- Home

- Strategies To Address The State Tax Vola...

Strategies to Address the State Tax Volatility Problem

Eliminating the State Income Tax Not a Solution

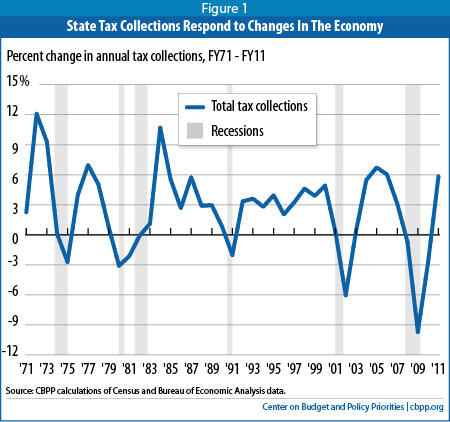

State revenues plummet in recessions, just when states can least afford the loss. Some proposals to address this flaw in state tax systems would change the systems’ structure — for instance, by replacing state personal income taxes with sales taxes — but wouldn’t solve the problem and would exacerbate others in state tax systems. States have to balance their annual budgets so they cannot just run up debt during recessions, but they could better address revenue volatility with such strategies as stronger reserve funds and better mechanisms for managing budget surpluses.

Revamping state tax structures to minimize income tax is a poor solution for the volatility problem for the following reasons:

- Virtually all state taxes are volatile, albeit to varying degrees. Most major state taxes, including the sales tax, are subject to ups and downs with the economy. Indeed, under some circumstances, sales taxes can decline faster in recessions than income taxes.

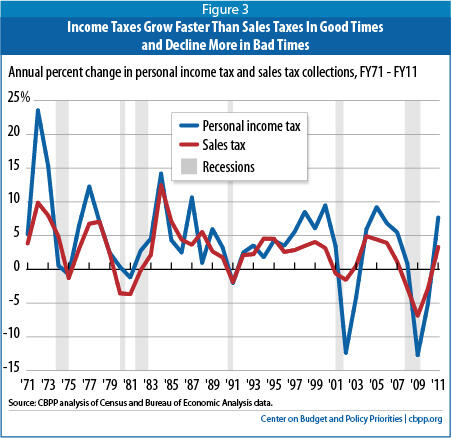

- While income taxes typically fall more steeply than sales taxes when the economy enters a recession, the reverse is also true: income taxes rise more rapidly than sales taxes during periods of economic growth. Taking both periods of growth and decline together, income taxes — but not sales taxes — increase enough to fund normal expenditure growth and meet the evolving needs of residents and businesses.

This means that if a state repealed its income tax near the beginning of a period of economic growth, it would miss out on several years in which the income tax was outpacing the sales tax. The effect would be analogous to disinvesting in the stock market at the beginning of a period of market appreciation to avoid the market’s inevitable ups and downs.

A better approach is a thoughtful combination of revenue diversification, careful planning, and the use of emergency federal aid. A state can reduce the volatility of its overall tax collections and improve its fiscal health by adopting better budget practices. Adopting some or all of the following practices now — during an economic recovery — is the best way for states to be prepared for the next recession.

- States should have stronger reserve funds, such as rainy day funds, that they can use to smooth out the ups and downs of tax collections when a recession hits. States should use spikes in tax collections to boost those balances. Income tax (or other tax) revenues that rise rapidly in good times can be deposited in a rainy day fund for use during economic downturns.

- States should avoid new long-term spending or tax-cut commitments that are unfunded or that are funded in the short term through unsustainable revenue spikes. Instead, when a tax such as an income tax is growing at above-normal rates, the revenue — if it is to be spent rather than placed in reserve — should be set aside for expenditures that are one-time in nature, such as infrastructure, early retirement of debt, improved pension funding, or shoring up unemployment insurance trust funds. This avoids the problem of creating long-term problems by cutting taxes permanently or creating new programs with uncertain revenues. Further, it gives states the option of shifting back to greater use of debt financing during downturns.

- States should rely on a variety of taxes that each respond differently to economic changes to further smooth out total tax collections without sacrificing the advantages of the income tax, such as its progressivity. For example, the growing number of states with oil and gas production could increase their reliance on severance taxes in conjunction with other measures to address tax volatility. States can also insure a balanced mix of revenue by avoiding measures that limit local governments’ ability to levy adequate property taxes.

- States should be willing to use temporary tax changes to smooth out short-term dips or spikes in collections. In times of above-average economic growth, tax rebates should be considered as an alternative to permanent cuts. Conversely, during recessions, income or sales tax rates can be temporarily increased. This type of tax structure can allow a state to have lower permanent rates on all taxes in times of normal growth.

States should also have the ability to access emergency federal aid during recessions to help balance their budgets. In each of the last two recessions, and particularly the severe recession of 2007-09, emergency federal aid to states helped avert a substantial amount of spending cuts and tax increases. It also helped strengthen the U.S. economy, in part by reducing the number of people out of work. Since states will never be able completely eliminate or offset the effects of economic cycles on their budgets, the federal government will continue to play an important role in managing these declines by providing additional aid to states and their residents. States should consider working with the federal government to make such emergency aid an automatic response to recessions.

Tax Volatility Is a Weak Argument for Income Tax Cuts or Repeal

The precipitous decline in state revenues during the 2007-09 recession — which resulted in large budget shortfalls that states ultimately resolved largely through a mix of tax increases and cuts in public services like education and health care — has understandably raised the question of whether different tax structures would have helped to avert those shortfalls.[1] Some observers have pointed to the personal income tax as the primary reason for the recessionary ups and downs in state tax collections. In turn, some income tax opponents have used this observation to argue that states should not have income taxes or should scale them back considerably.[2] But these would be poor solutions. Income taxes are not the only volatile tax, and they provide other important benefits to tax systems that outweigh their reduction in revenue during a recession.

All Taxes Are Sensitive to Business Cycles

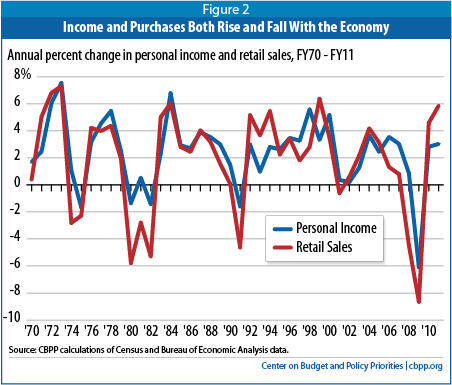

In general, incomes and retail sales — the underlying bases of state income and sales taxes — have grown or fallen at roughly similar rates in recent years. (See Figure 2 which shows annual changes in personal income and retail sales.) This suggests that an income tax that was a flat percentage of all personal income would likely rise or fall in any given year at about the same rate as a sales tax that covered all sales. But, for a variety of reasons, actual state income taxes and sales taxes are not structured that way. As a result, they respond somewhat differently to economic changes.

The typical state sales tax, on the other hand, excludes most purchases of services and is less responsive to economic growth than an income tax.[5] (See Figure 3.) State sales taxes generally grow less than 1 percent for each 1 percent increase in income. This is largely because purchases of services have made up a growing share of total consumption for many years and the rise of largely untaxed sales over the Internet. Other state taxes and fees — including gas taxes, alcohol taxes, tobacco taxes, and driver’s license fees — grow considerably more slowly than the economy. This is because these types of taxes are generally levied per piece (gallon or cigarette, for example) and do not respond to inflation.

This had a disproportionate effect on revenue collections in a handful of states that rely heavily on the personal income tax, including large states like California and New York. As a result, these states’ revenues rose rapidly in the late 1990s and mid-2000s and fell quickly with the market, dragging down overall national collections when the market plummeted.

Still, revenues in states without an income tax also were affected by the recession. Revenue collections in Florida and Nevada — two states with no income tax — were among the hardest-hit in the last recession.[6]

States Need a Mix of Revenues, Including Progressive Income Taxes,

to Support Regular Program Growth

The primary purpose of state taxes is to fund education, health care, and other government services adequately and consistently. When a state’s normal revenue growth is insufficient to finance normal expenditure growth year after year, the state will face gaps between estimated revenues and expenditures each year. Every state except Vermont is required (by constitution or statute) to balance its budget, thus they must address the gaps that arise by either by raising taxes, cutting spending, or some combination of these.

Even if no programs or services are improved, the costs of providing services generally rise from year to year because inflation pushes up the costs of purchased goods and services, states must provide their employees with reasonable increases in wages and benefits to compete with the private sector, and the populations that require services may be growing.

| Table 1 State Sales Tax Rates Have Increased While Top Income Tax Rates Have Declined | ||

| Year | Median Sales Tax Rate | Median Top Income Tax Rate |

| 1970 | 3.25% | 6.50% |

| 1980 | 4.00% | 7.50% |

| 1990 | 5.00% | 6.97% |

| 2000 | 5.00% | 6.75% |

| 2010 | 6.00% | 6.50% |

| Sources: ACIR, Significant Features of Fiscal Federalism; Council of State Governments, Book of the States; Tax Foundation; Bruce, Fox, State And Local Sales Tax Revenue Losses From E-Commerce: Updated Estimates | ||

In addition, new circumstances frequently arise that require an increase in spending, such as the pressure throughout the country for smaller public school classes or from businesses for more sophisticated laboratories and other training facilities at public colleges and universities. And states sometimes face increased costs over which they have little control, such as natural disasters and new federal mandates ? as when Congress requires increased testing of school students or increased spending on anti-terrorist activities — without providing additional federal funds.

As discussed in the previous section, sales tax revenue tends to lag income growth. As a result, states have often turned to sales tax rate increases to maintain programs. The sales tax rate in the typical state is almost twice as high now as it was in 1970. (See Table 1.) These rate increases were in large part necessary to offset the shift in consumption from goods to largely untaxed services and the rise of often-untaxed sales over the Internet.

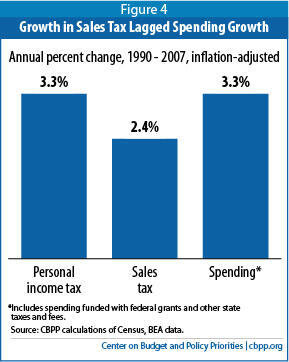

Even with these rate increases, sales tax revenue has not kept up with state spending growth in recent decades. From 1990 to 2007 (just prior to the last recession), state spending grew by 3.3 percent per year, after inflation, while sales tax collections grew by only 2.4 percent. (See Figure 4.) Income taxes, on the other hand, have kept pace with growing costs even though income tax rates have declined since 1980.

Including an income tax in the mix of taxes in a state is somewhat like having a balanced portfolio of investments. That portfolio would normally include some riskier components that have the potential for more growth over the long-term, such as stocks. Similarly, state personal income taxes are subject to wider swings up and down but over the long-term grow more than other state taxes. [7] The relatively strong growth of income tax revenue allows states to deliver public services at a level adequate to meet the needs of state residents and the challenges of an ever-evolving economy, even as revenue from sales taxes and other sources grows more slowly than needed.

Replacing the Income Tax With a Sales Tax Would Reduce

Growth Without Eliminating Volatility

The reason is that by repealing a personal income tax, a state would lose all the benefit of revenue growth during economic expansions. Even if the personal income tax falls faster than the sales tax when the recession hits, the decline will be from a higher level, so the personal income tax will still raise more money than the sales tax.

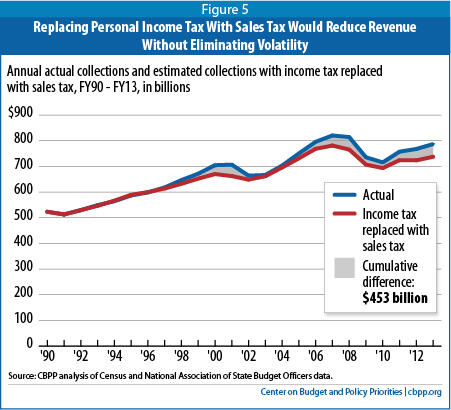

To illustrate this point, Figure 5 models the replacement of the income tax with a sales tax by applying the annual rate of growth in sales tax collections to the amount of revenue collected in income taxes in total starting in 1990. By 1997 total collections would have been less each year than if state relied on both sales taxes and personal income taxes, as the figure shows. Cumulatively, from 1990 to 2012, states would have collected more than $400 billion less in revenue. In addition, tax collections would have remained volatile with significant declines when the economy contracted.

Eliminating the Income Tax Would Exacerbate the Problem of State Tax Regressivity

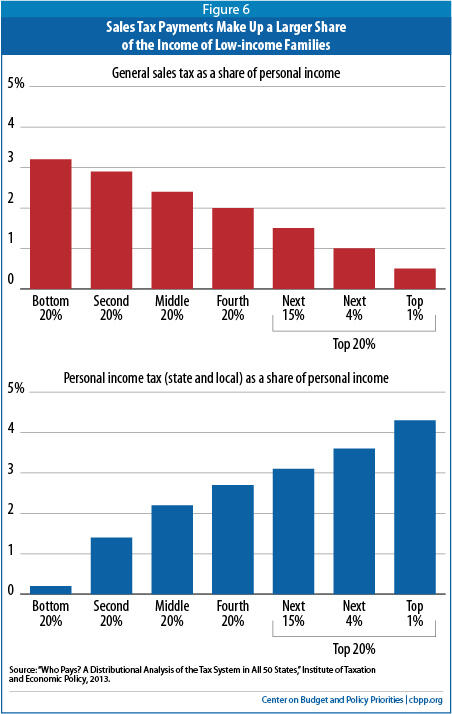

Most states’ income taxes are at least somewhat progressive; that is, income tax payments represent a smaller share of income for low-income families than for high-income families. The other primary source of state tax revenue, the sales tax, is regressive, consuming a larger share of the income of low-income families than of high-income families. (See Figure 6.) On average, the richest 1 percent of taxpayers pay 4.3 percent of their income in personal income taxes, while the poorest 20 percent pay only 0.2 percent of their income, according to a recent study.[9] In contrast, the richest taxpayers pay only 0.5 percent of their income in general sales taxes compared to 3.2 percent for the poorest fifth.

States that rely on non-income taxes tend to have higher overall taxes on the poor than do other states. Most of the states without income taxes instead rely heavily on the sales tax, which renders their tax systems very burdensome for low-income families. Thus, eliminating the income tax would cut taxes for the wealthiest taxpayers and, if the replacement were revenue-neutral (designed to raise the same amount of total revenue), would raise taxes for the rest.

This shift in taxes from the wealthiest to those lower on the income scale would come at a time when income growth in the United States is concentrated at the top of the income scale. The incomes of the top 1 percent of households grew by 155 percent between 1970 and 2009, while those of the middle 60 percent grew by only 37 percent. Thus, if a state eliminated the income tax, it would provide a tax break to the taxpayers who need it least.

Ways to Address Volatility While Maintaining a Graduated-Rate Income Tax

The problems associated with the ups and downs of state tax systems can be addressed without eliminating or flattening state income taxes. These include changes to budget procedures such as maintaining a larger rainy day reserve or using extra revenues from good economic times for one-time expenditures as well as changes to state tax structures.

Budget Management Techniques

Rainy Day Funds. Experience shows that the rainy day funds that already exist in most states can be an effective way to counteract volatility in tax collections. States with rainy day funds were able to avert over $20 billion in cuts to services, tax increases, or both in the recession of the early 2000s. And they avoided still more cuts in the most recent recession.

But, rainy day funds would have been even more effective if they had been larger. States maintained average reserves of some 10 to 11 percent entering both of the recessions of the last decade. The experience of the last several years indicates that states should aim for reserves higher than the levels reached prior to recent recessions. A 1999 Center analysis found that states would need reserves equal to 18 percent of spending, on average, to weather a simulated recession without substantially cutting spending or raising taxes.[10] While reserves at this level would only be enough to fully cover the shortfalls resulting from a relatively short and mild recession such as that of the early 1990s, they would go considerably further toward preserving needed programs than the reserves that most states have typically accrued under current practices. For example, in the 2001 recession, states’ rainy day funds and unreserved balances equaled only $60 billion prior to the downturn, while states faced a total of $240 billion in budget gaps over the course of the recession and its recovery.

Periods of rapid revenue growth can be harnessed to boost the size of state rainy day funds. The overall goal is to identify the portion of state revenue collections that can be considered “extraordinary” in any given year and then use a significant portion of these funds to stock rainy day funds for use in slow times. Extraordinary revenues are those that are both above the amount that would be collected under average growth rates and also total more than is needed to fully fund the current costs of the existing mix of services the state has decided to provide. Both of these conditions must be met to avoid diverting revenues to restock rainy day funds just after a downturn, for example, when state revenue collection growth rates often exceed average rates but revenues remain well below pre-recession levels.

All states are subject to the ups and downs of the business cycle, but the mix of industries and taxes in a state affects the timing and severity of those swings and their impact on tax collections. The states that face the greatest volatility should also have a higher-than-average ability to fill these reserves as their revenue collections will likely grow more quickly when the economy is expanding.

States can manage a particularly volatile revenue stream, such as capital gains taxes or oil and gas receipts, by dedicating a certain share of revenues from that specific stream toward its rainy day fund. For example, in 2010, Massachusetts began to require that capital gains tax revenue in excess of $1 billion per year be deposited in the rainy day fund. This provides an additional source of funding for the rainy day fund during periods of economic growth.

Spend on One-Time Needs. While increasing the size of state rainy day funds would help smooth the impact of business cycles, there are practical and political limits to the amount of funds that a state can set aside at any one time. This has often led to the use of tax collections generated by “extraordinary” revenue growth for permanent changes such as tax cuts or new spending programs. This, in turn, can lead to future budget gaps. These funds could be used instead for measures that are also one-time in nature, such as building schools or bridges, early retirement of debt, improving pension funding, or shoring up unemployment insurance trust funds. One advantage of using temporary revenues in these ways is that it could reduce the state’s overall indebtedness and increase a state’s capacity for borrowing for capital improvements in bad times. Another is that larger unemployment insurance and pension trust funds provide a better cushion for demands in slow economic times.

Some states have implemented budget management measures along these lines. For example, North Carolina’s budget separates out recurring and non-recurring revenues in its budget. This information could allow policymakers to use non-recurring revenues for purposes that are one-time in nature, although that is not the current practice. Alabama provides a different model. The state’s budget includes a list of spending priorities that are contingent on receipt of revenues that exceed the amount originally budgeted.[11] Either state’s method could be adapted to designate funding that exceeds normal growth rates for one-time expenditures.

Changes to Tax Design

States can reduce volatility while retaining a progressive income tax by relying on a mix of taxes and making temporary changes to the income tax in response to economic volatility.

Rely on a mix of state taxes. Different types of taxes respond differently to the ups and downs of the economy. Relying on a variety of taxes rather than primarily on one type can offset the effects of volatility in one type of tax as changes in the collections of one tax may well offset changes in a different tax.

When the economy declines dramatically, as in the last recession, reliance on a mix of different taxes can delay the impact on state revenue collections. At the onset of the last recession, for example, sales taxes collections were the first to drop. This occurred because merchants generally are required to transfer sales tax collections to states within a few months of when purchases are made. Much of the effect of the recession on income tax collections, on the other hand, was delayed until April of the year after the recession began when the drop in employment and the decline in investment income resulted in large refunds when taxpayers filed their taxes.

Including taxes in the mix that respond to factors other than overall economic growth, such as severance taxes, can add stability despite the fact that they may also be volatile when considered separately. For example, states like New Mexico and North Dakota were not hit as hard by the last recession because high oil prices resulted in increased severance tax collections at a time when collections of other taxes were dropping. The results of a Federal Reserve study of states including several that levy substantial taxes on mineral resources, suggest that severance taxes, while highly volatile, are likely to be counter cyclical.[12] The expanded extraction of natural gas from shale deposits across the United States provides an opportunity for many more states to add severance taxes to the mix of revenues.

Do not restrict local use of property taxes. Local governments can help to offset some of the effects of the volatility of state tax systems. The property tax, a major source of revenue for cities, counties, and school districts, responds more slowly to economic changes than the sales or income tax. A state’s overall support for education, health, transportation, and other services will be more stable if the state does not limit local government’s ability to raise adequate funds by imposing property tax limits.

Raise income tax rates temporarily in recessions; provide rebates in times of high growth. Another way to reduce volatility is to make temporary, rather than permanent, changes in income tax structures in response to short-term declines or spurts of economic growth.

In the past, states often enacted income tax surcharges in bad economic times. These can take the form of a percentage add-on to taxes owed or a temporary rate increase. These surcharges allow a state to maintain programs and provide additional assistance to vulnerable residents during a downturn without permanently raising tax rates.[13]

A surcharge could also be designed to focus on high-income taxpayers who are best able to afford tax increases, leaving the vast majority of taxpayers with no tax increase. In addition, tax increases on individuals and businesses at the top of the income spectrum, who are unlikely to spend less as a result, are preferable to spending cuts in an economic downturn.[14] This is especially true when the cuts in question threaten to undermine the underpinnings of a sound economy — a high-quality education system, access to college, and modern transportation networks, for example.

Rather than damage these fundamental economic building blocks, state policymakers can temporarily raise taxes on high-income households and profitable corporations through the state income tax. While some claim that these kinds of tax increases will harm the state’s economy by driving large numbers of affluent people to other states, this claim is false.[15]

States can also smooth the ups and down of tax collections by providing tax rebates rather than permanent tax cuts when tax collections are growing faster than normal. Permanently cutting tax rates could serve to magnify state revenue problems when a business cycle inevitably turns down. Temporary rebates will not have this effect.

Federal Assistance During Downturns Can Reduce the Impact of Volatility

State tax volatility is not merely a problem for states — it is also a federal problem. When state tax revenues fall in recessions, states typically cut back on programs and services, meaning that they cancel contracts with private vendors and lay off workers. This in turn reduces aggregate demand on the economy, exacerbating the national recession. While states should take the actions described above to reduce volatility, they are unlikely to completely offset it. As a result, the federal government can and should continue to play an important role in softening the effects of volatility. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, enacted in February 2009, included substantial assistance for states, including about $135 billion to $140 billion over a roughly 2.5-year period to help states maintain current activities.

As we look ahead to the inevitability of future swings in the economy, the federal government could expand this role by instituting automatic triggers in programs like Medicaid that would increase aid when the economy declines. States should work with the federal government to design these kinds of triggers.

Conclusion

Progressive income taxes have many advantages as part of state tax systems. These advantages far outweigh the disadvantage of more volatility relative to some other state taxes. Over the long term, a mix of taxes that include a progressive income tax is much more likely to generate revenue that is sufficient to fund the ongoing needs of a state. Income taxes are also fairer than other state taxes. Higher-income families pay a larger share of their income than low- and middle-income families under an income tax.

States can address revenue volatility without eliminating the income tax or making it less progressive. Improvements to budget procedures, such as maintaining a larger rainy day reserve or using extra revenues from good economic times for one-time expenditures, as well as changes to state tax structures can accomplish the goal of offsetting volatility — while retaining the advantages of the income tax.

End Notes

[1] Donald J. Boyd and Robert B. Ward, “How To Address Rising Volatility in State Tax Systems,” The Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government, April 2011.

[2] See, for example, Arthur B. Laffer, Stephen Moore, and Jonathan Williams, 2012, Rich States, Poor States: 5th Anniversary Edition, p. 32; and David Block and Scott Drenkard, “Governor Brown’s Tax Proposal and the Folly of California’s Income Tax,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact, August 1, 2012.

[3] Figure 1 and other figures in this paper use tax collection data from the Census Bureau, which does not factor out changes in tax rates so the changes shown in Figure 2 are the result of tax rate and base changes as well the impact of changes in the economy on tax collections. However, studies that factor out the effect of legislated changes in tax rates and bases also find that sales and income tax collections rise and fall with the economy.

[4] In addition to the personal income tax, many states levy a corporate income tax on business profits. Corporate income taxes make up just a small share of state revenues. Corporate income taxes are more volatile than other state taxes and are also responsive to the business cycle. Throughout this paper, income tax refers to just the personal income tax unless otherwise noted. However, many of the issues noted concerning personal income taxes also apply to state corporate income taxes.

[5] Donald Bruce, William F. Fox, and M.H. Tuttle, “Tax Base Elasticities: A Multi-State Analysis of Long-Run and Short-Run Dynamics,” Southern Economic Journal 73 (2), 2006 and Russell S. Sobel and Randall G. Holcombe, “Measuring the Growth and Variability of Tax Bases Over the Business Cycle,” National Tax Journal, Vol. 49, no. 4, December 1996.

[6] Phil Oliff, Chris Mai, and Vincent Palacios, “States Continue to Feel Recession’s Impact,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 27, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=711.

[7] Higher volatility does not automatically bring higher long-term growth for all state taxes. For example, the corporate income tax is more volatile than the personal income tax but also grows more slowly over the long term. See, for example, R. Alison Felix, “The Growth and Volatility of State Tax Revenue Sources in the Tenth District,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review, Third Quarter 2008.

[8] Howard Chernick, Cordelia Reimers, Jennifer Tennant, “Tax Structure and Revenue Instability: The Great Recession and the States,” preliminary draft, January 3, 2013.

[9] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States,” January 2013.

[10] Iris J. Lav and Alan Berube, “When it Rains it Pours: A Look At The Adequacy of State Rainy Day Funds and Budget Reserves,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 1999.

[11] As currently structured, this rule has been problematic in practice for a number of reasons, including the degree of discretion given to the executive branch to determine whether the funds can be released.

[12] R. Alison Felix, “The Growth and Volatility of State Tax Revenue Sources in the Tenth District,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review, Third Quarter 2008.

[13] Elizabeth McNichol and Andrew Nicholas, “Using Income Taxes to Address State Budget Shortfalls,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 21, 2008.

[14] Nicholas Johnson, “Budget Cuts or Tax Increases at the State Level: Which Is Preferable When the Economy is Weak?” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 28, 2010, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=1032.

[15] For a discussion of this issue see, Robert Tannenwald, Jon Shure and Nicholas Johnson, “Tax Flight Is a Myth: Higher Taxes Bring More Revenue, Not More Migration,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 4, 2011, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3556.