Michigan’s Waiver Proposal Would Undermine Its Successful Medicaid Expansion

End Notes

[1] State of Michigan, Healthy Michigan Plan Enrollment Statistics as of October 15, 2018, https://www.michigan.gov/mdhhs/0,5885,7-339-71547_2943_66797---,00.html.

[2] Michigan House Fiscal Agency, “Legislative Analysis on Healthy Michigan Work Requirements and Premium Payment Requirements,” June 6, 2018, http://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2017-2018/billanalysis/House/pdf/2017-HLA-0897-5CEEF80A.pdf.

[3] Jennifer Wagner, “4,109 More Arkansans Lost Medicaid in October for Not Meeting Rigid Work Requirements,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 16, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/4109-more-arkansans-lost-medicaid-in-october-for-not-meeting-rigid-work-requirements.

[4] State of Michigan, “Section 1115 Demonstration Extension Application: Healthy Michigan Plan (Project No. 11-W-00245/5),” September 10, 2018, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/mi/mi-healthy-michigan-pa3.pdf. Michigan’s Medicaid expansion requires beneficiaries to make monthly payments, which are based on the average co-payments for services used in the previous six months, into a health savings account. In addition to these monthly payments, beneficiaries with incomes between 100 and 138 percent of the poverty level must pay monthly premiums set at 2 percent of their incomes.

[5] For more information on the benefits of Medicaid expansion, see Larisa Antonisse et al., “The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review,” Kaiser Family Foundation, March 28, 2018, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/, and Government Accountability Office, “Medicaid: Access to Health Care for Low-Income Adults in States with and without Expanded Eligibility,” October 15, 2018, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-607.

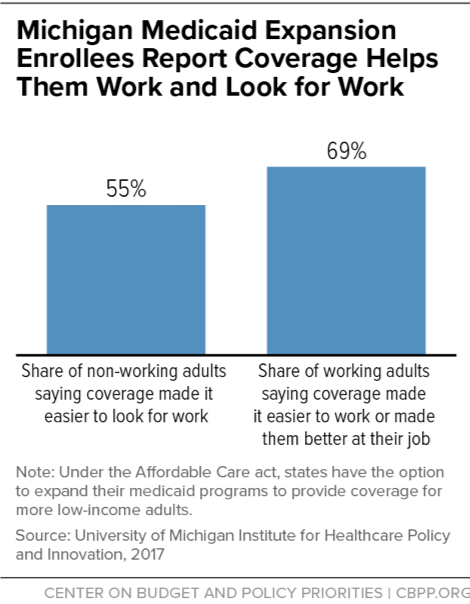

[6] Susan Dorr Goold and Jeffrey Kullgren, “Report on the 2016 Healthy Michigan Voices Enrollee Survey,” University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy & Innovation, January 17, 2018, https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/2016_Healthy_Michigan_Voices_Enrollee_Survey_-_Report__Appendices_1.17.18_final_618161_7.pdf.

[7] Institute for Healthcare Policy & Innovation, “Medicaid Expansion Helped Enrollees Do Better at Work or in Job Searches,” University of Michigan, June 27, 2017, http://ihpi.umich.edu/news/medicaid-expansion-helped-enrollees-do-better-work-or-job-searches.

[8] Renuka Tipirneni, Susan D. Goold, and John Z. Ayanian, “Employment Status and Health Characteristics of Adults With Expanded Medicaid Coverage in Michigan,” Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine, April 2018, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/article-abstract/2664514?redirect=true.

[9] Melvin Stephens, Jr., and Desmond J. Toohey, “The Impact of Health on Labor Market Outcomes: Experimental Evidence from MRFIT,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, January 2018, http://www.nber.org/papers/w24231.

[10] State of Michigan, “Section 1115 Demonstration Extension Application: Healthy Michigan Plan (Project No. 11-W-00245/5).”

[11] Renuka Tipirneni et al., “Primary Care Appointment Availability and Nonphysician Providers One Year After Medicaid Expansion,” American Journal of Managed Care, June 2016, Vol. 22, No. 6, pp. 427-31, https://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2016/2016-vol22-n6/primary-care-appointment-availability-and-nonphysician-providers-one-year-after-medicaid-expansion.

[12] State of Michigan, “Section 1115 Demonstration Extension Application: Healthy Michigan Plan (Project No. 11-W-00245/5).”

[13] Eric Charles et al., “Impact of Medicaid Expansion on Cardiac Surgery and Outcomes,” Annals of Thoracic Surgery, October 2017, Vol. 104, No. 4, pp. 1251-1258.

[14] Sarah Miller et al., “The ACA Medicaid Expansion in Michigan and Financial Health,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 25053, September 2018, http://www.nber.org/papers/w25053.pdf.

[15] Goold and Kullgren.

[16] Michigan House Fiscal Agency, “Healthy Michigan Plan Saving and Cost Estimates,” September 14, 2016, http://www.house.mi.gov/hfa/PDF/HealthandHumanServices/HMP_Savings_and_Cost_Estimates.pdf.

[17] John Z. Ayanian et al., “Economic Effects of Medicaid Expansion in Michigan,” New England Journal of Medicine, February 2, 2017, Vol. 376, No. 5, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1613981.

[18] Thomas Buchmueller et al., “2016 Report on Uncompensated Care and Insurance Rates, December 21, 2017,” https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/2013_PA_107_Section_105d8-9_Required_Report_2017_618079_7.pdf; Jessica Schubel and Matt Broaddus, “Uncompensated Care Costs Fell in Nearly Every State as ACA’s Major Coverage Provisions Took Effect,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 23, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/uncompensated-care-costs-fell-in-nearly-every-state-as-acas-major-coverage.

[19] Michigan proposes to exempt the following groups: parents with children under age 6, beneficiaries receiving disability benefits, pregnant women, full-time students, parents or caretakers of family members with a disability, those medically frail, beneficiaries with a medical condition that results in a work limitation (requires medical professional order), beneficiaries who have been incarcerated within the last six months, beneficiaries receiving unemployment benefits, and beneficiaries under age 21 who had previously been in foster care.

[20] Beneficiaries are allowed three months of noncompliance within a 12-month reporting period.

[21] Michigan House Fiscal Agency, “Legislative Analysis on Healthy Michigan Work Requirements and Premium Payment Requirements.”

[22] Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and MaryBeth Musumeci, “Implications of a Medicaid Work Requirement: National Estimates of Potential Coverage Losses,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 27, 2018, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/implications-of-a-medicaid-work-requirement-national-estimates-of-potential-coverage-losses/. To reach their estimates on the impact of work requirements on people who should remain eligible, Kaiser researchers looked at evidence on how administrative requirements affect Medicaid enrollment, which shows that increased red tape causes eligible people to lose coverage. Kaiser researchers applied a low disenrollment rate of 5 percent and a high of 15 percent to the groups of people who are already working or should be exempt based on this evidence.

[23] Wagner, 2018.

[24] Tipireni, Goold, and Ayanian.

[25] For an explanation of the methodology behind these estimates, see Aviva Aron-Dine, Raheem Chaudhry, and Matt Broaddus, “Many Working People Could Lose Coverage Due to Work Requirements,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 11, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/many-working-people-could-lose-health-coverage-due-to-medicaid-work-requirements.

[26] Goold and Kullgren.

[27] LaDonna Pavetti, Michelle Derr, and Heather Hesketh, “Review of Sanction Policies and Research Studies,” Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., March 2003.

[28] For more information on how a Medicaid work requirement would harm specific populations, see https://www.cbpp.org/medicaid-briefs-who-is-harmed-by-work-requirements.

[29] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “How Medicaid Work Requirements Will Harm Older Americans,” February 20, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/how-medicaid-work-requirements-will-harm-older-americans.

[30] Michigan House Fiscal Agency, “Healthy Michigan Plan Saving and Cost Estimates.”

[31] Samantha Artiga, Petry Ubri, and Julia Zur, “The Effects of Premiums and Cost-Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2017, http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-The-Effects-of-Premiums-and-Cost-Sharing-on-Low-Income-Populations.

[32] The Lewin Group, “Indiana Healthy Indiana Plan 2.0: Interim Evaluation Report,” July 6, 2016, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/in/Healthy-Indiana-Plan-2/in-healthy-indiana-plan-support-20-interim-evl-rpt-07062016.pdf.

[33] See LaDonna Pavetti, “Work Requirements Don’t Work,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 10, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/work-requirements-dont-work; Pavetti, “Work Requirements Don’t Cut Poverty, Evidence Shows,” CBPP, updated June 7, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/work-requirements-dont-cut-poverty-evidence-shows; and Pavetti, “Evidence Doesn’t Support Claims of Success of TANF Work Requirements,” CBPP, April 3, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/evidence-doesnt-support-claims-of-success-of-tanf-work-requirements. See also Ed Dolan, “Do We Really Want Expanded Work Requirements in Non-Cash Welfare Programs?” Niskanen Center, July 23, 2018, https://niskanencenter.org/blog/expanded-work-requirements-in-non-cash-welfare-programs/.

[34] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services letter to state Medicaid directors (18-002), January 11, 2018, https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd18002.pdf.

[35] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Healthcare benefits: Access, participation, and take-up rates,” https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2017/ownership/civilian/table09a.htm.

[36] Michelle Long et al., “Trends in Employer-Sponsored Insurance Offer and Coverage Rates, 1999-2014,” Kaiser Family Foundation, March 21, 2016, https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/trends-in-employer-sponsored-insurance-offer-and-coverage-rates-1999-2014/.

[37] CBPP calculations from Current Population Survey data for 2016.

[38] Goold and Kullgren.

[39] Hannah Katch, Jennifer Wagner, and Aviva Aron-Dine, “Medicaid Work Requirements Will Reduce Low-Income Families’ Access to Care and Worsen Health Outcomes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated August 13, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-work-requirements-will-reduce-low-income-families-access-to-care-and-worsen.

[40] Goold and Kullgren.