The Trump Administration’s approval of Kentucky’s demonstration project or “waiver” under section 1115 of the Social Security Act — which came just a day after the Administration announced that it would let states condition Medicaid coverage on work — confirms its intention to let states deviate from Medicaid rules in ways that will reduce the number of people with health coverage and make it harder for those covered to get care.[1] The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) approved Kentucky’s waiver under its new waiver criteria, which no longer include increasing and strengthening coverage or improving health outcomes for low-income people.[2]

Kentucky is the first state that HHS has allowed to make participation in work or work-related activities a requirement for Medicaid eligibility. Sylvia Mathews Burwell, who served as President Obama’s HHS Secretary, denied such requests because work requirements are inconsistent with Medicaid’s purposes.[3] Kentucky is also the first state that HHS has allowed to lock people, including poor people, out of coverage if they don’t complete their renewal paperwork on time or don’t report changes in income or hours of employment that affect their eligibility. Indeed, as explained below, failing to report even very small income changes could cost someone his or her coverage for six months. These actions — along with other waiver provisions that impose premiums, eliminate coverage of dental and vision services, end retroactive coverage, and otherwise make it harder for people to get and maintain coverage — will likely reduce Medicaid enrollment and make it harder for those enrolled to get care. The waiver will also increase paperwork and red tape, not just for beneficiaries but also for providers who must collect co-pays, and managed care organizations, which must bill and collect monthly premiums.

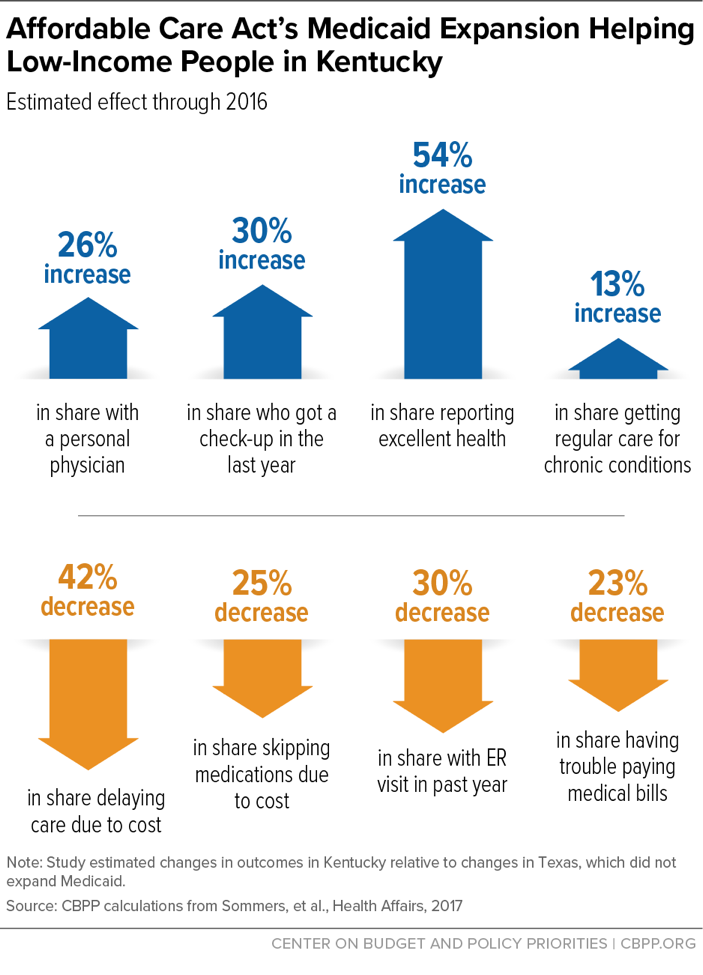

The waiver puts at risk the remarkable success of Kentucky’s Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The percentage of uninsured low-income Kentuckians with incomes under 138 percent of the poverty line — the income eligibility level under the Medicaid expansion — dropped from 40 percent in 2013 to 7.4 percent at the end of 2016. And coverage gains are improving access to care, health, and financial security, growing evidence shows, as low-income Kentuckians report that they’re less likely to skip medication due to cost, less likely to have trouble paying medical bills, and likelier to get regular care for their chronic health care conditions than before the expansion.[4] (See Figure 1.)

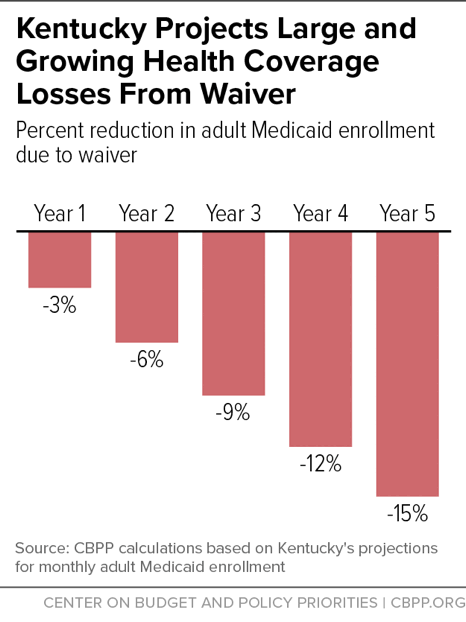

Under the waiver, however, Kentucky projects a 15 percent drop in adult Medicaid enrollment by the fifth year. (See Figure 2.) Specifically, it projects 1.14 million lost coverage months: the equivalent of nearly 100,000 people losing coverage for a full year or, more likely, well over 100,000 people experiencing gaps in coverage due to lock-outs for failing to meet work requirements, pay premiums, or report changes or renew coverage in a timely manner.

HHS’ approval of Kentucky’s waiver also sends a dangerous signal to low-income people in states such as Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Utah, and Wisconsin, where similar — in some cases even harsher — proposals are pending.[5] The HHS Secretary can let states deviate from certain Medicaid provisions, but HHS is supposed to grant such waivers only to the extent necessary to implement demonstration projects that promote Medicaid’s objectives to furnish health care services to low-income individuals.[6] Waivers should enhance coverage and improve the delivery of care. They shouldn’t let states make changes to Medicaid that hurt beneficiaries by causing them to lose coverage or make it harder for them to get health care.[7]

Kentucky’s proposal, called Kentucky HEALTH (Kentucky Helping to Engage and Achieve Long-Term Health), will change the state’s Medicaid program for parents and non-disabled adults under 65 in significant ways once its implementation starts this July.

- Work requirement. Most adult beneficiaries who aren’t pregnant, primary caretakers of a dependent child, or full-time students must work, volunteer, search for a job, or participate in job training or other approved activity for at least 80 hours a month to receive their benefits unless they’re already working 30 hours a week. Beneficiaries must document their participation in one or more activity on “at least a monthly basis.”[8] Beneficiaries who don’t comply with the participation requirement in any month are suspended unless they make up the hours they were short or participate in a health or financial literacy course the following month. Beneficiaries who are “medically frail” are supposed to be exempt from the requirement, but the exemption won’t be automatic for all who qualify. Many people will have to prove they are exempt, and many with disabilities won’t meet the strict medically frail definition.[9]

- Premiums and co-pays. All adult beneficiaries — including those with incomes below the poverty line — must pay premiums that range from $1 to $15 a month, depending on income. The waiver gives Kentucky unprecedented authority to raise those premiums to up to 4 percent of household income without seeking federal permission. For an individual with income at the poverty line ($12,060 in 2017), a premium of 4 percent of income would be $40 a month. For people above the poverty line, their enrollment won’t be effective until they pay their first month’s premium. If they fall 60 days behind on their premium payments, they will lose coverage for six months. (They can re-enroll if they pay their past-due premiums and take a financial or health literacy course.) People below the poverty line who don’t pay won’t have coverage for up to 60 days, after which they’ll be enrolled in a plan without premiums but with co-payments.

- Lockouts for failing to complete paperwork and report changes. Beneficiaries at any income level who don’t complete their annual redeterminations of eligibility within the required timeframe and those who don’t report changes in income, work, or work-related activities that affect their eligibility will lose coverage for six months.

- Deductible accounts. Beneficiaries will enroll in health plans that carry a $1,000 deductible (unlike regular Medicaid and Kentucky’s current program, which has no deductible) and that lack coverage for dental and vision care and non-emergency medical transportation, which Kentucky’s current Medicaid program covers. All beneficiaries will receive a $1,000 state-funded account to pay the deductible.

- Rewards accounts. Beneficiaries who pay premiums will have a separate “My Rewards Account” into which the state will make deposits if the beneficiaries complete “certain state-specified healthy behaviors,” exceed the 80 hours a month minimum for “community engagement activities,” or go a full year without using the emergency room for a non-emergency reason. The state will also shift up to half of any balance that remains in an enrollee’s deductible account (described above) at the end of a year to the individual’s rewards account, and will deduct funds from the rewards account if an enrollee goes to the emergency room for non-emergency care, misses appointments, or fails to pay a premium within 60 days. Enrollees can use the rewards account to help pay for vision and dental care, over-the-counter drugs, or a gym membership.

- Eliminating retroactive coverage. As noted, even beneficiaries below the poverty line may have to wait two months for coverage if they can’t afford their premiums. The waiver also eliminates retroactive coverage, which pays providers for medical costs that beneficiaries incurred up to three months before enrolling in Medicaid if they were eligible for Medicaid during that period. Retroactive coverage increases financial security for beneficiaries by preventing medical bankruptcy, and it helps ensure the financial stability of health providers by paying for medical services that would otherwise go uncompensated.[10]

- Eliminating non-emergency medical transportation. The waiver eliminates coverage for non-emergency medical transportation, a Medicaid benefit that ensures that people with limited transportation options can get to the doctor and other health care providers.

Kentucky projects that the waiver will save the state and federal governments $2.2 billion over five years. That’s because significantly fewer people will have Medicaid coverage (and, many thus, will likely end up uninsured). The state projects a 3 percent decline in adult Medicaid enrollment in the first year of the waiver, growing to 15 percent by the fifth year. (See Figure 2.) The projected reductions in coverage months are equivalent to almost 20,000 people losing coverage for a full year in the first year of the waiver — and almost 100,000 by the fifth year, including almost 80,000 Medicaid expansion enrollees and 20,000 parents and caretakers who were eligible for Medicaid before Kentucky’s Medicaid expansion.[11] In practice, even more people will likely be affected, with many experiencing disruptive coverage gaps of less than a full year.

Kentucky’s Medicaid expansion has led to improvements in access to care, health, and financial security, studies find. For those losing coverage, these gains will be lost.

Large projected coverage losses under the waiver aren’t surprising, given that many of its features will make it harder for people to get and maintain coverage. Premiums alone will shrink participation in Medicaid, with the largest impact on the lowest-income people, a robust body of research shows. Due to premiums, some people don’t enroll at all and others can’t maintain their participation.[12] In Indiana, the model for Kentucky’s waiver, 55 percent of individuals either never made a first payment or missed a payment while enrolled.[13] As in Kentucky, people in Indiana with incomes below the poverty line who don’t make a payment are enrolled in a plan with co-pays. Those with incomes above the poverty line are either never enrolled or their coverage is terminated, depending on the timing of the non-payment. But the impact of premiums in Kentucky could be much greater because HHS gave the state permission to charge people as much as 4 percent of their income.

Coverage loss will result not just from premiums but from other unprecedented changes that HHS is letting Kentucky make, including the work requirement and ending coverage for people who don’t complete their renewals or report changes in a timely manner.

- Requiring work as a condition of eligibility. Almost two-thirds of adult Medicaid enrollees in Kentucky work, and over half of those who don’t are ill or disabled.[14] Since Kentucky’s proposal shouldn’t affect those who are working, and it includes an exemption for the medically frail, the work requirement wouldn’t seem to affect very many beneficiaries. In fact, however, experience from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance program and from SNAP (food stamps) shows that considerable numbers of people who were working or should have qualified for exemptions from work requirements lost benefits because they didn’t complete required paperwork or couldn’t document their eligibility for exemptions. People struggling with mental health or substance use disorders or other chronic conditions may have particular problems either meeting work requirements or proving that they qualify for exemptions: in fact, a study of state TANF programs showed that people with disabilities were disproportionately likely to be sanctioned for not meeting work requirements.[15] Kentucky’s work requirement, which requires monthly reporting of work activities, will likely mean that people with serious health needs will lose access to treatment. Moreover, majorities of adults who gained health coverage after Medicaid expansions in Michigan and Ohio said that their coverage helped them look for work or remain employed.[16] Losing coverage — and, with it, access to mental health and substance use disorder treatment, medication to manage chronic conditions, or other important care — could have the perverse result of impeding future employment.

- Disenrollment for failing to renew eligibility on a timely basis. In rejecting a similar proposal from Indiana in 2016, HHS recognized that many low-income individuals face challenges in completing the renewal process such as language access and problems getting mail. HHS also found that mental illness or homelessness can make completing the renewal process difficult and that coverage gaps could cause harm.[17] For these and other reasons, HHS found that penalizing people for not completing their renewals didn’t promote Medicaid’s objectives. By reversing course, this Administration is opening the door to hurting beneficiaries, particularly some of the most vulnerable.

- Disenrollment for failing to report changes. Beneficiaries who don’t report changes in income, employment, and other circumstances that affect their eligibility will lose coverage and not be able to re-enroll for six months unless they complete a financial or health literacy course. Medicaid beneficiaries generally know that they must report income changes that would make them lose their Medicaid eligibility such as higher pay from a new job, but — unique to Kentucky’s waiver — beneficiaries will have to determine when they need to report changes affecting their premium obligation, access to employer-sponsored insurance, or any factors regarding their compliance with the community engagement requirement, all which could affect their eligibility. Take someone below the poverty line, for instance, with $990 of monthly income and enrolled in the co-payment plan because she didn’t pay a premium. If her income rose just to $1,010 a month, putting her above the poverty line, she would have to pay a premium in order to stay covered.[18] If she failed to report that minor income change, she could find herself without coverage for up to six months.

As noted, beneficiaries with income below the poverty line who don’t pay premiums will have to pay co-payments, including for doctor’s visits and prescription drugs. Even relatively small co-payments of $1 to $5 reduce low-income people’s use of necessary health care services, research shows.[19] In Indiana, people in the “Basic” plan with co-pays were likelier to use the emergency room, less likely to get preventive and primary care, and adhered less to their prescription drug regimens for chronic conditions such as asthma, arthritis, and heart disease than those in the “Plus” plan without co-pays.[20] One-third of Indiana’s waiver enrollees were in “Basic,” including half of all African Americans in the program.

Under Kentucky’s waiver, beneficiaries will also lose the vision and dental coverage that the current Medicaid program includes. As described above, they will receive a “My Rewards Account” to help them pay for vision and dental care, among other things. Half of any balance remaining in an enrollee’s deductible account at year-end will roll over to the rewards account.

But the rewards account is an empty promise for the many people who will use at least $1,000 in health care services over the course of a year (the amount that the state will deposit in beneficiaries’ regular accounts to pay their $1,000 deductible), thus leaving nothing to roll over to the rewards accounts. Kentucky has experienced a 740 percent increase in substance use treatment services from 2014 through mid-2016; those receiving them likely use at least $1,000 worth of health care a year, leaving them with nothing in their rewards account. Similarly, people with diabetes or hypertension would likely use up their regular account for regular monitoring and treatment. At the same time, there’s a real danger that people needing dental or vision care would pay for it by forgoing necessary health care services.

Some vision and dental providers may stop providing care to Medicaid beneficiaries, leaving people unable to get care even if they have funds in their accounts. Providers have to check each beneficiary’s account in advance to see if it has enough funds to cover a beneficiary’s needed care. In many cases, however, the provider won’t know what care a beneficiary needs before seeing the person. Rather than risk not getting paid, some providers may stop participating in Medicaid.

Making it harder for people to stay covered and get care doesn’t promote Medicaid’s objectives, and Kentucky’s waiver will hurt many Kentuckians now enrolled or eligible for coverage. Seema Verma helped Kentucky design its proposal before she became the current Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, an HHS agency that does the work related to Medicaid waivers. She has said that the ACA’s Medicaid expansion to low-income adults “does not make sense,” and the Administration and congressional Republicans spent much of last year trying to repeal it.[21] Kentucky’s waiver shows that the Administration will use waiver authority to undermine coverage for low-wage workers and other low-income adults for whom the Medicaid expansion has improved access to health care and their financial well-being. HHS’ approval of Kentucky’s waiver threatens to roll back the state’s impressive coverage gains due to the Medicaid expansion, and it portends a similar pattern in other states that have requested waivers of key components of the Medicaid statute.