The 2.2 million uninsured adults with incomes below the poverty line who were caught in the Medicaid “coverage gap” in 2019 are a varied group — they’re essential workers, parents caring for children, older and younger adults, and diverse in terms of race and ethnicity — but they all have something in common. They live in states that have failed to adopt the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion, even with significant federal financial incentives, leaving this group with no pathway to affordable coverage.

States that haven’t implemented expansion should do so, and to account for states that won’t, Congress should act on calls from Senators Warnock and Ossoff and over 60 civil rights and other organizations to close the coverage gap by creating a federal fallback.[1]

Adults in the coverage gap have incomes below the poverty line, which is too low to qualify for subsidized health insurance coverage in the ACA marketplaces, yet they don’t qualify for Medicaid under their states’ rules.[2] As enacted, the ACA extended Medicaid coverage to adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the poverty line, with subsidized marketplace coverage available to those with higher incomes.[3] However, the Supreme Court allowed states to choose whether to expand Medicaid, creating a coverage gap for people with incomes below the poverty line in the 12 states that haven’t expanded. These states’ income eligibility rules for Medicaid are stringent; the median state caps eligibility for parents at about 40 percent of the federal poverty line, or just $8,800 in yearly income for a single caregiver of two children. Generally, adults without children are ineligible for Medicaid in these states, regardless of how low their incomes are.[4]

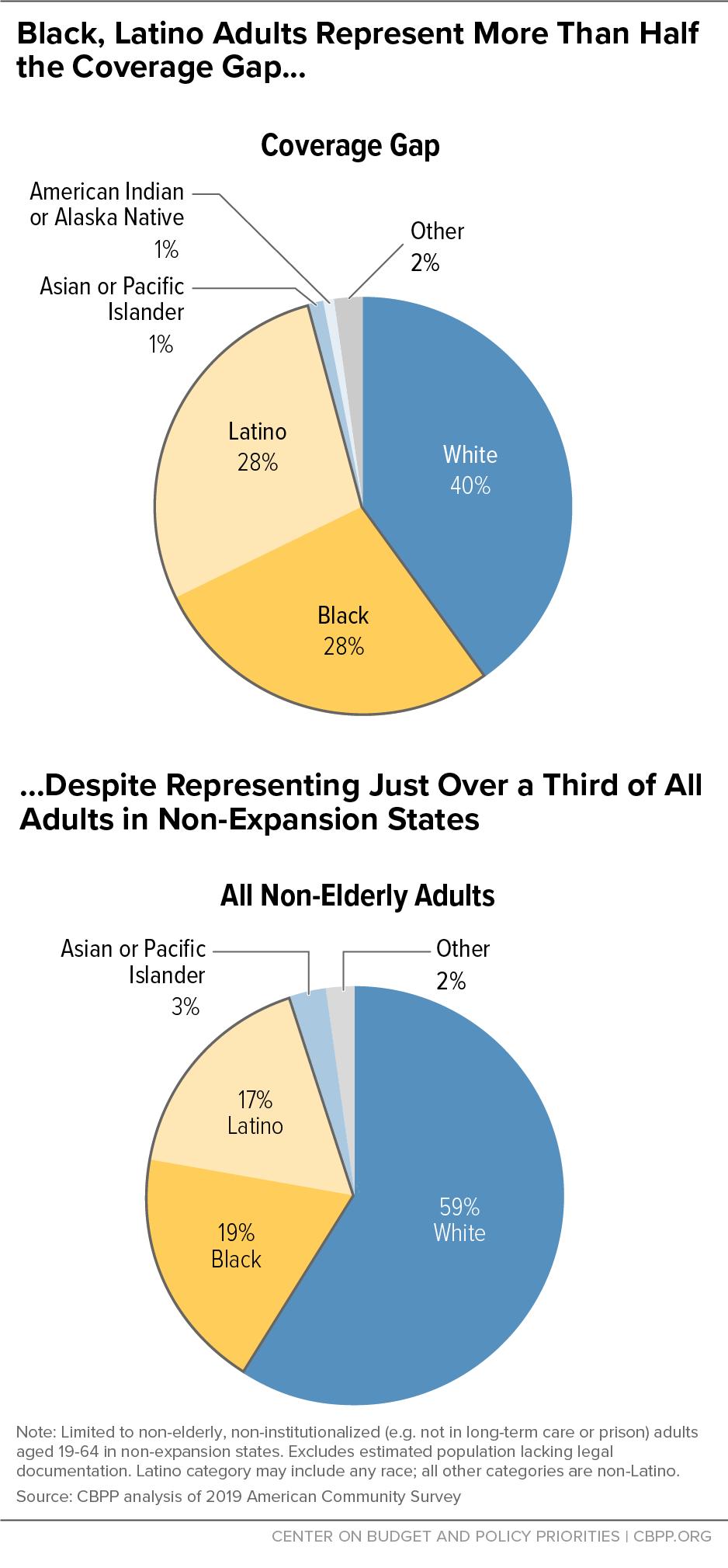

Extending health insurance to people in the coverage gap squarely benefits people with incomes below the poverty line who are uninsured and lack any access to affordable coverage. Some 60 percent of people in the gap in 2019 were people of color, reflecting long-standing racial and ethnic disparities in health care access that coverage extensions would do much to address.

And it would improve health care access for people who are in the coverage gap because of their employment challenges and caregiving responsibilities. Half of the coverage gap population worked in 2019, but much of the population experiences structural barriers to finding consistent work; their jobs are disproportionately less likely to offer health insurance; and their incomes fluctuate, which can put parents (who qualify for Medicaid in non-expansion states if their incomes are very low) into and out of eligibility. One in 3 people in the gap were parents with children at home. Research shows that extending coverage to parents increases enrollment among eligible children, so closing the coverage gap for adults would lead to coverage gains for children as well.

We estimate that 2.2 million adults aged 19 to 64 fell in the coverage gap in 2019 among the 12 non-expansion states. Our estimates are based on the 2019 American Community Survey, the most recent year of this survey available, and all estimates unless otherwise noted are for 2019. These data were collected prior to the pandemic and accompanying recession, and it is likely that accounting for job and income losses during the pandemic would lead to a larger estimate of the population in the coverage gap.

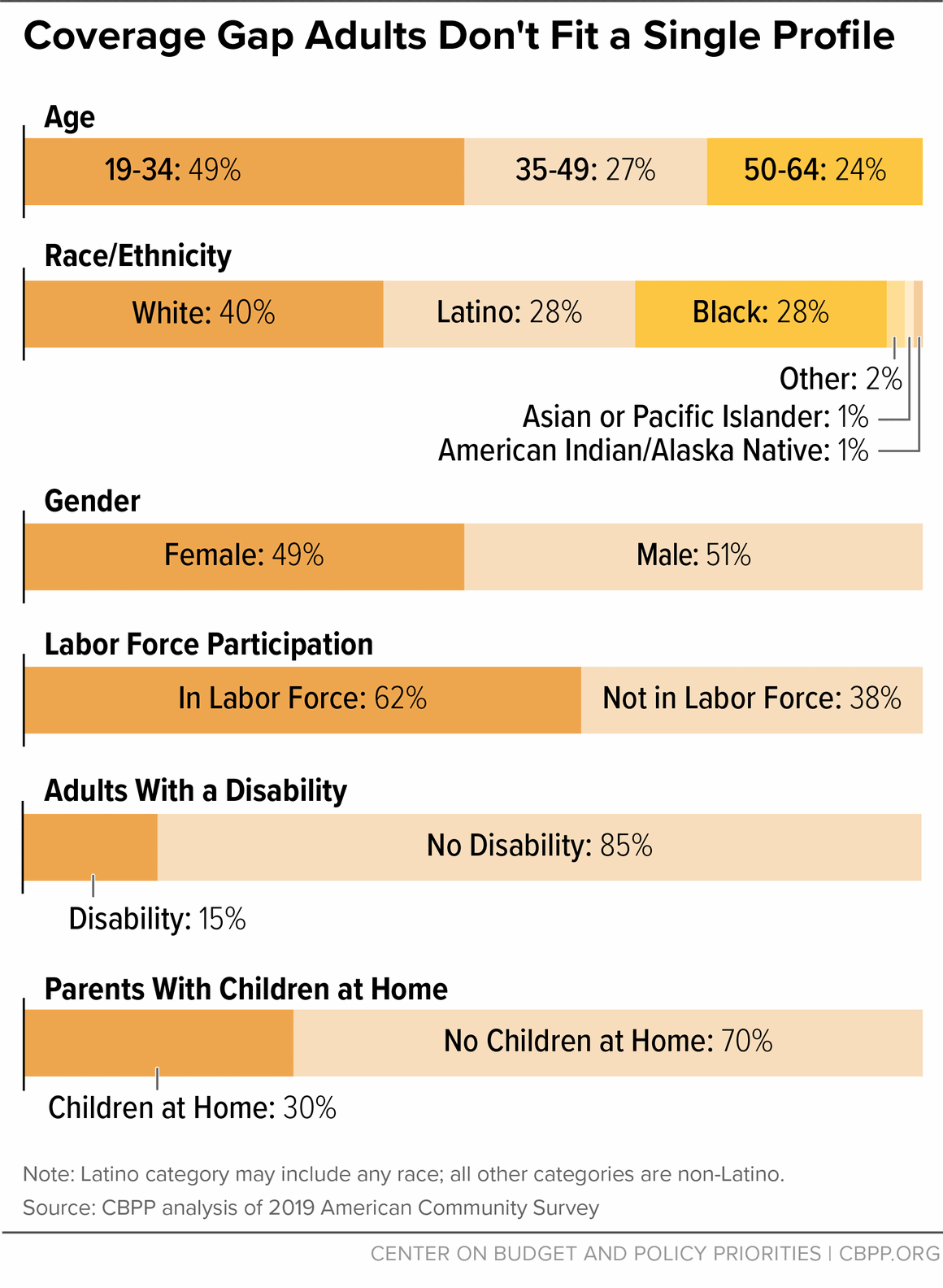

Across the 12 non-expansion states, those in the coverage gap were split almost evenly between women and men, and they spanned the 19-to-64 age spectrum of adults covered under expansion. About half of adults in the coverage gap were over 35, including about a quarter who were 50 to 64. (See Appendix I, Table 1, and Appendix II for our methodology.) Among those who were middle-aged and older, women comprised a slight majority, while most of those aged 19 to 34 were men.

Those in the coverage gap were disproportionately people of color. Most were in the labor force, roughly half were employed, and 1 in 3 were parents with children at home. Over half a million workers in the coverage gap were employed in front-line or essential industries, and about 15 percent of adults had a disability.

While we estimate that 2.2 million adults fell in the coverage gap in 2019, fluctuations in income and other eligibility criteria mean that many more people find themselves in the coverage gap over the course of a year. One study found that in a one-year period, low- and moderate-income households typically experienced more than five months in which their income fluctuated by more than 25 percent above or below their monthly average.[5] Transitions into and out of Medicaid coverage are also frequent. For example, 13 percent of non-elderly adults with Medicaid coverage in January 2018 had lost coverage and become uninsured at least once by the end of the year.[6]

Coverage Gap Exacerbates Racial and Ethnic Disparities

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted and exacerbated long-standing racial, economic, and health system inequities. People of color are disproportionately likely to lack access to care and have faced higher risks for COVID infection, hospitalization, and death.[7] The ACA helped reduce disparities in health insurance coverage among states that expanded, but the coverage gap worsens these disparities by disproportionately denying coverage to people of color.[8] While people of color comprised 41 percent of the adult, non-elderly population in non-expansion states, they made up 60 percent of people in the coverage gap, including 28 percent who are Latino and 28 percent who are Black.[9] (See Figure 1.)

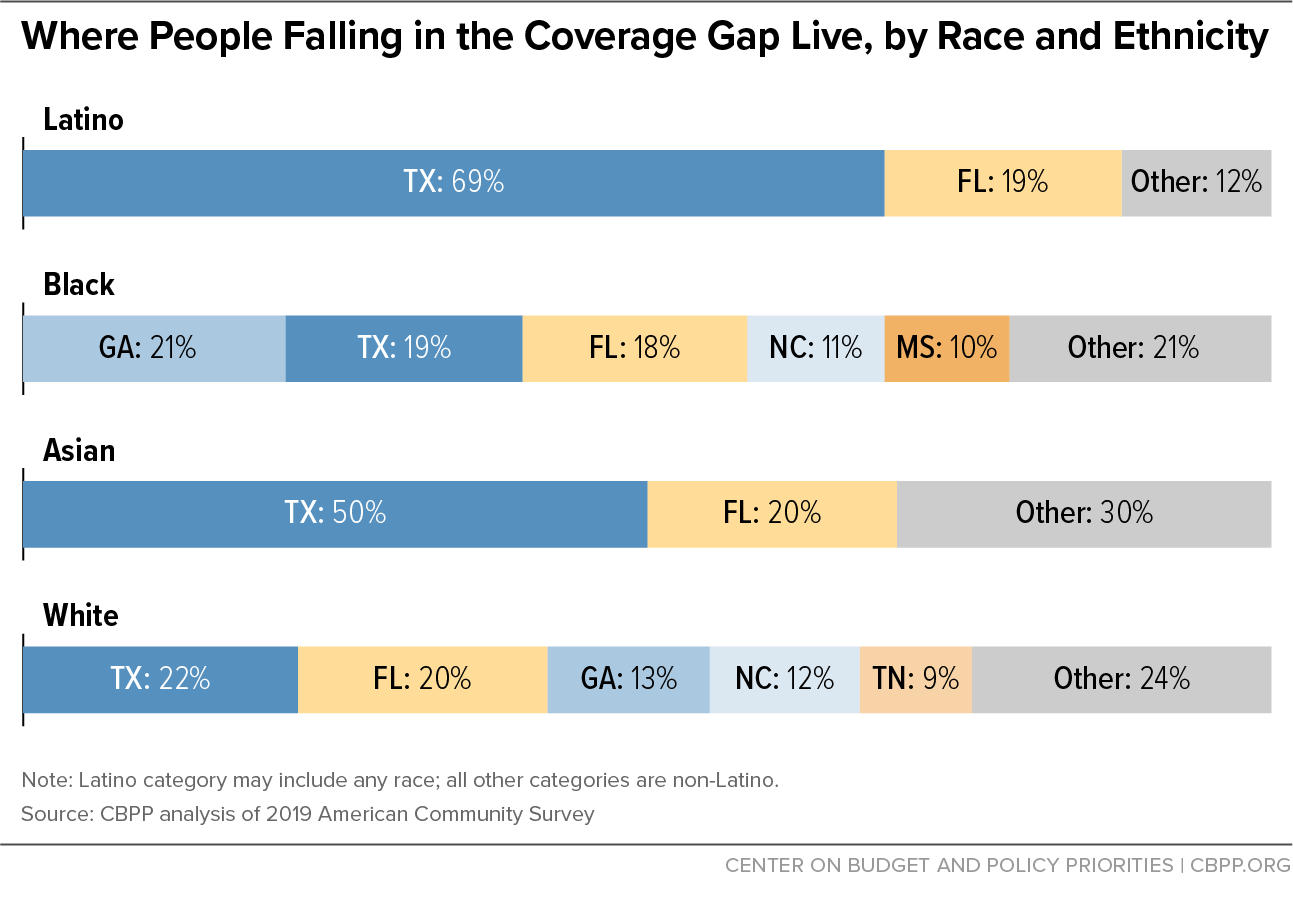

The vast majority of people in the coverage gap in 2019 lived in Southern states, with variations in racial and ethnic distributions. In Texas people of color made up 74 percent of those in the coverage gap, with Latino adults alone comprising 55 percent. In Mississippi most of the coverage gap population was Black, and in both Georgia and South Carolina it was more than 40 percent Black. (See Figure 2 and Appendix I, Table 2.) Over 70 percent of Asian adults and 88 percent of Latino adults in the coverage gap lived in Texas and Florida.

Most adults in the coverage gap work or have caregiving responsibilities. Though by definition all adults in the coverage gap have incomes below the poverty line, 62 percent were in the labor force (that is, either working or available and actively looking for work) and about half — well over 1 million people — were employed in 2019. (See Figure 3 and Appendix I, Table 4.) In addition to facing inconsistent work opportunities as noted above, many in this group worked in low-wage jobs, which have accounted for a disproportionate share of the job losses due to the pandemic and downturn. Medicaid expansion, meanwhile, has been shown to improve people’s employment prospects.[10]

Approximately 3 in 10 adults in the coverage gap were parents with children at home, and about one-third of these parents had a child under the age of 5. (See Figure 3 and Appendix I, Table 5.) The pandemic’s strain on caregivers and in turn on their children has been alarmingly high, making affordable health coverage key for both these groups.[11]

More than a third of all adults in the coverage gap were women of reproductive age (See Appendix I, Table 5). If they become pregnant, these women can apply for pregnancy coverage. But coverage wouldn’t start until they’re determined eligible for Medicaid, which means they wouldn’t be covered before they became pregnant and during the first months of pregnancy and could miss out on services like preconception health counseling and early prenatal care. An Oregon study found that Medicaid expansion was associated with an increase in early and adequate prenatal care.[12]

Medicaid expansion also provides an important pathway to coverage for people with disabilities. Nearly a quarter of non-elderly adult Medicaid enrollees had a disability, and most of them did not qualify for Medicaid through a disability pathway such as receipt of Supplemental Security Income (SSI). That’s because many people with a disability don’t meet strict state or federal standards for disability. Instead, most Medicaid enrollees with disabilities are eligible based on their income; for many this eligibility depends on their state’s Medicaid expansion decision.[13] We estimate that there were approximately 324,000 uninsured adults in the coverage gap who had disabilities in 2019, or roughly 15 percent of the total coverage gap population. (See Appendix I, Table 6.) Among them, 7 percent had a serious cognitive difficulty, and more than 6 percent had difficulty with basic physical activities such as walking, climbing stairs, carrying, or reaching.

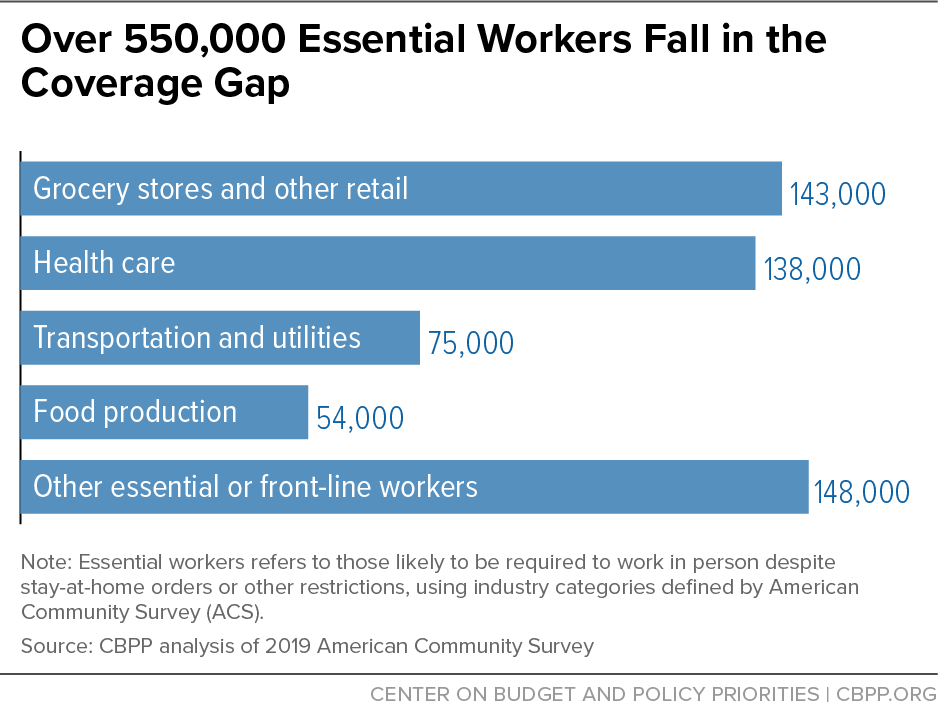

During the COVID-19 pandemic, even as millions of people work in jobs that allow them to stay at home, millions of other front-line or essential people went to work (and continue to go to work) in person as health care workers, bus drivers, grocery store workers, food production workers, and other jobs that people rely on. Expansion states cut the uninsured rate for these workers by half from 2013 to 2019, double the reduction in non-expansion states, making these states better prepared for the pandemic and economic downturn.[14]

Over 550,000 essential workers fell in the coverage gap in 2019. When the pandemic hit, such workers were left with no access to affordable coverage even as they risked their safety providing essential goods and services. Among those in the gap in 2019, 138,000 were health care workers and 143,000 were employed at grocery stores and in other front-line retail industries.[15] They were concentrated in the largest coverage gap states, with 209,000 in Texas and 98,000 in Florida. (See Figure 4 and Appendix I, Table 3.) The industry distribution of these workers varied across states, with health care workers comprising the largest group in Texas and grocery store and other front-line retail workers making up pluralities in Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina.

A large body of research demonstrates that Medicaid expansion increases health insurance coverage, improves access to care, provides financial security, and improves health outcomes.

Medicaid Expansion Improves Coverage and Access to Care

States that expanded Medicaid have seen significantly greater reductions in uninsured rates than states that failed to expand. In 2019 the uninsured rate among low-income, non-elderly adults had fallen to roughly half of the pre-ACA rate in expansion states, from 35 percent in 2013 to 17 percent in 2019.[16] Non-expansion states experienced a much smaller reduction in the uninsured rate among this group, falling from 43 percent in 2013 to 34 percent in 2019. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that if the 12 remaining non-expansion states expand Medicaid, 4 million uninsured adults would become eligible for Medicaid coverage, equivalent to 36 percent of the uninsured non-elderly adult population in these states.[17]

Medicaid expansion affects children’s levels of health coverage. Research shows that extending coverage to parents increases enrollment among eligible children. As states implemented the ACA’s Medicaid expansions, more than 700,000 children gained coverage from 2013 to 2015.[18] Medicaid expansion results in higher utilization of well-child visits, which links children to needed care.[19] Young children without access to primary care may not have a pediatrician to track developmental milestones in growth or in walking and talking. Children enrolled in Medicaid benefit from greater access to dental care, eyeglasses, immunizations, asthma care, and pediatric check-ups as compared to uninsured children.[20] Proper healthcare in childhood improves health outcomes as children reach adulthood and beyond.[21]

People in the coverage gap are at greater risk of preventable premature deaths. Medicaid expansion increases the use of preventative care and significantly reduces the utilization of emergency care, which results in earlier detection of cancers and more effective treatment of chronic illnesses. A recent study published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics found that Medicaid expansion saved the lives of at least 19,200 adults aged 55 to 64 between 2014 and 2017. Conversely, 15,600 older adults died prematurely as a result of some states’ decisions not to expand.[22] This study examined only the first three years of expansion and found that the impact of expansion on mortality increased each year. Moreover, the study only examined the impact of premature deaths on older adults, not on the full population. The time since expansion has more than doubled since the study period, so the number of lives saved by expansion today is likely far greater.

Those in the coverage gap are also more susceptible to medical bankruptcy. Medicaid expansion is a powerful tool against financial hardship and bankruptcy as it protects beneficiaries from catastrophic out-of-pocket medical costs. In its first two years, Medicaid expansion led to a $3.4 billion reduction in medical debt sent to collections and 50,000 fewer bankruptcies nationwide.[23] Charity care and bad debt among hospitals fell by $8.6 billion (23 percent) from 2013 to 2015, with declines among states that expanded Medicaid several times larger than for those that did not.[24]

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 |

| State |

Total |

Female |

Male |

19 to 34 |

35 to 49 |

50 to 64 |

| Total, non-expansion states |

2,211,000 |

1,091,000 |

1,120,000 |

1,082,000 |

591,000 |

539,000 |

| Alabama |

137,000 |

68,000 |

69,000 |

65,000 |

40,000 |

32,000 |

| Florida |

425,000 |

193,000 |

231,000 |

190,000 |

109,000 |

126,000 |

| Georgia |

275,000 |

136,000 |

139,000 |

136,000 |

73,000 |

66,000 |

| Kansas |

44,000 |

23,000 |

21,000 |

23,000 |

10,000 |

11,000 |

| Mississippi |

110,000 |

55,000 |

55,000 |

55,000 |

30,000 |

25,000 |

| North Carolina |

207,000 |

98,000 |

109,000 |

99,000 |

58,000 |

50,000 |

| South Carolina |

105,000 |

52,000 |

53,000 |

43,000 |

29,000 |

34,000 |

| South Dakota |

16,000 |

7,000 |

9,000 |

8,000 |

* |

5,000 |

| Tennessee |

119,000 |

50,000 |

69,000 |

47,000 |

31,000 |

41,000 |

| Texas |

766,000 |

406,000 |

361,000 |

412,000 |

207,000 |

147,000 |

| Wyoming |

7,000 |

3,000 |

5,000 |

4,000 |

* |

* |

| APPENDIX TABLE 2 |

| State |

Total |

Asian |

Black |

Latino |

Other |

White |

| Total, non-expansion states |

2,211,000 |

29,000 |

617,000 |

613,000 |

60,000 |

893,000 |

| Alabama |

137,000 |

* |

53,000 |

* |

* |

75,000 |

| Florida |

425,000 |

6,000 |

109,000 |

118,000 |

12,000 |

179,000 |

| Georgia |

275,000 |

* |

130,000 |

24,000 |

* |

114,000 |

| Kansas |

44,000 |

* |

* |

8,000 |

4,000 |

26,000 |

| Mississippi |

110,000 |

* |

59,000 |

* |

* |

44,000 |

| North Carolina |

207,000 |

* |

68,000 |

19,000 |

12,000 |

106,000 |

| South Carolina |

105,000 |

* |

42,000 |

* |

* |

55,000 |

| South Dakota |

16,000 |

* |

* |

* |

6,000 |

9,000 |

| Tennessee |

119,000 |

* |

31,000 |

5,000 |

* |

79,000 |

| Texas |

766,000 |

14,000 |

118,000 |

422,000 |

12,000 |

200,000 |

| Wyoming |

7,000 |

* |

* |

* |

* |

5,000 |

| APPENDIX TABLE 3 |

| State |

|

| Total, non-expansion states |

558,000 |

| Alabama |

33,000 |

| Florida |

98,000 |

| Georgia |

67,000 |

| Kansas |

12,000 |

| Mississippi |

26,000 |

| North Carolina |

55,000 |

| South Carolina |

23,000 |

| South Dakota |

* |

| Tennessee |

28,000 |

| Texas |

209,000 |

| Wyoming |

* |

| APPENDIX TABLE 4 |

| State |

Adults in labor force |

Adults working |

| Total, non-expansion states |

1,362,000 |

1,073,000 |

| Alabama |

79,000 |

60,000 |

| Florida |

266,000 |

205,000 |

| Georgia |

165,000 |

125,000 |

| Kansas |

27,000 |

21,000 |

| Mississippi |

63,000 |

48,000 |

| North Carolina |

129,000 |

99,000 |

| South Carolina |

59,000 |

45,000 |

| South Dakota |

9,000 |

7,000 |

| Tennessee |

62,000 |

45,000 |

| Texas |

498,000 |

414,000 |

| Wyoming |

5,000 |

* |

| APPENDIX TABLE 5 |

| State |

Parents with children at home |

Women of reproductive age |

| Total, non-expansion states |

660,000 |

810,000 |

| Alabama |

40,000 |

51,000 |

| Florida |

108,000 |

130,000 |

| Georgia |

72,000 |

100,000 |

| Kansas |

13,000 |

17,000 |

| Mississippi |

31,000 |

43,000 |

| North Carolina |

61,000 |

73,000 |

| South Carolina |

21,000 |

34,000 |

| South Dakota |

* |

* |

| Tennessee |

11,000 |

31,000 |

| Texas |

297,000 |

324,000 |

| Wyoming |

* |

* |

| APPENDIX TABLE 6 |

| State |

|

| Total, non-expansion states |

324,000 |

| Alabama |

25,000 |

| Florida |

54,000 |

| Georgia |

40,000 |

| Kansas |

10,000 |

| Mississippi |

16,000 |

| North Carolina |

31,000 |

| South Carolina |

20,000 |

| South Dakota |

* |

| Tennessee |

27,000 |

| Texas |

96,000 |

| Wyoming |

* |

Appendix II: Data and Methods

We use the 2019 American Community Survey (ACS) from the Census Bureau, combined with state Medicaid eligibility rules, to estimate the coverage gap population in the remaining 12 states that have not enacted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion.[25] We define the coverage gap population as uninsured adults ages 19-64 whose incomes are below the poverty line and who are ineligible for Medicaid because the state did not adopt the expansion. This includes parents whose incomes are above the eligibility limits for parents with children and childless adults who wouldn’t be eligible at any income level.

Medicaid and the marketplace have different rules for defining income and family units for the purposes of gaining coverage. These categories of income and family units (known as “health insurance units” or HIUs) are not directly available in the ACS data and must be estimated, and we employ strategies broadly similar to those used by organizations such as the Kaiser Family Foundation. To assess income eligibility, we group individuals into two types of HIUs: Medicaid HIUs and marketplace HIUs. For each type of HIU, we apply each program’s rules for counting modified adjusted gross income for the purposes of eligibility. Our methodology for grouping into HIUs and counting income are based on ACS data and assumptions regarding family relationships, household composition, and tax filing rules and behavior.

We do not include populations in our coverage gap estimates that are already eligible for Medicaid or would not be eligible even if their states expanded. For example, we impute undocumented status and do not include the estimated population lacking legal documentation in our coverage gap estimates because under existing rules this group would not gain Medicaid eligibility if their states adopted the expansion.

We use industry definitions in the ACS to categorize adults who work in essential or front-line industries, including front-line health care services, essential transportation, essential utilities, essential warehousing, essential food production, essential manufacturing, front-line retail, essential public services, and other front-line services.

We define people as having a disability if they meet at least one of the six categories as defined by the Census Bureau: blind or with serious difficulty seeing; deaf or with serious difficulty hearing; serious cognitive difficulty; ambulatory difficulty (difficulty with a basic physical activity such as walking or reaching); difficulty with self-care such as dressing or bathing; or difficulty doing basic activities outside the home alone.