The July 20 version of the Senate Republican health bill[1] to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would cause 22 million people to lose coverage by 2026 and drive $756 billion in federal Medicaid cuts over the next ten years, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) found today.[2] This means this version of the bill would result in the same number of people losing their health insurance coverage as under the prior version of the Senate bill. It also means that the bill would continue to reverse nearly all of the historic coverage gains achieved since the ACA was enacted in 2010. The CBO estimate confirms that the bill’s fundamental flaws — including causing tens of millions of Americans to lose their health coverage and instituting draconian cuts to the Medicaid program — still have not been addressed.[3]

First in the House, and now in the Senate, we have seen Republican leaders revise their bill and claim that the revisions address the core flaws. And on both occasions, CBO has shown that those claims were false. In addition, today’s CBO estimate does not incorporate the coverage effects of the so-called Cruz amendment, which is expected to be included in the final version of the Senate Republican bill and which would likely lead to severe destabilization of the individual market and sharply higher premiums for people with pre-existing conditions, as insurers, actuaries, and outside analysts all warn.[4] It’s therefore critical that the Senate not consider any final version of its bill until CBO issues a comprehensive analysis of the bill’s impact on coverage and affordability, incorporating the effects of the Cruz amendment and any other modifications.

The revised bill — known as the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 (BCRA) — would still effectively end the ACA’s Medicaid expansion starting in 2021 and radically restructure Medicaid by converting virtually the entire program to a per capita cap starting in 2020. It would also sharply cut the ACA’s marketplace tax credits and subsidies in 2020 — a cut of $427 billion over ten years relative to current law — and immediately end the ACA’s individual and employer mandates to buy and provide health coverage, respectively. The Senate bill would require insurers to impose a six-month waiting period on individuals who don’t maintain continuous coverage. It would also permit states to obtain waivers to eliminate the ACA requirement that insurers cover essential health benefits like prescription drugs and mental health treatment, which would also allow the return of annual and lifetime coverage limits. States could also waive the ACA requirement setting an annual limit on out-of-pocket costs. The bill would also drop the bar against insurers charging older people more than three times what they charge younger people. Lastly, the July 20 revised bill does not include the Cruz amendment, which would allow insurers to offer plans that charge higher premiums or deny coverage outright to people with pre-existing conditions as long as they offer one plan that complies with remaining ACA standards and consumer protections, although some form of that amendment is expected to be included in any final bill considered by the Senate.

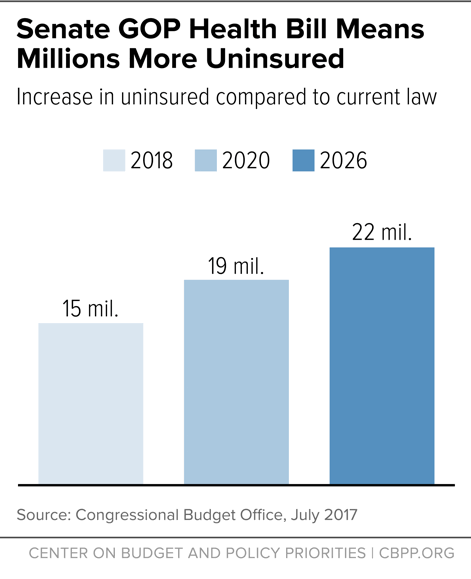

In 2018, the number of uninsured would rise by 15 million, relative to current law. That number would further rise to 19 million by 2020. By 2026, the number of uninsured would increase by 22 million — or nearly 79 percent higher than under current law. (See Figure 1.) This means that, by 2026, the historic coverage gains achieved under the ACA would still nearly all be eliminated and the resulting uninsured rate among the non-elderly would be about the same as the 2010 level.

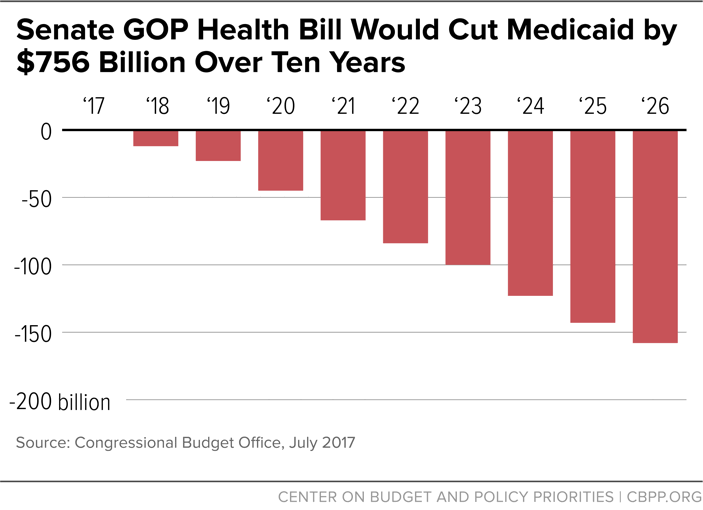

Federal Medicaid spending would be cut by $756 billion or 15 percent over the next ten years, relative to current law, which is similar to the CBO estimate of the Medicaid provisions of earlier version of the Senate bill. That’s because the latest version did not make any significant changes to the bill’s major Medicaid elements:[5] the effective elimination of the Medicaid expansion starting in 2021[6] and conversion of Medicaid to a per capita cap starting in 2020. (States would also have the option of a Medicaid block grant for adults including expansion adults.)

By 2026, the annual cut in federal spending would rise to $158 billion, a reduction of more than one-quarter, relative to current law. (See Figure 2.) According to CBO, about three-quarters of the cut in 2026 are the result of the end of the Medicaid expansion and one-quarter from the Medicaid per capita cap. That’s still $8 billion larger than even under the House bill, because the Senate bill further lowers the growth rate for federal funding under the per capita cap to the general inflation rate starting in 2025, below the House bill’s already inadequate level.[7]

As a result, the number of Medicaid beneficiaries would fall by 15 million in 2026, or 1 million more than under the House bill. Most of those losing Medicaid would likely end up uninsured. As CBO has previously noted, while “those people would instead be eligible for a premium tax credit under this legislation … because of the expense for premiums and the high deductibles most of them would not purchase insurance….”[8] For example, CBO finds that for an individual at 75 percent of the federal poverty line, the expected $13,000 deductible under a plan that could be purchased through the premium tax credit would more than exceed such an individual’s annual income.

Also, CBO has previously expected that the “gap [between Medicaid spending under current law and under the Senate bill] would continue to widen because of the compounding effect of the differences in spending growth rates” between the per capita cap and states’ actual Medicaid spending needs. As a result, the federal Medicaid spending cut under the Senate bill would rise to 35 percent by 2036.[9] That would translate to a federal Medicaid spending cut of $2.6 trillion in the second decade, according to rough estimates from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.[10] CBO thus expected that after 2026 that “enrollment in Medicaid would continue to fall relative to what would happen under current law.” Because, as noted, the revised Senate bill did not include any significant changes to its provisions related to the Medicaid expansion and the per capita cap, these long-term estimates would be virtually unchanged.

Similar to the prior version of the Senate bill, the revised bill would cut marketplace subsidies by $427 billion over the next ten years, relative to current law. As a result, marketplace enrollees receiving subsidies would face significantly higher premiums and other out-of-pocket costs.[11] Today, premium tax credits are based on the value of “silver plan” coverage: coverage with a 70 percent actuarial value. Under the Senate bill, tax credits would instead be based on the cost of a plan with an actuarial value of 58 percent. According to CBO, such a plan in 2026 would have a deductible of roughly $13,000 with individuals responsible for 20 percent of all costs thereafter.

As a result, CBO finds that because of the reduction in subsidies and higher premiums for plans of comparable value, there would be a “decrease in the number of lower-income people with coverage through the nongroup market under this legislation, compared with the number under current law.” CBO also notes that because “a deductible of $13,000 would be a large share of their income, many people with low income would not purchase any plan even if it had very low premiums — on net, after accounting for premium tax credits….”[12]

The bill also rearranges the current tax credit schedule, generally reducing premium tax credits for older people while increasing them for younger people. And it eliminates tax credits entirely for people with incomes between 350 percent and 400 percent of the poverty line — about $42,000 to $48,000 for a single person. For example, according to CBO, a 64-year-old with income at 375 percent of the federal poverty line would have to pay $11,500 more in premiums in 2026 for a silver plan because he would no longer be eligible for subsidies (though he could qualify for a tax deduction under the Senate bill’s provisions allowing funds in Health Savings Accounts to be withdrawn to pay for premiums).[13]

Finally, like the House bill, the Senate bill would eliminate the ACA’s cost-sharing subsidies, which help lower deductibles and copayments for low-income marketplace enrollees, and would not replace them. This means that the typical deductible would jump from about $800 to $13,000 for a person with income at 175 percent of the federal poverty line in 2026. Such a deductible would equal nearly half his annual income.

Today’s estimate confirms that older low-income individuals would still be particularly hard hit. CBO finds that a typical 64-year-old with income at 175 percent of the federal poverty line would pay in 2026, on average, $3,800 more in premiums in 2026 than under current law to purchase a silver plan, while also having to pay roughly $12,200 more in deductibles (as well as higher other out-of-pocket costs) because he would no longer be eligible for cost-sharing reductions. That’s why CBO concludes that “a larger share of enrollees in the nongroup market would be younger people and a small share would be older people than would be the case under current law.”

Notably, CBO’s estimates focus on the average impact nationwide and do not take into account how residents of high-cost states would experience even larger, unaffordable increases in their premiums and other out-of-pocket costs. That’s because the across-the-board cuts to the premium tax credits would be larger in these states than in other states. In states where health costs — and hence premiums — are high, the difference in premiums between more and less generous coverage also is greater.

CBO does not reestimate the effects of the Senate bill’s provisions to dramatically expand “section 1332” waivers. But presumably its earlier estimates all still apply: states with about half of the nation’s population would still take up the waivers primarily to eliminate or weaken the ACA requirement that insurers cover essential health benefits. States could also once again permit insurers to impose annual and lifetime limits, charge much higher out-of-pocket costs without limit and no longer offer lower deductible, more comprehensive plans.[14] These waivers, in turn, would lower the premium subsidies that would otherwise be spent, with states using these “pass-through” savings to help stabilize the health insurance market or provide subsidies in different ways. In a small fraction of the affected population, as CBO previously warned, these changes would actually result in fewer people insured because subsidies would be redirected to individuals who would otherwise already purchase coverage or to purposes other than health insurance coverage.

As CBO noted in its earlier analysis of similar provisions in the House-passed bill, people living in such states could experience “substantial increases in out-of-pocket spending on health care or would choose to forgo the services” entirely. Such excluded services would include: maternity care, mental health and substance use disorder treatment, rehabilitative and habilitative services, and pediatric dental care. CBO notes that out-of-pocket costs associated with maternity care and mental health and substance abuse services could increase “by thousands of dollars” and that annual and lifetime limits on benefits would also no longer apply.

Those with the greatest health care needs would see their out-of-pocket payments rise the most in states that eliminated or substantially altered the essential health benefits requirement.

As noted, the CBO estimate does not include the effects of the Cruz amendment, which would allow insurers that offer at least one “community-rated” plan (that is, a plan where premiums would not vary based on health status) to offer additional plans subject to “medical underwriting” (plans for which insurers could vary premiums based on health history, deny coverage outright to people with expensive pre-existing conditions, or exclude coverage or impose waiting periods for pre-existing conditions).[15] Under such a system, healthier people would naturally gravitate toward underwritten plans, which would offer them lower premiums. Meanwhile, the community-rated plans would disproportionately enroll people with expensive pre-existing conditions, and insurers would price them accordingly.

This “adverse selection” means that, in practice, people with pre-existing conditions would face sharply higher premiums because of their health status, whether they purchased “underwritten” or “community-rated” plans. While lower-income people would be partially protected from higher premiums by the Senate bill’s subsidies, people with pre-existing conditions with incomes over 350 percent of the poverty level (about $42,000 for a single adult) would face high, sometimes unaffordable premiums, with the only assistance made available through allowing funds in Health Savings Accounts to be used to pay premiums. That assumes, however, that such individuals would have the financial ability to make sufficient contributions and pay premiums in full on an upfront basis, in order to get a relatively modest tax deduction when they file their taxes the following year. As a result, the Cruz amendment could drive up CBO’s estimate of the increase in the number of uninsured under the Senate bill.

Overall premiums in the individual market would rise by 20 percent in 2018 and 10 percent in 2019, relative to current law, due to the immediate repeal of the individual mandate as fewer healthy, lower-cost people enroll. In addition, total individual market enrollment would shrink by 7-8 million in these years, relative to current law. Moreover, after 2019, CBO continues to expect that a fraction of the population will reside in areas where no insurers would participate in the individual market or the only insurance available would charge very high premiums. This would be due to both the reduction in the subsidies and the deterioration of the risk pool as fewer healthy people enrolled.

These premium increases would likely be much higher if CBO had incorporated the effects of the Cruz amendment. That’s because CBO instead assumed that all of the $70 billion in additional funding the Cruz amendment uses to address the resulting destabilization of the individual market[16] would instead be used to increase reinsurance payments to health insurers in order to lower premiums in the absence of the Cruz amendment. According to CBO, premiums would be about 5 percent lower as a result of the additional stabilization funding, which would increase the number of people purchasing individual market coverage. But if the CBO estimate had included the Cruz amendment, it likely would find that it would destabilize the individual market, result in higher premiums, and potentially fewer people with access to affordable coverage overall.