover the full amount for which all agencies were eligible, and the proration would not have been necessary. Similarly, without the extra cost of providing voucher funding to MTW agencies, the proration of renewal funding by more than 1 percent in 2011 likely would not have been necessary, and the steep cut in administrative fees for all agencies would have been reduced.

Conclusion

SESA would build on the voucher program's many strengths through a series of measured, targeted improvements that, taken together, would deliver important benefits to housing agencies, private owners, and low-income families. Moreover, because several of the bill's provisions extend beyond the voucher program, it also would improve the public housing and project-based Section 8 programs.

It is important that Congress not only act on SESA, but do so expeditiously. The need for housing assistance is unusually high today, with elevated levels of homelessness and poverty and widespread foreclosures. Yet Congress appears unlikely to expand resource for housing assistance, and is likely to consider substantial cuts — on top of the sharp reductions enacted in 2011 to voucher administrative fees, public housing capital grants, and other housing programs. At this time, the nation needs its housing assistance programs to be as efficient and effective as possible, and the measures in SESA would take major steps toward that goal. The bill's provisions have been fully vetted through deliberations in the past three congressional sessions. It is urgent to enact SESA before the end of 2011, so that its changes can apply to the 2012 funding year.

End Notes

[1] A detailed side-by-side comparison between SESA's provisions and current law is available at https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/SEVRA-SESA-current%2520law%2520comparison.pdf .

[2] From 2004 – 2006 about 150,000 vouchers that agencies were authorized to administer were taken out of use. Such losses were likely due in part to the instability of the funding policy as well as funding shortfalls, but the lack of any adjustment to renewal funding for 2006 based on actual leasing and costs in 2005 likely also played a significant role. See Douglas Rice and Barbara Sard, " https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/2-24-09hous.pdf," February 24, 2009, pp. 13-14. Until HUD extended the policy to all agencies participating in the Moving to Work Demonstration in 2008, only a portion of the agencies received voucher funding without regard to utilization. Many of the block-grant-funded agencies had far lower voucher utilization rates than other agencies.

[3] Many fixed-income benefits, such as Social Security and SSI, typically increase annually due to cost-of-living adjustments. To avoid a loss of revenue from this streamlined option, agencies would be required to assume that in the intervening two years these tenants' incomes rose by a rate of inflation specified by the HUD Secretary.

[4] HUD's most recent rental assistance quality control report showed that the medical deduction was the third largest cause of rent payment errors, in terms of the number of households in error: 19 percent of households that paid too much or too little rent had a medical deduction-related error. In contrast, only 2 percent of all households experienced payment error in the application of the elderly/disabled standard allowance and 3 percent in the application of the dependent allowance. ICF Macro International, "Quality Control for Rental Assistance Subsidies Determinations," October 16, 2009, Exhibits IV-12 and IV-15.

[5] A separate provision of SESA would prohibit families from continuing to receive assistance if their income rises to a much higher level (generally above 80 percent of local median income). Currently, there is no income limitation after admission. As a practical matter, however, this new policy will have limited effect, since owners and agencies can opt not to enforce it in project-based Section 8 and public housing. And families with incomes above 80 percent of median in most areas no longer qualify for assistance under the voucher program because 30 percent of their adjusted income — their required contribution — exceeds the maximum rent a voucher can cover.

[6] This estimate is based on 2008 data.

[7] The new provision, included in section 11(a)(5) of the draft bill, requires technical corrections to the references to types of tenant protection vouchers, as the cross-citations on page 65, lines 4 and 8 are not included in the bill.

[8] The data on MTW expenditures and families served discussed here cover the 30 agencies that participated in MTW throughout 2009 and 2010. Three additional agencies began participating in the demonstration between August 2010 and January 2011, and two more have been selected and are in the process of negotiating MTW agreements with HUD. Estimates of funds not spent on vouchers are based on HUD data on the amount of voucher subsidy funds provided to MTW agencies and the amount that the agencies spent on voucher subsidies. Some MTW agencies receive voucher administrative funding (which for non-MTW agencies is provided through a separate budget account) and subsidy renewal funds together in a single funding stream. In these cases, CBPP estimated the amount that was intended as administrative funding and deducted it from the agency's funding level before calculating the amount of funds unspent. Many MTW agencies receive more funds than they need to support all of their authorized vouchers, so only some 30,000 of these unused vouchers fall within agencies' authorized levels. MTW agencies are permitted to use vouchers above their authorized level, however, so they could have issued the full number of vouchers that their funding supported had they opted to do so.

[9] 2009 is the last year for which sufficient data are available to make this comparison. The calculations include families listed in HUD data or agency reports as receiving assistance during calendar year 2009 (or the most closely overlapping period available) through vouchers, public housing, or other comparable housing assistance provided through MTW-funded agency initiatives. The funding levels are for calendar year 2009 and include voucher subsidy funds, administrative fees, public housing operating funds and regular public housing capital formula grants, but not HOPE VI grants, replacement housing factor grants, or capital funds provided through the 2009 economic recovery package.