A new Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) presentation purports to show that the Consumer Freedom Amendment (“Cruz amendment”) to the Senate health bill would reduce individual market premiums, including for people buying comprehensive coverage.[1] In reality, HHS’s own analysis suggests the opposite: the Cruz amendment would almost certainly increase premiums for comprehensive plans. The analysis masks that conclusion only by making flawed assumptions, ignoring other aspects of the Senate bill, and comparing apples and oranges.

The Cruz amendment would let insurers that offer “ACA [Affordable Care Act] compliant” plans (plans subject to the ACA’s requirements that premiums not vary based on one’s health status) also offer “non-ACA compliant” plans (plans for which they could charge higher premiums or deny coverage based on health history). Under such a system, healthier people would naturally gravitate toward non-ACA compliant plans, which would offer them lower premiums.[2] Meanwhile, ACA- compliant plans would disproportionately enroll people with expensive pre-existing conditions, and insurers would price them accordingly. As a result, insurers, state regulators, and independent experts have all concluded that the amendment would fuel large increases in premiums for ACA- compliant plans, likely putting coverage out of reach for many people with pre-existing health conditions.[3]

The HHS presentation does not disclose many of its key assumptions — claiming they’re “proprietary” — which makes it hard to fully disentangle why its findings are so inconsistent with those of other analysts. Nonetheless, the following points are clear.

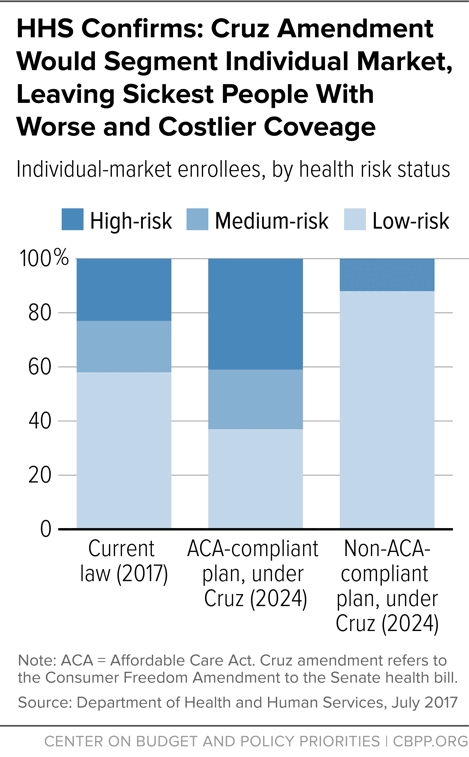

Like other analysts, HHS finds that the Cruz amendment would segment the market, with an overwhelming share of sicker people enrolling in comprehensive coverage. As shown in slide 14 of the presentation, under current law, comprehensive plans enroll a relatively balanced risk pool: a mix of healthier and sicker individuals, as shown in the figure below. HHS’s own projections show that the Cruz amendment would dramatically change that: more than 40 percent of those buying comprehensive plans would have “high” medical risk. That’s because nearly 70 percent of those with “low” medical risk — and zero percent of people with “high” medical risk — would end up buying non-ACA-compliant plans. With a much sicker risk pool in the ACA-compliant market, premiums would almost certainly have to rise.

The premium comparisons that HHS presents are meaningless, comparing apples and oranges; an apples-to-apples comparison would likely show higher ACA-compliant premiums as a result of the Cruz amendment. Slide 12 of the HHS presentation compares weighted average premiums under current law — i.e., average premiums across the full age distribution, including older people — with benchmark “silver plan” premiums for a 40-year-old under the Cruz amendment. In 2017, enrollment-weighted average premiums for marketplace plans are about 30 percent higher than the average benchmark “silver plan” premium, indicating that an apples-to-apples comparison would show either higher premiums or a far smaller decrease under the Cruz amendment compared to current law.[4]

On top of that, HHS does not in fact compare current-law premiums to premiums under the Senate bill with the Cruz amendment in place; instead, it cherry picks features of the Senate bill and features of current law to skew its analysis and make it look more favorable to the Cruz amendment.

- The analysis takes into account the Senate bill’s provision allowing insurers to charge older people premiums that are five times higher than for younger people, which lowers premiums for the 40-year-olds shown in the HHS examples (and raises them for older people not considered in the HHS presentation). As discussed below, it also assumes that states waive the ACA requirement that health plans cover a set of “Essential Health Benefits” (EHB), such as maternity care and mental health treatment, leading to lower premiums because plans cover less.

- At the same time, the HHS analysis ignores the Senate bill’s sharp cuts to tax credits to help low- and moderate-income people buy insurance and its repeal of cost sharing reduction subsidies. That assumption is crucial, because it means that large numbers of healthier-than-average, low- and moderate-income people would continue enrolling in ACA-compliant plans, since the HHS analysis assumes that the current, generous subsidies remain available. That would mitigate the damage of the Cruz amendment by limiting both the deterioration of the risk pool and the associated premium increases. By contrast, the Congressional Budget Office concluded that under the Senate bill (without the Cruz amendment), “few low-income people would purchase coverage” due to the bill’s large reductions in subsidies.[5] Without lower-income healthy people to hold the risk pool together, the premium increases under the Cruz amendment would likely be far higher, with far worse consequences for people with pre-existing conditions and with incomes that are too high for them to qualify for subsidies.

Moreover, HHS’s premium estimates for the Cruz amendment also assume that states would take the Senate bill’s option to waive EHB standards and insurers would respond by covering fewer benefits, likely excluding services like maternity coverage, mental health, and substance use treatment. Thus, an apples-to-apples comparison based on the HHS data would likely find that the Cruz amendment would leave people paying more for substantially worse coverage with large gaps in benefits.

HHS rules out some of the most troubling potential results of the Cruz amendment by assumption, not analysis. In a joint letter, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association and American’s Health Insurance Plans, the two major associations of health insurers, cautioned that the Cruz amendment could leave some consumers with no individual market options at all as insurers withdraw entirely from the market due to what’s known as “adverse selection” — with insurers choosing to cover healthier, less costly individuals rather than sicker, costlier ones. “[T]his provision,” they wrote, “will lead to far fewer, if any, coverage options for consumers who purchase their plan in the individual market. As a result, millions more individuals will become uninsured [emphasis added].”[6] By contrast, HHS notes that under its analysis, “it is assumed that an adequate number of insurers offer at least one bronze, silver, and gold qualified health plan.” In other words, the HHS analysis just assumes — without justification or modeling — that there would be sufficient competition to provide consumers with options; it doesn’t evaluate whether the Cruz amendment would actually leave some consumers without options.

Much of the HHS presentation is irrelevant to the Cruz amendment. The first half of the presentation purports to analyze the Cruz amendment but then ignores key aspects of it: for example, it appears to assume that non-ACA-compliant plans would not be allowed to charge higher premiums based on health status, even though that’s clearly inconsistent with the amendment’s purpose and text. As the American Academy of Actuaries and other experts have explained, the fact that the amendment retains the ACA’s “single risk pool” language does not change the reality that it re-introduces discrimination based on pre-existing conditions. [7]

HHS’s finding that non-ACA-compliant plans would have much lower premiums is driven by its finding that these plans would also offer minimal coverage. HHS’s analysis does find that non-ACA compliant plans would have substantially lower premiums than the comprehensive plans available under either current law or the Cruz amendment. That’s partly because of the market segmentation described above: non-ACA-compliant plans would enroll only healthier people, so they would naturally charge lower premiums. But it’s also because these plans would offer minimal financial protection:

- These plans, according to the HHS presentation, would have $12,000 deductibles. That compares to a median deductible of $3,000 in benchmark “silver plans” under current law and roughly $6,000 deductibles in the benchmark plans available under the Senate bill without the Cruz amendment.

- In addition, as noted, HHS assumes that states would take advantage of the Senate bill’s option to waive EHB standards. Thus, plans created under the Cruz amendment would likely exclude services like maternity care, mental health, and substance use treatment that were frequently excluded from coverage before the ACA.