The health policies in the President's fiscal year 2019 budget are a continuation of the Administration's health care agenda of the past year. Throughout 2017, the President pressed Congress to enact legislation repealing the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and making deep cuts to Medicaid. Meanwhile, the Administration is using waivers and regulatory changes to implement (and allow states to implement) policies that make it harder for eligible people to get health coverage and care. The budget doubles down in both of these areas. It embraces the ACA repeal-and-replace bill sponsored by Senators Bill Cassidy, Lindsey Graham, Dean Heller, and Ron Johnson (the "Cassidy-Graham" proposal), then proposes to cut funding for coverage programs deeply below the levels in that bill. It also includes additional proposals designed to make it harder for low- and moderate-income people to enroll in Medicaid coverage and marketplace subsidies, even while these programs remain available in their current form. In total, the budget cuts Medicaid and ACA marketplace subsidies by $763 billion over ten years, with the cuts growing steeply over time.

Outside of these areas, some of the health proposals in the budget have merit and deserve further consideration — for example, a number of its Medicare payment reforms. But even in the areas where the budget puts forward a more positive agenda, such as behavioral health and prescription drugs policy, aspects of its proposals raise concerns.

Affordable Care Act Repeal and Medicaid Overhaul

The budget embraces the Cassidy-Graham ACA repeal-and-replace bill, then proposes to cut coverage funding deeply below the levels in the bill.[2] Specifically:

- The budget would completely eliminate the ACA's Medicaid expansion, which has extended coverage to 12 million low-income adults, as well as its marketplace subsidies, which help more than 8 million people afford coverage. The budget wipes out these programs and demands that states come up with alternatives in less than two years. The result, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), state insurance commissioners, and state Medicaid directors, would be massive disruption, given the scope of work, unrealistic timeline, and insufficient resources.[3]

- The budget would replace the ACA's major coverage expansions with a vastly inadequate block grant. After an initial increase, block grant funding levels would ultimately fall far below current-law funding for coverage programs, since the block grant would grow only with general inflation, with no adjustment for population growth or health care costs. (These cuts would come on top of the large reductions in federal funding for coverage resulting from the December tax bill's repeal of the ACA's individual mandate, the requirement that most people have health insurance or pay a penalty.) Block grant funding also would not adjust from year to year for unexpected costs, leaving states entirely on the hook for any and all such costs from recessions, natural disasters, public health emergencies, or prescription drug price spikes, making it even harder for states to use these funds to even partially replace ACA coverage programs. In analyzing the Cassidy-Graham legislation, CBO concluded that its block grant would not enable states to establish coverage programs comparable to those in place under current law. Instead, states that did not expand Medicaid would use block grant funds in part to supplant state funding for existing programs, while Medicaid expansion states would struggle to maintain coverage for low-income adults and would generally not be able to replace the ACA subsidies that make marketplace coverage affordable for moderate-income consumers.[4]

- The budget also would convert the rest of the Medicaid program, which covers seniors, people with disabilities, children, and pregnant women, to a per capita cap, limiting the amount of federal funding for each person enrolled in Medicaid regardless of need. The per capita cap amounts would increase only with general inflation, falling further and further below the cost of providing health care to vulnerable populations.

- The Cassidy-Graham bill the budget endorses also gives states broad authority to eliminate or weaken many of the ACA's protections for people with pre-existing conditions. Depending on how they used block grant dollars, states could permit insurers to charge higher premiums for people with pre-existing conditions or exclude key benefits from coverage for all individual market plans. As the CBO wrote in its preliminary analysis of the Cassidy-Graham plan, because the proposal would create such extreme disruption in insurance markets, states would face intense pressure to try to stabilize their markets by weakening these protections.

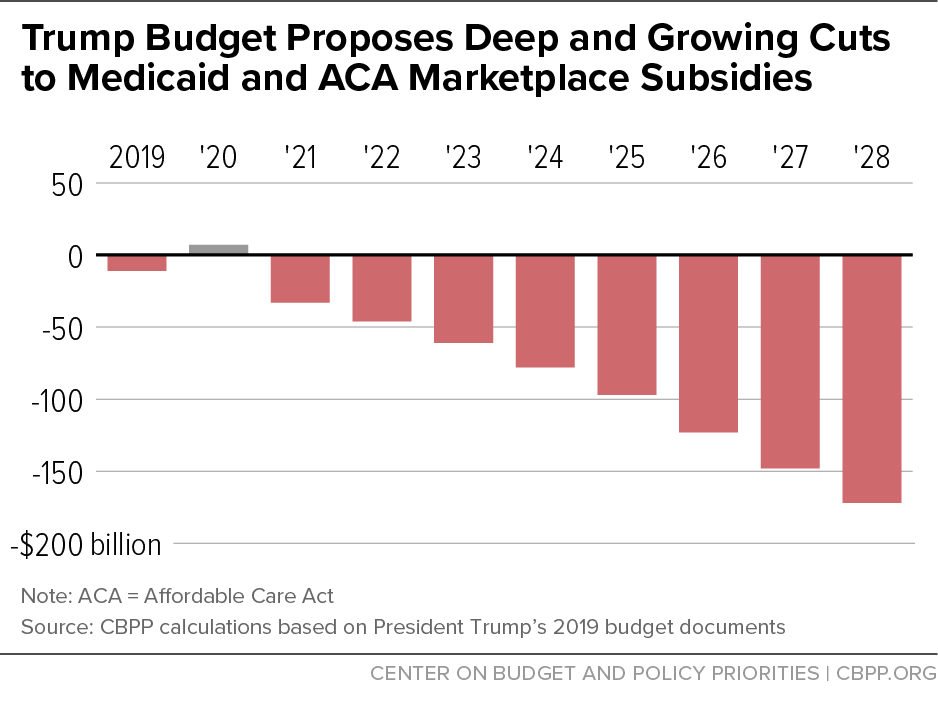

These proposals — in combination with other proposals in the budget (some discussed below) — would cut federal funding by a total of $763 billion over the ten-year period ending in 2028 (see Figure 1), compared to current-law funding for Medicaid expansion and subsidies, and by about $1.1 trillion relative to the baseline before the tax bill repealed the individual mandate.[5] The result would be millions losing coverage and worse or less affordable coverage for millions more. Experts concluded that the Cassidy-Graham proposal for Medicaid and the ACA used as the framework for the budget would — in combination with repeal of the individual mandate — likely lead to a total coverage loss of more than 20 million people, and the budget's proposed cuts to coverage are much deeper.[6]

Additional Eligibility Restrictions and Barriers to Coverage and Care

ACA repeal and a Medicaid per capita cap seem unlikely to be enacted during 2018. But the Administration has moved forward with administrative actions that advance some of the same goals on a smaller scale — for example, Medicaid waivers that will make it harder for low-income adults to obtain and maintain coverage and actions that discourage marketplace enrollment and make marketplace plans more expensive.[7] Separate from its proposals to repeal the ACA, the budget puts forward a number of Medicaid and marketplace policies in that same spirit.

Many lawfully present immigrants, as well as all undocumented immigrants, are ineligible for Medicaid based on their immigration status, and states are required to verify that applicants are either citizens or have an eligible immigration status as part of determining eligibility for the program. States have tools to verify the citizenship or immigration status of the vast majority of applicants very quickly using data matching with other government agencies, but in some cases the process takes longer. In these cases, current law requires states to issue Medicaid benefits to people who have attested under penalty of perjury that they are citizens or have an eligible immigration status and who meet other eligibility factors such as income. This policy helps avoid what could otherwise be long delays while people obtain the documents they need and the state Medicaid agency processes them.

The budget proposes to eliminate this "reasonable opportunity" period and prohibit federal funding for Medicaid coverage until citizenship or immigration status has been verified. For some eligible people — including children, pregnant women, people with disabilities, and elderly individuals — this may result in significant delays in obtaining needed health care.

Ironically, past experience in Medicaid shows that U.S. citizens — rather than Medicaid-eligible immigrants — would likely experience the greatest harm.[8] Immigrants generally must have documents that prove their immigration status, so when data matching can't immediately verify their status, they can more easily produce documents to satisfy the verification requirement. U.S. citizens are not required to carry documentation to prove their citizenship and often have a more difficult time producing documents like a birth certificate or record of birth abroad, and many U.S. citizens don't have passports. Examples of U.S. citizens who may be delayed in getting Medicaid under this policy include:

- Newborns: obtaining a birth certificate can take up to six weeks, longer if parents do not apply for a Social Security number at the hospital (for example because they have not yet chosen a name).

- Adult citizen applicants born abroad, who are often not able to have their citizenship verified through data matching and may not have proof of citizenship readily available.

- People who have changed their names (such as people newly married).

- Anyone else who has an error in their Social Security record.

The budget would allow states to consider assets such as retirement savings accounts and some vehicles in determining Medicaid eligibility for children, parents, pregnant women, and other adults, undoing a major simplification achieved through the ACA, which eliminated these tests. Asset tests generally had little impact on Medicaid eligibility: most people with incomes below the Medicaid limit don't have significant assets, so few people were found ineligible for Medicaid based on assets. But asset tests have a number of serious downsides.

First, having to document assets increases paperwork, deters some eligible people from applying for Medicaid, and leads to delays or even denials of coverage for eligible people — not because they have substantial assets but because they fail to provide all the paperwork proving they don't.

Second and related, asset tests increase administrative costs and burdens for states. Even before the ACA, many states dropped asset tests because they were costly to implement and so few people were found to have assets over the limit.[9]

Third, imposing asset tests would have the perverse effect of making some very low-income people ineligible for both Medicaid and marketplace premium tax credits, the problem the ACA intended to avoid by eliminating asset tests. With an asset test, some people could be ineligible for Medicaid because their assets are above the state's limit, but ineligible for premium tax credits because their income is too low.

Finally, asset tests can discourage low-income people from accumulating even modest savings (in some states, as little as $1,000) and punish them severely if they do.[10] Asset tests would be especially harmful for people who have contributed to retirement accounts but temporarily fall on hard times. These individuals would be forced to spend down their savings and incur associated penalties and fees in order to gain Medicaid eligibility for what may be a short window of time.

The President's budget proposes to eliminate states' existing flexibility to increase the amount of home equity seniors and people with disabilities may hold without losing eligibility for Medicaid. Current federal guidelines set a range: $572,000 to $858,000 in 2018.[11] A state using the minimum level, for example, would count home value exceeding $572,000 as an asset for purposes of determining Medicaid eligibility.[12] But a number of states, many of them states with higher-than-average home values, take advantage of the existing flexibility to set higher limits: California, Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, and Wisconsin.[13]

The President's budget would require all states to use the lower $572,000 minimum home equity limit.[14] This change would make it harder for seniors and people with disabilities in states whose home value limit exceeds that minimum amount to qualify for Medicaid. It could force people in these states to sell their homes and cause a delay in their care until their house is sold.

Under existing Medicaid state plan authority, states have considerable flexibility to establish cost-sharing amounts for beneficiaries, including imposing a maximum $8 copayment for non-emergency use of the emergency department (ED). But to impose a copayment that exceeds this $8 maximum, states need to obtain a special waiver under section 1916(f) of the Social Security Act. Only one state, Indiana, has ever received approval for such a waiver, which gave it the authority to impose a $25 copayment for non-emergency use of the ED after a beneficiary's first visit.

The President's budget proposes to allow states to amend their Medicaid state plans and impose higher copayments for non-emergency use of the ED. The Trump Administration claims that this will "encourage personal financial responsibility and proper use of health care resources." But this hypothesis has already been tested in Indiana and turns out to be false. Indiana's evaluation of its graduated copayment shows no difference in use of the ED for non-emergency visits between Medicaid beneficiaries with an $8 copayment and those with a $25 copayment.[15] An earlier study also found that copays for non-emergency use of the ED didn't change beneficiaries' use of the ED or primary care.[16] In light of that evidence, there is no justification for weakening beneficiary protections and imposing copayments that may deter appropriate use of the ED.

One important benefit provided by Medicaid coverage is transportation to health care appointments, referred to as non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT). Studies find that lack of transportation is an important obstacle to getting needed care for low-income people, especially for elderly people and those with disabilities or chronic conditions.[17] In 2015, Medicaid NEMT was most commonly used to access behavioral health care and was also frequently used to access dialysis and preventive care.[18]

The President's budget outlines the Administration's plan to take regulatory action to make Medicaid's NEMT benefit optional, despite evidence that eliminating NEMT worsens access to care.[19] To date, CMS has granted waivers of NEMT for non-disabled adults to three states — Indiana, Iowa, and Kentucky. A 2016 evaluation[20] of Indiana's waiver found that beneficiaries without access to NEMT were more likely to list transportation difficulties as a reason for missing an appointment than beneficiaries with access to the benefit. In addition, among beneficiaries without the NEMT benefit who missed an appointment, the proportion who identified transportation as a reason was nearly double among those with incomes below the poverty line compared to those with incomes above the poverty line.

Under current law, marketplace consumers who receive premium tax credits have three months to pay overdue premiums before insurers can end their coverage. The President's budget proposes reducing the premium payment grace period from three months to one month, meaning people who fall behind on their marketplace premiums would lose coverage more quickly and might remain uninsured until the next enrollment period.[21]

As CBO explained in scoring a similar provision, the proposal's savings would come not from those whose coverage is terminated due to their failure to pay their premiums, but rather from lost premium tax credits for people "who would have paid their delinquent premiums during the second or third month of their grace period [but] would instead have their coverage terminated."[22] That's because people who fail to pay premiums within 90 days already lose coverage and financial assistance for the second and third months of the grace period (the federal government doesn't pay their premium tax credits, and insurers don't have to pay their claims). The savings from the proposal would come from taking coverage and financial assistance away from people who would catch up on premiums within 90 days but can't in just 30. Based on state data on grace period use, we estimated that a similar congressional proposal would cause between 259,000 and 688,000 people per year to lose coverage.[23]

Substance Use and Mental Health Funding and Policies

The budget provides $13 billion in new funding to address the opioid epidemic and improve services for people with serious mental illness. Yet at the same time, it continues efforts to repeal the Medicaid expansion and make deep cuts in Medicaid that would affect those remaining in the program. Medicaid is fundamental to addressing the opioid epidemic and substance use disorders, and expansion has significantly increased health coverage and access to treatment for substance use disorders and mental illness. [24] The budget's proposed Medicaid changes would far outweigh any positive impact that could be gained through grant funding or other investments.

The budget does include several promising approaches to addressing the opioid epidemic, including:

- $1 billion for state grants to increase the availability of opioid treatment. This would double a program authorized under the 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 that gives each state and U.S. territory funding based on the rate of overdose deaths and unmet need for opioid use disorder treatment.

- A requirement that state Medicaid programs cover all medication-assisted treatment (MAT) options approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

- Targeted resources for American Indian and Alaska Native communities, people living in rural areas with high opioid death rates, and pregnant women, as well as first responder training and drug courts, which help people with non-violent offenses avoid jail if they engage in treatment.

While these initiatives would be helpful, a longer-term approach is needed with resources beyond the one year addressed in the budget. Moreover, the budget provides no details on how the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) would use most of the $13 billion in funds. There should be a transparent plan and process for distributing these funds to ensure maximum impact and coordination with existing initiatives.

Experts have estimated that as much as $60 billion over ten years is needed to address the opioid epidemic, assuming no cuts in Medicaid.[25] Moreover, the budget's focus solely on the opioid epidemic ignores the need to address other substance use disorders. For example, there are several MAT options for people with alcohol use disorders, but they are not included in the proposal to require states to cover MAT for opioid use.[26] And the budget's deep cuts to non-defense discretionary funding in later years — an 18 percent cut by 2020 compared to 2017 levels, adjusted for inflation, growing to 42 percent by 2028 — would inevitably lead to cuts to programs that help address substance use and mental health.

In rolling out the budget, the Administration highlighted its proposals to address prescription drug costs. Of the proposed changes to Medicare and Medicaid policy, some are promising and deserve further consideration. For example, eliminating copayments for generic drugs for low-income Medicare beneficiaries could improve access to care and promote medication adherence. Other proposals, however, could end up limiting access to needed care.

The budget proposes to allow up to five states to limit access to prescription drugs in their Medicaid programs. This proposal risks causing harm to vulnerable Medicaid enrollees and would likely have a limited effect on Medicaid drug costs.

Under current law, the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) does not have the authority to allow states to refuse to cover specific drugs, an approach known as a closed drug formulary. Medicaid law requires states that include prescription drug coverage in their Medicaid programs — which all states do — to cover all FDA-approved drugs (with limited exceptions, defined in the law). However, states do have tools that allow them to negotiate better deals with drug manufacturers and to limit enrollees' access to specialized, high-cost drugs in order to ensure they are used efficiently. They can require prior authorization in order to get a specialized medication or require Medicaid beneficiaries to try a lower-cost drug within a class before getting a high-cost one.

In return for covering all prescription drugs, Medicaid requires drug companies to provide substantial rebates, giving states a much lower price than typically offered to commercial health plans. These provisions of law — requiring coverage of all FDA-approved products and requiring drug manufacturers to provide states with rebates — reflect a carefully negotiated legislative compromise that has led to significant cost savings for state Medicaid agencies: the rebates allow the federal government and the states to achieve savings of about 50 percent, according to analysis from the HHS Office of Inspector General.[27]

The President's budget proposes to change the law to give CMS authority to pilot closed formularies in up to five states, estimating that the pilots will save the federal government $85 million over a ten-year period. The goal of the proposal is to give the pilot states "more flexibility" in negotiating prices with manufacturers, "rather than participating in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program." However, states already negotiate drug prices with drug companies today (in addition to participating in the federal rebate program). As noted, they are already able to give certain drugs preferred status in order to negotiate better deals. It's unlikely that states could achieve substantially more in savings than they currently receive through the combination of the federal rebate program and supplemental rebates — and some may save significantly less.

Meanwhile, creating a closed formulary could prevent some Medicaid beneficiaries from getting the medications they need. While the proposal does include an appeals process to protect Medicaid beneficiaries' access, this structure would impose a considerable burden on beneficiaries who need drugs that are not covered, which would very likely lead to some people going without needed care. Medicaid beneficiaries tend to be more frail than the general population, and barriers such as lengthy appeals processes could significantly reduce access to needed care.

Perhaps in recognition of these risks, the President's budget does structure this proposal as a pilot program and requires a rigorous evaluation, which is critical when considering any new policy with the potential to harm beneficiaries. However, in this case, the likelihood of harm and the risk of disrupting the rebate program make this policy a poor candidate for a demonstration. Moreover, an evaluation might not capture the full effects of this proposal. In particular, a limited pilot program likely cannot evaluate the risk that closed formularies undermine the drug rebate program. If that occurred, it could significantly increase Medicaid drug costs for states and the federal government over time.

Proposed changes in the Medicare Part D drug benefit would reduce out-of-pocket costs for some beneficiaries, including those with the highest spending, but increase costs for others. The budget would place a limit on out-of-pocket drug spending, allow beneficiaries to share directly in manufacturers' rebates, and eliminate cost-sharing on generic drugs for low-income beneficiaries. It would pay for these improvements by charging more to beneficiaries whose drug spending is high, but below the catastrophic limit.

Another proposal would loosen Part D plan formulary standards to require a minimum of one drug per category or class rather than two, as is now the case. The proposal would also allow Part D plans to implement a broader range of controls on specialty drugs and drugs in protected classes. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has recommended giving plans limited additional flexibility to use formulary tools, but retaining most beneficiary protections, including requiring coverage of at least two drugs per therapeutic class.[28]

The fiscal year 2019 budget proposes $554 billion in net Medicare spending reductions over the next ten years. According to the Administration these changes would extend the life of Medicare's Hospital Insurance trust fund by eight years (from 2029 to 2037). Almost all of the proposals would reduce payments to health care providers, and few would directly affect Medicare beneficiaries.

The proposals include establishing a new payment system for post-acute care, extending the 2 percent mandatory sequestration through 2028, reducing Medicare coverage of bad debts, and paying for all physician services at the same rate, regardless of whether they are provided in a doctor's office or other setting. In two instances — payments to hospitals for graduate medical education and for uncompensated care — the budget proposes to move spending out of the Medicare trust funds into new, smaller grant programs funded by general revenues. Several of these proposals — such as site-neutral physician payments — are similar to recommendations from MedPAC.[29]

The budget also proposes to give Medicare beneficiaries with high-deductible health plans the option to make tax-deductible contributions to Medical Savings Accounts or Health Savings Accounts. This proposal would raise Medicare costs slightly and reduce tax revenues by $11 billion over ten years. It would largely represent an additional tax break for high-income taxpayers, who face the highest marginal income tax rates and have the greatest capacity to make contributions to savings accounts.