The Trump Administration has issued guidance inviting states to seek demonstration projects — often called waivers — that would radically overhaul Medicaid coverage.[1] Under the guidance, states could apply for waivers that would convert their Medicaid programs for many adults into a form of block grant, with capped federal funding and new authorities to cut coverage and benefits.

The proposed waivers are a lose-lose proposition for people with Medicaid and for states. Far from promoting better health outcomes, as the Administration has claimed, the waivers would worsen people’s health by taking away coverage and reducing access to care. For states, they would mean greater financial risk, with federal funding cuts most likely to occur during recessions, public health emergencies, and other times when states face high demand for coverage and strain on other parts of their budgets. States taking up the proposed waivers should also expect to face litigation, since the waivers appear to violate federal law in several respects.

The Administration has long sought to enact legislation that would undermine or eliminate the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults and impose funding caps on the rest of the Medicaid program. The guidance is the latest in a series of administrative actions aiming to advance those same goals.[2]

This paper answers various frequently asked questions about the new guidance:

States could seek block grant waivers for adults under age 65, other than those they are required to cover under federal law. In practice, this means the waivers could apply to the more than 17 million parents and other adults currently covered through the ACA Medicaid expansion, additional adults states choose to cover through expansion in the future, and other groups states can choose but are not required to cover, such as pregnant women with incomes above the statutory minimums, adults receiving coverage only for family planning services, and certain low-income parents not covered through expansion. (We refer to these groups throughout as “adults subject to the guidance.”) The waivers would not apply to people who qualify for Medicaid because they receive federal disability assistance or need long-term services and supports, or to low-income pregnant women and parents states are required to cover.[3]

The Administration has claimed that the waivers would not affect people with disabilities, children, or other particularly vulnerable groups. In fact, states could seek waivers for:

- People with disabilities. Some 5 million people with serious physical disabilities or mental health conditions do not receive federal disability assistance or qualify for long-term services and supports, which means they would be subject to the guidance.[4] Most of these people have coverage through the ACA Medicaid expansion.

- People with chronic conditions or serious health needs. A study of adults enrolled in Michigan’s Medicaid expansion found that more than two-thirds had a chronic condition requiring regular treatment such as diabetes, hypertension, or depression.[5] The guidance does not exclude such individuals, nor does it exclude people with cancer or other acute health needs.

- Older adults. While Medicare-eligible seniors would be excluded, millions of older adults — including early retirees receiving Social Security but not yet eligible for Medicare — are covered through expansion.

- Low-income parents. When parents lose coverage, children are harmed as well, since they are more likely to be uninsured and less likely to get the care they need. Children also suffer when their parents cannot get needed care or their family’s financial security deteriorates.[6]

What cuts to coverage and benefits would the waivers allow? How would these cuts affect people with Medicaid?

The guidance offers states a slew of authorities to cut coverage and benefits for people with Medicaid. Some of these are unprecedented authorities never previously granted through waivers; others have been allowed previously (in some cases only by the current Administration) but would now be available on a fast-track basis for states seeking block grant waivers. States could choose which of these authorities to request in their waiver applications.

The guidance would allow states to:

- Take coverage away from people who don’t pay premiums, even those with very low incomes. Extensive research has shown that premiums significantly reduce low-income people’s participation in health coverage.[7] Nonetheless, the Trump Administration approved an unprecedented waiver in Wisconsin that allows the state to take coverage away from people with incomes as low as about 50 percent of the poverty line (about $500 per month in 2020) if they don’t pay premiums. Now, the guidance proposes to let states take coverage away from people at all income levels if they don’t pay premiums.

- Take coverage away from people who don’t report enough hours of work each month. In Arkansas, almost 1 in 4 people subject to this policy lost coverage, many of them people who were working or should have qualified for exemptions but were tripped up by red tape. In New Hampshire, about 40 percent of people subject to work requirements would have lost coverage had the state not put the policy on hold.[8]

- End retroactive coverage. Retroactive coverage is a longstanding Medicaid policy that requires Medicaid to cover enrollees’ medical costs for three months prior to enrollment (provided they were eligible for Medicaid during that period). Eliminating retroactive coverage means people who are eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled could face bankruptcy if they are unexpectedly ill or injured, and hospitals and other providers could incur large uncompensated care bills for people eligible for coverage under federal law.

- Delay coverage for new enrollees. In states that provide Medicaid coverage through private managed care plans, it can take a month or more for enrollees to select a plan and enroll once they are determined eligible. But states are required to provide people with health coverage in the interim (generally through their fee-for-service Medicaid programs).[9] On top of eliminating retroactive coverage, the guidance would let states keep eligible people uninsured until they are enrolled in a managed care plan. For those who are sick and need treatment when they apply for coverage, that could mean delaying needed care, incurring medical debt, and/or imposing additional large uncompensated care bills on hospitals and physicians.

States could also:

- Deny coverage for prescription drugs, likely leading to denials of expensive but needed treatments. The guidance gives states the unprecedented authority to deny coverage for certain FDA-approved prescription drugs, an approach known as a “closed formulary.”[10] While states would be required to have an exceptions process for people who need drugs that aren’t included in the formulary, states that obtain closed formulary authority would likely make it extremely difficult for people to access expensive but high-value drugs. The guidance requires states to continue covering all drugs in certain categories, but it leaves most categories out, including treatments for cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, and cancer.

- Impose higher copayments than Medicaid law allows, including for physician visits and prescription drugs. “Even relatively small levels of [Medicaid] cost sharing in the range of $1 to $5 are associated with reduced use of care, including necessary services,” a Kaiser Family Foundation literature review concluded.[11] For example, research shows that copays for prescription drugs deter people from getting needed, high-value care, with several studies finding that modest increases in prescription drug copays increase hospitalizations by discouraging people from taking needed drugs.[12]

- Waive standards and oversight of managed care plans. Without federal standards and oversight, states could seek to save money by allowing plans to offer such narrow networks that Medicaid enrollees would lack access to certain specialists or by letting plans use tools like overly stringent prior authorization requirements to regularly deny needed care.

- Eliminate coverage for non-emergency medical transportation. This benefit is crucial to obtaining care for people without access to cars or public transportation, for example, people in rural areas whose health conditions leave them unable to drive. People most frequently rely on non-emergency medical transportation to attend medical appointments for behavioral health services, dialysis, and preventive services.[13]

- Providing less comprehensive coverage to 19- and 20-year-olds. Under current policy, these young adults are entitled to the same comprehensive Medicaid benefits package as children. That means, for example, that they are guaranteed dental and vision coverage, and states cannot limit the number of behavioral health or other appointments they have in a month. Under the guidance, states could impose these restrictions, which would have particularly harmful impacts on young adults with complex health needs.

States that seek waivers only for low-income adults for whom they are not receiving the ACA’s enhanced federal matching rate for full Medicaid expansion would be allowed to introduce even more restrictions.[14] The guidance suggests they could cap enrollment, meaning that they could deny coverage to people who meet income and other eligibility criteria once the cap was reached. The guidance would also allow them to reintroduce asset tests for Medicaid coverage, a policy the ACA eliminated for most adults because evidence showed almost no low-income adults had substantial assets and because the need to document assets was a major barrier to coverage.

States adopting block grant waivers would put themselves at risk for substantial federal funding cuts.

Currently, federal Medicaid funding adjusts to meet need. If more people sign up for Medicaid when a recession hits, or if per-person costs increase during a public health emergency — such as the opioid epidemic or an infectious disease outbreak like the new coronavirus — federal funding automatically increases to cover most of the extra costs. For adults covered through the ACA Medicaid expansion, the federal government covers 90 percent of all costs.

In contrast, states adopting block grant waivers would be required to accept caps on their federal funding, with states responsible for 100 percent of costs above the caps.

The guidance allows states to choose either a per-person or an aggregate cap, although it encourages the latter. Under a per-person cap, a state’s federal funding would be limited to the cap amount multiplied by the number of people enrolled. Under an aggregate cap, a state’s federal funding would be limited to the cap amount, with no adjustments for changes in enrollment.

The guidance proposes to set initial caps based on states’ past spending levels and to increase the caps each year based on either the projected growth in the medical care component of the consumer price index (CPI-M) or the actual average increase in per-capita costs for the relevant group of enrollees over the last five years — whichever is lower.[15] Per-person caps would grow at that rate; aggregate caps would grow at that rate plus one-half of a percentage point.

These growth rates make it highly likely that states will frequently hit the caps unless they make significant cuts to their programs to stay below them. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that per-enrollee costs for adults subject to the guidance will grow considerably faster than the CPI-M. [16] The one-half of one percentage point adjustment to the aggregate caps to compensate for enrollment growth is likely also inadequate, since the non-elderly population grows by almost 1 percent per year.[17]

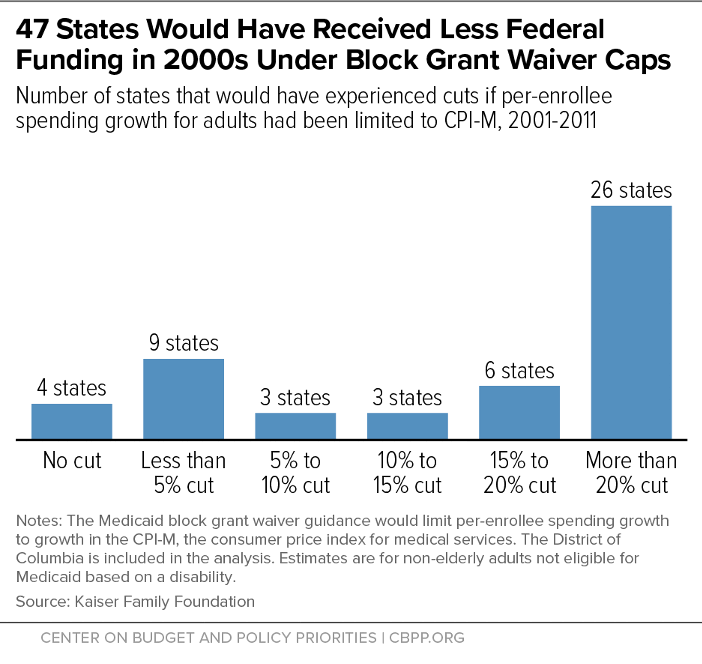

And the CBO projections of average, nationwide growth rates mask substantial variation. First, nationwide growth rates in particular years will likely substantially exceed the average if there is a recession or serious public health emergency. Second, state growth rates vary widely relative to the national average. For example, from 2000-2011, average annual growth in per-enrollee costs for the relevant group of adult enrollees ranged from about 0 to about 12 percent across states.[18]

Nearly all states would have experienced at least some decline in federal funding from 2000-2011 if growth in per-enrollee funding for the relevant group of adults had been capped at the CPI-M, a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis found, with 26 states experiencing cuts of more than 20 percent.[19] (See Figure 1.) While Medicaid expansion has changed the population of adults eligible for Medicaid, this calculation still confirms that states agreeing to spending caps would be accepting substantial risk.

The block grant waivers pose particular risks for states that are considering using them to cover new groups of low-income adults, in lieu of taking up Medicaid expansion. That’s because these states would have no data on past expenditures to use in setting the initial cap, which would instead be set primarily based on national expenditure averages.[20]

The guidance requires such states to select a per-capita rather than an aggregate cap for the first two years of their waivers. But even so, they could end up with state costs that are far higher than they would be without the waiver. For example, a state for which initial per-enrollee costs came in just 10 percent higher than expected would end up spending nearly twice as much through a block grant waiver as under a standard expansion of Medicaid, all else equal.[21]

States that hit the caps would face pressure to reduce their Medicaid spending to offset the lost federal funding. That’s especially true since the caps are most likely to bind during recessions, public health emergencies, and other circumstances in which state budgets are already strained.

States could cut coverage and services for the adults subject to the guidance by using the new authorities it offers (described above).[22] Or, they could use existing authorities, for example cutting optional services (such as dental and vision), adopting burdensome enrollment and verification procedures that make it hard for eligible people to get and stay covered, or cutting payment rates for hospitals and physicians. States could also offset reduced federal funding for adults subject to the guidance by cutting spending on other groups. For example, a state could cut funding and increase waiting lists for home- and community-based services (such as home health aides), an important optional benefit for seniors and people with disabilities.

States would also face pressure to cut their Medicaid programs preemptively, to avoid any risk of hitting the caps, especially since nearly all states are subject to balanced budget requirements. So states adopting block grant waivers might take immediate steps to reduce enrollment or cut services.

Capped federal funding would also serve as a strong deterrent for states that are considering making changes that would expand or improve coverage but increase costs. For example, a state that opted into a block grant waiver with an aggregate funding cap would likely hesitate to streamline its eligibility procedures in ways that would cause more eligible people to enroll, since even a small increase in enrollment could cause its expenditures to exceed the cap. Likewise, states might hesitate to invest in new care coordination approaches that have the potential to improve outcomes and achieve reduced health care costs in the long run, but also have upfront costs.

States would theoretically have two safety valves to address federal funding cuts, but neither eliminates the risk to their budgets.[23]

First, the guidance notes that states could seek adjustments to their caps in the face of unexpected cost increases. But the Administration would have full discretion as to whether to approve such adjustments, and the guidance provides no clear criteria for how it would make such decisions.[24] States concerned that they will hit the cap during a recession or public health emergency are likely to feel that they have to initiate cuts, rather than counting on the Administration to exercise discretion to increase their funding.

Second, states adopting Medicaid waivers retain the right to terminate them. But unwinding the block grant waivers would not be straightforward: states should not expect to be able to simply opt out of these waivers for any year in which they would hit the funding cap. Given data lags and revisions, a state might not even know it was on track to hit the cap until the end of the year or even into the following year. States are then generally required to give CMS at least six months’ notice before terminating a waiver, and they are required to seek public comment before providing notice to CMS. CMS is also required to approve states’ waiver phase-down plans.

Moreover, a state unilaterally terminating a waiver would lose any associated authorities and funding arrangements. This could create a variety of challenges for state budgets, or in states where the legislation authorizing Medicaid expansion requires the state to secure certain limited waiver authorities to implement it. And if a state wanted to continue covering the people it was covering through the waiver, it would need to obtain separate authorization to do so from CMS before terminating the waiver.

The guidance creates an incentive for states to cut Medicaid even when they are not at risk of hitting their funding caps, through a new funding arrangement the Administration refers to as “shared savings.” This arrangement would effectively let states that opt for aggregate (versus per-person) caps redirect a limited amount of the federal savings from Medicaid cuts to other areas of their budgets, such as infrastructure or tax cuts, that have nothing to do with Medicaid’s goals. This funding arrangement would not change the fact that block grant waivers would likely reduce states’ federal funding — and it raises the likelihood that states taking the waivers would make cuts that would harm people with Medicaid.

For states accepting caps on their aggregate Medicaid funding, the guidance offers financial rewards for cutting Medicaid below the cap level. Specifically, a state that spent less than the cap in a given year could receive federal Medicaid funding the following year for programs that can’t usually be paid for through Medicaid. This federal funding would be capped at between 25 and 50 percent of the federal savings from the state’s Medicaid cuts.[25]

For example, suppose a state cuts $1 million from its Medicaid expansion. That cut would reduce federal spending by $900,000, since the federal government pays 90 percent of expansion costs. The state could claim between $225,000 and $450,000 of that amount as federal match for state costs not usually eligible for Medicaid funding, such as public health expenditures or work support services.

States would have to use some of these funds for new health or health-related programs, for which the state would have to provide matching funds at its standard Medicaid match rate. But the guidance explicitly allows states to use up to 30 percent of the federal funds available through the shared savings arrangement to supplant current state spending on health programs.

It gives the example of a state that is already funding a tobacco cessation program, which would not normally be eligible for federal Medicaid funding. If the state’s standard federal match rate is 67 percent, the state could use federal savings from Medicaid cuts to replace up to two-thirds of its current state spending on the tobacco cessation program and use the money it is currently spending on that program for any purpose it chooses. That effectively allows states to divert some federal Medicaid dollars to other parts of their budgets.[26]

The new funding arrangement would not change the fact that states should expect to receive less federal funding overall if they adopt block grant waivers. States would lose all of the federal matching funds they would normally receive for costs above the caps. They could repurpose only a portion of the federal savings from reducing their spending below the caps and could only claim those funds by providing state matching funds, some of which would have to be new state spending.

States should also recognize that “shared savings” would not be available to them until at least the second year of the waiver and sometimes not for several years beyond that. To be eligible for the new funding arrangement, states would first have to provide CMS with data on various performance measures that many states do not currently report; “shared savings” would not be available until at least two years after a state first reported these data. And states using block grant waivers to cover new populations would not be eligible for “shared savings” until at least the fourth year of a waiver, since they would have to adopt per capita caps for the first two years of the waiver, and the new funding arrangement would be available only for waivers with aggregate caps.

The proposed waivers likely violate federal law, and any state adopting them should expect to face costly, time-consuming litigation. The Administration itself reportedly expects the waivers will be challenged in court.[27]

The block grant guidance is breathtaking in scope, with the Administration asserting broad authority to overturn explicit statutory requirements for Medicaid eligibility, benefits, cost-sharing, and financing and essentially establish its own, alternative Medicaid program for adults. It claims it can do this by using what it known as “expenditure authority” authorization given by section 1115 of the Social Security Act to provide federal matching funds for expenditures that aren’t usually allowed under Medicaid, if these expenditures are needed to implement an “experimental, pilot or demonstration project … likely to assist in promoting the objectives of [Medicaid].”

Historically, the federal government has used expenditure authority to extend coverage to people who states were not otherwise allowed to cover through Medicaid. But in this case, the Administration would use it to offer coverage with additional eligibility restrictions, higher premiums and cost sharing, and fewer services to people states are free to cover in their standard Medicaid programs under options established by federal law.

Such waivers are likely to face challenges on two grounds. First, it is unclear how they would promote Medicaid’s objectives. As a federal court recently affirmed, Medicaid’s primary objective is to provide health coverage to low-income people. Block grant waivers would cover fewer people, with coverage that offers less financial protection and worse access to care, than the alternative in which states cover the same groups through their standard Medicaid programs.

Second, the guidance offers to exempt states from provisions of the Medicaid statute that the Administration lacks the authority to waive. For example, the Administration previously stated that it lacked the authority to let states institute closed formularies while also maintaining access to the Medicaid drug rebate program. It now proposes to do exactly that.[28]

The Administration’s argument appears to be that it can use expenditure authority to provide coverage that is not subject to the same statutory requirements that govern other Medicaid coverage. But legal experts have questioned that claim, concluding that these requirements still apply and would therefore be violated by the proposed waivers.[29]