State and local housing agencies have important new tools to help families with housing vouchers move to high-opportunity neighborhoods with low crime and strong schools, which tend to have higher rents. A November 2016 Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) rule expands use of Small Area Fair Market Rents (SAFMRs), which set voucher amounts at the neighborhood rather than metro level — letting vouchers pay more in high-rent neighborhoods and less in low-rent neighborhoods. Under the new policy:

SAFMRs can expand opportunity for low-income families with Housing Choice Vouchers, but their effectiveness will depend on steps that voucher program administrators and others take at the local level. This guide provides background on SAFMRs and information on how agencies can implement them. It answers these questions:

Housing voucher subsidies are capped based on fair market rents (FMRs) that HUD estimates each year for modest housing units in a geographic area. A family with a voucher pays about 30 percent of its income for rent and utilities, and the voucher covers the remainder up to a payment standard set by the state or local housing agency. The payment standard generally must be within 10 percent of the FMR, although agencies may set higher or lower standards if they meet certain criteria and get HUD approval.[1] Families may rent reasonably priced units above the payment standard, but they must pay the extra rent themselves, on top of the 30 percent of their income they would otherwise pay.[2]

Historically, HUD has established a single set of FMRs for units of various sizes in each metro area or rural county. In recent years, however, HUD has tested SAFMRs, which are based on rents in particular zip codes and therefore reflect neighborhood rents more accurately than metro-level FMRs. SAFMRs were first used in the Dallas area in fiscal year 2011 following settlement of a lawsuit claiming that metro-wide FMRs prevented minority voucher holders from moving to predominantly white neighborhoods with higher rents. Two years later, HUD initiated an SAFMR demonstration allowing five agencies in other parts of the country to test the approach. After early results suggested that SAFMRs were effective at helping voucher holders in these areas move to higher-opportunity neighborhoods without undue administrative burdens, HUD issued the 2016 expansion regulation with the goal of providing similar opportunities to families in other parts of the country.

SAFMRs have two main benefits:

- they can provide voucher holders greater access to high-opportunity areas; and

- they can make the voucher program more cost-effective.

Both of these benefits stem from having payment standards that more accurately reflect neighborhood rents. Payment standards based on the broader metro-level FMRs are often too low to cover rents in some neighborhoods and higher than needed in others. When the payment standard is too low — as is often the case in neighborhoods with low poverty, low crime, and high-performing schools — families will struggle to find units they can rent with their voucher. When the payment standard is too high, families can afford units that are larger or have more amenities than they need, and owners can potentially charge above-market rents (unless housing agencies strictly enforce rules requiring that rents be reasonable in the local market). Such excessive payments reduce the voucher program’s cost-effectiveness and encourage families to use vouchers — and owners to accept them — in lower-rent, higher-poverty neighborhoods.

Research shows that SAFMRs have worked well at helping families move to higher-opportunity neighborhoods. In August 2017, HUD released an interim evaluation of SAFMR implementation at two Dallas-area agencies and the five SAFMR demonstration agencies. During the period SAFMRs were used, the share of voucher holders who lived in high-opportunity neighborhoods rose at SAFMR agencies but not at a group of comparison agencies that didn’t use SAFMRs. (Researchers identified high-opportunity neighborhoods through an index that considered poverty rate, school quality, access to jobs, and exposure to environmental toxins.)[3] Earlier research also found that SAFMRs in Dallas enabled voucher holders to move to neighborhoods with less crime.[4] These findings have important implications for families’ well-being, since research shows moving to lower-poverty neighborhoods can lead to major improvements in adults’ health and children’s long-run earnings and chances of attending college.[5]

SAFMRs have also made the voucher program more cost-effective. The interim evaluation found that average subsidy costs fell 13 percent at SAFMR agencies from 2010 to 2015, because the total subsidy reductions from using SAFMRs in low-rent neighborhoods exceeded increases in high-rent neighborhoods. Costs also fell at comparison agencies (partly because budget cuts during this period caused many agencies to lower subsidy levels), but by less than half as much. The effects of SAFMRs on costs at individual agencies will depend on a range of factors, including how SAFMRs compare to metro FMRs in their jurisdiction, what kinds of tenant protections the agency adopts, and how many families move to higher-rent areas. To the extent that SAFMRs reduce per-voucher costs, they can enable agencies to provide vouchers to more families with their limited funds. (One risk is that savings could come at the expense of increasing rents for families already using vouchers in low-rent neighborhoods, but as discussed below, HUD’s rule gives agencies strong tools to protect those families.)[6]

In addition to helping low-income families access higher-opportunity neighborhoods and potentially extending assistance to more families, SAFMRs can also benefit housing agencies in other ways. SAFMRs can help an agency boost its performance under the Section Eight Management Assessment Program (SEMAP) by making it easier to earn “deconcentration bonus” points for enabling voucher holders to move to low-poverty neighborhoods,[7] meet its obligation to affirmatively further fair housing by providing families access to more racially integrated neighborhoods, and help avoid excessive concentration of voucher holders in a small number of neighborhoods (which in some cases may reduce community support for the agency and the voucher program).

Agencies may experience higher administrative costs to implement SAFMRs for items such as modifying automated systems, training agency staff, and setting payment standards. But the results from the interim evaluation suggest that these costs were modest and consisted mainly of one-time or transitional expenses, and HUD has indicated that it may provide added administrative funding to cover at least some such costs.[8] Moreover, SAFMRs may enable agencies serving jurisdictions with high rents relative to their metropolitan area to raise the share of voucher recipients who successfully lease housing, which could lower their administrative costs by reducing the rate at which they must reissue returned vouchers.

HUD Exchange’s SAFMR page includes:

HUD issued a final regulation on November 16, 2016 expanding use of SAFMRs.[9] The regulation requires agencies in certain metro areas to use SAFMRs and allows agencies in the remaining metro areas to use SAFMRs voluntarily. (HUD does not publish SAFMRs for non-metropolitan areas, so agencies there will continue to use county FMRs.) On January 17, 2018, HUD published guidance on how agencies can implement the regulation.[10] HUD has also made available other materials to support SAFMR implementation (see box), including an implementation guidebook, answers to frequently asked questions, case studies of SAFMR implementation at two local agencies, and sample documents that agencies can use in implementing SAFMRs.[11]

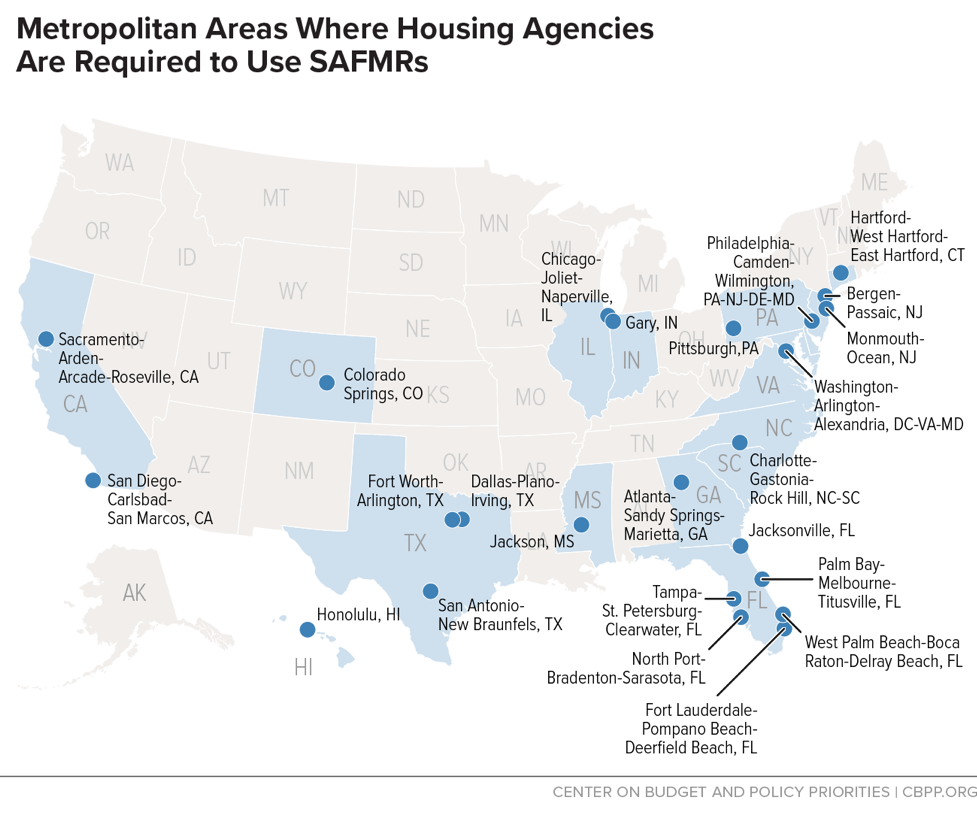

The 2016 rule required housing agencies to use SAFMRs for their tenant-based vouchers in 24 metro areas (see map below) — including the Dallas area, where SAFMRs have been required since 2011. These SAFMR designations became effective on October 1, 2017, and agencies in the 23 new SAFMR areas were to be required to begin using SAFMR-based payment standards by January 1, 2018.

In practice, implementation was delayed for three months by a failed HUD effort to suspend mandatory SAFMRs for two years.[12] On December 23, 2017 a federal judge ruled that HUD’s delay was unlawful. HUD’s new guidance states that agencies will now be expected to complete implementation by adopting SAFMR-based payment standards — that is, payment standards that fall between 90 and 110 percent of the SAFMR in all of the zip codes they serve — no later than April 1, 2018.

The new payment standards will then apply immediately to voucher holders who are new to the program or move to a new unit. For voucher holders who remain in place, payment standard increases will apply at the family’s next annual review and reductions will apply no sooner than the second annual review (and as discussed below, agencies have broad flexibility to delay this further).[13] Agencies in mandatory SAFMR areas do not need to amend their voucher administrative plans to adopt SAFMR-based payment standards (although, as discussed below, some policies related to SAFMRs but not required for initial adoption must be documented in the administrative plan).[14]

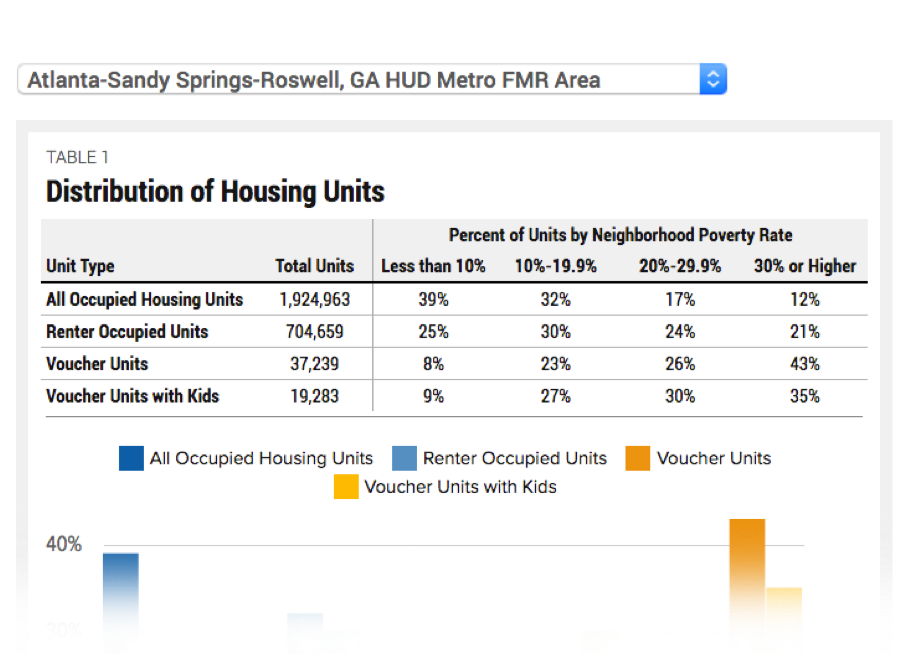

HUD selected these 24 metro areas because they met criteria designed to identify areas where SAFMRs would be most effective: (1) vouchers were disproportionately concentrated in low-income neighborhoods; (2) many of the area’s rental units were in zip codes with SAFMRs above 110 percent of the metro FMR; (3) the rental vacancy rate exceeded 4 percent; and (4) at least 2,500 vouchers were in use in the metro area. (See text box: “SAFMR Requirements Target Areas That Need Them.”) Mandatory SAFMR designations will remain in place indefinitely, although HUD can suspend them for a particular area or agency due to a natural disaster or other unusual circumstance. HUD may add new mandatory SAFMR areas every five years.

See interactive showing that in metro areas where SAFMRs are required, voucher holders are likelier than other renters to live in high-poverty, high-minority neighborhoods.a

a Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Housing Voucher Policy Designed to Expand Opportunity Targets Areas that Need It,” January 9, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/housing-voucher-policy-designed-to-expand-opportunity-targets-areas-that-need-it.

HUD has taken the position that agencies participating in the Moving to Work (MTW) demonstration that operate in a mandatory SAFMR area may exercise their flexibility under MTW to establish an “alternative payment standard policy” rather than implementing SAFMRs, if that policy appears in an MTW plan approved by HUD.[15] MTW agencies are subject to the Fair Housing Act, however, so they must ensure that any alternative policy is as effective as SAFMRs in providing opportunities to racial and ethnic minorities and other protected groups to live in communities of their choice, including in areas where their racial or ethnic group does not predominate. In the absence of an approved alternative policy, MTW agencies are subject to the same requirements to implement SAFMRs as other agencies.

HUD’s rule also allows agencies to use SAFMRs voluntarily if they are located in a metro area where SAFMRs are not required. Agencies can do this in two ways.

-

Agencies may set payment standards up to 110 percent of the SAFMR in particular zip codes even if this is above 110 percent of the metro-area FMR, without the HUD approval normally required for exception payment standards. This offers substantial new flexibility, since in high-cost zip codes 110 percent of the SAFMR can be as much as several hundred dollars above 110 percent of the metro FMR. An agency could take this step for any combination of zip codes in its service area, but the higher payment standards must always cover the full area of each zip code.[16] (Agencies using this option must still seek HUD approval and meet certain criteria to set payment standards below 90 percent of the metro FMR in low-rent zip codes.)

The higher payment standards set under this option are considered “exception payment standards.” But unlike most types of exception payment standards they do not require HUD approval, they do not require agencies to submit data justifying the increase, and they are exempt from a cap that limits other exception payment standards to areas with no more than half of a metro area’s population. To exercise this option, an agency need only send an email to [email protected] notifying HUD that it has adopted an SAFMR-based exception payment standard.[17]

- Agencies can request approval from HUD to adopt SAFMRs in place of metro FMRs. The request must state that the agency has completed a four-part comparison of SAFMRs to metro FMRs described in HUD’s guidance notice, and should also be sent to [email protected].[18] If HUD approves the request, the agency must revise its administrative plan to state that it will operate using SAFMRs.

The first option is simpler and generally more flexible, since it requires no action beyond what would be needed for any other payment standard change (except a brief notification email to HUD) and allows an agency to choose whether to adopt SAFMR-based payment standards in all of the zip codes it serves or only in some. By contrast, the second option would require the agency to seek HUD approval, revise its administrative plan, and use SAFMR-based payment standards throughout its service area. The second option, however, is more flexible in three respects: it would allow the agency to set different SAFMR-based payment standards for different parts of a zip code, to apply SAFMRs to tenant-based vouchers but not project-based vouchers, and to set SAFMR-based payment standards below 90 percent of the metro FMR without meeting certain criteria and seeking special HUD approval.

Neither option would compel other agencies in the metro area to use SAFMR-based payment standards (even when the jurisdictions of two or more agencies overlap). Families that receive vouchers from agencies using SAFMRs may have difficulty renting in high-opportunity neighborhoods in the jurisdictions of agencies that continue to use metro FMRs, since when a family moves outside the jurisdiction of the agency that issued its voucher, the agency in the destination community then administers the voucher using its own payment standards under the voucher program’s “portability” rules. Agencies could seek to avoid this outcome by encouraging other agencies in the area to also adopt SAFMR-based payment standards, or by entering regional partnerships or consortia to coordinate aspects of voucher program administration. In addition, housing agencies in some states are permitted to directly administer vouchers beyond their regular service areas. HUD’s November 2016 rule permits such agencies to use either of the two options described above to set SAFMR-based payment standards for any metropolitan zip code where they are administering vouchers.

A series of implementation decisions will influence how effective SAFMRs are in expanding opportunity and avoiding hardship for voucher holders.

Setting Payment Standards

Agencies using SAFMRs in place of metro FMRs may set payment standards anywhere from 90 to 110 percent of the SAFMR in each zip code, just as other agencies can with metro- or county-level FMRs. HUD plans to issue a notice establishing procedures for requesting exception payment standards above 110 percent of the SAFMR, which would give agencies greater flexibility to raise payment standards.[19] In addition, agencies using SAFMRs in place of metro FMRs can set payment standards up to 120 percent of the SAFMR for individual families that include a person with a disability, if needed to enable the family to rent suitable housing (just as other agencies can set payment standards up to 120 percent of the metro FMR for this purpose).

- The simplest option will be for agencies to establish payment standards at 100 percent of the SAFMR in each zip code, which allows the agency to simply adopt the published SAFMR schedule as its payment standard schedule. SAFMRs are designed to be adequate to cover housing costs for 40 percent of recently rented, standard-quality units in each zip code, so in many areas payment standards at the SAFMR will give voucher holders a reasonable range of rental options. Several local agencies that have tested SAFMRs have taken this approach, such as the Plano (Texas) Housing Authority, which set payment standards at the SAFMR throughout the period covered by the interim evaluation. One advantage of this was that Plano avoided any administrative costs from determining payment standards for each zip code, which HUD’s interim SAFMR evaluation found was one of the main drivers of added administrative costs at some agencies.

Agencies that adopt SAFMR-based exception payment standards only for selected zip codes would have many of the same choices, including whether to group high-rent zip codes into larger payment standard zones. These agencies must, however, always apply SAFMR-based exception payment standards to the full area of each zip code. In addition, agencies using SAFMR-based exception payment standards may wish to consider lowering or freezing payment standards in neighborhoods where the current, metro-FMR-based payment standard is above typical market rents, to reduce the risk of overpaying landlords and offset any added costs from higher payment standards in high-rent neighborhoods.

All agencies should continuously monitor outcomes such as rent burdens, success rates, total housing assistance payment expenditures, and the share of voucher holders renting in high-opportunity areas to determine if adjustments to payment standards or other policies are needed. Agencies are permitted to adjust payment standards at any time.

SAFMRs will expand opportunity more effectively if they are accompanied by other steps to help families rent in low-poverty neighborhoods that the higher payment standards make potentially accessible. For example:

Some of these actions (such as revising agency policies) would carry little or no cost, while the others could be funded through voucher administrative fees (including fee reserves), other federal grants such as HOME and Community Development Block Grants (CDBG), or contributions from philanthropies or local governments.[22]

Lower payment standards in low-rent neighborhoods can raise rent burdens for voucher holders there, but HUD’s November 2016 rule includes new measures that limit increases in rent burdens and give housing agencies the ability to prevent them entirely for voucher holders who remain in place.

First, HUD adopted a policy limiting FMR declines to no more than 10 percent per year. In the 23 new mandatory SAFMR metro areas, this means the 2018 SAFMRs are no lower than 90 percent of the 2017 metro FMR, and in each future year the SAFMR will be no lower than 90 percent of the previous year’s SAFMR. In the lowest-rent neighborhoods, SAFMRs will therefore phase down gradually rather than dropping abruptly.[23]

Second, agencies may choose to delay the impact of lower payment standards on families that continue to use a voucher in the same unit. The new HUD rule allows agencies to adopt any of four policies to apply payment standard reductions to families in place at the time the payment standard becomes effective:

- Maintain the regular practice of applying reductions at the second annual review, which gives families one to two years of notice before the new payment standard goes into effect;

- Phase the payment standard reduction in gradually, for example by applying a 15 percent payment standard reduction in three increments of 5 percent per year (with the first part of the reduction going into effect no sooner than the second annual review);

- Permanently hold families harmless by continuing to use the previous, higher payment standard for as long as a family remains in the same unit;

- Applying a portion of the reduction and then holding families harmless after that, for example by applying only 5 percentage points of a 15 percent reduction (again no sooner than the second annual review).[24]

Agencies can adopt different policies for different portions of their service areas. For example, an agency could apply reductions at the second annual review in most zip codes but institute a permanent hold-harmless in neighborhoods where market rents are rising rapidly and are expected to soon surpass the SAFMR. Agencies must, however, use the same policy for all households in a particular geographic area. For example, they are not permitted to adopt a hold-harmless for all elderly and disabled households in a specified zip code, but not for other households in the same zip code.[25] (As noted above, however, they may provide exception payment standards up to 120 percent of the SAFMR when needed to enable people with disabilities to rent suitable housing — including in cases where families need such exceptions to remain in their current homes.)

Agencies must include in their administrative plans the particular policies they plan to follow to implement reduced payment standards (but they are permitted to make the needed administrative plan changes after the payment standard changes have become effective).[26] In addition, they are required to notify voucher holders whose current payment standard is set to decline at least 12 months before they will be affected, so they can plan ahead and potentially move.

Housing agencies are permitted to “project-base” some of their vouchers — that is, to enter into long-term agreements with owners requiring that the vouchers be used in specified developments. Applying SAFMRs to project-based vouchers could have important benefits, including making it easier to place project-based vouchers in high-opportunity neighborhoods.

Under HUD’s rule, when an agency uses SAFMRs in place of the metro FMR, project-based vouchers are not automatically subject to SAFMRs. (By contrast, when agencies adopt SAFMR-based exception payment standards for particular zip codes, those apply to project-based vouchers in the same way that other voucher payment standards do.) The rule gives agencies the option to apply SAFMRs to new project-based voucher developments. To do this, the agency must adopt a policy applying SAFMRs to all project-based voucher developments where the notice of owner selection is issued after the policy’s adoption and incorporation in the administration plan. Agencies may also apply SAFMRs to existing project-based voucher developments with the owner’s agreement, but agencies are under no obligation to do so. Even if an agency applies SAFMRs to all new project-based voucher developments going forward, it could continue to use metro FMRs for some or all existing developments.

As noted, SAFMR implementation on the whole has been accompanied by lower per-voucher costs. As a result, agencies implementing SAFMRs should usually be able to serve as many or more families as they would have without SAFMRs. However, some agencies may face higher per-voucher costs, based on the choices they make, and agencies should assess the likely impact of SAFMRs on per-voucher costs based on their individual circumstances. Of course, where needed, higher per-voucher costs are not necessarily a bad thing — especially if they expand family access to higher-opportunity areas (and promote fair housing goals), or protect tenants on fixed incomes who need to stay in lower-rent neighborhoods.

Agencies could see per-voucher costs rise if they use the flexibility described above to sharply limit the impact of payment standard declines, or if they choose to adopt SAFMR-based exception payment standards in high-rent neighborhoods but do not reduce payment standards in low-rent neighborhoods. In addition, agencies whose service areas consist mainly of high-rent zip codes could experience significant average per-voucher cost increases due to SAFMRs (which would also likely reduce rent burdens for many of the families they assist). HUD has authority to provide added voucher renewal funding to agencies that serve high-cost jurisdictions in mandatory SAFMR areas, but has not indicated whether it will do so.

HUD’s SAFMR rule gives housing agencies major new tools that can substantially alter how the voucher program operates in communities around the country. Research shows that those changes can deliver major benefits for low-income families and children.[27] Whether those benefits are realized, however, will depend on the actions agencies and others take to implement the new tools and help families make the most of the opportunities they offer.