Policymakers in a number of states, including Alabama, Maine, Montana, North Carolina, and Ohio, are promoting deep cuts in personal income taxes as a prescription for economic growth. This approach is not supported by the preponderance of the relevant academic research and has not worked particularly well in the past. The states that tried deep income tax cuts over the last three decades have not seen their economies surge as a result.

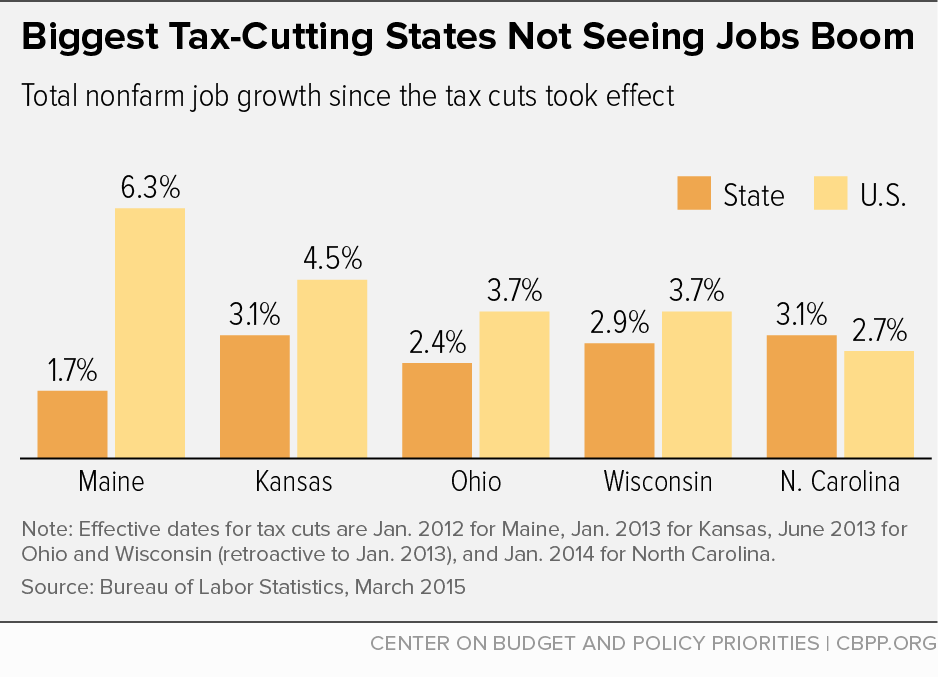

- Four of the five states that enacted the largest personal income tax cuts in the last few years have had slower job growth since enacting their cuts than the nation as a whole.

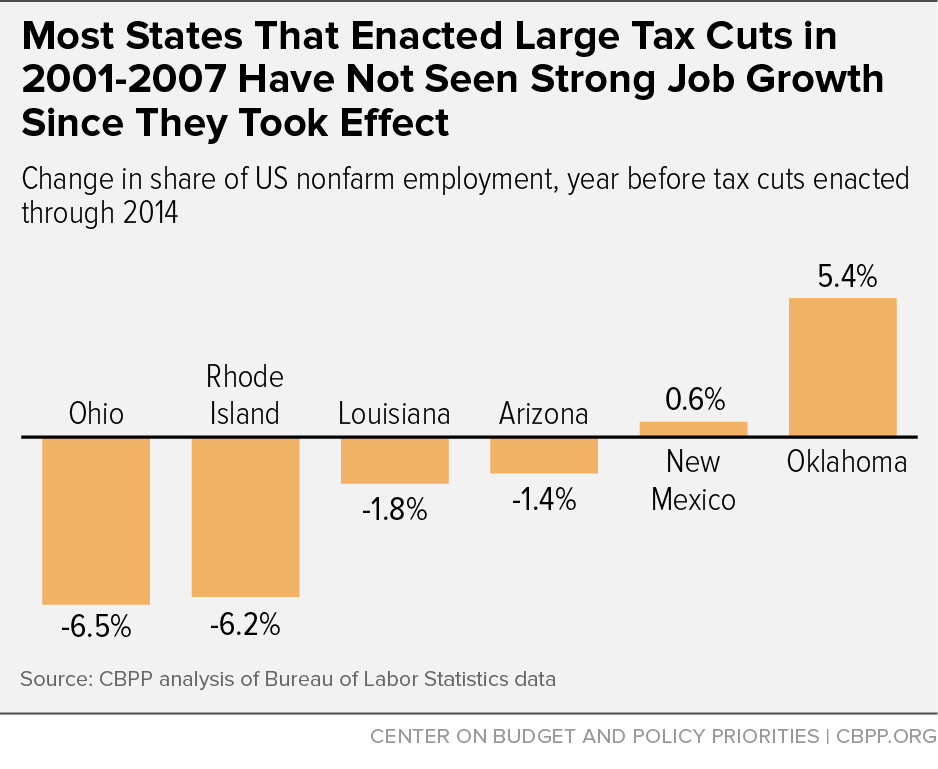

- Four of the six states that cut personal income taxes significantly in the 2000s have seen their share of national employment decline since enacting the cuts. The exceptions ― New Mexico and Oklahoma ― grew mostly because of a sharp run-up in oil prices in the mid-2000s.

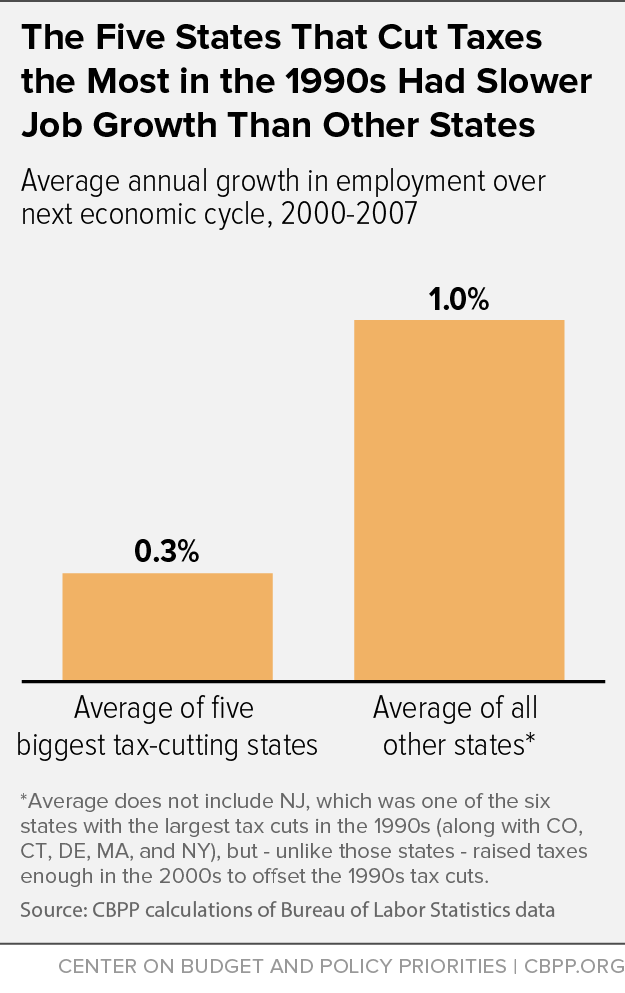

- States with the biggest tax cuts in the 1990s grew jobs during the next economic cycle at an average rate only one-third as large as more cautious states.

These facts illustrate an important finding from a multiplicity of empirical academic studies by economists over the last 40 years. The large majority of these studies find that interstate differences in tax levels, including differences in personal income taxes, have little if any effect on relative rates of state economic growth. Of the 15 major studies published in academic journals since 2000 that examined the broad economic effect of state personal income tax levels, 11 found no significant effects and one of the others produced internally inconsistent results.

Despite the evidence that cutting personal income taxes does little to boost state economies, states may still be tempted to take the risk. That would be a mistake. With revenues in most states still weakened by the recession and reserves only partially recovered, states have little margin for error. Gambling on a personal income tax cut would put fundamental public services, which in most states depend significantly on personal income taxes, at risk. And with the federal government on track to impose further reductions in funding for schools and other services states provide, states have additional reason to protect their own revenue to limit damage to public services.

The idea that cutting personal income taxes might boost the economy is not new. Over the last three decades, a significant number of states have tried this approach. The results make clear that deep personal income tax cuts are no panacea for state economies. States that followed this prescription for growth did not do particularly well in later years.

There are a number of good reasons why both real-world results and the academic literature lend little support for personal income tax cuts as a strategy for boosting state economies. For example:

- It’s a zero-sum game. Because states must balance their budgets, they must pay for tax cuts by cutting state services, raising other taxes, or both. Those actions slow the economy, offsetting the economic benefit of the tax cuts.

- State and local taxes help pay for services that households and businesses want and need. State and local taxes are often higher in some locations than others because they are financing higher-quality public services: better schools, universities, roads, and mass transit; more public recreational facilities; better police protection; etc. When higher taxes pay for better services, they may have no adverse impacts on business decisions on where to locate; they may even have positive impacts (when, for example, the reduction in other business costs exceeds the taxes themselves).

- Other factors are much more important to a state’s economic growth. Trends in the national and international economy, a state’s natural resources, the education of its workforce, the proximity to major markets, and the mix of industries in a state - these are among the major factors that determine the growth of state economies. Interstate differences in state personal income taxes are a very minor issue.

More than a dozen states have cut personal income tax rates in recent years in hopes of spurring their economies in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Five states ― Kansas, Maine, North Carolina, Ohio, and Wisconsin ― enacted especially large cuts in the last five years.[1] In all five states, leading policymakers claimed that the tax cuts would produce stronger economic growth. For example, after signing the cuts in his state, Kansas Governor Sam Brownback claimed, “Our new pro-growth tax policy will be like a shot of adrenaline into the heart of the Kansas economy.”[2]

None of these big tax-cutting states have seen their economies surge since enacting the tax cuts. For instance:

In the 2000s, before the onset of the Great Recession in late 2007, six states — Arizona, Louisiana, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island — enacted significant personal income tax cuts. In every case, proponents claimed the tax cuts would improve the state’s economic standing, just as proponents of similar cuts today claim. For example, the House Majority Leader in Rhode Island said, “This new tax rate . . . is certain to create new jobs, spur economic development, put money back in taxpayers’ pockets, and otherwise bring Rhode Island to a position of twenty-first century economic leadership in the region and, indeed, in the country.”[5]

Since enacting the tax cuts, four of the six states ― Arizona, Louisiana, Ohio, and Rhode Island ― have seen their share of national employment decline, and New Mexico’s share of national employment has risen only slightly. (See Figure 2.) Only Oklahoma has seen its share of national employment rise markedly.

Further, the jobs performance of New Mexico and Oklahoma likely has little to do with the tax cuts. Both states are major oil and natural gas producers whose economies benefited from the tripling of oil prices in the mid-2000s and the rapidly growing use of a new technique for extracting oil and gas that combines horizontal drilling with hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking.” Indeed, these two states have seen their share of national employment drop in the last couple of years as oil prices stagnated and then declined sharply, reversing some ― but not all ― of the price growth from earlier years. More specifically, both New Mexico and Oklahoma have seen their share of national employment fall by 3 percent since October 2012.[6]

States that experimented with large cuts in personal income taxes in the 1990s also did not perform particularly well in later years.

As the economy emerged from the recession of the early 1990s and entered the remarkable boom period of the middle and late 1990s, many states enacted tax cuts. In six states — Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York — the cuts exceeded 10 percent of state revenue.[7] Each of these states enacted major personal income tax cuts.

As they do today, proponents of tax cuts in the 1990s often asserted that tax cuts necessarily strengthen state economies. For example, Connecticut Governor John Rowland claimed that the “key to economic growth is cutting taxes and cutting spending to create jobs. . . . By returning more money back to people’s purses and pockets, we will stimulate the economy, create jobs, and expand our tax base.”[8]

But after enacting the cuts, Connecticut and the other biggest tax-cutting states saw their economies grow more slowly than the economies of more cautious states. Between 2000 and 2007 — the first full economic cycle following implementation of the tax cuts[9] — the states that had cut taxes most:

- Created fewer jobs. The top five tax-cutting states saw job growth of less than 0.3 percent per year, on average, compared with 1.0 percent for the other 44 states. (We exclude New Jersey because it, alone among the biggest tax-cutting states, raised taxes by enough in the 2000s to offset fully the 1990s tax cuts.)

- Had slower income growth. In four of the five biggest tax-cutting states ¾ all but Delaware ¾ personal income grew more slowly than it did on average in the other 44 states. In none of the biggest tax-cutting states did personal income growth exceed inflation.

The lackluster results from states that cut personal income taxes over the last two decades are consistent with the strong consensus from a large number of empirical studies conducted by economists over the last 40 years. The large majority of these studies find that interstate differences in tax levels have little if any effect on relative rates of state economic growth.

This is particularly true of studies of the impact of state personal income tax levels on economic growth. Of the 15 major studies published in academic journals since 2000 that examined the effect of state personal income tax levels on broad measures of state economic growth, 11 found no significant effects and one of the others produced internally inconsistent results (see Table 1).

| Table 1: Most Major Studies Published in Academic Journals Since 2000 Find That State Personal Income Tax Levels Do Not Affect Economic Growth |

|---|

| Citation |

Do Personal Income Tax Levels Affect Economic Growth? |

Key Quotes |

|---|

| Richard V. Adkisson, Mikidadu Mohammed, “Tax Structure and State Economic Growth During the Great Recession,” Social Science Journal, 2014 |

No |

“[I]f one percentage point of [the sales tax’s share of total] revenue collections is transferred [i.e., shifted] to personal income tax, the model predicts a 0.02% increase in both one-year and two-year growth rates. . . . The empirical evidence here suggests that marginal differences in tax structure have detectable but very small impacts on growth rates, at least in the context of the Great Recession. Given this evidence, states facing economic downturns should not rush to adjust their tax structures if their goal is to enhance their growth prospects. At least they should not expect large changes if they do.” [Emphasis added] |

| James Alm and Janet Rogers, “Do State Fiscal Policies Affect State Economic Growth?” Public Finance Review, July 2011 |

No |

“Similar results are found for the individual income tax variable. . . . The estimated coefficient is never [statistically] significantly negative . . . but its coefficient is often significantly positive [i.e., indicates that higher state personal income taxes are associated with higher state economic growth].” |

| Stephen P.A. Brown, Kathy J. Hayes, Lori L. Taylor, “State and Local Policy, Factor Markets, and Regional Growth,” Review of Regional Studies, 2003 |

Yes |

“We construct proxies for effective tax rates by dividing state and local government revenues from sales, property, individual income, and corporate income by gross state product. . . . There is no combination of rising taxes and rising public spending that is positively associated with growth in private capital. . . .” |

| Howard Chernick, “Redistribution at the State and Local Level: Consequences for Economic Growth,” Public Finance Review, 2010 |

No |

“The progressivity of a state’s tax structure does not have a statistically significant effect on the rate of growth of personal income. . . . Income tax burdens do not have a [statistically] significant effect on growth. . . . The most striking policy implication of this study is that tax cuts for high-income taxpayers cannot be justified in terms of growth in state income. Although such cuts may benefit current taxpayers, there is no evidence of a spillover or trickle-down effect to the overall state economy.” |

| Brian Goff, Alex Lebedinsky, Stephen Lile, “A Matched Pairs Analysis of State Growth Differences,” Contemporary Economic Policy, 2011 |

Yes and No |

“Taken as a unit, our results provide strong support for the idea that lower tax burdens tend to lead to higher levels of economic growth. Among tax variables, individual income taxes matter most. . . . In terms of the matching exercise, this restrictive sample comes the closest to producing a comparison of ‘twin’ states, such as Kentucky and Tennessee and New Hampshire and Vermont. Policy analysis based on these states would indicate that higher tax burdens and, in particular, higher individual income-tax rates . . . promote higher growth. . . .” |

| J. William Harden and William H. Hoyt, “Do States Choose Their Mix of Taxes to Minimize Employment Losses?” National Tax Journal, March 2003 |

No |

“We find the corporate income tax has a [statistically] significant negative impact on employment while the sales and individual income taxes do not. . . .” |

| Randall G. Holcombe and Donald J. Lacombe, “The Effect of State Income Taxation on Per Capita Income Growth,” Public Finance Review, May 2004 |

Yes |

“The results show that over the 30-year period from 1960 to 1990, states that raised their income tax rates more than their neighbors had slower income growth and, on average, a 3.4% reduction in per capita income.” |

| Bruce Howard, “Does the Mix of a State’s Tax Portfolio Matter? An Empirical Analysis of United States Tax Portfolios and the Relationship to Levels and Grow in Real Per Capita Gross State Product,” Journal of Applied Business Research, 2011 |

No |

“A weak but statistically significant positive relationship between the index of annual growth in per capita gross state product and the index for individual income tax share was evidenced in the 1993-99 pooled data [i.e. greater reliance on income taxes was associated with stronger economic growth]. . . . It is hard to place too much confidence in this result because when testing on a year-by-year basis, statistical significance at a confidence level of 90% or greater for the tax index coefficient was achieved for only 1 of the 7 years. Furthermore, there was no statistically significant relationship between the index of per capita level of GSP and the individual income tax index. . . . The empirical results suggest that at the state level . . . taxing individual income is more neutral [in its effects on economic growth] than taxing either property or gross receipts.” |

| Andrew Leigh, “Do Redistributive State Taxes Reduce Inequality?” National Tax Journal, March 2008 |

No |

“Regarding the efficiency cost of taxation, I find no evidence that states with more redistributive taxes experience slower growth in per capita personal income. (If anything, states with redistributive taxes grow faster.)”

|

| Andrew Ojede and Steve Yamarik, “Tax Policy and State Economic Growth: The Long-Run and Short-Run of It,” Economics Letters, 2012 |

No |

“This paper used a pooled mean estimator to estimate the short-run and long-run impacts of state and local tax policy on state-level economic growth. . . . The results found that property taxes lowered both short-run and long-run economic growth, sales taxes lowered long-run growth, while income taxes had no short-run or long-run impact.” [Emphasis added.] |

| Barry W. Poulson and Jules Gordon Kaplan, “State Income Taxes and Economic Growth,” Cato Journal, Winter 2008 |

Yes |

“The analysis underscores the negative impact of income taxes on economic growth in the states. . . . Jurisdictions that imposed an income tax to generate a given level of revenue experienced lower rates of economic growth relative to jurisdictions that relied on alternative taxes to generate the same revenue.” |

| W. Robert Reed, “The Determinants of U.S. State Economic Growth: A Less Extreme Bounds Analysis,” Economic Inquiry, October 2009 |

No |

Note: No direct quotes in the paper summarize findings with respect to the effects of personal income taxes on state economic growth. However, average effective personal income tax rates were not identified in Table 3 of the paper as a statistically “robust” variable in explaining state economic growth in an analysis using the level of and 5-year growth in the explanatory variables. Footnote 25 indicates that higher personal income taxes were actually associated with higher economic growth in the 10-year analysis. |

| W. Robert Reed and Cynthia L. Rogers, “Tax Cuts and Employment Growth in New Jersey: Lessons from a Regional Analysis,” Public Finance Review, May 2004 |

No |

“This study’s analysis does not support the hypothesis that [personal income] tax cuts stimulated employment growth in New Jersey.” |

| Dan S. Rickman, “Should Oklahoma Be More Like Texas? A Taxing Decision,” Review of Regional Studies, 2013 |

No |

“[T]here is not compelling evidence that Texas economically out-performs Oklahoma. . . . Controlling for other differences between Oklahoma and Texas using county level data for all neighboring states revealed few growth advantages, in which the only advantage post-2000 occurred during 2007 to 2010. Notably, Texas did not enjoy any advantages during the 2000 to 2007 period, which is prior to when Oklahoma continued to reduce its personal income tax rate. . . . The evidence above suggests that eliminating the [Oklahoma] state income tax at best would have no impact. At worst, if Oklahoma’s adjustment to elimination of the state income tax in terms of spending and alternative taxes is worse than that of Texas, the Oklahoma economy could be harmed. Vital investments in education and infrastructure could be harmed, which could more than offset any gains from reducing income taxes.” |

| Marc Tomljanovich, “The Role of State Fiscal Policy in State Economic Growth,” Contemporary Economic Policy, July 2004 |

No |

“The coefficients on [personal] income tax rate and property tax rate are statistically insignificant. . . . Subdividing state revenues and expenditures into individual components therefore reinforces the lack of impact of individual [income] tax rates on long-run state economic growth. . . .” |

Studies focusing on narrower issues, such as the impact of personal income tax levels on interstate migration and entrepreneurship, also have found little or no impact. For instance, a carefully designed study by two Princeton University researchers on the impact of personal income tax increases on interstate migration concluded that a tax increase on high-income earners in New Jersey “raises nearly $1 billion per year, and tangibly reduces income inequality, with little cost in terms of tax flight.”[10] And a rigorous 2012 study commissioned by the U.S. Small Business Administration found “no evidence of an economically significant effect of state tax portfolios on entrepreneurial activity.”[11]

Despite the lack of academic evidence supporting income tax cuts as an economic growth strategy, policymakers may be tempted to take the risk. This would be a mistake. The potential downsides of an ill-advised income tax cut for families, communities, and the state outweigh the advantages for a number of reasons, including:

- States have little margin for error. States have yet to fully recover from the severe 2007-09 recession, which caused budget shortfalls totaling well over half a trillion dollars.[12] Revenues have only barely returned to where they were seven years ago — far below what is required, since the number of people needing state services has grown. There are, for example, about 485,000 more students enrolled in preK-12 schools than before the recession, but about 289,000 fewer teachers and other school employees.[13] Further, states largely drained their “rainy day funds” and budget reserves during the recession and have yet to fully replenish them in many cases. Enacting tax cuts now, when state finances remain fragile, would make it even harder for states to recover fully from the recession and prepare for the next one.

- Fundamental state services depend on income tax revenue. In most states, schools, universities, health care services, public safety, and other public services rely heavily on funding from the personal income tax. Because states must balance their budgets, personal income tax cuts that fail to produce the promised economic gains almost certainly will lead to deep funding cuts for schools and other public services.

- The federal government is on track to cut funding for states. The 2011 Budget Control Act already has caused cuts in grant programs to states and will push federal funding for a wide range of state and local services — schools, water treatment, law enforcement, and other areas — to its lowest level in four decades as a share of the economy.[14] Additional cuts known as “sequestration” will further reduce funding for states over the next several years, unless policymakers agree on a plan to avoid them. States need to prepare to limit the damage from these federal funding cuts, not exacerbate the problem by cutting their own revenue.

States considering personal income tax cuts this legislative session should be skeptical of claims that these tax cuts will improve the state’s economic performance. In the last two decades, a number of states have cut taxes deeply in hopes of spurring economic gains, with unimpressive results. That’s not surprising given that the preponderance of the peer-reviewed academic studies indicate that state and local personal income tax levels do not affect economic performance.

Rather than bet their futures on a tax-cutting approach that has not worked well in the past, states would do better to concern themselves with improving their schools, transportation networks, and other public services that act as building blocks of economic growth.