WIC ― the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children ― serves low-income pregnant and postpartum women, infants, and children up to age 5 who are at nutritional risk and plays a crucial role in improving their lifetime health. WIC effectively and efficiently provides nutritious foods, nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and referrals to health care and social services to millions of families.[2] Yet there is room to modernize and simplify enrollment to reach more eligible low-income families.

Despite the well-documented short- and long-term benefits of participating in WIC, both caseloads and the share of eligible families that enroll have declined in recent years. From WIC’s establishment in 1974 until 1997, the program did not receive enough annual funding to serve all eligible applicants, so staff had to prioritize applicants and manage waiting lists. Beginning in 1997, Congress and the Administration committed to fully serving all eligible applicants and WIC focused on expanding to reach eligible low-income families. Caseloads continued growing into the early 2000s and the Great Recession brought further increases; caseloads peaked in August 2009. The period of caseload declines since then is thus the first in WIC’s history and poses a new challenge for the program.[3] Moreover, WIC participation among eligible families has fallen since 2011. State and local WIC agencies have begun exploring how to make WIC easier to continue participating in as mothers return to work (babies tend to drop off the program as they become toddlers and preschoolers) and more accessible to eligible families generally.

One of WIC’s hallmarks is that it provides not only food assistance but also nutrition education and services; this interaction between staff and families fosters strong relationships and a customer-service orientation among WIC staff but means that participating in WIC takes more time, which can be extremely scarce for low-income mothers with young children. It is quite common for WIC participants to have four or more appointments each year, which can last anywhere from 45 minutes to a few hours depending on wait times and the complexity of the family’s circumstances. Moreover, shopping for WIC foods, which provide an average of about $62 monthly for each participant, can be difficult and embarrassing if the transaction is time-consuming and draws attention. These factors lead some eligible families to decline to enroll or drop out.

WIC programs around the country have been exploring ways to reduce the time families spend on paperwork, provide services in more flexible ways, and improve participants’ experience with buying WIC-approved groceries. This report focuses on efforts to streamline and modernize the enrollment process prior to waivers related to operations during COVID-19.

Some certification streamlining practices, such as appointment reminders or reviews of electronic documents during appointments, are widespread but not universal. More innovative practices, such as online appointment scheduling or electronic submission of documents before or after appointments, are much less common and WIC agencies are learning how to implement them effectively. In some instances, technology is central to streamlining efforts; for example, mobile phone apps and web portals now allow participants to find a WIC clinic or WIC-authorized store, update their contact information, or check whether a particular food is approved.[4] But business processes are just as important as technology to streamlining. For example, to make full use of the availability of electronic documents, staff must routinely ask participants about them, and applicants must be told before appointments that they can share information available online or a photo of a document.

During 2015 and 2016, in cooperation with the National WIC Association, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities gathered information on WIC practices and procedures that simplify applying for and maintaining WIC eligibility.[5] Since 2017, we have provided technical assistance to state and local WIC agencies seeking to implement these practices.[6] Over the course of a year, these agencies designed, implemented, and assessed a certification streamlining action plan.

This report explains why streamlining the certification process is important and describes opportunities for state and local policies to better support streamlining. Streamlining could free up staff time to devote to providing WIC’s core services and make it easier for eligible families to enroll in WIC and continue receiving benefits as their babies become toddlers. The report is built around 12 case studies of streamlining measures that agencies adopted, including their outcomes and the lessons they learned; those case studies offer concrete examples of steps that other state and local agencies can take.

Extensive research over four decades has found that participating in WIC improves low-income families’ nutrition and health:[7]

- Women who participate in WIC while pregnant give birth to healthier babies who are more likely to survive infancy.

- WIC supports more nutritious diets and better infant feeding practices. WIC participants buy and eat more fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy products, following the 2009 introduction of WIC food packages that are more closely aligned to current dietary guidance.

- Low-income children participating in WIC are just as likely to be immunized as more affluent children and are more likely to receive preventive medical care than other low-income children.

- Children whose mothers participated in WIC while pregnant scored higher on assessments of mental development at age 2 than similar children whose mothers did not participate, and they later performed better on reading assessments while in school.

WIC reaches more than 40 percent of all babies born in the United States, yet a substantial portion of eligible individuals do not participate and thus miss out on its short- and long-term benefits. This reflects two related issues: first, participation tends to be highest among infants and then declines as babies become toddlers and preschoolers; second, participation among eligible individuals overall has fallen in recent years. By reaching more eligible families and making it easier for them to remain in the program longer, WIC could increase its impact on low-income families’ nutrition and health.

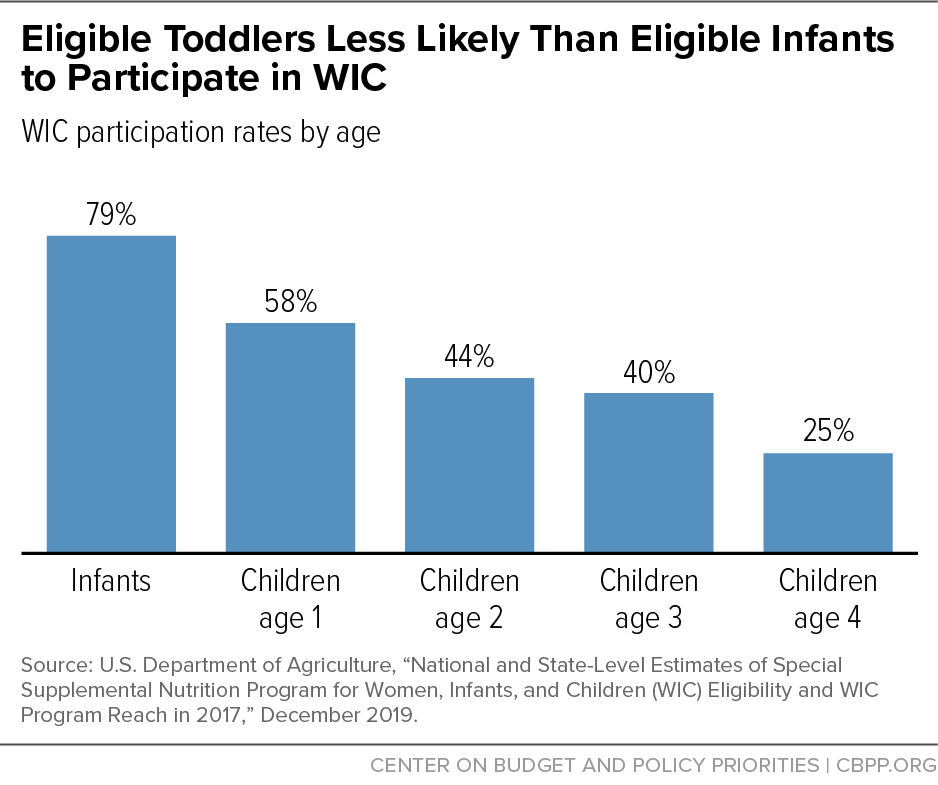

WIC reaches 79 percent of eligible infants, but participation tapers off for eligible toddlers, even though adequate nutrition is critical during the early years of brain development. While WIC participation rates vary widely by state, children aged 1 to 5 tend to have the lowest participation rates across the country.[8] (See Figure 1.) Retaining families that participate in WIC when their babies are born is thus critical to increasing the coverage rate for children.

Recent research has highlighted certain indicators that families are more likely to leave WIC. For example, mothers who do not breastfeed and mothers who do not redeem their WIC food benefits are less likely to recertify their children.[9] WIC programs are experimenting with approaches to reaching out to such families to ensure WIC meets their needs and facilitate recertification.[10]

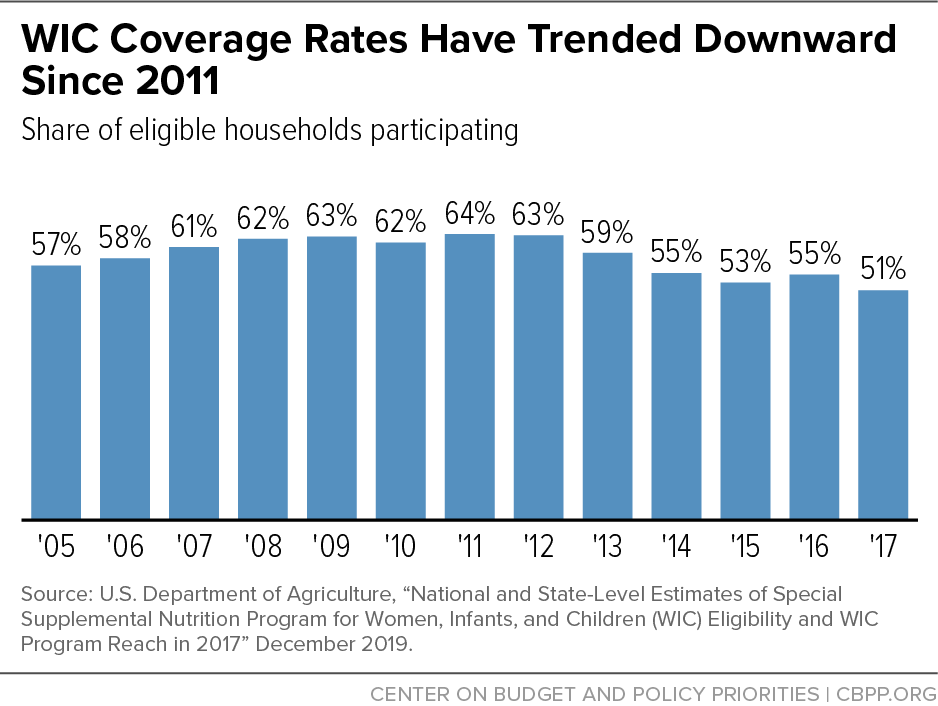

WIC caseloads have fallen across the country in recent years, from a peak of 9.2 million in fiscal year 2010 to 6.4 million in fiscal year 2019. To some degree, this decline is not surprising; it’s appropriate for caseloads to fall as the economy recovers. Also, the number of births has declined in every year since 2007 (except for a modest increase in 2014), with declines concentrated in women under age 30[11] — who are likelier to have low incomes — so fewer pregnant women and young children are potentially income-eligible for WIC. More troubling, however, is that the share of eligible individuals participating in WIC, known as the “coverage rate,” has also fallen.

The coverage rate rose between 2005, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) began regularly developing such estimates, and 2011, peaking at 64 percent.[12] But it fell between 2011 and 2017, to 51 percent, with children consistently having the lowest rate.[13] (See Figure 2.)

In addition to nutritious foods, WIC provides nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and referrals to health care and social services. Providing these services distinguishes WIC from other food assistance programs and is an important focus of WIC staff. Yet it also means that participating in WIC takes more time for low-income families than other means-tested programs. Many families have four or more appointments each year, each of which might require taking time off from work or taking a child out of care. Surveys find three main reasons why some eligible families do not participate in WIC:[14]

- Misinformation. Some families incorrectly believe they are not eligible for WIC. Some common misconceptions are that WIC is not available to families with a working adult or to children once they turn 1 and that it is only available to Medicaid recipients.

- Clinic experience. The perceived value of breastfeeding support, nutrition education, and referrals affects low-income women’s decisions about whether to participate in WIC. The time and effort involved in getting and staying enrolled in WIC also matter. One survey revealed that shorter appointments, the ability to provide documents electronically, and greater flexibility around scheduling and rescheduling appointments (including online scheduling) are important improvements for participating families.[15]

- Shopping experience. The appeal of the specific foods WIC provides and the ease of shopping for WIC foods are important factors in families’ decisions about participating in WIC. Enabling participants to find WIC-authorized stores and WIC-authorized foods more easily and make purchases without stigma or hassle would improve their shopping experience.

While WIC agencies can play a constructive role in addressing all three of the factors listed above, families’ experience in the clinic is most squarely within their control. By allowing families to take care of administrative tasks remotely and receive services remotely when feasible, WIC agencies can reduce the barriers associated with clinic appointments.

Many WIC programs are interested in serving families where they are rather than requiring them to come to WIC clinics, for example by allowing them to complete nutrition education online, locating WIC staff in other settings, conducting WIC appointments during home visits, or using video technology for WIC appointments.

Yet even for appointments in WIC clinics, preparing families for appointments and simplifying certification practices could make it easier for eligible families to enroll in WIC and continue receiving benefits. For example, online appointment scheduling and electronic document submission offer convenience and reduce the length of appointments.

Modernizing and simplifying certification practices does not necessarily reduce interaction between participants and staff. Instead, it can make that interaction more focused, meaningful, and service-oriented. Sometimes streamlining shifts responsibilities from participants to staff, but clinics can still reserve the face-to-face time with participants — and participants’ energy — for WIC services such as breastfeeding support, nutrition counseling, and referrals. And in some cases, modernizing and simplifying certification practices reduces work for staff as well as participants, freeing up time to provide enhanced services.

During 2015 and 2016, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, in cooperation with the National WIC Association, gathered information on WIC practices and procedures to examine how WIC clinics could simplify the processes of applying for and maintaining WIC eligibility. We conducted phone interviews with national WIC experts and state and/or local WIC staff in ten states and site visits to two WIC clinics in each of five states. We also held a workshop with WIC staff from across the country to solicit feedback on our initial findings, and we reviewed selected certification-related policies in state manuals. We found that certification streamlining practices are widespread but far from universal.

Our report summarizing our findings identified five areas that offer opportunities for streamlining or simplification: 1) WIC clinic processes; 2) communication with applicants and participants; 3) policy flexibility; 4) data and reports; and 5) collaboration and outreach.[16] The report, designed to serve as a guide for state and local WIC staff wishing to assess their policies and practices regarding eligibility determinations and enrollment to identify streamlining opportunities, describes specific practices in each area and provides examples from state or local clinics that have implemented them. The practices described are allowable under current federal rules and have been tried by local WIC agencies. The report also summarizes these opportunities in a checklist and includes a summary of the prevalence of selected certification policies by state.

The streamlining practices we observed fall into two broad categories:

- Practices that are quite widespread but have not been universally adopted. Examples include providing automatic calls or texts to remind families about upcoming appointments and accepting documents that can be viewed on a smartphone or computer rather than requiring families to bring paper copies to appointments. If all local WIC agencies adopted these tested practices, certification would be simplified for many participants.

- Policies that are more innovative and less common. Examples include allowing families to schedule appointments online and offering video appointments. As more state and local agencies adopt these practices, participants will experience WIC as a more modern and efficient program.

To promote the streamlining practices described in our report and document examples of implementation strategies, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities hired the Altarum Institute to help launch the Streamlining WIC Certification Practices project in mid-2017. Over two phases of the project, 12 streamlining projects were designed, implemented, and assessed over the course of a year. (See Figure 3.)

Over the course of the year, we provided technical assistance and opportunities for peer support through calls, meetings, and site visits. Each participating agency developed a certification streamlining action plan, implemented it over a nine-month period, then assessed the results, typically by comparing baseline and post-implementation information drawn from staff surveys or program data. The agencies received no additional funding to develop, implement, or assess their streamlining measures.

Because most of the agencies that participated in the project’s first phase (mid-2017 to mid-2018) were local and the timeframe was limited, their projects generally focused on measures that could be implemented quickly, without changing state policy or management information systems. Most of the projects implemented practices that are already widespread; for example, several projects included increasing smartphone use to view documents electronically. Other projects included more unusual practices, such as allowing online appointment scheduling, allowing applicants to provide documents electronically before or after appointments, and checking adjunctive eligibility prior to the certification appointment.

The project’s second phase, which ran over the course of 2019, supported four state WIC agencies that sought to develop a more innovative practice. Each agency selected a local agency partner to help develop and test the practice, with the goal of eventually implementing it statewide. California and Minnesota explored conducting certain appointments by video; Iowa expanded a program developed in one local agency to conduct certifications outside of WIC clinics; and Vermont explored conducting mid-certification appointments by phone.

This report includes detailed case studies of the 12 certification streamlining projects.[17] All of the participating agencies implemented their projects, making adjustments as needed, within the project’s year-long period. Also, all were able to measure the results. For example:

- When Maricopa County, Arizona, started its project, 26 percent of certifications were temporary because clients had not provided all required documents.[18] By training staff to view and receive documents electronically, the agency lowered that figure to 2 percent.

- Greater Baden Medical Services in Maryland reduced the duration of certification appointments by using a mobile app to collect information and documents before appointments.

- Community Medical Centers WIC program in California found that food benefits were issued at a higher rate (4.5 percent per month higher, on average) among participants offered video appointments than among families not offered video appointments, indicating the potential of this approach to increase participation and retention.

- Vermont found that in the pilot, 80 percent of scheduled phone appointments were kept, compared to about half of the in-person appointments.

A survey of WIC participants across the agencies participating in the first phase found that participants rated most aspects of their WIC experience very positively, including the ability to make appointments and provide eligibility documents electronically. One-third (34 percent) indicated that their most recent certification appointment was shorter than in the past; however, fewer were aware that they could provide electronic documents (29 percent) or that other options were available if they lacked necessary documents during the certification appointment.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, enacted in March 2020, allows states to apply for temporary waivers to offer WIC services remotely. All states quickly identified mechanisms for accepting documents electronically and offering telephone appointments.[19] The waivers included flexibility to defer collecting the height, weight, and bloodwork information usually gathered during certification appointments. When states return to operating without waivers, they will be able to retain streamlining measures adopted during the pandemic that are allowed under regular program rules, such as offering options to provide documents electronically before, during, or after appointments. But they will need to adapt their approach to telephone or video appointments. For example, states could offer telephone or video appointments to participants who are exempted from the requirement to attend an appointment in person and could develop protocols for obtaining the necessary health information. The pilots described in these case studies offer a roadmap for how to offer these modernizations under regular program rules.

Within current federal rules, states have flexibility to adopt certain policies that make it easier for families to apply for or continue receiving WIC benefits.[20] State WIC agencies can allow or require local agencies to, for example:

- Certify breastfeeding women and children for up to a year rather than six months.

- Temporarily certify an applicant who doesn’t have all her documents at her certification appointment.

- Accept a document that can be viewed in a photograph or on the internet rather than requiring a printed paper document.

- Exempt infants and children from attending appointments under certain circumstances.

- Offer evening or weekend hours.

- Use an online or automated telephone system to check whether an applicant receives SNAP, Medicaid, or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families cash assistance (TANF) and is thus adjunctively income-eligible for WIC.

Some federal policies, however, create confusion or barriers to access and simplification. USDA or Congress could clarify or change these policies to facilitate enrollment of eligible families. For example, aligning the certification periods of multiple WIC participants in a household can prove difficult or impossible, as participants may have certification periods of different durations or may have begun receiving benefits at different times. Allowing WIC staff to align certification periods and appointments would reduce the number of WIC appointments families must attend.

Streamlining the process of enrolling and remaining in WIC makes it easier for eligible low-income families to participate and benefit from the positive nutrition, health, and developmental outcomes associated with WIC participation. While we do not yet know the extent to which streamlining can change the decline in participation by eligible families, participants respond very positively to WIC agencies’ simplification and modernization initiatives. The case studies in this report offer examples of steps that agencies can take within a year and without additional funding to streamline their certification policies and practices.

The following case studies describe certification streamlining projects undertaken by 12 state or local WIC programs: