A new proposed rule from the Trump Administration’s Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) would make it significantly harder for families to fight housing policies and practices that restrict access to housing or perpetuate disparities for certain people.[1] The rule would dramatically change the standards by which a person or entity, including the federal government, can sue to end discriminatory housing practices through what is known as a “disparate impact” claim, thereby weakening the Fair Housing Act (FHA), a Civil-Rights-Era federal law protecting people who have historically experienced racism and discrimination that limit their housing options. The proposed changes would overwhelmingly tip the scales in favor of landlords and other defendants, letting them keep policies and practices that prevent people of color, women, families with children, people with disabilities, and others from having the fair access to housing that the FHA was intended to protect. This is in direct conflict with HUD’s statutory obligation to affirmatively further fair housing.[2]

Disparate impact refers to policies or practices that seem neutral or fair but in practice — either intentionally or unintentionally — negatively and disproportionally affect certain groups of people. In a housing context, disparate impact claims are a tool for enforcing rights under the FHA, which bans housing discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, familial status, disability, and religion.[3] The current rule allows people to bring legal action to stop policies that harm them, for example a landlord requiring tenants to work a certain number of hours a week, which on its face may not seem discriminatory but which reduces housing choice for protected groups, in this case people with disabilities who often work part time to accommodate their health needs.

The Administration’s proposed rule would severely limit plaintiffs’ ability to both bring and win disparate impact claims. It would thereby increase the challenges that low-income people of color, individuals with disabilities, and others such as families with children face finding a place to live. In addition, this proposal could empower communities to restrict these renters and new affordable housing units to certain neighborhoods, limiting the housing choices of those whom the FHA is supposed to protect and likely perpetuating the concentration of low-income renters of color and affordable housing developments in communities that face chronic underinvestment.

While the proposed rule affects many housing market stakeholders, this report primarily describes the impact on renters, especially those receiving federal rental assistance, and rental properties, primarily those financed using the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program. Among renters, we highlight the challenges for renters of color and renters with disabilities because these two FHA-protected groups are most likely to report experiencing housing discrimination, evidence shows.[4]

For more than four decades, two legal tools have been used to protect against housing discrimination: (1) disparate treatment claims, which challenge clearly intentional discrimination, such as overt racism, and (2) disparate impact claims, which challenge policies that may seem neutral or fair but in practice disproportionately deny housing to members of a protected class. HUD’s proposed rule would make it harder for people protected under the FHA to bring forward successful disparate impact claims. The proposed rule does this by changing the standard used to determine what a renter (or other plaintiff) must do to bring forward and win their case.

In 2013, HUD finalized a rule that lays out the current disparate impact standard, which codified the standard courts most commonly used for decades.[5] When someone files a discrimination claim, they first have to establish what is called a prima facie case, that is, the plaintiff brings forward enough information that, if all true, could win them the case; this ensures that a real issue is at hand that deserves the court’s attention. Only after the plaintiff establishes a prima facie case can the discovery process start, during which both parties request information from each other that they will then use as evidence to prove (or disprove) disparate impact discrimination and win their case.

The proposed rule would turn the prima facie standard into a difficult five-step process that would be nearly impossible for most renters to meet. In practice, the five steps would require renters to have information about the defendant that they almost certainly wouldn’t obtain until the discovery phase, which now they won’t reach, putting renters and other plaintiffs in a double bind. For instance, plaintiffs would have to imagine possible motives behind the defendant’s discriminatory policy or practice and be able to determine that those motives don’t justify the policy, all before being able to request evidence from the defendant.

Even if a plaintiff could establish a prima facie case under HUD’s proposed rule, they would still face new hurdles to winning their case compared to the time-honored standard. Currently, after the plaintiff passes that initial prima facie test, the defendant gets a chance to show they have a legitimate reason for using the policy or practice. And if the defendant succeeds, the plaintiff can still win if they can point to a less discriminatory policy or practice that could achieve the defendant’s goal. The proposed rule superficially keeps these steps in place, but makes it much easier for the defendant to show they have a legitimate reason for the policy and much harder for the plaintiff to point to an alternative policy.

For example, the plaintiff would have to find an alternative policy that not only “serve[s] the defendant’s identified interest in an equally effective manner” but also does so “without imposing materially greater costs on, or creating other material burdens for, the defendant.”[1] (The rule does not define “materially greater costs” and it could be interpreted to mean that even a relatively modest cost increase would be reason enough to allow a discriminatory policy to remain in place.) This values profit over people’s right to fair housing, making it much more difficult for plaintiffs to identify an alternative practice that meets this standard, and far likelier that defendants would be allowed to continue using policies that clearly harm members of a protected class.

In addition to making it harder for a plaintiff to prove their case, HUD’s proposed standard would create several new ways for defendants to shield themselves from liability even if the plaintiff proves that the policy or practice disproportionately harms members of a protected class. For example, defendants could avoid liability if they relied on a model or algorithm that was “produced, maintained, or distributed by a recognized third party that determines industry standards.” But even sophisticated algorithms that seem neutral can cause discriminatory effects, emerging evidence suggests. Researchers, for instance, are raising concerns that automated hiring practices that use algorithms can cause racial and gender disparities in hiring.[6]

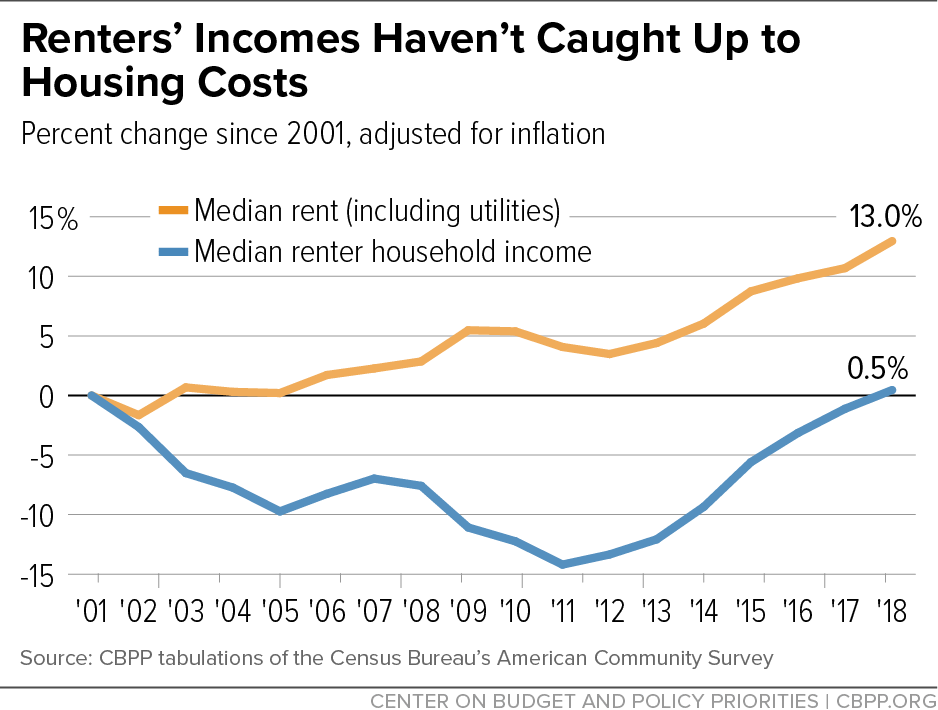

Low-income renters already have limited affordable housing options. Renters’ incomes have long trailed rising housing costs; between 2001 and 2018, after adjusting for inflation, median renter household income rose by just 0.5 percent while rents rose 13 percent.[7] (See Figure 1.) Being denied access to housing due to racist or discriminatory practices narrows renters’ potential housing pool even more. With fewer options, families may have to accept substandard housing or pay more for rent than they can afford, threatening their economic and educational outcomes and risking housing stability and even homelessness.

Racist and discriminatory practices — even those that seem neutral but have discriminatory impacts — affect where families find housing they can afford, which can harm their current and future outcomes. Studies show that where families live largely determines the quality of their children’s schools, the safety of their communities, and access to fresh and affordable food.[8] Housing location also affects adults’ access to well-paying jobs; living far from work can raise commuting costs and cause longer periods away from home. If communities enact policies that restrict affordable housing developments or if landlords can refuse renters who use rental subsidies to pay rent, it can effectively prohibit low-income people of color and others whom the FHA protects from living in certain neighborhoods. This limits renters’ choice and may prevent them from experiencing the positive mental and physical health effects that living in high-opportunity neighborhoods has been shown to promote.[9] Living in a neighborhood that doesn’t meet children’s needs can also limit their potential.[10] People, especially children, have difficulty stabilizing their lives and finding future success when they face housing instability, live in substandard housing, or live in housing that is not in communities that best meet their needs.[11]

The Fair Housing Act explicitly prohibits landlords and others from refusing to rent to members of protected classes and from treating members of protected classes differently “in the terms, conditions or privileges” of a rental unit, and includes several other explicit protections for renters.[12] The federal, state, and local agencies that fund and administer federal affordable housing programs also have an obligation under the Fair Housing Act to affirmatively further fair housing, in recognition that “neutral” policies are not enough to reverse the harm done by discrimination to protected classes of people. Housing discrimination, including in the rental market, is often disguised or difficult for renters to recognize.[13] For example, if a landlord turns away an African American renter because they have an old criminal conviction and the landlord has a blanket ban on tenants with any prior convictions, the renter might not know that their fair housing rights were likely violated because the ban has disparate impact on African Americans.

Disparate impact claims “play an important role in uncovering discriminatory intent” and help “counter unconscious prejudices and disguised animus” as well as ending policies and practices that, while seemingly neutral and perhaps without discriminatory intent, have harmful effects on members of a protected class, the U.S. Supreme Court has noted.[14] By making it nearly impossible to bring or win disparate impact claims, the proposed rule undermines FHA by not protecting people who have historically faced racism and discrimination and undercutting government entities’ obligation to further fair housing protections.

Discrimination against renters is by far the most commonly reported form of housing discrimination, representing nearly 90 percent of all housing discrimination complaints filed with private fair housing organizations and federal, state, and local government agencies in 2017.[15] Low-income renters, who are more likely to struggle to afford rent, are also more likely to be members of certain protected classes. (See Table 1.)

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

Total U.S. Population |

Low-Income Renters |

Receiving HUD Rental Assistance |

Receiving Housing Choice Vouchers |

| Total Individuals |

325,719,000 |

62,710,000 |

9,735,000 |

5,337,000 |

| Share in these protected classes: |

| Living with children |

49% |

59% |

62% |

70% |

| Female |

51% |

54% |

63% |

63% |

| Latinx/Hispanic |

18% |

30% |

20% |

19% |

| Black, non-Hispanic |

12% |

23% |

47% |

51% |

| Living with a disability |

13% |

16% |

21% |

23% |

| Born outside the U.S. |

14% |

19% |

- |

- |

Disability discrimination is the most frequently reported kind of housing discrimination in fair housing complaints, followed by racial discrimination.[16] Fair housing testing also shows that discrimination remains prevalent. For instance, a 2017 study that HUD commissioned found that people with mental-health-related disabilities faced significant discrimination in the rental market compared to people without these disabilities.[17] And Black voucher holders who called a landlord about a prospective unit were significantly less likely to end up viewing that unit compared to voucher holders of other racial groups, a recent study of 128 Boston-area families using federal vouchers found.[18]

The Housing Choice Voucher program is the largest federal rental assistance program, helping more than 5 million people in over 2 million households afford a place to live. As the name implies, it is designed to give families choice about where they live by helping them pay for modestly priced housing that they find in the private market. It has several ways it allocates resources to people who qualify for housing assistance. The largest subset of resources are tenant-based vouchers, meaning the rental subsidy is tied to the individual or family instead of a physical rental unit, giving families more choice about which neighborhoods to live in. In its last major reform of the Housing Choice Voucher program, Congress made explicit that the program is intended to “promote homes that are affordable to low-income families in safe and healthy environments,” in part by “increas[ing] housing choice for low-income families.”[19] But the proposed rule’s restrictions on disparate impact claims would likely limit the voucher program’s effectiveness in fulfilling this purpose.

And, evidence shows that the Housing Choice Voucher program does indeed change housing options for families, though far more progress needs to be made. Low-income Black, Hispanic, Native American, and Pacific Islander children in families with housing vouchers are more likely to live in low-poverty neighborhoods than their counterparts without a housing voucher.[20] In metropolitan areas, however, most families with children that have vouchers, especially families of color, still live in “minority-concentrated” neighborhoods.[21] Living in a neighborhood with a large population of people of color is not problematic in and of itself. Indeed, there are high-opportunity, low-poverty neighborhoods meet HUD’s criteria for “minority-concentrated.”[22] But nearly 80 percent of metropolitan neighborhoods that meet the criteria for high poverty and low opportunity also meet HUD’s definition of “minority-concentrated.” And many families, especially families of color or others protected under the FHA, face challenges to using their vouchers in the neighborhood of their choice. “[T]he data suggest that black voucher holders experience greater challenges than other racial groups with regard to discrimination by property owners in higher-opportunity neighborhoods during housing search,” one study found.[23] While improved policies and targeted funding could ease some of these barriers, some are rooted in policies and practices that have discriminatory effects and that have been challenged as violating the FHA using disparate impact claims.

For instance, some public housing agencies administering vouchers have implemented preferences for residents already living in their communities. (Households may apply for housing vouchers in communities they do not currently reside in, but these residency preferences can effectively lock them out of both vouchers and those communities.) When housing agencies in white communities with lower poverty rates use residency preferences, they can prevent people of color from participating in the local voucher program (and gaining access to those communities), thereby creating a disparate impact on people of color and reinforcing segregation. Claims that such residency preferences disparately impact potential voucher holders on the basis of race have led to several settlements that eliminated or modified the use of residency preferences.[24]

Participants in the Housing Choice Voucher program may face greater difficulty in finding a home to rent using their voucher if disparate impact claims become harder to bring and win. Individuals and families already face significant challenges using their vouchers. It can be time consuming and difficult to locate available housing units, particularly in tight housing markets with relatively few vacancies. HUD’s proposed rule would likely heighten the use of policies that have a discriminatory impact, such as unnecessary restrictions (known as occupancy standards) that limit the number of people who can live in a rental unit, preventing families with children from living there. This would compound existing challenges and make it more likely that families in protected classes who receive housing vouchers would be unable to use them. This in turn would limit such families’ access to affordable housing and housing choice, thereby undercutting the program’s important statutory purposes.

The proposed rule, by effectively permitting increased discrimination, could also lead to lower success rates in the voucher program; that is, a lower share of families that receive vouchers in a given year would actually be able to use their voucher to sign a lease with a landlord.[25] Public housing agencies could also pay higher administrative costs: when a significant share of families that receive vouchers do not succeed in finding a place to rent with the voucher, agencies typically compensate by “overissuing” vouchers to eligible families. Issuing these vouchers to additional families requires more work on the part of agency staff — for instance, in notifying families that a voucher is available, verifying their income and eligibility, and briefing them on program rules and the housing search process. It could mean that available voucher resources in some cases go unused, not because local need for housing assistance has been met, but because of added inefficiencies that this rule would have created.

A long legacy of racist and discriminatory public policies played a central role in the creation and persistence of racially segregated neighborhoods.[26] For example, during the New Deal, Public Works Administration housing projects excluded Black families, and during that time many local governments blocked separate public housing projects intended for Black households. Once white families moved out of public housing after World War II with the creation of federally backed loan products to purchase homes (which also discriminated against Black families), Black families were allowed to move into public housing. But, due to white families using these new loan products and purchasing homes largely in the suburbs, this solidified and increased segregation. This enabled policymakers and institutions to actively make additional discriminatory decisions that diverted public or private investments and positive economic growth away from Black neighborhoods. Banks enacted redlining restrictions that discouraged investment in certain neighborhoods, usually those with a majority Black population. Federal, state, and local governments constructed highways, hazardous waste facilities, and other undesirable structures and facilities disproportionately in Black neighborhoods to avoid conflict with white neighborhoods.[27] Segregation also allows policymakers to overlook communities of color, resulting in underinvestment in critical institutions like schools and infrastructure like grocery stores, public green space, and transportation, which exacerbates neighborhood decline. This all has contributed to the situation mentioned above where nearly 80 percent of high-poverty, low-opportunity metropolitan neighborhoods are also “minority concentrated,”[28] as HUD defines these terms.

The Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program, designed to finance stable, affordable housing developments while minimizing segregation, is supposed to help break this trend, but discriminatory policies and practices can limit the program’s effectiveness. Disparate impact claims have long been used to stop these harmful practices. For example, disparate impact claims have been used to challenge zoning rules that limit multi-family buildings and perpetuate segregation because people of color in those communities disproportionately live in multi-family housing.[29] HUD’s proposed rule would undermine the LIHTC program’s purpose by making it substantially harder to stop LIHTC developments’ relegation to low-opportunity, “minority concentrated” neighborhoods. It would also make it less likely that states, localities, and developers will be held accountable for perpetuating segregation, which runs counter to the FHA-mandated obligation to affirmatively further fair housing.

People with disabilities have historically been segregated and isolated in institutions such as nursing homes or mental health facilities due to an inability to access housing and adequate community-based support services. This unnecessary segregation not only harms people’s well-being and basic liberties, but also increases government spending on health care services because these facilities are often significantly more expensive than housing and services in the community.[30]

Governments, landlords, and developers often make it difficult to create and access housing for this population. For example, a landlord requiring a tenant to work a certain number of hours a week discriminates against individuals who can afford the housing (perhaps because they receive rental assistance) but must work part time due their health conditions. Also, local zoning restrictions that prohibit new apartment buildings — which must meet modern accessibility standards in building codes — could reduce access to accessible housing that also is located near medical, transportation, or other services that people with disabilities need. Such policies and practices undermine the FHA. And, as the Supreme Court held in its landmark decision Olmstead v. L.C., the Americans with Disability Act requires states and localities to generally serve people with disabilities in the community rather than in institutions, when community-based services can appropriately meet their needs.[31]

As Table 1 shows, people with disabilities are slightly over-represented among low-income renters in the United States and are also more likely to receive rental assistance. Through the affirmatively furthering fair housing requirement, HUD has a legal obligation to both protect and advance ways to help people with disabilities, as a protected class, access affordable housing.[32] That obligation extends to both those who receive rental assistance and those who don’t. The Administration’s proposed rule would harm people with disabilities’ ability to bring forward cases against policies and practices that effectively discriminate against them, likely leading more landlords and communities to unnecessarily restrict housing options for people with disabilities.