Agencies Generally Use All Available Voucher Funding to Help Families Afford Housing

But Challenges in Some Communities Remain

End Notes

[1] For general information on the Housing Choice Voucher program, see “Policy Basics: The Housing Choice Voucher Program,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/policy-basics-the-housing-choice-voucher-program.

[2] Gale Holland and Abby Sewell, “Subsidized rent, but nowhere to go: Homeless vouchers go unused,” Los Angeles Times, May 30, 2016, http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-homeless-vouchers-snap-story.html. For another example, see Laura Sullivan and Meg Anderson, “Section 8 Vouchers Help The Poor — But Only If Housing Is Available,” a National Public Radio story about the experiences of several families in Dallas, May 10, 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/05/10/527660512/section-8-vouchers-help-the-poor-but-only-if-housing-is-available. Several reports also followed the publication of a new Urban Institute study of landlord behavior, cited below.

[3] Alison Bell, Barbara Sard, and Becky Koepnick, “Prohibiting Discrimination Against Renters Using Housing Vouchers Improves Results,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 20, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/prohibiting-discrimination-against-renters-using-housing-vouchers-improves-results.

[4] “Three Out of Four Low-Income At-Risk Renters Do Not Receive Federal Rental Assistance,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, https://www.cbpp.org/three-out-of-four-low-income-at-risk-renters-do-not-receive-federal-rental-assistance.

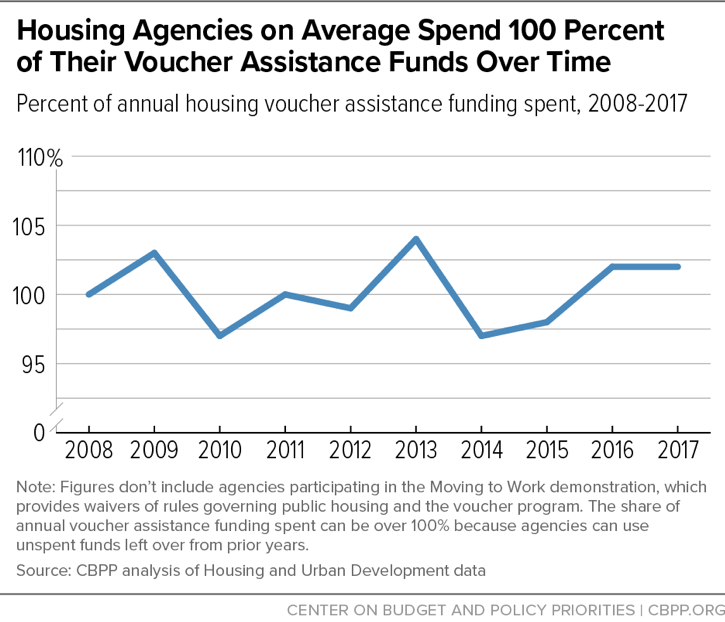

[5] For a more detailed explanation of this and other terms involved with housing vouchers, see Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Housing Voucher Success and Utilization Indicators, and Understanding Utilization Data,” https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/housing-voucher-success-and-utilization-indicators-and-understanding-utilization.

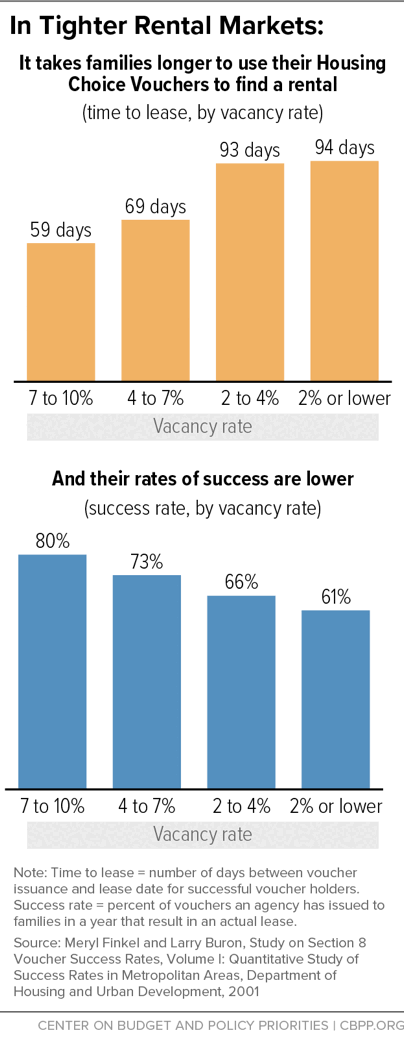

[6] Meryl Finkel and Larry Buron, “Study on Section 8 Voucher Success Rates, Volume I, Quantitative Study of Success Rates in Metropolitan Areas,” Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2001, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/pubasst/sec8success.html. Success rates in metro areas studied varied from 37 to 100 percent.

[7] This figure is the average for 2008 to 2017 for all of the more than 2,000 state and local agencies that administer housing vouchers, except for the 39 agencies that participate in the Moving to Work (MTW) demonstration. Data include all Housing Choice Voucher assistance funding received in each year, including funding for new tenant protection, Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (VASH), and other new vouchers awarded to agencies during the year, and total voucher housing assistance payments (HAP). In some years, some agencies spend more than 100 percent of their funding allocations by using unspent funds left over from prior years.

Voucher funds expenditure rates among MTW agencies are historically much lower, on average, than among other agencies. The average expenditure rate among non-MTW agencies was 102 percent in 2016 and 2017, but just 88 percent among MTW agencies, for example, and MTW agencies received $775 million in voucher assistance funds over the two-year period that they either did not spend or spent on other activities, such as program administration, resident services, or housing rehabilitation or development. (MTW agencies are allowed to receive waivers of many program rules, including the rules that funding be spent on housing vouchers.) As a result, MTW agencies provide housing assistance to tens of thousands fewer families than they could with the funds they received. For further discussion, see Will Fischer, “New Report Reinforces Concerns About HUD’s Moving to Work Demonstration,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 30, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/new-report-reinforces-concerns-about-huds-moving-to-work-demonstration.

[8] In 2016 and 2017, for example, California housing agencies spent 101 percent of the voucher assistance funds they received, compared to about 102 percent nationally. These figures do not include data for the 39 agencies (seven of which are in California) participating in the Moving to Work demonstration.

[9] An important factor contributing to the very high voucher funds expenditure rate is the fact that most families using vouchers received their vouchers in prior years and continue to rent from the same landlord. Low success rates affect only families that have just received a voucher. In addition, HUD is authorized to reduce renewal funding allocations at agencies that build up excess reserves of unspent funds, effectively forcing agencies to spend these reserves to renew assistance and improving the program’s funds expenditure rate.

[10] These figures do not include agencies participating in the MTW demonstration. Nearly 1,300 non-MTW agencies spent more than 100 percent of the funds they received in 2017 by spending down reserves of unspent funds left over from prior years. Agencies were forced to rely on funding reserves because the renewal funding that Congress provided under the fiscal year 2017 appropriations law was 3 percent less than agencies required according to the formula that HUD uses, which calculates renewal funding eligibility based on actual voucher usage and costs in the prior year, adjusted for inflation and other factors.

[11] For instance, rental vacancy rates in the Minneapolis-St. Paul and Denver metro areas have hovered around 4 to 5 percent in recent years, according to Census surveys, which is similar to the rate in the New York City metro area, https://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/data/ann17ind.html.

[12] Finkel and Buron, op. cit.

[13] Linda Pistilli, Study on Section 8 Voucher Success Rates Volume II: Qualitative Study of Five Rural Areas, Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2001, https://www.huduser.gov/portal//Publications/pdf/sec8_vol2.pdf.

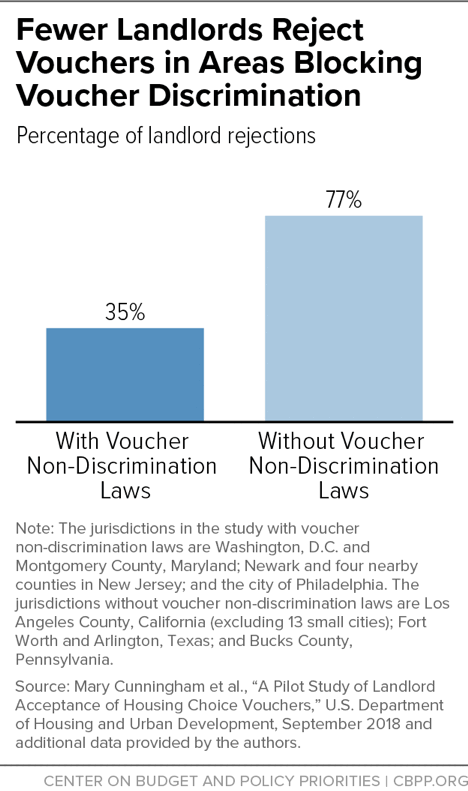

[14] There is evidence that some owners refuse to rent to voucher holders as a pretext for discriminating against groups of people that are protected under the Fair Housing Act. Owners of housing developed with Low Income Housing Tax Credits or other federal subsidies may not discriminate against voucher holders, even if no local law prohibits such discrimination.

[15] Mary K Cunningham et al., “A Pilot Study of Landlord Acceptance of Housing Choice Vouchers,” Urban Institute, August 20, 2018, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/pilot-study-landlord-acceptance-housing-choice-vouchers.

[16] Bell et al., op. cit.

[17] More comprehensive and detailed discussions of these and other strategies are available in: Finkel and Buron, op. cit.; Meryl Finkel et al., “Costs and Utilization in the Housing Choice Voucher Program,” Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2003, https://www.huduser.gov/portal//Publications/PDF/utilization.pdf; “Dialogue with Amy Ginger, HUD Director of Housing Voucher Program, on How to Improve Housing Voucher Utilization,” April 6, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/3-4-19hous-interview.pdf; and the guidance on improving success rates and utilization that HUD provides at https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/programs/hcv/Tools. For a discussion of strategies to help families to locate in low-poverty areas with quality schools and other opportunities, see Barbara Sard et al., “Federal Policy Changes Can Help More Families with Housing Vouchers Live in Higher-Opportunity Areas,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 4, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/federal-policy-changes-can-help-more-families-with-housing-vouchers-live-in-higher.

[18] In general, housing agencies can use admissions preferences to attract tenants who are most likely to benefit from relevant services that partner organizations provide, and thereby bring partner organizations to the table. In this way, agencies can leverage support services for tenants through their use of admissions preferences. See Jeffrey M. Lubell, Kathryn P. Nelson, and Barbara Sard, “How Housing Programs’ Admissions Policies Can Contribute to Welfare Reform,” in A Place to Live, a Means to Work, Fannie Mae Foundation, 2003.

[19] Philip Garboden et al., “Urban Landlords and the Housing Choice Voucher Program: A Research Report,” Department of Housing and Urban Development, May 2018, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/UrbanLandlords.html.

[20] Voucher payment standards, which vary by unit bedroom number, are the maximum rent that a voucher subsidy will cover. If families choose units that rent above the payment standard, then they must pay the difference, in addition to the 30 percent of adjusted household income that they typically pay already. Housing agencies have discretion to set payment standards at 90 to 110 percent of the Fair Market Rent (FMR), although they can ask HUD to set them above 110 percent of FMR. They may also use Small Area Fair Market Rents (SAFMRs) in higher-rent zip codes, or use SAFMRs in every zip code with HUD’s permission. (A small number of agencies are required to use SAFMRs in every zip code.) See “A Guide to Small Area Fair Market Rents (SAFMRs): How State and Local Housing Agencies Can Expand Opportunity for Families in All Metro Areas,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 4, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/a-guide-to-small-area-fair-market-rents-safmrs.

[21] See “Policy Basics: Project-Based Vouchers,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/policy-basics-project-based-vouchers. Regarding housing for people with special needs, see Ehren Dohler et al., “Supportive Housing Helps Vulnerable People Live and Thrive in the Community,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 31, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/supportive-housing-helps-vulnerable-people-live-and-thrive-in-the-community.

[22] As noted above, see “Housing Voucher Success and Utilization Indicators, and Understanding Utilization Data” for further detail on terms.

[23] See, for example, the 2018 Notice of Funding Availability for new mainstream vouchers, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/SPM/documents/FY17%20Mainstream%20Voucher%20Program%20NOFA.pdf.

[24] See Ginger interview, op cit.

[25] HUD tracks voucher and voucher funds utilization as part of SEMAP. In recent years, HUD has regularly reviewed these data to identify agencies that are underutilizing funds, and offered them technical assistance aimed primarily at improving funds management, such as helping them track the expenditures of assistance funds and remaining balances of available funds more accurately, and adjusting voucher issuances to use available funds more efficiently to assist families. Regarding the new HUD task force, see “HUD Launches Campaign to Boost Landlord Acceptance of Housing Vouchers,” Department of Housing and Urban Development press release, August 20, 2018, https://www.hud.gov/press/press_releases_media_advisories/HUD_No_18_086.

[26] States and localities should also do more, particularly in regions where markets are tight or success rates tend to be low for other reasons. More states should enact laws prohibiting discrimination against households using vouchers, for example. Currently, only 34 percent of households with housing vouchers live in jurisdictions with protections against discrimination by landlords, despite the growing body of evidence indicating that such laws substantially increase the program’s effectiveness. See Bell et al., op. cit. Learning from examples in Illinois and Virginia, states and localities can also offer targeted tax or other incentives to landlords to accept housing vouchers — for instance, incentives targeted to landlords in high-opportunity areas where vouchers may be harder to use. Mary K. Cunningham, “To increase housing choice, try incentivizing landlords,” Urban Institute, September 15, 2016, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/increase-housing-choice-try-incentivizing-landlords.