- Home

- Working Families Tax Relief Act Would He...

Working Families Tax Relief Act Would Help 46 Million Households, Cut Poverty and Deep Poverty

The Working Families Tax Relief Act, introduced in the Senate by Sherrod Brown, Michael Bennet, Richard Durbin, and Ron Wyden (S. 1138) and in the House by Dan Kildee and Dwight Evans (H.R. 3157), would substantially expand the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC), improving the economic well-being of 46 million households. These credits reward work, reduce poverty, and improve children’s opportunities, but they can do substantially more. The bill’s EITC and CTC expansions would lift 29 million people above or closer to the poverty line, including 11 million children, reducing the poverty rate from 14 to 12 percent, the child poverty rate from 15 to 11 percent (a 28 percent decline), and the child deep poverty rate from 5 percent to 3 percent (a 40 percent decline). (These figures use the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which counts refundable tax credits as income.) And, in combination with legislation to raise the minimum wage and provide paid family and medical leave, the bill would help address the income stagnation that has affected working-class Americans across racial and ethnic lines.

Tax Credit Expansions Would Sharply Reduce Deep Poverty Among Children

The Working Families Tax Relief Act would expand the EITC for families with children by roughly 25 percent. It also would substantially strengthen the very small EITC for working people who aren’t raising children in their home — the sole group that the federal tax code now taxes into, or deeper into, poverty. The EITC expansions alone would benefit an estimated 75 million people in 35 million households.

The bill also would make the CTC fully refundable so that children in low-income households, including those with little or no income, can benefit from it. Today, the CTC either leaves out or provides only a small, partial credit to millions of the children and families with low incomes — the people who need it most. Indeed, the 2017 tax law’s $1,000-per-child CTC increase largely bypassed 26 million children in low- and moderate-income working families.

In addition, the bill would create a fully refundable Young Child Tax Credit for children under age 6. Research shows that this is a period of great importance and vulnerability in children’s lives, and that more adequate family income in these years can improve poor children’s opportunities. The Young Child Tax Credit would raise these families’ child credit to $3,000 per child. The bill’s CTC changes as a whole would benefit an estimated 43 million children, lifting 10 million children above or closer to the poverty line. Of particular note, it would dramatically reduce deep poverty among children (that is, children who live below half of the poverty line), lifting 1.3 million children out of deep poverty and reducing the deep poverty rate among children by 37 percent (from 5 percent to 3 percent).

Taking its EITC and CTC expansions together, the Working Families Tax Relief Act would boost the after-tax incomes of an estimated 114 million people in 46 million households, including 24 million white families, 9 million Latino families, 8 million Black families, and 2 million Asian American families.

These examples illustrate the bill’s impact:

- A mother of a 4-year-old and a 7-year-old works as a home health aide making $20,000. The bill would raise her CTC by $2,210 and her EITC by about $1,460, for a combined gain of about $3,670.

- One partner in a married couple makes $45,000 as an auto mechanic, while the other takes care of their two young children full time. The bill would increase their EITC by about $1,460, and they’d receive an additional $2,000 from the Young Child Tax Credit, for a combined gain of about $3,460.

- A fast-food cook working full time at the federal minimum wage earns $14,500, or slightly above the poverty line for a single individual. But she must pay over $1,250 in combined federal individual and payroll taxes, so the tax code actually pushes her below the poverty line. The bill would increase her EITC by about $1,530. She’d no longer be taxed into poverty.

Over the next two years, policymakers are expected to debate numerous proposals to boost struggling families’ incomes, including minimum wage increases, more vigorous anti-trust enforcement, and other ways to restore bargaining power to rank-and-file workers. The Working Families Tax Relief Act’s tax-credit expansions would complement such efforts by providing substantial wage supplements to many families and should be a policy priority. Both types of policies are needed to address the powerful economic barriers that many families face.

Working-Class Incomes Have Stagnated

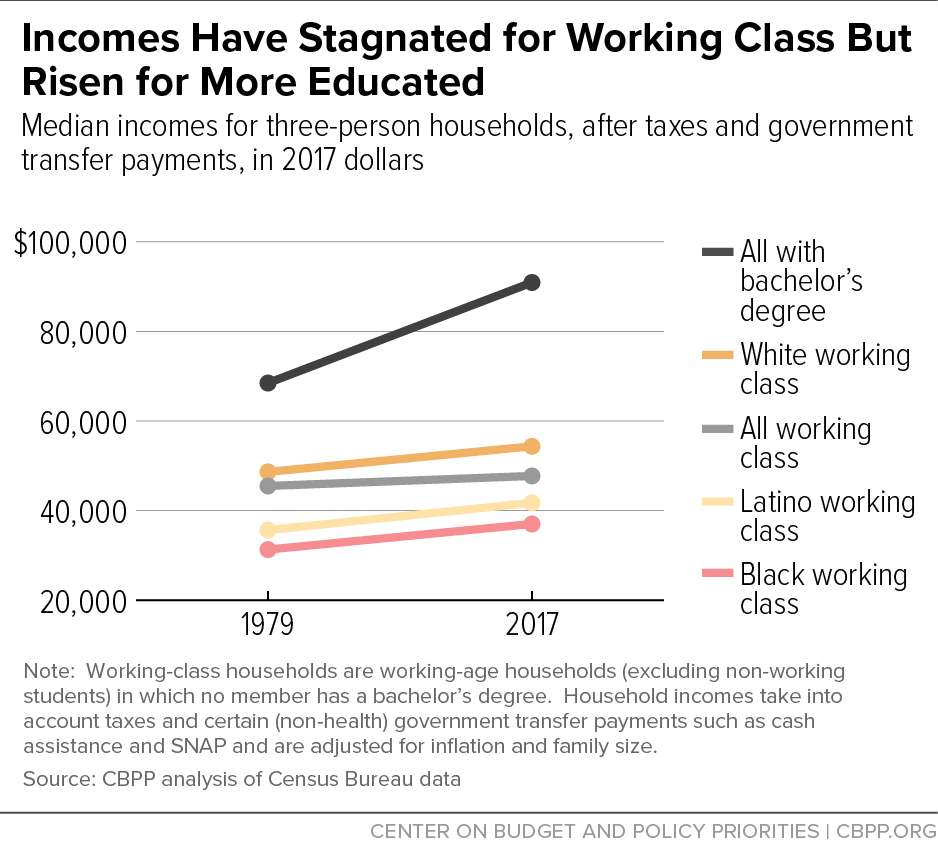

The median income for working-class households (a term we use to refer to working-age households where nobody has a bachelor’s degree) grew just 5 percent over the 38 years from 1979 and 2017, after adjusting for inflation and accounting for taxes and certain government transfer payments (such as SNAP and cash assistance). By contrast, households at the top enjoyed very rapid income growth over this period, while median incomes for households with a bachelor’s degree rose 33 percent. (See first chart.) The main driver of income stagnation among working-class households is the decline in their real hourly wages. Working-class households managed to mostly maintain their incomes over this period, despite falling wages, in part by working more.

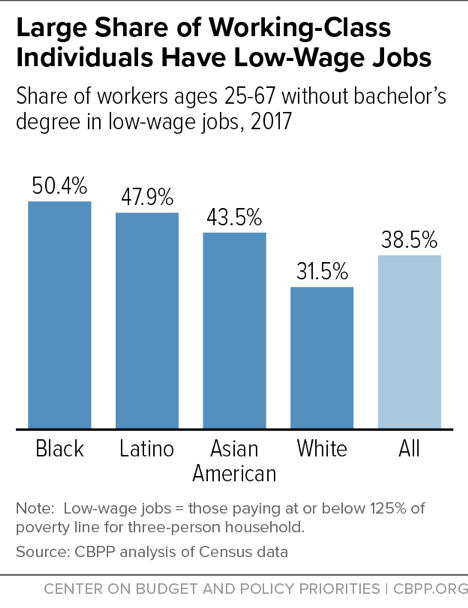

Roughly 40 percent of employed working-class Americans work in low-wage jobs (those with hourly wages too low for a full-time, full-year worker to keep a family of three above 125 percent of the poverty line). Low wages affect a large share of working-class workers of every race, but the problem is especially acute in communities of color: about half of Black and Latino workers without a bachelor’s degree were in low-wage jobs in 2017. (See second chart.)

The high prevalence of low-wage jobs among working-class Americans will likely persist, as most of the occupations not requiring a bachelor’s degree that are projected to add the most jobs over the next decade pay low wages. A strong EITC, along with strengthened labor-market policies, will likely be essential to ensuring that these workers can support their families.

Proposal’s Highlights

The Working Families Tax Relief Act would:

- Raise, by roughly 25 percent, both the rate at which the EITC for families with children phases in and the maximum credit. That would increase the maximum EITC by about $880 for families with one child, $1,460 for families with two children, and $1,090 for families with three or more children.

- Substantially increase the EITC for workers not raising dependent children. The bill would raise the maximum EITC for childless workers from roughly $530 to $2,070 and raise the income limit to qualify for the credit from about $16,000 for a single individual to $25,000. It would also expand the age range of workers eligible for the credit from 25-64 to 19-67.

- Make the $2,000 CTC fully refundable and create a $3,000 Young Child Tax Credit that adds $1,000 to a family’s CTC and is also fully refundable. Both credits would be adjusted for inflation.

- Provide a federal match for Puerto Rico’s new EITC to help reduce the Commonwealth’s high child poverty rate and raise its low labor-force participation rate.