Over 100 million people — about a third of the country’s population — are non-elderly adults who don’t have minor children in the family[1] and don’t have severe disabilities. More than 1 in 8 of these adults are in poverty.[2]

Our system of economic and health supports — such as Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and refundable tax credits — is geared largely toward helping children and their parents, people with disabilities, and the elderly. The nation’s basic supports for low-income, non-elderly adults without children, particularly for those who do not meet a rigorous disability standard, are weak, fragmented, and often highly restrictive, leaving many of these individuals without help they need to afford the basics. These adults need stronger supports to help meet essential needs, a problem that the hardships inflicted by the COVID-19 pandemic have magnified.

Compared to the larger population of non-elderly adults, low-income non-elderly adults are more likely to be young, have lower educational attainment, or have a disability that may not be severe enough to qualify for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) but nonetheless prevents or limits work. Due to systemic racism and other factors that have resulted in fewer educational and employment opportunities, non-elderly adults who identify as Black or Latino are more likely to have low incomes.

Most of these adults who are able to work do so, but they often hold jobs with greater turnover and volatility that don’t pay high enough wages to enable these adults to meet basic needs such as adequate, nutritious food and safe, stable housing. Often these jobs also do not provide benefits like employer-based health insurance.

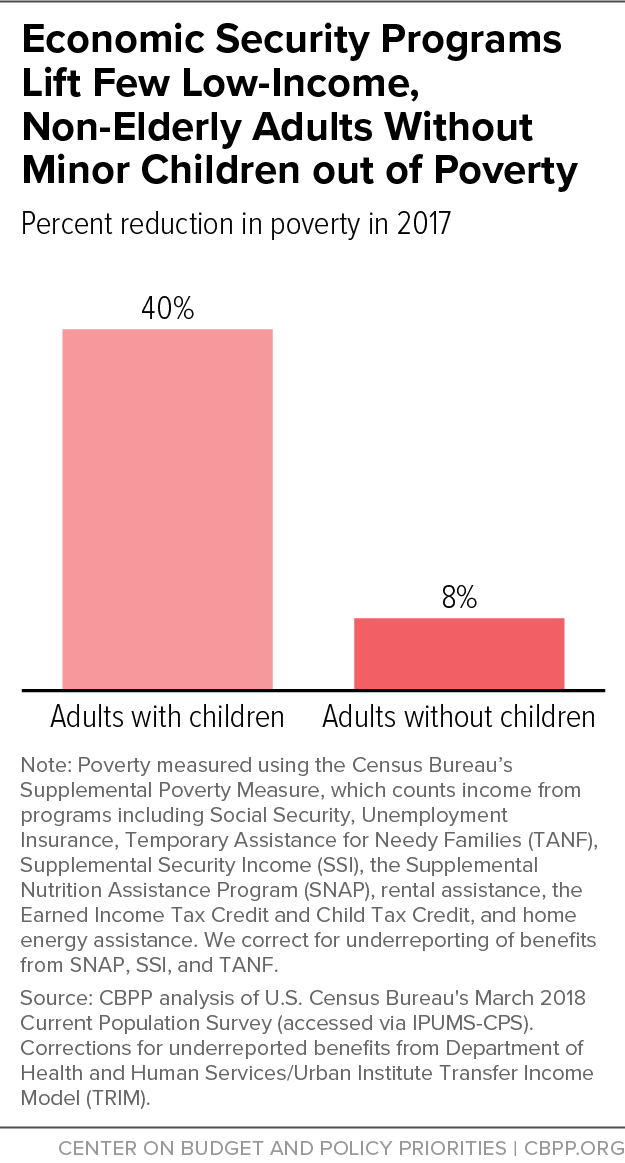

The nation’s system of economic and health supports often leaves these adults unassisted or aided to only a small degree. While the current system of economic security programs reduces the number of non-elderly adults with minor children in poverty by 40 percent by lifting their family incomes above the poverty line, these programs reduce poverty by only 8 percent for non-elderly adults without minor children. (See Figure 1.)

- Low-income, non-elderly adults not living with a minor child are more likely to lack health insurance (29 percent) than those living with children (24 percent).[3] This problem is most severe in the 14 states that haven’t implemented the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion, where these adults are ineligible for health insurance through Medicaid (unless they have a serious disability).

- One in ten households without minor children experienced food insecurity in 2019. For the subset of this group that consists of low-income, non-elderly adults who aren’t living with minor children and don’t have a disability, food assistance is available through SNAP for only three months out of every 36 while they aren’t employed or participating in a work or training program at least half time, unless they live in an area temporarily exempt from this restriction because of elevated unemployment.

- Some 9.3 million non-elderly adults not living with minor children both meet the eligibility criteria for federal rental assistance and pay more than half of their income for rent, but only 1.9 million of them — 1 in 5 — receive any such assistance. Housing assistance is very constrained due to funding limitations, resulting in large unmet need.

- Workers without minor children are the only demographic group that contains people whom the federal tax system taxes into, or deeper into, poverty. That’s in part because they are eligible only for a tiny Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) that is too small to offset the federal taxes (primarily payroll taxes) they owe, or are eligible for no EITC at all.

- Only about half of the states have General Assistance programs that provide basic cash aid to very poor people without minor children in the home, and fewer than half of those states provide any such benefits to people who don’t have a disability or other specified barrier to employment.

Many non-elderly adults without children have disabilities or illnesses that make working difficult. Most federal programs that provide benefits to individuals with disabilities, however — such as SSI and SSDI — generally provide benefits only to individuals with severe and long-lasting impairments. Many people with work-limiting impairments are ineligible for disability benefits despite being out of work or able to work only modest amounts.

The federal government has left it up to states to decide whether to provide any cash assistance to low-income, non-elderly adults without children who don’t meet the disability standard for SSI and SSDI. If states do provide such help, it’s entirely up to them to decide how much to provide and under what conditions. Most states have never provided substantial support for this group. Moreover, income support for these individuals has weakened substantially over the past 30 years and continues to erode.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the economic hardship it has caused have further exposed critical gaps in America’s system of economic and health supports. Low-income, non-elderly adults without children have been particularly hard hit, due to their low incomes and disproportionate employment in low-paid industries that have experienced larger job losses. In addition, Black, Latino, and Indigenous people as well as immigrants have been affected disproportionately by both the health crisis and its economic fallout.[4] With millions of people unemployed or facing substantial income losses during the COVID-19 economic downturn, the lack of stronger economic and health supports for this group is having a particularly acute impact.

In 2017, there were over 100 million 18- to 64-year-old adults in the United States without children in the family who didn’t receive Social Security or SSI.[5] One in five had income below 200 percent of the official poverty line (about $25,500 annually for a single individual in 2017); 1 in 10 lived below 100 percent of the official poverty line (about $12,800 annually for a single individual in 2017).[6]

Using the Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), 13.1 percent of non-elderly adults without children lived in poverty in 2017 after accounting for government benefits and certain expenses (such as out-of-pocket medical expenses).[7] This group is more likely to experience poverty than are non-elderly adults with children, whose poverty rate under the SPM was 10.9 percent in 2017.[8] The SPM poverty rate among children, themselves, was 13.6 percent.

The slightly higher poverty rate for children than for non-elderly adults without children in part reflects the smaller family sizes for the latter group. The income level that puts families of one or two members above the SPM poverty line is low ($13,400 for a single individual) compared to the corresponding level for a larger family with children (the SPM poverty line for a family of four is $28,900).[9] Supports for low-income, non-elderly adults without minor children are much less effective at lifting those adults above the poverty line than are the supports available to families with children.

The population of low-income, non-elderly adults without children or disabilities is a dynamic one: employment status and economic status for any individual may change over time. In addition, disability may be short term or longer lasting and may vary in severity over time. And whether the adult has a child in their home may change as they or a child joins or moves out of a home.

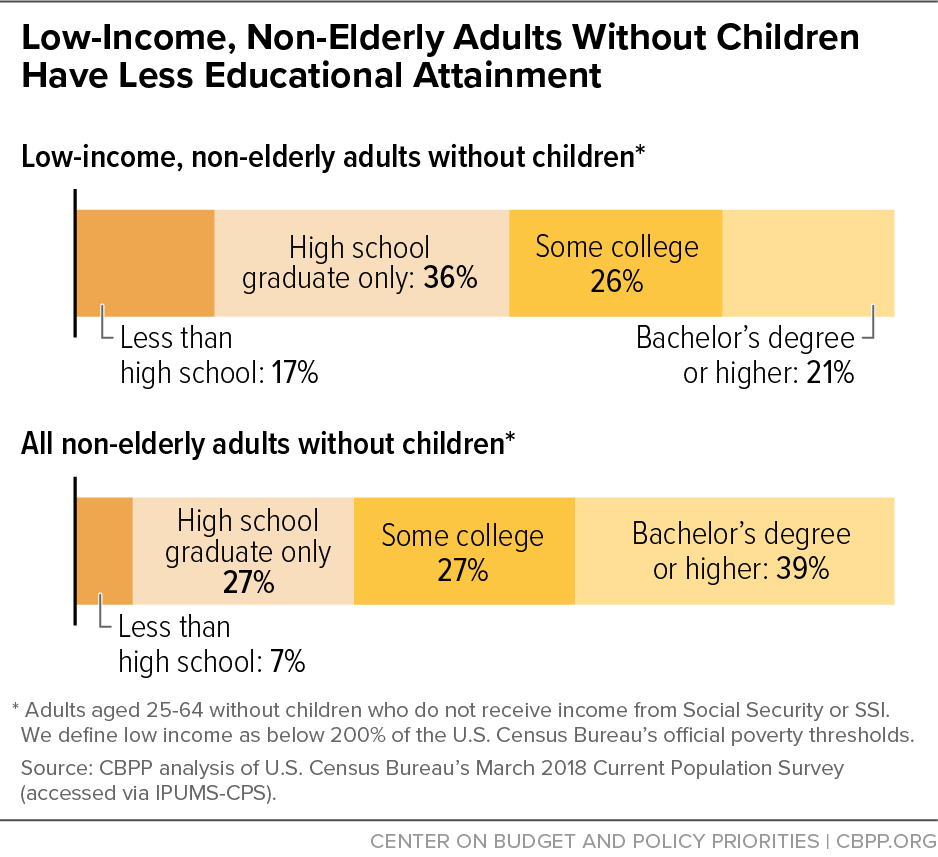

Low-income adults without children generally tend to be younger than all non-elderly adults without children: about 60 percent are under age 45, compared to 52 percent for all non-elderly adults. While the majority of non-elderly adults without children are white, Black and Latino people are overrepresented among those with low incomes, indicative of historical racism and other factors that have led to wide disparities and unequal treatment in housing, education, and employment. And while over one-third of all non-elderly adults without children have a college degree, low-income non-elderly adults without children are only about half as likely to have a college degree, which often limits their employment and economic opportunities. (See Figure 2.) Low-income non-elderly adults without children are also twice as likely as all non-elderly adults to have a disability that limits or prevents work.[10]

Eligibility for some programs is limited to people who are unable to work, and some programs’ definitions of disability do not account for certain physical, mental, or other health conditions that limit the kind or amount of work an individual can do. In some programs, eligibility for non-elderly people who aren’t employed is limited to people receiving SSI or SSDI. But SSI[11] and SSDI[12] have arduous (and lengthy) disability determination processes, and many people with disabilities don’t receive those benefits. Of the more than 46 million adults reporting a disability in 2014, only about 40 percent received cash assistance such as SSI or SSDI.[13] Many did not qualify because their disability did not meet the strict criteria for these programs, which can relate to both the severity and the duration of an individual’s condition.

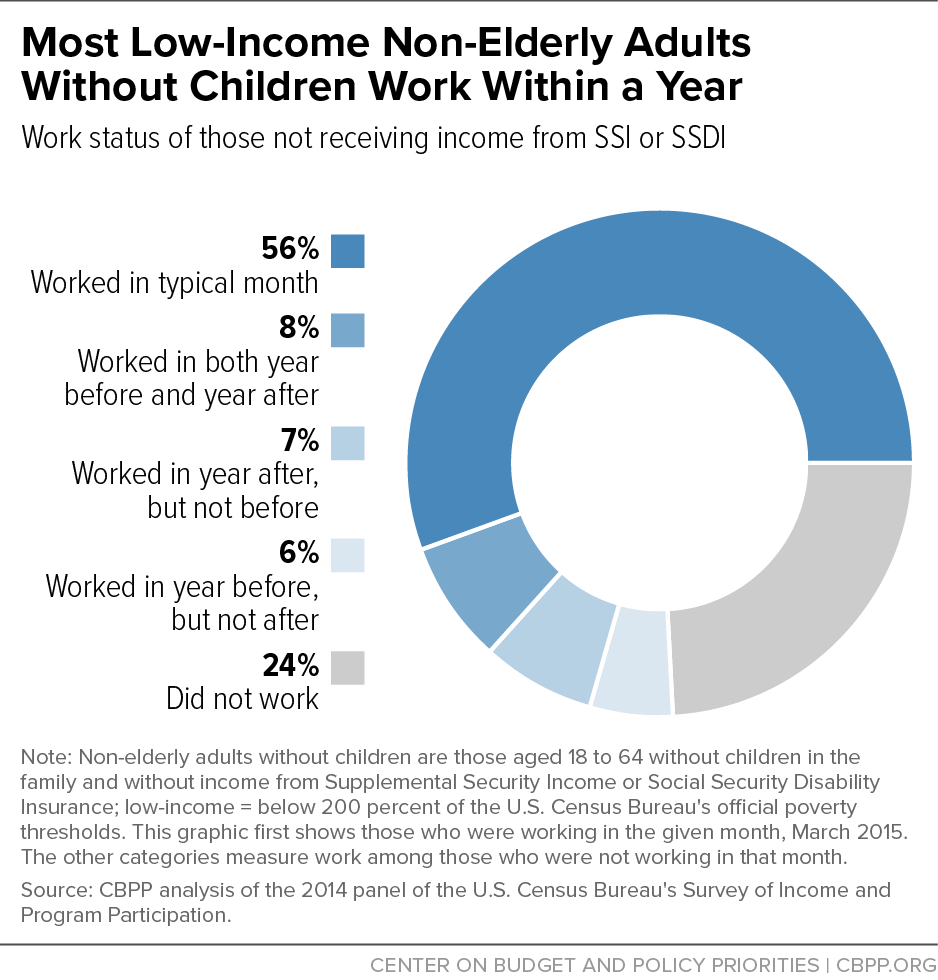

If an adult is deemed able to work, they often are expected to work in order to qualify for benefits. In actuality, work status for this group fluctuates; many people work significant periods of time but also experience periods of joblessness. Work status for this group is better considered over time than at a single point in time.

Most low-income, non-elderly adults who can work do so. Using the most recent longitudinal data from the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP),[14] we examined the employment data pertaining to low-income, non-elderly adults who don’t have children in the family and don’t receive SSI or SSDI. (See Figure 3.)

An adult may be out of work for a period of time for a variety of reasons, including health reasons, school attendance, or the need to care for a family member. Others cannot find work or have been laid off. People who are not working within a year are more likely to identify as having a disability than those who are working. If benefits are contingent on employment, non-elderly adults without children may find themselves ineligible for important assistance, including at times when they need it most.

Educational attainment often plays a role in the availability of employment opportunities. For example, the SIPP data show that people who weren’t employed 12 months before or after the given month we examined tended to have less education than people who worked within that period. An adult’s educational attainment is the result of many factors, including their family’s income when they were children and the quality of the schools they attended. Due to racism and discrimination, people of color disproportionately face barriers to educational and employment opportunities. This is reflected in the SIPP data, which show that people of color were somewhat less likely than those identifying as white to work 12 months before or after a given month, though most people of every racial or ethnic group work.

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic and recession have exacerbated systemic barriers to economic mobility that people of color face. Due to factors including the lack of adequate educational and employment opportunities, Black and Latino workers were more likely prior to the pandemic to be employed in low-paid industries that have seen disproportionately large job losses during the pandemic.[15] Low-paid industries accounted for more than half of the jobs lost from February to December 2020, our analysis found.[16] Similarly, people with a college degree have seen jobs return far more quickly than people without a college degree, exacerbating racial disparities in unemployment.

Economic and Health Programs Often out of Reach for Low-Income Adults Without Children

When these adults do receive assistance, health and economic security programs can increase their access to health insurance, their food security, and their housing stability, ultimately improving their health outcomes and economic well-being. For example, SNAP keeps millions of people out of poverty, reduces food insecurity, and has been linked to positive health outcomes among adults, such as fewer physician visits, fewer days missed due to illness, more positive self-assessments of health status, and a reduced likelihood of demonstrating psychological distress.[17] In addition, the coverage provided by the ACA’s Medicaid expansion yields significant benefits for those who gain coverage, including improved access to health care, better financial security and economic mobility, and better health outcomes such as lower morbidity and mortality.[18] Rental assistance is highly effective at reducing homelessness and housing instability among those receiving it, and by lowering rental costs, it allows low-income people to spend more on other basic needs like food and clothing.[19] The EITC and General Assistance raise low incomes and reduce poverty.

These programs reach far fewer adults without children than the number who need such assistance; many non-elderly adults without children receive little or no assistance despite experiencing serious hardship. Cash aid provided through General Assistance was never substantial and continues to erode, and uneven coverage and restrictive policies limit the ability of various federal economic and health supports to adequately address needs like food, housing, and health care. Although economic security programs reduce the number of non-elderly adults with minor children in poverty by 40 percent, these programs reduce poverty by only 8 percent for non-elderly adults without minor children.[20] Strengthening these supports for non-elderly adults without children would be particularly important to improving the well-being of people of color and immigrants, who typically have fewer assets to fall back on during hard times.

In addition, many immigrants with very low incomes are ineligible for various forms of public assistance due to their immigration status, including people with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals or Temporary Protected status, people with temporary visas related to a variety of factors like schooling, people filling jobs needed in certain economic sectors, and lawful permanent residents who are in their first five years of having that status. These restrictions in accessing support place many immigrants and members of their families in an especially vulnerable situation amid the COVID-19’s pandemic and economic crisis. In other cases, lawfully present immigrants or members of their families are eligible for help from programs like SNAP or Medicaid but often forgo that assistance out of fear of the Trump Administration’s harsh “public charge” policies, which can place immigrants at risk if they receive those benefits despite being eligible for them.[21] If immigrants and their family members are afraid to access help for which they qualify, they are more likely to face serious hardships like eviction, poor health outcomes, homelessness, and hunger.

The economic and health programs discussed in this paper cover non-elderly adults without children to varying degrees, but the programs’ eligibility restrictions with respect to this population leave many adults in need with little or no assistance. Furthermore, the differences in eligibility across programs can be complex and cumbersome for people to understand and navigate. (See Table 1.) And wide variations across states mean that two otherwise-similar people living in different states may have varying types and levels of assistance available to them.

Medicaid. States have the option to expand Medicaid coverage to low-income adults with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty level, or $17,608 for a single person in 2020. If a state does not adopt the expansion, then among adults who aren’t elderly, disabled, or in need of long-term care, only parents (often only parents with exceedingly low incomes) can qualify for Medicaid. Other non-elderly, non-disabled adults are generally ineligible for Medicaid in these states regardless of how low their incomes are or whether they have access to other coverage.

Thirty-six states and Washington, D.C. have implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion, with two more states planning to implement it in the near future as a result of successful ballot initiatives in 2020. More than 15 million adults had health insurance coverage in 2019 through the Medicaid expansion. But an estimated 6.5 million more would have been covered had all states adopted the expansion. (The figures cited here include both adults with children and adults not raising children in their home.)

SNAP. SNAP provides food assistance to nearly 5 million low-income working-age adults not living with minor children. Nearly 3 million of these individuals, those aged 18 to 49, face much tougher eligibility rules than other participants. In general, they can only receive SNAP benefits for three months out of every 36 months unless they are working or participating in a qualifying work program for at least 20 hours per week, regardless of the availability of work or training programs in their area. People who search diligently for work but can’t find it are cut off the program after three months despite their search efforts. States can waive the three-month time limit for this group for areas within the state that meet certain unemployment thresholds. In 2019, 34 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands had a waiver from this time limit in place in parts of the state with high unemployment. The time limit has been temporarily suspended nationally during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Federal rental assistance. Rental assistance makes housing affordable by allowing low-income families to pay 30 percent of their income for housing, with a federal subsidy covering the rest. Rental assistance helps about 10 million renters keep a roof over their heads. It also helps people with disabilities; nearly half of the non-elderly (aged 18 to 61) adults without children receiving rental assistance have a disability.[22] Insufficient funding prevents most people in need from receiving any help with the rent, however. Fewer than 1 in 5 eligible non-elderly adults without children receive any rental assistance.

EITC. The Earned Income Tax Credit is a federal tax credit for low- and moderate-income households that increases in value as a person’s earnings rise (up to certain income thresholds); only households with earnings in that year qualify. The credit amount depends on whether tax filers have qualifying children (and if so, on the number of children). For people in certain income ranges, the credit amount also depends on marital status. (This part of the EITC structure is designed to address marriage-penalty issues.) The EITC boosts incomes and reduces poverty, but is far stronger for low-income families with children than for low-income working adults without children, who are eligible only for a small credit or none at all. Largely as a result of the EITC for these workers being so small, the federal tax code taxes about 5.8 million adults between the ages of 19 and 65 who aren’t raising children in their home into, or deeper into, poverty; the federal payroll (and in some cases, income) taxes these workers owe are larger than any EITC they receive. In addition to the federal EITC, some 29 states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico have enacted their own versions of the EITC, which typically are set at a modest percentage of the federal EITC.

General Assistance (GA). General cash assistance is entirely funded with state or local dollars. States can choose whether to have a program at all, and if so, they set their own eligibility criteria and benefit levels. Half the states do not provide any type of GA. Of the 25 states that do, only 11 provide any GA benefits to individuals who are deemed “employable,” meaning that they don’t have a disability or certain other barriers to work. State GA programs served fewer than a half million poor households in December 2019. Benefit levels are very low: maximum benefits fall below half the federal poverty level in most states with GA programs, and below a quarter of the federal poverty level in half of these states.

We do not include Unemployment Insurance (UI) as one of the programs discussed in this report because it is a social insurance program for unemployed workers (regardless of the household’s overall income level) and not a benefit based on financial need. However, UI provides a cash benefit that many unemployed workers rely on to help meet basic needs and is an important economic security program — though one with significant gaps.

UI provides a temporary, partial wage-replacement benefit for workers who lose their job for certain specified reasons. These reasons vary across states but always include workers who lose their job because an employer goes out of business or reduces staffing based on the employer’s need for workers. It is not generally available to those who quit their job, are new entrants into the labor force, or do not meet their state’s requirements for recent work history. Even with the additional weeks of benefits that the federal government usually provides in a period of high and prolonged unemployment, such as during the current economic downturn or the Great Recession, many workers exhaust all available benefits before finding a job.

In non-recessionary times, UI does not reach most unemployed workers. It served fewer than 3 in 10 unemployed workers in an average month of 2018.a In such periods, some unemployed workers exhaust their benefits before finding a new job and many others do not get UI at all, due to outdated eligibility requirements that in some states exclude people such as unemployed workers looking for part-time work and those who leave work for compelling family reasons, like caring for an ill family member. In addition, many unemployed workers do not have sufficient recent earnings or hours of work to meet restrictive state requirements or are not covered at all. This last group includes people working in the gig economy — for example, rideshare drivers or those working through food delivery services — who generally cannot receive UI because they are classified as independent contractors and such workers aren’t in the UI system.

Even for many of those who do receive UI benefits, the benefit level is low, generally replacing half or less of lost wages. States set many of the eligibility rules for UI and also set benefit-level formulas; both the share of jobless workers who qualify and benefit levels vary substantially across states. For example, the share of unemployed workers receiving UI prior to the pandemic ranged from a high of 57 percent in Massachusetts to a low of 9 percent in Mississippi.b In April 2020, average weekly benefits (not counting federal supplemental unemployment benefits then in effect for a temporary period) were about $333 nationwide but ranged from a low of $101 in Oklahoma to $531 in Massachusetts.c

The CARES Act of March 2020 created temporary additional programs or benefits that expanded UI eligibility and the duration and amount of UI benefits. For example, the CARES Act created a Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program, available through the end of 2020 to unemployed workers normally excluded from UI, such as those who had to stop working to care for COVID-stricken relatives, those who didn’t have a long enough work history when they lost their jobs during this crisis, and those working in the gig economy. CARES also increased UI benefit levels substantially through July 2020 and added additional weeks of benefits through the end of 2020. The Emergency Coronavirus Relief bill enacted in in December extended the CARES Act provisions, including an increase in weekly benefits, into March 2021. These CARES Act provisions have temporarily made UI broader and more adequate.

a “Application and Recipiency,” (chart), U.S. Department of Labor, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/images/carousel/application_and_recipiency.png.

b Michael Leachman and Jennifer Sullivan, “Some States Much Better Prepared Than Others for Recession,” CBPP, March 20, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/some-states-much-better-prepared-than-others-for-recession

c CBPP, “Policy Basics: Unemployment Insurance,” updated January 4, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/policy-basics-unemployment-insurance.

The system of economic and health supports for low-income, non-elderly adults without children should be strengthened to close gaps in the current spotty system of assistance. These programs have the potential to substantially reduce financial, housing, and food hardship that many low-income, non-elderly adults without children face. This is especially urgent in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and economic downturn and the increased hardship that low-income households confront. To ensure households have the assistance they need when they fall on hard times, policymakers should:

Expand program coverage and strengthen program benefits. Due to some programs’ limited coverage and benefits, many low-income non-elderly adults are receiving little or no assistance. Expanding program coverage and boosting benefits would provide greater assistance to this group and lift more people out of poverty. For example, all states should adopt the ACA’s Medicaid expansion for low-income adults (and federal policymakers should consider new financial incentives to encourage the remaining states to do so), and the federal government should modify the ACA marketplace coverage that’s offered to low-income adults to better ensure quality affordable coverage in states that continue to decline to expand Medicaid.

Make assistance available to those who don’t have jobs. As described above, some programs make benefits available only to non-elderly adults who are employed or meet a strict definition of disability. This lack of assistance leaves many in need without help and overlooks key nuances about this population. Ultimately, more significant income assistance and fewer eligibility restrictions are needed to reduce poverty and hardship among this group.

Reduce significant variation across states in program rules. Reducing the variation in access to programs and benefit amounts would allow low-income adults to receive more equal support, regardless of residence.

Prevent further restrictions in eligibility and benefits. Some federal and state policymakers have proposed measures that would further restrict eligibility and benefits for key needs-based programs, lessening their ability to provide assistance and meet the needs of low-income adults. Given that economic and health programs can improve health, educational, and employment outcomes, while also alleviating hardship, policymakers should reject efforts to curb access to these benefits.

This report’s chapters describe eligibility criteria, participation data, and measures of effectiveness for low-income, non-elderly adults without children across five types of health and economic security programs: Medicaid, SNAP, HUD rental assistance programs, the EITC, and state General Assistance programs. The table below briefly explains how each program defines and determines eligibility, the benefits available to participants, and variation among states in administering these programs.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| Economic and Health Supports Are Fragmented, Weak for Low-Income, Non-Elderly Adults Without Minor Children in the Family |

|---|

| Program |

Eligibility Affecting Non-Elderly (18- to 64-year-old) Adults Without Minor Children in the Family |

Benefits |

State Variation |

|---|

| Medicaid |

States have the option under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion to cover adults aged 19-64 with incomes at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty level — including adults who don’t have children living in the home and don’t otherwise qualify for Medicaid (i.e., they don’t have a federally recognized disability). |

Access to comprehensive health care that improves health outcomes, financial security, and economic mobility. |

Access to Medicaid for this group largely depends on whether a state has adopted the Medicaid expansion. Currently, 36 states and D.C. have implemented the Medicaid expansion, with future implementation anticipated in two more states as a result of the approval of ballot initiatives. |

| Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) |

Otherwise-eligible adults aged 18-49 (who generally must have gross income below 130 percent of the federal poverty level) who aren’t physically or mentally unable to work, pregnant, or in a household with a minor child can receive SNAP benefits for only three months (out of every 36 months) in which they are not employed or participating in a qualifying work or training program for at least 20 hours per week. Searching for work but being unable to find work does not count as a qualifying work activity. |

Nutritional support to purchase food at designated SNAP retailers. In 2018, the average monthly benefit for one-person households consisting of adults aged 18-49 without minor children was $172. |

The three-month time limit can be lifted in some areas if the state receives a temporary waiver from the time limit, based on elevated unemployment in those areas. In 2019, 34 states, D.C., Guam, and the Virgin Islands had a waiver from the time limit in place, in most cases for part of the state. |

| Federal Rental Assistance |

Adults aged 18-61 without minor children and with incomes at or below 80 percent of the local median income are eligible for housing assistance, but funding is limited. Due to insufficient funding, 7 million eligible households consisting of non-elderly adults without children that pay over half their income for rent are unable to receive any rental assistance. Available resources are targeted to individuals with disabilities; nearly half of non-elderly adults receiving rental assistance have a disability. |

Rental assistance makes housing affordable by allowing families to pay 30 percent of their income for housing, with a federal subsidy covering the rest. |

There are variations in how the program is administered by state and local housing agencies and in how those agencies use the program funding they receive. For example, state and local housing agencies administering Housing Choice Vouchers may choose to prioritize people with disabilities when taking renters from a waiting list for assisted housing. |

| Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) |

Adults aged 25-64 who aren’t raising children in the home and who have earned income below a certain threshold (in 2020, $15,820 for someone who isn’t married, $21,710 for married couples). |

The EITC is a federal tax credit for low-income workers that raises their incomes and reduces poverty. There is a small EITC specifically for workers without children. It provided an average credit of $302 in 2018. Even with the credit, many in this group still owe net federal taxes, despite being below the poverty line. |

States can create their own version of the federal EITC to help low-income working people meet basic needs. Currently, 29 states, D.C., and Puerto Rico have enacted a state EITC, with varying inclusivity and credit amounts. |

| State General Assistance (GA) |

Very low-income adults who are not elderly, do not have minor children in the home, and do not qualify for SSI (or are waiting for an SSI benefit determination) sometimes qualify for GA, depending on whether their state offers a GA program and, if so, its eligibility criteria. Available benefits may differ depending on whether an adult has some disability or barrier to employment. |

Basic cash assistance to supplement income and provide for basic needs. Benefit levels have eroded over the years, and eligibility has become much more restrictive in many states. Currently, benefits are below half the federal poverty level in most states with GA programs and below a quarter of the federal poverty level in half of these states. |

States determine whether or not to provide GA and which groups of individuals to serve. Currently, only 25 states have GA programs at all, and only 11 states provide benefits to individuals who do not have some disability or barrier to employment. Benefit levels vary from state to state. |