- Home

- Issue Brief: Most Working-Age SNAP Parti...

Issue Brief: Most Working-Age SNAP Participants Work, But Often in Unstable Jobs

SNAP (formerly known as the Food Stamp Program) helps millions of Americans put food on the table each month. SNAP helps workers, both to supplement low wages and support them when they are between jobs.While two-thirds of participants are children, elderly, and people with disabilities, who are not expected to work, SNAP also helps workers, both to supplement low wages and support them when they are between jobs, our new analysis finds.[1]

Millions of workers are in jobs that provide low pay, can have shifting schedules, and often lack key benefits such as paid sick leave. These features can contribute to income volatility and job turnover: low-wage workers, including many who participate in SNAP, are more likely than other workers to experience periods when they are out of work or when their monthly earnings drop, at least temporarily. These dynamics lead many adults to participate in SNAP temporarily, often while between jobs or when their work hours are cut. Others, such as workers with steady, but low-paying, jobs, or those unable to work, participate on a longer-term basis. SNAP’s dual function as both a short-term support to help families afford food during a temporary period of low income and a support for others with longer-term needs is one of its principal strengths.

The backdrop of frequent job turnover among low-income workers can make it difficult to assess and quantify the work experiences of SNAP recipients. Looking at work status among SNAP participants at a given point in time substantially overstates their joblessness, as many participants receive SNAP for short-term periods and work both before and after (or work in some months while on SNAP but are underemployed in other months). When data on SNAP participants’ work patterns and low-wage workers’ participation in SNAP are examined over a period of several years, it becomes clear that workers earning low wages are frequently in and out of work and on and off SNAP as their earnings fall and rise. Most low-income, non-disabled adults work, but often with interruptions, and they are more likely to participate in SNAP when they are not working. For the small share of participants who are unable to work or face barriers to work, SNAP is a crucial support that helps them buy groceries.

SNAP Supplements Low Wages and Helps Bridge Gap Between Jobs

We conducted two analyses of work and SNAP participation among adults not receiving disability benefits.[2] First, we looked at participants who received SNAP in a specific month in mid-2012, and we observed their work the year before and after that month (without regard to whether they participated in SNAP in the other months). Second, we looked at the group of non-disabled adults who received SNAP at any point in a roughly 3.5-year period from mid-2009 through mid-2013. Our analysis found:

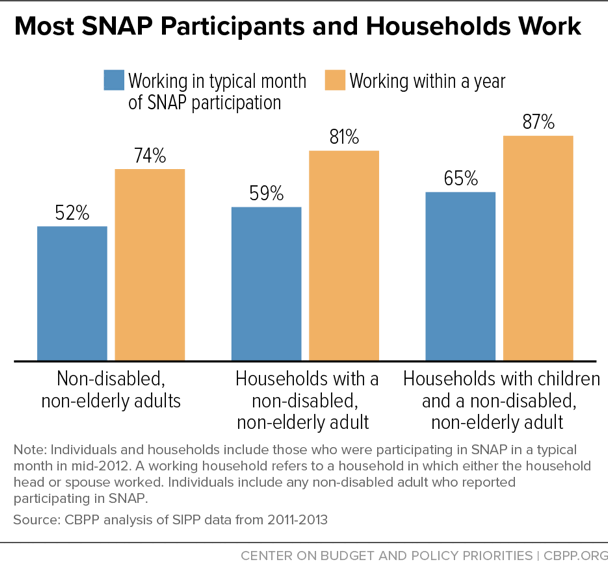

- Nearly three-quarters of adults who participate in SNAP in a typical month work either that month or within a year of that month. Over half of individuals who were participating in SNAP in a typical month in mid-2012 were working in that month. Furthermore, 74 percent worked in the year before or after that month. Work rates were even higher when counting work among other household members. (See Figure 1.)

- Among participants who are employed, work is substantial. When participants work, they typically work at least half time (at least 20 hours per week), and usually full time (at least 35 hours per week). Of those non-disabled adults who participated in a given month in 2012 and worked in the year after that month, about half (52 percent) worked at least six months full time, and an additional 19 percent worked at least one month full time.[3] Some 14 percent did not work full time in that year, but did work half time for at least six months. Only 15 percent worked 20 hours per week for less than six months or worked fewer hours than that for any length of time.

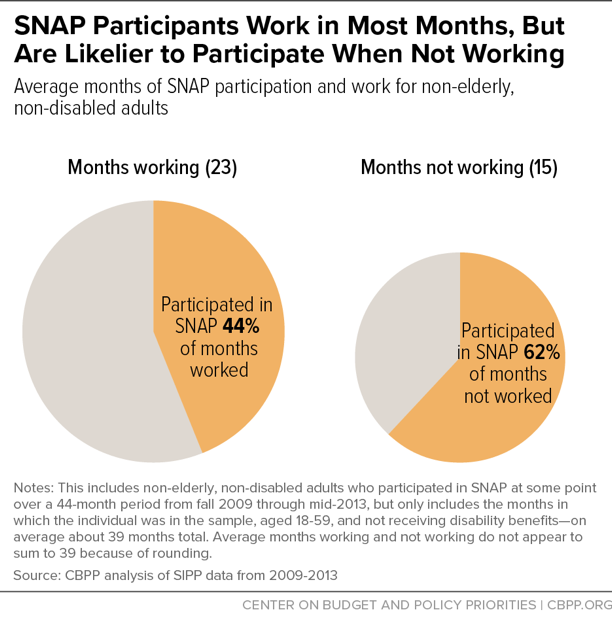

- SNAP participants often experience periods of joblessness and are more likely to participate in SNAP when they are out of work. Individuals who participated in SNAP at any point over the 3.5-year period we studied worked most months in that time, but they were more likely to participate when they were out of work. They participated in SNAP in 44 percent of the months that they were working, and in 62 percent of the months in which they were not working, when they needed more help affording food. (See Figure 2.)

- Non-disabled adults often participate in SNAP for a short time, but those who receive SNAP for longer periods still work most of the time. Nearly two-thirds (64 percent) of the adults who participated in SNAP at some point over the roughly 3.5-year period received it for a total of less than two years. But regardless of how long these adults participated in SNAP, they worked most months in which they received SNAP: those who participated for one year or less worked about 53 percent of the months they participated in SNAP, compared to about 51 percent for both those who participated one to two years and 52 percent for those who participated more than two years. Over one-third of non-disabled adults worked in every month they participated in SNAP.

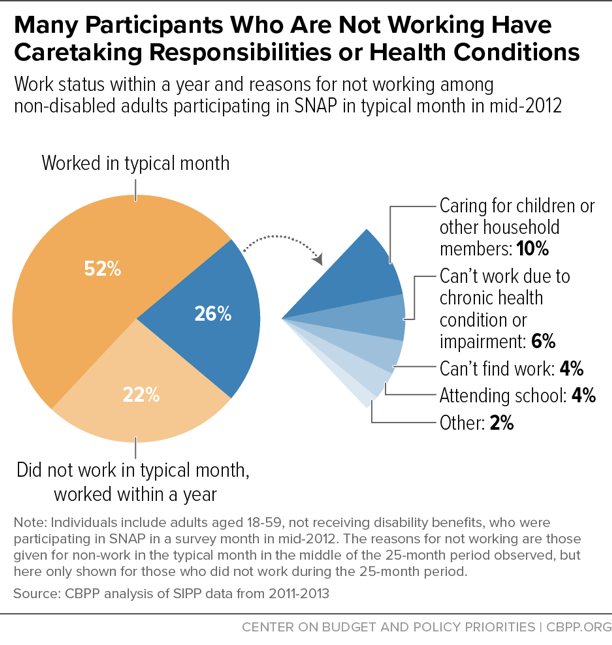

- SNAP participants who are consistently out of work often face barriers to work or have caretaking responsibilities. About one-quarter of adults who participated in SNAP in a given month in 2012 did not work within a year. Of those adults, most cited caretaking responsibilities or health conditions as the reasons they were not working. (See Figure 3.)

Harsher Work Rules Won’t Boost Work, Will Hurt Those Who Need SNAP

Existing policy already limits SNAP participation for childless adults under age 50 who are not employed at least half time to just three months out of every three years, and imposes other work requirements, for which failure to comply can result in sanctions. Policies that would further limit SNAP for jobless participants would harm many individuals who work and those who face significant obstacles to employment. For individuals who earn persistently low wages, putting up additional barriers to receiving SNAP will not improve their labor market prospects. For those who are out of work for longer periods, helping them increase their ability to work in a meaningful way would require an investment in resources, rather than a denial of basic food assistance.

Results from other programs show that work requirements rarely lead to significant increases in meaningful employment, and often result in increased poverty for those who lose benefits without increasing earnings. The most successful interventions offer intensive assessment and training and supportive services, which are extremely expensive, and are provided for voluntary participants. In addition, Congress provided funding in 2014 for ten comprehensive SNAP employment and training demonstration projects to test whether new, innovative approaches would help boost employment and earnings. Policymakers should wait to learn the results from these demonstrations before instituting policies that research indicates won’t likely significantly increase work — but will make it harder for families to put food on the table.

End Notes

[1] For our full analysis, including a discussion of our methodology, see Brynne Keith-Jennings and Raheem Chaudhry, “Most Working-Age SNAP Participants Work, But Often in Unstable Jobs,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 15, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/most-working-age-snap-participants-work-but-often-in-unstable-jobs.

[2] We refer to these adults as “non-disabled,” but given the strict requirements and lengthy application process to qualify for and receive disability payments, many of these individuals may have health conditions or other impairments that could be considered disabilities.

[3] We limited this analysis to the two-thirds of all non-disabled adults who received SNAP in a given month in mid-2012 who worked in the year after that month, because considering work over a one-year period is more intuitive than looking at work over a 25-month period. While we chose those who worked in the year after the given month, findings are very similar when looking at work among those who worked in the year before the given month.

More from the Authors