- Home

- Poverty And Inequality

- American Rescue Plan: Shots In Arms And ...

American Rescue Plan: Shots in Arms and Money in Pockets

Testimony of Sharon Parrott, President, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Before the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs

Chairman Brown, Ranking Member Toomey, members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify before you this morning at this important hearing. I am Sharon Parrott, President of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research and policy institute in Washington, D. C.

In the following pages, I will make four main points:

- First, the economy still has a large net loss of jobs, millions are out of work, and millions are struggling to put food on the table and have fallen behind on their rent because of the pandemic and its economic fallout. The crisis has taken a disproportionate toll on low-income workers, their families, and people of color, shining a light on and exacerbating the nation’s long-standing racial and economic inequities.

- Second, the American Rescue Plan Act, which builds on the CARES Act and Families First Act of last spring and the December relief package, is providing much needed help for tens of millions of people facing difficulties paying their bills, while also providing important aid to states, localities, territories, and tribes that they can use to fill revenue holes, address COVID-related needs, and address “unfinished learning” that students need to master.

- Third, the nation would have needed fewer stopgap measures during this crisis if we had permanent policies in place that provided sufficient supports for households that struggle to afford the basics, that offered adequate jobless benefits particularly to workers in low-paid jobs who often receive no jobless benefits at all, and that ensured that everyone had health coverage.

The President and Congress will soon have a historic opportunity, through forthcoming recovery legislation, to invest in an equitable recovery that enables everyone to share in its benefits.

- And fourth, the President and Congress will soon have a historic opportunity, through forthcoming recovery legislation, to invest in an equitable recovery that enables everyone to share in its benefits. The nation can afford to make these investments and should start down the road of building a more adequate and fair tax system.

Millions Still Facing Hardship

Over the last year, the global pandemic and resulting economic fallout have taken an enormous toll on the economy and households, imposing steep job losses and great hardship that have fallen disproportionately on people in low-wage jobs and households with children, with particularly steep costs imposed on Black, Latino, immigrant, and Indigenous people.

Lost Jobs and Lost Pay

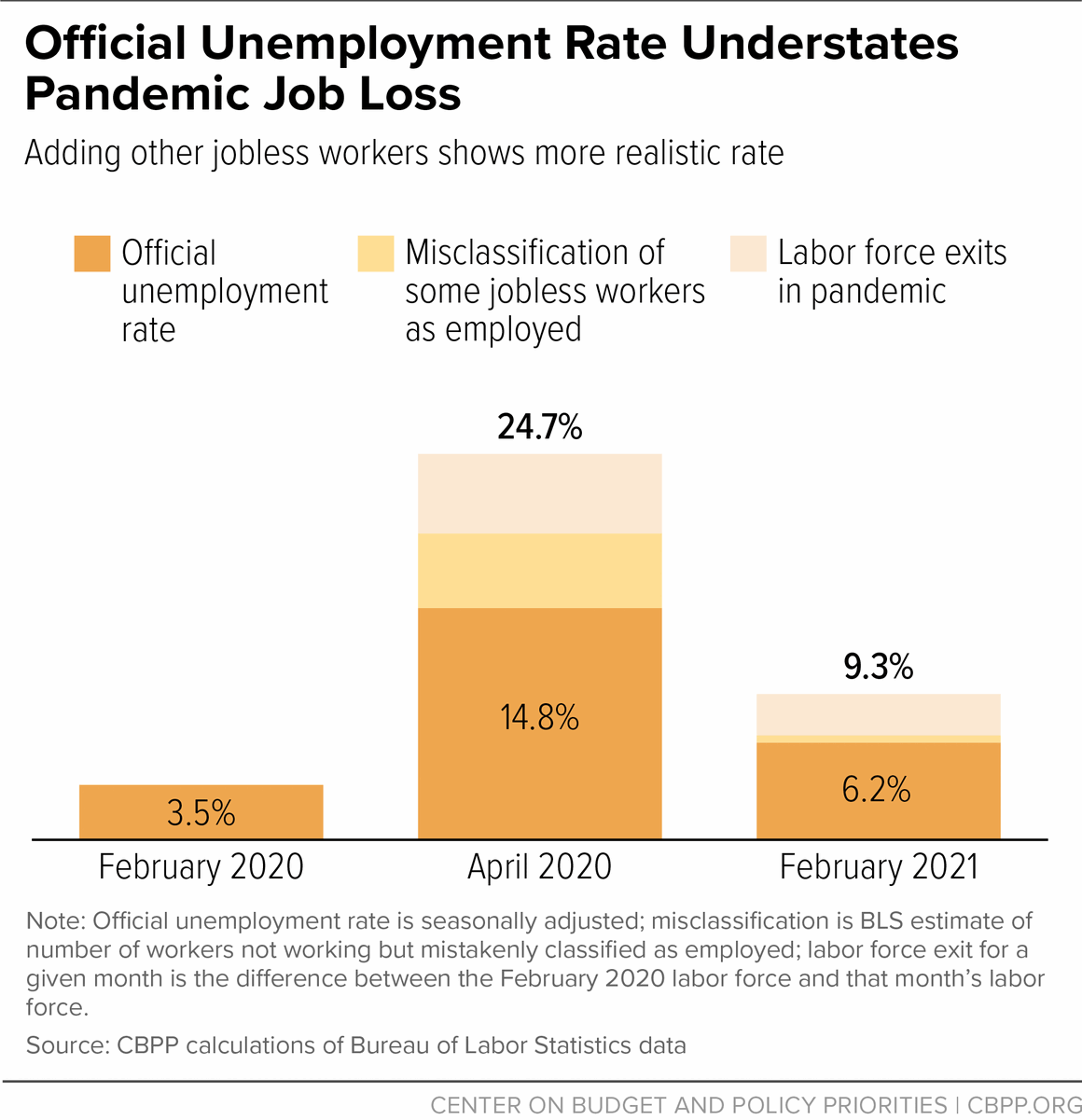

In February 2021 there were still 9.5 million fewer payroll jobs than in February 2020. (See Figure 1.) Black and Latino unemployment stood at 9.9 percent and 8.5 percent, respectively, well above the white unemployment rate of 5.6 percent — which itself is too high. Unemployment is also higher among workers who were born outside the United States, which includes individuals who are now U.S. citizens.

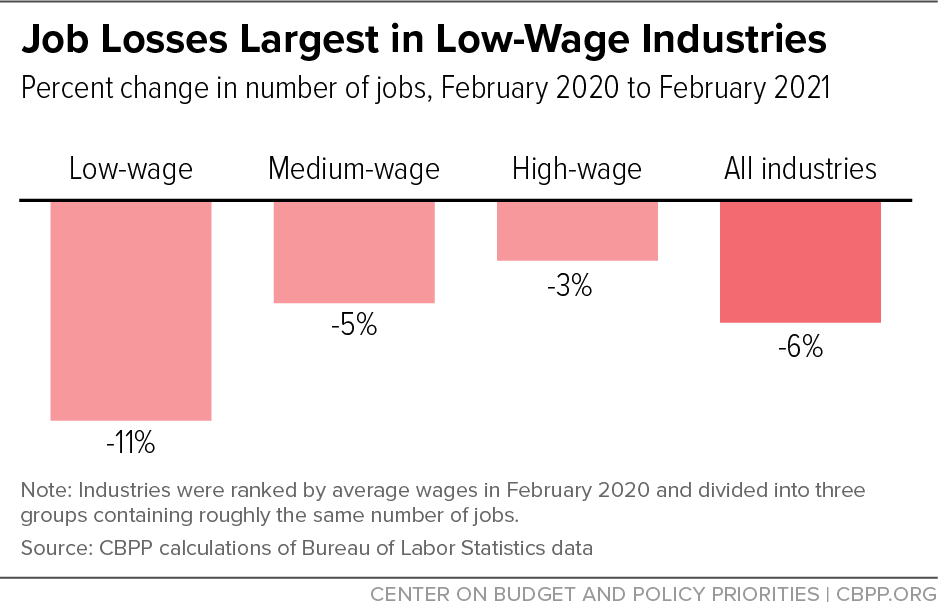

Most of the jobs lost during COVID-19 and the economic crisis have come in industries that pay low average wages, with the lowest-paying industries accounting for 30 percent of all jobs but 55 percent of the jobs lost from February 2020 to February 2021 (the latest month of Labor Department employment data). Jobs in low-paying industries were down more than twice as much between February 2020 and February 2021 (11.2 percent) as in medium-wage industries (5.1 percent) and more than three times as much as in high-wage industries (3.0 percent). (See Figure 2.)

Due to a long history of racism and discrimination and starkly unequal opportunities in education, housing, health care, and employment, Black and Latino workers are disproportionately represented in low-paying industries, a key reason why Black and Latino unemployment is so much higher than white unemployment. Workers in low-paid industries that kept their jobs were also more likely than others to work on-site rather than remotely, raising their risk of COVID-19.

The impact of joblessness goes well beyond the workers themselves who are out of work. Some 27 million people (including 6.6 million children) either were officially “unemployed” (meaning they actively looked for work in the last four weeks or were temporarily laid off) or lived with an unemployed family member in February, according to the basic monthly Current Population Survey that the Census Bureau released on March 10. But the official definition of “unemployed” understates the weakness in the labor market and the degree of hardship joblessness is causing. (See Figure 3.) The official definition of unemployed leaves out many workers who either lacked work or pay — including 4.2 million jobless workers in February who did not look for work due to COVID-19, according to the Labor Department. This includes workers who are unable to work due to their own health or the health of a family member and substantial numbers of parents, particularly mothers, who are not working because schools and child care are not fully open for in-person school and services. Also omitted are over 700,000 workers who reported that they had a job but that they were absent from work and lost pay in the last four weeks “because their employer closed or lost business due to the coronavirus pandemic,” according to our calculations.

All told, we estimate, as many as 38 million people in February, including nearly 10 million children, lived in a family in which at least one adult did not have paid work in the last week due to unemployment or the pandemic.

High Levels of Hardship

While the Rescue Plan will begin to reduce hardship as stimulus payments, rental assistance, the Child Tax Credit, and other forms of aid begin to reach households, as of February 2021, Census data show tens of millions of households struggle to pay their bills, with hardship rates particularly high among households of color and households with children.

Since late August, the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey has provided data on the number of adults struggling to cover usual household expenses such as food, rent or mortgage, car payments, medical expenses, or student loans — and it paints a distressing picture of ongoing hardship.

Nearly 81 million adults (35 percent of all adults in America) reported between February 17 and March 1 that their household found it somewhat or very difficult to cover usual expenses in the past seven days, and that figure rises to 41 percent for adults living with children. Black and Latino adults reported higher rates of difficulty covering expenses: 53 percent and 49 percent, respectively, compared to 30 percent for Asian adults and 27 percent for white adults. Grouped together, 47 percent of American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and multiracial adults reported difficulty paying for usual expenses (these groups are reported on together because the sample size for each group individually is too small).

An estimated 42 percent of children live in households that have trouble covering usual expenses, according to our analysis of the Pulse survey data collected from February 3 to 15. They include 61 percent of children in Black households, 52 percent of children in Latino households, 34 percent of children in Asian households, and 33 percent of children in white households.

More specifically:

-

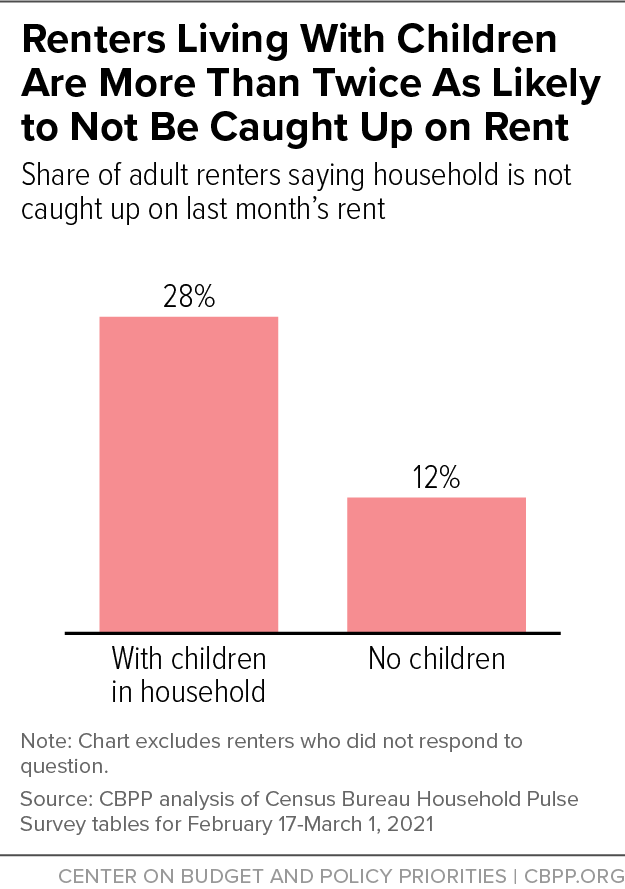

Rent or mortgage. An estimated 13.5 million adults living in rental housing — nearly 1 in 5 adult renters — were not caught up on rent, according to data collected from February 17 to March 1. Renters of color were likelier to report that their household was not caught up on rent: 33 percent of Black renters, 20 percent of Latino renters, and 16 percent of Asian renters reported not being caught up on rent, compared to 13 percent of white renters. The rate was 22 percent for American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and multiracial adults, who are grouped together due to data limitations.

In addition, 28 percent of renters who are parents or otherwise live with children reported that they were not caught up on rent, compared to 12 percent of adult renters who are not living with anyone under age 18. (See Figure 4.) Children in renter households also face high rates of food hardship: over 1 in 4 children in rental housing live in a household that didn’t have enough to eat, according to data for the period February 3 to 15 (the latest available data to make these estimates). And 4 in 10 children in rental housing live in a household that isn’t getting enough to eat or isn’t caught up on rent.

While households that make mortgage payments typically have higher incomes than renters, they, too, face difficulties, especially if they have lost their jobs or seen their incomes fall significantly. An estimated 10.3 million adults are in a household that is not caught up in its mortgage payment.

-

Food. Some 22 million adults (11 percent of all adults) reported that their household sometimes or often didn’t have enough to eat in the last seven days, according to Pulse data collected from February 17 to March 1 — which was far above the pre-pandemic rate: an Agriculture Department survey found that 3.4 percent of adults reported that their household had “not enough to eat” at some point over the full 12 months of 2019.

Adults in households with children were likelier to report that the household didn’t get enough to eat: 14 percent, compared to 8 percent for households without children. And 10 to 15 percent of adults with children reported that their children sometimes or often didn’t eat enough in the last seven days because they couldn’t afford it, well above the pre-pandemic figure. In addition, our analysis of more detailed data from the Pulse Survey from February 3 to 15 shows that 6 to 10 million children live in a household where children didn’t eat enough in the last seven days because the household couldn’t afford it.

Black and Latino adults were more than twice as likely as white adults to report that their household did not get enough to eat: 22 percent and 16 percent, respectively, compared to 7 percent of white adults. (See Figure 5.) Grouped together, American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, or multiracial adults were more than twice as likely (at 19 percent) as white adults to report that their household did not get enough to eat.

The American Rescue Plan Act

The American Rescue Plan Act will provide needed help to tens of millions of people, reduce hardship, help school districts address students’ “unfinished learning” (the learning they have missed over the last year because of disruptions to education, remote learning, and other pandemic-related issues), and bolster the economy. Along with the provisions described below, it includes a new round of economic impact (“stimulus”) payments, public health investments, more child care funding, and aid to businesses.

Helping Jobless Workers

The Rescue Plan will extend critical unemployment benefits that are helping jobless workers pay their bills and care for their families.

The December relief package reinstated a federal unemployment benefit increase, provided more weeks of benefits so that jobless workers wouldn’t lose them while the nation struggled with the current health and economic crisis, and continued the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program, which expands benefit eligibility to more jobless workers. These provisions were slated to expire in mid-March, and the Rescue Plan extends them through September 6. The early September cutoff is problematic, however. Joblessness — appropriately measured to take into account those who are out of work due to the crisis but not captured by the official unemployment rate — particularly among workers of color and workers without a college degree, will likely remain elevated in the fall. Congress must be prepared to act to extend this unemployment benefit before September 6 if joblessness — overall or among particular groups of workers for whom the recovery is lagging — remains high. It is important to note that even if the labor market overall has rebounded considerably, extended jobless benefits may still be warranted if joblessness remains elevated among particular groups of workers. The early September cutoff date means that Congress will need to act before the end of the fiscal year to avert a cutoff, which would hurt workers and their families and cause needless administrative headaches for state unemployment programs still struggling to effectively administer these expanded benefit programs.

Helping Households Struggling to Make Ends Meet

-

Housing. The Rescue Plan includes critical housing assistance for millions who are struggling to pay rent and avoid eviction, and badly needed funds for communities to address homelessness during the pandemic.

The housing and homelessness funding in the Rescue Plan will supplement $25 billion in emergency rental assistance from December’s relief package. The Rescue Plan builds on these efforts by providing an additional $21.6 billion in emergency rental assistance; this $46.6 billion total investment will enable communities nationwide to help approximately 4 to 6 million households avert eviction and housing instability. The Rescue Plan also includes substantial resources to mitigate the devastating effects of homelessness. The Department of Housing and Urban Development’s recently released 2020 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report shows that homelessness — especially unsheltered homelessness — was increasing at an alarming rate even before the pandemic, and communities across the country report that the pandemic has made things even worse. The Rescue Plan includes $5 billion for approximately 65,000 Housing Choice Vouchers to serve people experiencing or at risk of homelessness, and $5 billion in HOME Investment Partnerships Program funding to develop approximately 20,500 units of affordable or supportive housing for people experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness. These investments will enable communities to put thousands of individuals and families who have been extremely hard hit by the public health and economic impact of the pandemic on the path towards recovery.

The Rescue Plan also includes housing resources for other highly impacted communities, including $750 million in housing aid for tribal nations and Native Hawaiians; $139 million for rural housing assistance; $100 million for housing counseling services for renters and homeowners; and $20 million to support fair housing activities. It also provides $10 billion to help homeowners who are experiencing financial hardship due to COVID-19 maintain their mortgage, tax, and utility payments and avoid foreclosure and displacement.

Helping those experiencing homelessness secure housing and helping those behind on rent catch up and avert eviction are critical to fighting the pandemic itself (COVID can be more easily transmitted in congregate shelters, on the streets, or in over-crowded housing), stabilizing families, and preventing children from disruptive moves and school changes. Providing rental assistance to families to prevent evictions and homelessness — which are associated with increased likelihood for children with cognitive and mental health problems, physical health problems such as asthma, physical assaults, and poor school performance — can also have far-reaching implications for children’s lives. In addition, rental assistance reduces families’ chances of having a child placed into foster care and the frequency with which their children must change schools, and may improve test scores for some categories of children.

-

Tax credits. The Rescue Plan temporarily makes the full Child Tax Credit available to all poor and low-income children, increases the size of the Child Tax Credit, and provides an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for far more low-paid adults without minor children at home — driving a historic reduction in child poverty and providing timely income support for millions of people. The expansions apply to tax year 2021, with part of the Child Tax Credit being delivered in advance later this year (rather than being delivered next year after households file a tax return).

Prior to the expansion in the Rescue Plan, some 27 million children received a partial Child Tax Credit or no credit at all because their families’ incomes were too low. The Rescue Plan makes the full Child Tax Credit available to children in families with low or no earnings, raises the maximum credit from $2,000 to $3,000 per child (and $3,600 for children under age 6), and extends the credit to 17-year-olds. The increase in the maximum amount will begin to phase out for heads of households making $112,500 and married couples making $150,000. The Rescue Plan will lift 4.1 million additional children above the poverty line — cutting the number of children in poverty by more than 40 percent — and lift 1.1 million children above half the poverty line (referred to as “deep poverty”). Among the children that the Child Tax Credit expansion will lift above the poverty line, some 1.2 million are Black and 1.7 million are Latino.

The Rescue Plan also raises the EITC for adults in low-paid jobs who are not raising children at home and now get only a tiny credit or no credit at all. It raises the maximum EITC for these “childless workers” from about $540 to about $1,500, raises the income cap for them to qualify from about $16,000 to at least $21,000, and expands the age range of those eligible to include younger adults aged 19-24 who aren’t full-time students and those 65 and over. That will provide timely income support to over 17 million people who work for low pay, including the 5.8 million childless workers aged 19-65 (excluding full-time students aged 19-23) who are now the lone group that the federal tax code taxes into, or deeper into, poverty because their payroll taxes (and, for some, income taxes) exceed any EITC they receive.

These expansions will help push against racial disparities. Before the Rescue Plan, about half of all Black and Latino children were getting only a partial Child Tax Credit or no credit at all because their families’ incomes were too low to qualify for the full credit. That design flaw in the Child Tax Credit came on top of long-standing employment discrimination, unequal opportunity in education and housing, and other factors that leave more Black and Latino households struggling to make ends meet. Similarly, the 5.8 million childless adults in low-paid jobs who are taxed into, or deeper into, poverty are disproportionately people of color: about 26 percent are Latino and 18 percent are Black, compared to 19 percent and 12 percent of the population, respectively.

In two historic firsts, the Rescue Plan also extends a federal supplement to help Puerto Rico expand its own EITC (which went into effect in 2019) and corrects a long-standing limitation by which only families with three or more children in the Commonwealth can claim the Child Tax Credit. It marks the first time that Puerto Rico receives federal EITC dollars since the EITC was established in the continental U.S. nearly half a century ago, and the first time that families with one or two children may claim the Child Tax Credit since it was established in the late 1990s. Both credits will provide a crucial boost to hundreds of thousands of families in Puerto Rico, whose poverty rates of 43 percent overall and 57 percent for children are among the nation’s highest.

-

Food assistance. The Rescue Plan extends and expands nutrition assistance to help address today’s extraordinarily high levels of hunger and hardship.

The Rescue Plan extends, through September, a 15 percent increase in SNAP benefits from December’s relief package that was slated to expire in June. It lets states continue, through the summer and through the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency, the Pandemic EBT (P-EBT) program, which provides grocery benefits to replace meals that children miss when they do not attend school or child care in person. Extending this benefit through the summer is important, providing a bridge to help families until school reopens, hopefully fully in-person, for the next school year. Food insecurity among children often rises in the summer when they aren’t able to access school meals; these benefits will help families afford food over the summer.

The Rescue Plan also provides funds to modernize the WIC nutrition program for low-income women, infants, and children, support innovative service delivery, conduct robust outreach, and temporarily raise the amount of fruit and vegetables that participants can get. These steps will improve a critical program that boosts health and cognitive outcomes for children but that served fewer individuals in fiscal 2020 than the prior year despite a surge in food hardship during the pandemic. And it adds $1 billion to the capped block grants for food assistance that Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands receive instead of SNAP, enabling them to better meet their residents’ food needs over the next several years.

-

Help for families with the lowest incomes. The Rescue Plan includes $1 billion for a Pandemic Emergency Assistance fund to enable states, tribes, and territories to help families with the lowest incomes cover their additional pandemic-driven expenses and avert eviction and other hardships. These are funds states can use flexibly to fill in gaps left by other investments.

States, territories, and tribes can use the new fund to provide households with non-recurrent, short-term benefits — that is, benefits that: (1) address a specific crisis or episode of need; (2) don’t meet recurring or ongoing needs; and (3) don’t extend beyond four months. States could direct funds to the families that most need them, and states need not limit payments to families receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance. States can use the funds, for instance, to help families that don’t get emergency housing assistance pay their back rent and avoid eviction, or help families fleeing domestic violence cover their moving costs and initial rental payments.

Expanding Health Care

The Rescue Plan will make comprehensive health coverage more affordable and accessible for millions of people during the current crisis.

Comprehensive health coverage is important under any circumstance because it improves people’s access to care, financial security, and health outcomes. But preserving and extending coverage is even more important now, during COVID-19 and its economic fallout, because it will shield families from financial hardship and support public health efforts, easing people’s access to testing, treatment, and vaccines. Prior to the Rescue Plan, the relief measures that policymakers enacted in 2020 did not extend health coverage or make it more affordable.

To make marketplace coverage more affordable, the Rescue Plan eliminates or vastly reduces premiums for many people of low or moderate income who enroll in plans through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces, and it provides new help to people with somewhat higher incomes who face high premiums. These provisions lower premiums for most current marketplace enrollees and expand coverage to 1.3 million people who would otherwise be uninsured, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The Rescue Plan improves affordability and reduces the number of uninsured people in three other ways: (1) protecting marketplace enrollees, especially those whose income fluctuated last year, from having to repay large portions of their federal premium tax credits; (2) making it easier for those getting unemployment benefits to afford coverage; and (3) assisting people who recently lost their job and want to continue their current coverage to afford what’s known as “COBRA” coverage through September.

The Rescue Plan also increases financial incentives for the 14 states that have not implemented the ACA’s Medicaid expansion to do so, which would provide critical coverage to nearly 4 million uninsured people (if all states adopted the expansion). And it will strengthen Medicaid coverage in other ways — for instance, with higher federal matching funds to help more seniors and people with disabilities get services in the community instead of nursing homes, a new state option to extend Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program coverage to 12 months after childbirth for postpartum people, and an option to cover uninsured people for testing, vaccines, and treatment of COVID-19.

Boosting States, Strengthening Education

The Rescue Plan provides $350 billion to help states, localities, tribal governments, and territories cover costs generated by COVID-19 and the economic fallout and offset revenue losses, which are substantial in some places.

The pandemic has imposed significant costs on state and local governments to fight the virus, deliver services despite public-health-related restrictions, and help struggling people and businesses. These costs will continue in the months ahead even if the pandemic is ultimately contained. Many millions of people, particularly low-income people and people of color, are struggling with hunger, have large unpaid rent bills, face mental health challenges as a result of the pandemic, or are enduring other forms of hardship. Millions of children effectively have a year of learning they need to regain that will require time and resources — such as investments in longer school days, extended school years, and intensive tutoring for multiple years — to address. Households, as well as millions of struggling small businesses, will require support to make it through the pandemic and recover from its harm. While federal support provides important direct assistance, state and local governments will need to deliver a wide range of localized supports and services and sustain them over a long period of time.

While the pandemic’s hit on state revenues has been less than feared, revenues in most states remain below pre-pandemic projections, and some states have experienced severe revenue losses. Most cities and counties received no direct federal aid prior to the Rescue Plan, and revenue sources they depend upon — including hotel and restaurant charges, parking fees, and business license fees — have been hit particularly hard. Many tribal governments are dependent on casinos and other forms of revenue that have been hit especially hard.

Along with the other costs cited above, states and the other jurisdictions also can use the additional federal funding to help pay for long overdue investments in broadband (a need that COVID-19 particularly exposed) and for clean water and sewer infrastructure projects, as well as to provide “premium pay” to essential public workers. In addition, the Rescue Plan provides a separate $10 billion to states, territories, and tribal nations for capital projects. To help ensure that states spend the federal aid as intended, the Rescue Plan requires that any state or territory adopting net tax cuts lose an equivalent amount in federal aid. States remain free to enact tax cuts, but they may lose an equivalent amount of aid if the Treasury Department determines that they used the aid directly or indirectly to fill in for the tax cuts.

With states and localities facing so many other demands on their resources, the Rescue Plan also provides $123 billion in new, mostly flexible funds that school districts can spend through the 2023-24 school year to address the pandemic and its effects on student learning. This is the largest-ever one-time federal investment in K-12 education, but entirely appropriate in light of school funding needs.

Historically, K-12 schooling has been funded overwhelmingly by states and localities; they currently provide 92 percent of funding, with the federal government providing the rest. COVID-19, however, forced states to cut funding and created enormous financial and educational challenges that states and localities will be hard pressed to meet over the next several years without federal assistance. K-12 funding comprises about 26 percent of state budgets and, in the absence of the general fiscal aid and the education-specific funding, many states would have found it challenging to shield school funding from cuts. Even before COVID-19, schools endured years of inadequate and inequitable funding. Some 15 to 20 states were still providing less funding for K-12 schools when the pandemic hit than before the Great Recession of a decade ago in per-pupil, inflation-adjusted terms. When COVID-19 hit, schools were employing about 77,000 fewer teachers and other workers while educating about 1.5 million more children.

The CARES Act provided $13.2 billion for K-12 education and December’s package provided another $54 billion, but schools will need far more to pay for distance learning, safe in-person instruction, caring for students’ physical and mental health, and, most significantly, helping children catch up from substantial unfinished learning. Schools need to close the “digital divide” so all students and teachers have access to devices and connectivity. They can also use the funding to safely operate in-person schools, which may require more buses and drivers and additional classrooms and teachers to maintain social distancing. A quarter of schools have no full- or part-time nurse, and most schools lack counselling support to help students navigate the mental-health challenges stemming from the pandemic, its economic fallout, and now the return to school for many students.

But beyond addressing the costs of operating remotely and in person, the Rescue Plan’s funds will enable school districts to make critical investments to address widespread unfinished learning that the pandemic and remote learning have caused. Students on average will likely lose nine months of learning by the end of the 2020-21 school year, McKinsey & Company estimates, and students of color may well lose a full year on average. With the requisite resources, schools can lengthen school days and the school year and invest in high-quality tutoring to help students — over the course of the next couple of years — recover what they have lost. The costs of addressing all these needs could easily top $100 billion over the next few years, based on estimates from the Learning Policy Institute and McKinsey. Along with the $123 billion, the Rescue Plan includes “maintenance of equity” provisions that require states to avert funding cuts to schools and school districts with high numbers of poor children.

Transit

The Rescue Plan provides $30.4 billion to transit agencies, primarily by formula grant, to support operating costs and thereby prevent cuts in transit services and layoffs of transit workers.

Transit agencies are facing severe financial stress, as ridership of buses and rail has declined during the pandemic, reducing revenues. Yet public transportation is a lifeline for those without access to cars who need to get to work, including essential workers and others who are not able to work from home or who need to travel to fulfill basic needs, like seeing the doctor or going to the grocery store. Scaling back mass transit services and laying off transit workers not only risks leaving millions of riders stranded, but also would leave transit agencies poorly positioned to support a robust recovery as the pandemic recedes.

The assistance provided by the Rescue Plan should prevent damaging cuts, allow public transit to continue needed services, and respond quickly as ridership increases with a stronger economy. Public transportation is particularly important to low-income communities and communities of color, even as decades of policy choices have left many of these communities under-resourced and with poorer access to public transit. While it is crucial that these communities be protected from cuts in services, policymakers should also focus on designing further investments in public transit so that they have the potential to increase access to jobs and extend economic opportunity to underserved communities.[1]

Our Underlying Policy Gaps Necessitated Large, Stopgap Measures

While the American Rescue Plan Act, along with the relief measures of 2020, will provide substantial help to tens of millions of people who are struggling to make ends meet and access health care during this crisis, we should ask why such large-scale stopgap measures were needed in the first place.

The reason is clear: COVID-19 and its economic fallout have exposed glaring weaknesses in our economy and our public policies that leave too many people unprotected in bad times and too many unable to fully benefit in good times. Before the crisis began, our unemployment insurance system was very weak; we were providing inadequate support for the millions of Americans who struggle every day to pay rent, buy food, and afford other basics; and 29 million people lacked health coverage. We tolerate very high levels of poverty and hardship when households fall on hard times, whether because of a recession or another national crisis, or because, as often occurs, an employer goes out of business or a family member is ill and can’t work. The nation would need fewer stopgap measures during hard times if we had stronger permanent policies in place to help households and workers when they need it.

Other wealthy nations do far more to invest in children, to support workers and their households both when they are working for low pay and when they are out of work, to assure more adequate minimum wages, and to ensure that everyone can access health care. The United States can afford these kinds of policies as well. Failure to make these kinds of investments and policy changes has real costs, to individuals and the nation as a whole. Research shows that poverty and the hardships that come with it — housing instability, food insecurity, and high levels of family stress that can become toxic to developing children — can have negative long-term impacts on children’s health, education, and earnings. There are negative impacts on adults, as well, when they don’t have enough to eat, face eviction, and don’t have access to health care.

The Rescue Plan addresses many of these key policy gaps but only temporarily, so much of our progress will reverse once its provisions begin to expire — unless policymakers take steps to extend key provisions and make longer-term investments in key areas. The Rescue Plan also makes crystal clear that we can address the challenges of poverty and hardship if we have the will do so.

Building a More Equitable Economy

The President and Congress will soon have a historic opportunity to build toward an equitable recovery where all children can reach their full potential, where workers in low-paid jobs and those with fewer job prospects have the supports to help them meet their needs and get ahead, and where everyone has access to affordable health coverage. Achieving these goals requires attacking long-standing disparities in our nation, deeply rooted in racism and discrimination, that have led to starkly unequal opportunities and outcomes in education, employment, health, and housing.

This spring and summer, policymakers will work on another substantial legislative package, this one framed around the nation’s recovery. As we invest in infrastructure and take steps to address climate change, we also must invest in an equitable recovery that enables everyone to share in its benefits.

If policymakers don’t take this opportunity to create a more equitable recovery, and instead craft a legislative package focused only on physical infrastructure and climate technology, future economic growth may be somewhat higher than if no package were enacted at all, but millions of households will see little benefit from that growth. Most people working in low-paid jobs will continue to struggle to make ends meet, those who lose their jobs will not have help to tide them over, tens of millions of people will still lack health coverage, and child poverty and its attendant hardships will remain high, robbing children of the future they deserve.

Housing investments should be a key component of a recovery package. First, housing vouchers should be expanded toward the goal of ensuring that all households that need rental assistance can receive it. Housing vouchers lower the likelihood that a low-income family lives in crowded housing (by 52 percent) or is homeless (by 74 percent) and reduce their frequency of moving (by 35 percent)[2] — important steps for reducing school disruption and other harmful outcomes for children. (See Figure 6.) But just 1 in 4 eligible households receive any federal rental assistance due to limited funding. Providing vouchers to all eligible households would lift 9.3 million people above the poverty line and cut the child poverty rate by one-third, according to a recent Columbia University study. [3] It also would narrow the gap in poverty rates between white and Black households by over a third and the gap between white and Latino households by nearly half.

As the economy recovers, high housing costs will continue to create economic instability and hardship for millions of low-income renters, increasing their risks of housing instability and homelessness and undercutting their children’s chances of succeeding over the long term. Housing vouchers make rent affordable for people in low-paying jobs and are highly effective at reducing homelessness. They also serve as an important hedge against housing instability and financial hardship during recessions because the voucher subsidy rises when a household’s income falls due to a lost job or work hours.

Investments in renovating and building affordable housing also have an important role to play, particularly in tight housing markets. Carefully designed investments of this type can make rents more affordable for low-income households, reduce homelessness, improve residents’ living conditions and health outcomes, and reduce racial inequities in housing opportunities and housing quality. They also generate jobs and construction activity and can lower greenhouse-gas emissions by making developments more energy efficient. In making such investments, policymakers should place a high priority on renovating the existing public housing stock, creating housing options for people experiencing homelessness, and providing substantial additional resources for affordable housing development through the Indian Housing Block Grant and National Housing Trust Fund.

However, supply interventions alone will not address the affordable housing crisis. Many communities have ample supply of housing but housing remains unaffordable for people with modest incomes. Additionally, supply interventions often do not produce housing with rents that are low enough to be affordable for households with incomes near or below the poverty line — the group that makes up most of the renters confronting severe housing affordability challenges[4] — unless those households also receive a voucher or similar rental assistance. Voucher expansion is therefore crucial to ensuring that a recovery package reaches those who most need help to afford stable housing.

Beyond housing, there are other key investments the nation needs to make to build toward an equitable recovery. These include:

- Help for people in low-paid jobs and people out of work. Workers in low-paid jobs struggle to make ends meet, face high child care costs, and often receive no help from unemployment insurance when they lose a job. The recovery package can take important steps to help these workers, including by shoring up our unemployment insurance system so more jobless workers are covered and benefits are more adequate; expanding access to high-quality, affordable child care; making the Rescue Plan’s EITC expansion for low-paid workers without children permanent; creating a paid leave program so workers can afford to take time off for health issues or caregiving responsibilities; and investing in job training and subsidized jobs to help people succeed in the labor market and have opportunities to work.

- Key investments for children. There is strong evidence that poverty, and the hardships that come with it, shortchange children’s long-term health and education outcomes, and that investments in children can improve their trajectories markedly. These include investments such as making the Rescue Plan’s Child Tax Credit expansion permanent, strengthening nutrition programs, and investing in high quality child care and early education.

- Expanded access to health coverage. The United States can get far closer to universal health coverage by making marketplace coverage more affordable, allowing more people to purchase marketplace coverage when employer coverage isn’t affordable, and strengthening Medicaid coverage and ensuring that individuals are able to keep their coverage for a full year.

The United States can afford to make these investments. After two decades of tax cuts, we should start by rebuilding our tax code so that the wealthiest households and large, profitable corporations contribute in a fair way while also rebuilding the IRS so that the taxes owed are collected. This would raise substantial revenue and help fund critical investments that promote broadly shared economic growth, broaden opportunity, and improve well-being among those not already well-heeled.

Conclusion

Over the last year, the President and Congress took bold action, culminating in this year’s American Rescue Plan Act, to help tens of millions of individuals and families that were struggling in the midst of COVID-19 and its economic fallout. The legislation and its likely impact show that we know how to reduce poverty and hardship and how to narrow economic and racial inequities.

But, like the CARES Act and Families First Act of last spring and the relief package of December, the Rescue Plan Act provides only temporary relief. The progress we will make under it in helping workers and their families, in reducing poverty and hardship, in narrowing economic and racial inequities, and in expanding access to health care will largely unravel as its provisions expire.

As the President and Congress turn to economic recovery legislation this spring and summer, however, they have a historic opportunity to make permanent progress by addressing the underlying weaknesses in our economy and our public policies that made the stopgap measures of the last year so necessary.

Tracking the COVID-19 Economy’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships

End Notes

[1] Chye-Ching and Roderick Taylor, “Any Federal Infrastructure Package Should Boost Investment in Low-Income Communities,” CBPP, updated June 28, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/any-federal-infrastructure-package-should-boost-investment-in-low-income.

[2] Michele Wood, Jennifer Turnham, and Gregory Mills, “Housing Affordability and Family Well-Being: Results from the Housing Voucher Evaluation,” Housing Policy Debate, Vol. 19, No. 2, January 2008, pp. 367-412.

[3] Sophie Collyer et al., “Housing Vouchers and Tax Credits: Pairing the Proposals to Transform Section 8 with Expansions to the EITC and Child Tax Credit Could Cut the National Poverty Rate by Half,” Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy, October 7, 2020.

[4] Seventy-four percent of renter households that paid more than half their income for housing in 2018 had “extremely low-incomes,” defined as incomes below the higher of the federal poverty line or 30 percent of the local median income. (CBPP analysis of 2018 American Community Survey and 2018 HUD income limit data.)

More from the Authors